- to define public health and distinguish between public health and individual health care;

- to identify how public health is measured or diagnosed;

- to identify types of public health intervention.

Introduction

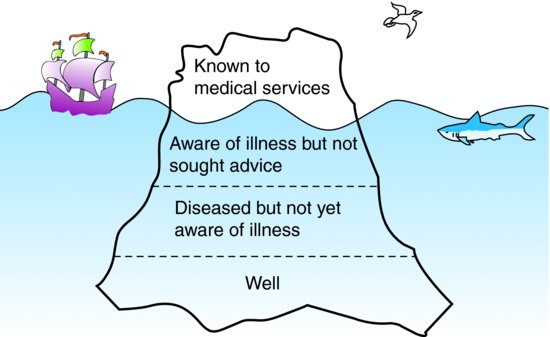

Public health has been defined as: ‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through organised efforts of society’. Public health focuses on improving the health of entire populations rather than on individual patients. The population is the patient. Tools for improving population health range from the development of new clinical services for treating disease, screening programmes to detect disease at an early (treatable) stage, immunisation to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases, to legislation to prohibit actions or behaviours, or health improvement in schools and workplaces. Public health aims to encompass the whole clinical iceberg (see Figure 15.1).

Public health seeks to target all ill health comprising the population that are asymptomatic or prodromal (unaware of illness), the population that have not yet presented to medical services as well as population being managed by health care services.

Public health practice

Public health is an interdisciplinary practice – with public health specialists operating locally, nationally and internationally; within healthcare services, local authorities, the voluntary sector and other government bodies – and drawing on a multitude of skills. As we write this chapter UK public health along with the NHS is being reorganised. This is not new – and however public health is organised the type of problems specialists tackle and the approach they take will be similar. What is common and critical is the population approach, i.e. that health needs are identified and assessed and interventions delivered and evaluated at a population level.

The three domains of public health in the UK are:

| Health improvement | Improving services | Health protection |

| Inequalities | Clinical effectiveness | Infectious diseases |

| Education | Efficiency | Chemicals and poisons |

| Housing | Service planning | Radiation |

| Employment | Audit and evaluation | Emergency response |

| Family/community | Clinical governance | Environmental health hazards |

| Lifestyles | Equity | |

| Surveillance and monitoring of specific diseases and risk factors |

Many of these are covered elsewhere in the book – including infectious disease epidemiology and health protection; and evidence based medicine which underpins improving services. The issues in health improvement emphasise that public health aims to reduce inequalities as well as improve population health and that public health interventions can operate at multiple levels. As well as the domains above, public health is concerned with Health Impact Assessment (HIA) – UK and international examples of which are collated at the HIA Gateway. HIA is defined by WHO as ‘A combination of procedures, methods and tools by which a policy, programme or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of a population, and the distribution of those effects within the population’.

The United States Communicable Disease Control has identified ten public health achievements of the twentieth century (Figure 15.2).

Figure 15.2 The twentieth century’s ten great public health achievements (in developed countries).

Source: http://www.cdc.gov.

It is estimated that the average lifespan in the US increased by >30 years during the twentieth century and that 25 years (~3/4) of the gain is attributable to public health. Similar gains have occurred in other industrial/developed countries. The contribution of public health interventions include: eradication of smallpox, elimination of polio, and control of many other infections through ‘vaccination’; reductions in motor vehicle accidents due to improvements in driving and ‘motor-vehicle safety’; reductions in environmental exposure and occupational injury through ensuring ‘safer work places’; improved sanitation, availability of clean water, and antimicrobials leading to better ‘control of infectious diseases’; reductions in risk behaviours, such as smoking, and control of blood pressure and early detection have contributed to a decline in ‘deaths from coronary heart disease and stroke’; better hygiene and nutrition of mothers and babies has contributed to reductions in neonatal and maternal mortality; and the many anti-smoking campaigns and policies have led to changes in public perceptions of the dangers and acceptability of smoking by the public and substantial reductions in smoking and environmental exposure to tobacco in the population. Morbidity and socioeconomic circumstances also have improved through ‘safer and healthier foods’ reducing frequency of diseases associated with nutritional deficiency (such as rickets and pellagra); family planning/contraceptive services reducing family size and transmission of sexually transmitted infections; and fluoridation has made substantial reductions in tooth decay and loss.

These represent a range of different interventions:

- primary prevention: such as vaccination and health promotion campaigns; legislation and enforcement to promote safer driving, and safer work places;

- environmental and social changes: including improved nutrition and availability of clean water and fluoridated water;

- medical advances: such as hygiene during child birth and other surgical interventions; and more aggressive identification and treatment of early signs of heart disease.

The health problems affecting low and middle income countries differ from those of industrialised nations – and some of the public health achievements of the twentieth century identified above are as yet unresolved in developing countries. For example, there were approximately 6.5 million deaths in children under five in African and Southeast Asian countries in 2008 (Black et al., ). The top six causes were: pneumonia (18%); diarrhoea (15%); neonatal birth complications (12%); neonatal asphyxia (9%) or sepsis (6%) and malaria (8%). Key interventions to prevent these deaths include: clean/sterile delivery, nutrition and nutritional deficiencies (e.g. vitamin A and zinc), antibiotics, water sanitation, vaccination (Hib and measles), oral rehydration, and mosquito (insecticide treated) nets. Key public health interventions in developed and developing countries can be medical, educational, social or legal.

Public health diagnosis

The steps to improving public health are analogous to clinical medicine but with slightly different tools. We need to ‘diagnose’ the problem. The tools at our disposal are information on the population, routine data on mortality and morbidity, hospitalisation, public health surveillance data, population health surveys and other epidemiological studies. Some of the key sources used in the UK are listed below. These allow us to measure rates of disease in the population, and consider variations in health and disease in different populations and over time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree