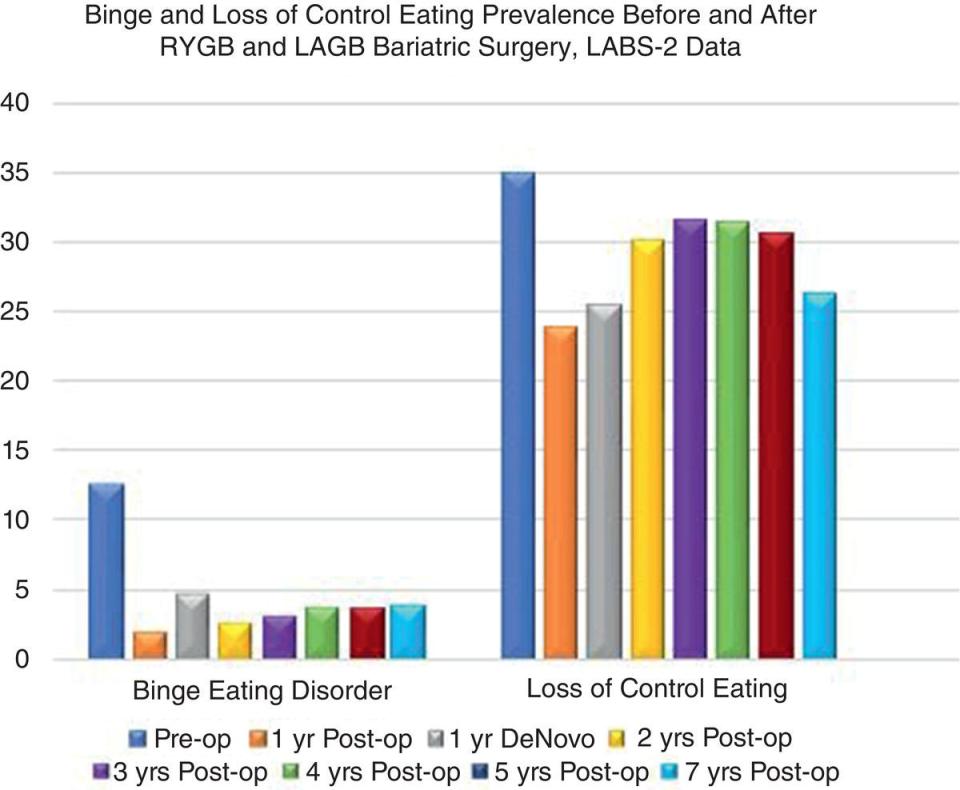

Paul Davidson For the bariatric surgeon, chief concerns following bariatric surgery tend to focus on medical issues and possible complications from the procedure. From the patient perspective, psychological issues tend to be a more central area of attention provided there are no serious medical problems, and a number of these may present only post‐operatively. In addition to ongoing medical/surgical and nutritional care, behavioural follow‐up can play a crucial role in the long‐term experience of the bariatric patient. A comprehensive psychosocial–behavioural evaluation conducted by a licensed behavioural health specialist versed in the field of obesity, eating pathology and bariatric surgery is part of the guidelines of bariatric surgery. However, only support groups are considered a mandatory offering for post‐operative emotional care. Success following bariatric surgery is highly dependent on a triad of medical, nutritional and psychological changes that are supported by interdisciplinary treatment from each discipline. The desire to be approved for surgery may lead individuals to minimise their emotional problems upon initial evaluations, particularly in front of surgeons. A review of post‐operative psychological issues should bring greater appreciation to those in the field of the value of addressing these concerns as expediently as possible to minimise their negative impacts. Such interventions have been shown to lead to improved weight‐loss outcomes in meta‐analytic evaluation of the literature. Various forms of pathological eating may exist prior to bariatric surgery, and these may have a negative impact on bariatric success and excess weight lost. Importantly, problematic eating behaviours tend to decrease post‐operatively, though others may recur or arise following surgery. The most common form of disordered eating involves binge eating, the consumption of an excessively large amount of food in a limited time in which there is a sense of a loss of control followed by feelings of guilt or shame. This may be present in up to 12.7% of individuals seeking bariatric procedures. The loss of control element of disordered eating seems to have a much higher prevalence at 35% of pre‐surgical patients. Over time, there appears to be a clear decrease in these habits, especially binge eating, but a fair degree of loss of control eating tends to persist at seven years post‐operatively, as shown in Figure 26.1. While there has been speculation that pre‐operative problematic eating behaviours may impair weight‐loss outcomes, research suggests that it is actually the presence of these behaviours post‐operatively, which have the greatest impact on weight recurrence. Additionally, de novo cases are reported within a year following surgery, as does the common habit of grazing, which consists of picking at or nibbling at food. In each case, cognitive behaviour therapy has proven to be the treatment of choice and may be aided by the addition of psychopharmacology. Figure 26.1 Binge and loss of control eating prevalence before and after RYGB and LAGB bariatric surgery, LABS‐2 data Source: Based on Smith et al. (2019). Both emotional eating and uncontrolled eating behaviours have been found to decrease the percent of excess weight lost by gastric bypass patients, regardless of how long someone had been post‐operative. Patients who felt less disinhibition and more hunger one year after surgery had poorer results 10 years post‐operatively in one long‐term study. Those experiencing poorer control of eating habits are likely to benefit from closer and more frequent behavioural follow‐up post‐operatively. After surgery, binge eating may take the form of subjective loss of control, distress, regrets after eating, and a more rapid pace of eating, as it may no longer be possible to consume an objectively large amount of food. Once again, cognitive‐behavioural treatment is preferred. Grazing, the habit of picking at or nibbling on food over an extended period of time, was not only related to less weight loss, but also correlated with greater emotional distress. These conditions were deemed to be clear indications for post‐operative behavioural interventions. It is estimated that 30–43% of bariatric patients show signs of this following surgery. Treatment for problematic and disordered eating should begin as early as possible in the post‐operative period as soon as disordered eating patterns occur. Self‐monitoring is an appropriate start using food logs, regular weighing, and activity trackers. The next stage would be to then engage in psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacologic approaches as the situation requires. Technology such as smartphone apps and online resources for behavioural skills tend to have high rates of patient engagement and may be of significant treatment assistance. The use of cognitive–behavioural strategies prove most useful in both individual and group settings. Offering motivational skill building as well as psychopharmacology have also been shown to be useful adjuncts in the care of bariatric patients experiencing post‐operative psychological conditions manifesting as eating issues. It is also valuable to engage familial support when possible as this has been shown to decrease grazing behaviour and weight recurrence. Encouraging behavioural treatment that involves family and support members may help decrease post‐surgical problematic eating issues. Patient surveys have shown increased interest in post‐operative care to deal with problematic eating and accompanying weight gain. For many, there is a desire for monthly treatment groups in which they can interact with other patients experiencing similar issues. For those attending bariatric support groups, increased satisfaction, greater programme engagement and improved weight loss have been noted, which is why they are recommended as a part of each patient’s post‐operative care. Individuals who do not follow‐up on a regular basis with their programme have been shown to have poorer weight loss and more weight recurrence. While in person treatment is preferred, the availability of telehealth options can enhance engagement in treatment and may be preferable when there are issues of distance from care or other intervening factors that make in person care improbable. There is a higher incidence of psychiatric conditions amongst individuals seeking bariatric surgery, both in terms of lifetime prevalence and meeting criterion upon initial assessment. Reviews have shown a range of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis from 36.8 to 72.6%, within the bariatric population, significantly higher than what is seen in the general population. At the time of initial evaluation, roughly 55% are diagnosed with some form of psychiatric disorder. The majority of these consist of mood disorders, found in nearly 30% of those presenting for bariatric surgery. While a substance use history was found in up to a third of bariatric patients, at the time of initial evaluation, it was documented in only 2% of the cases. The presence of a current eating disorder was noted in 17% of those undergoing behavioural evaluations, again a number greater than would be observed in the general population. These findings are presented in Figure 26.2. Figure 26.2 Prevalence percentage of preoperative psychiatric issues. Source: Based on Sarwer et al. (2019) and Dawes et al. (2016). Given the increased prevalence of varying psychiatric issues amongst bariatric patients, it has highlighted the need for post‐operative behavioural treatment. The typical course of depression following bariatric surgery has been a general decrease in symptomatology, particularly within the first few years. For those with depression, a motivationally focused behavioural treatment, both pre‐ and post‐surgery, proved to be superior to treatment as usual, and pre‐operative cognitive behavioural therapy has been shown to lessen anxiety post‐operatively. However, anxiety disorders tend to be more persistent following surgery than mood disorders. With both depression and anxiety disorders, psychopharmacology may be indicated for more severe symptom improvement. Despite general improvements in psychosocial functioning post‐operatively, there are pernicious factors that can lead to psychological concerns. Negative self‐esteem and poor body image along with internalised weight bias are factors that have been linked to potential issues following surgery. In a study of gastric bypass patients, these emotional factors were predictive of psychological issues after surgery. Though typically a sign of excellent weight loss, excess skin can add to dissatisfaction with bariatric results and have a negative effect on both self‐image and intimate relationships. Individuals may address these feelings through psychotherapy, but a subset find greatly improved physical and social satisfaction after body contouring surgery.

26

Psychological Considerations Post‐Surgery

Disordered Eating and Weight Recurrence

Psychiatric Co‐Morbidity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree