TREATMENT

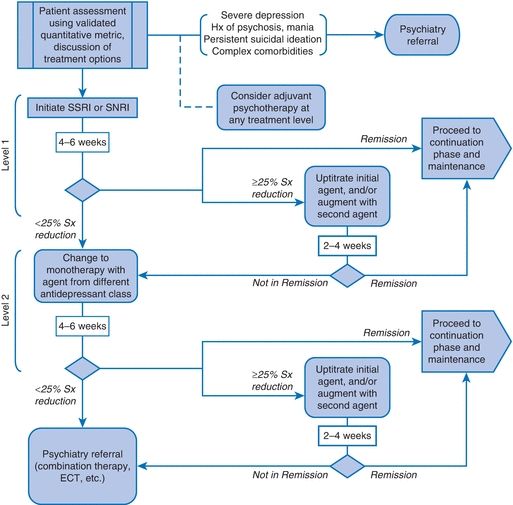

- Depression treatment consists of three phases15,16:

- Acute therapy (usually 6 to 12 weeks)

- Continuation (4 to 9 months), which targets prevention of relapse

- Maintenance (6 months to years), which targets prevention of a new distinct episode of major depression

- Acute therapy (usually 6 to 12 weeks)

- Bipolar and mixed mood syndromes require mood stabilizers (e.g., atypical antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, lithium) before antidepressant treatment to prevent triggering mania.

- Bipolar disorder eventually manifests in up to 10% of patients initially thought to have unipolar depression.

- Strongly consider treatment of patients with low mood who do not strictly meet criteria for depression but exhibit significant functional impairment.

Acute Therapy

- Patients and family members should be educated that

- Depression is a medical illness, not a sign of weak character.

- Depression can be effectively treated.

- Patients improve with treatment.

- Depression can recur, and patients should seek treatment early if symptoms return.8

- Depression is a medical illness, not a sign of weak character.

- Acute therapy should target symptom remission and not merely improvement.8,11,16 Response to treatment is defined as a ≥50% reduction in symptomatology.8

- Depression-specific psychotherapies and antidepressant medications have similar response rates for mild depression. Both are acceptable initial approaches.

- Antidepressants should be started in patients with moderate or severe major depression. Adjuvant psychotherapy may improve response, especially in severe, recurrent, or chronic depression.8,11,16–20

- Depression with psychotic features should be treated with a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic medication and/or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).2

- Patients may require ≥6 weeks to achieve full symptom remission after treatment begins.8,21

- If a patient experiences a symptom reduction of ≥25% 4 to 6 weeks after treatment initiation but is not yet in remission, continue current therapy with medication uptitration if tolerated.8

- If there is <25% reduction of symptoms after 6 weeks of appropriate therapy, either adding or switching to another treatment are both effective.8

- Patients who do not respond to an initial selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) have a modestly better chance of response, if changed to a non-SSRI rather than a different SSRI.8,11,21

- Augmentation may include the addition of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), bupropion, mirtazapine, and/or adjuvant nonpharmacologic interventions. Other strategies may require the assistance of a psychiatrist.

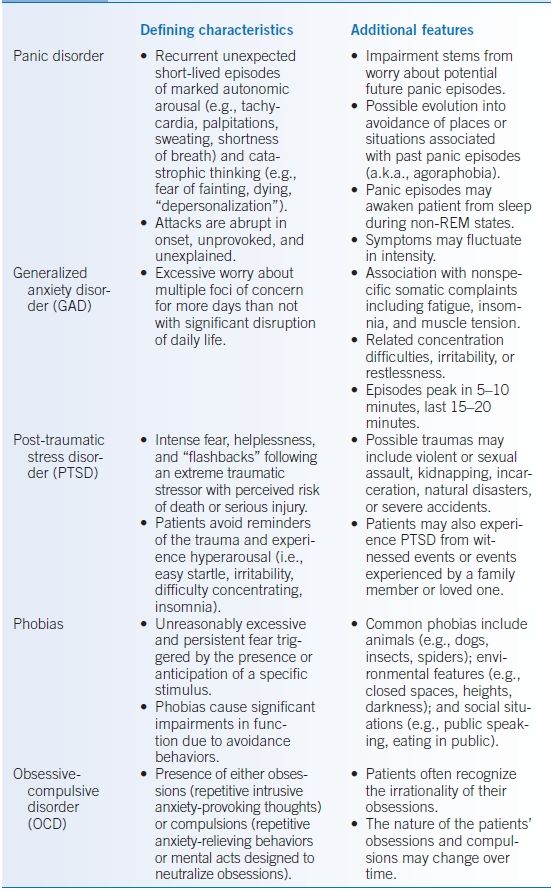

- Figure 42-1 provides a recommended schema for acute treatment with antidepressant medications. Other well-validated algorithms can be used, including the algorithms used in the STAR-D study for depression and the STEP-BD study for bipolar disorder.22–24

- Medications should be tapered when discontinued or added, with vigilance for drug-drug interactions, overlapping side effect profiles, and withdrawal phenomena.

- Patients should be routinely monitored for suicide risk throughout therapy.

Figure 42-1 Suggested schema for acute therapy with antidepressant medications. SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Duration of Treatment

- Treatment should be continued for at least 4 to 9 months after remission of symptoms (the continuation phase).25 Recurrent episodes imply the need for longer medication maintenance.

- First episode: continue medication for 6 to 12 months, withdraw gradually.

- Second episode: continue medication for 3 years, withdraw gradually.

- Three episodes or more: continue medication indefinitely.

- First episode: continue medication for 6 to 12 months, withdraw gradually.

- When antidepressants are discontinued, it is commonly recommended that the medications be tapered over 2 to 4 weeks to minimize withdrawal.8

Medications

- Data suggest minimal difference in efficacy among antidepressants for the acute treatment of depression.26,27

- While data are limited, it appears that most medications are also equally effective in preventing relapse. Side effect profiles and cost considerations should guide treatment choices (see Table 42-2).

- Adherence to medication, even after symptom improvement, is key. Premature discontinuation of antidepressant treatment is associated with a 77% increase in the risk of relapse or symptom recurrence.8

- Risks for premature self-discontinuation include younger age, lower educational status, and higher self-perceived mental health.21

- SSRIs and SNRIs are considered first-line agents given their side effect profiles. There appears to be minimal within-class differences in efficacy.

- TCAs are effective but should be used cautiously given cardiac side effects and risk for lethal overdose. Higher doses of TCAs may be more effective in those who partially respond to lower doses.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) should be restricted to patients unresponsive to other medications because of their potential for drug interactions, serious side effects, and the necessity of dietary restrictions. Psychiatric consultation is strongly recommended if an MAOI is considered.

- Psychostimulants (e.g., dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, and methylamphetamine) are useful adjuvant treatments for depression but have not been adequately studied for use as monotherapy. Psychiatric consultation is strongly recommended if stimulants are considered.

- St. John’s wort and S-adenosyl methionine (SAM-e) are sometimes self-prescribed as natural antidepressants. Studies show mixed results regarding efficacy of these as antidepressants and serious drug-drug interactions as well as the heterogeneity of commercially available preparations argue against use.8,18,28 Other herbals and dietary supplements, such as kava-kava, omega-3 fatty acid (docosahexaenoic acid), and valerian root, have not been proven effective for the treatment of depression.8,28

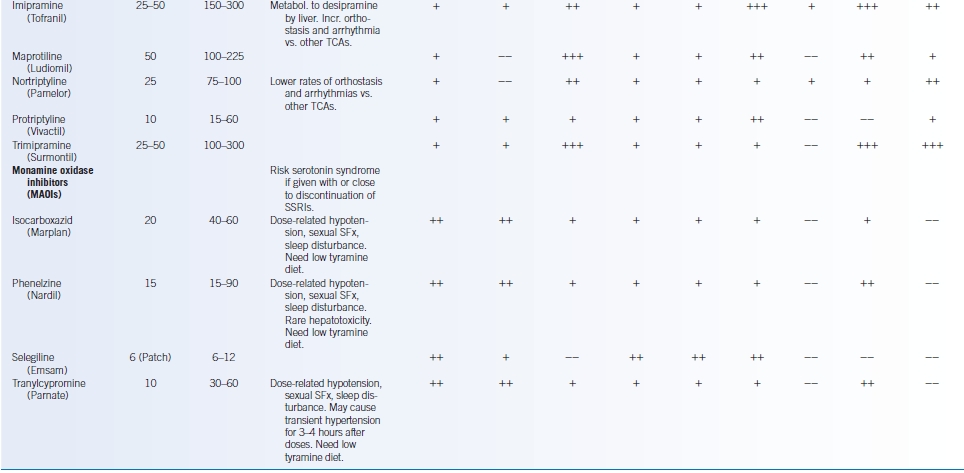

TABLE 42-2 Antidepressant Medications

Contraind., contraindicated; CYP, cytochrome-P450; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; immed., immediate; inhib., inhibition; LDL, low density lipoprotein; metabol., metabolized; MI, myocardial infarction; Rx-Rx interact., drug-drug interaction; signif., significant; SFx, side effects; QTc, corrected QT interval; – -, rare; +, seldom; ++, common; +++, frequent.

Modified from Clinical Pharmacology. 2014. http://www.clinicalpharmacology-ip.com. Last accessed 2/1/15. Depression Guideline Panel. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in Primary Care: Treatment of Major Depression. AHCPR Publication No. 93-0551. Rockville, MD: AHCPR; 1993; Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Thieda P, et al.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparative Effectiveness of Second-Generation Antidepressants in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Adult Depression. AHRQ Publication No. 07-EHC007-EF. Bethesda, MD: AHRQ; 2007.

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

- Several psychotherapy modalities are effective in the treatment of depression.19 Such interventions should be performed by therapists specifically trained in these techniques.

- Combined therapy using both pharmacologic and psychological therapy may be more effective than either intervention alone.8,19

- ECT may benefit patients with refractory depression, depression with psychotic features, and geriatric patients.

- Other neuromodulation techniques (e.g., repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and vagus nerve stimulation) have shown some promise in treating resistant depression but require psychiatric evaluation.

- Depression that is worse in winter (i.e., seasonality) often improves with phototherapy using broad-spectrum bright light (typically 10,000 lux).29 Such therapy should be initiated only by clinicians trained in prescribing phototherapy.

- Aerobic exercise may be of adjuvant benefit in reducing depressive symptoms.8,18,30 Patients should aim for 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise, 3 to 5 days per week.

REFERRAL

- Multiple trials demonstrate the benefit of a collaborative care model with the close integration of physicians, mental health professionals, and case managers.8 While both general medicine and psychiatric specialty settings yield good initial outcomes, therapeutic alliance with mental health specialists should be strongly considered.21

- Psychotherapy should be administered by a skilled therapist. Data suggest that the success of psychotherapy may be linked to the experience level of practitioners.

- Strongly consider psychiatrist or mental health specialist referral if there is intolerance or minimal benefit with first-line agents; signs of psychosis or suicidal ideation; severe symptoms or functional impairment; comorbid medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse disorders; symptoms or history suggestive of mania/bipolar disease or seasonal affective disorder; plans for psychotherapy; need for frequent or close follow-up; and/or patient requests for specialist treatment.

- Consider hospitalization if the patient poses a serious risk for harm to self or others (involuntary hospitalization may be necessary), is severely ill and lacks adequate social supports, has not responded adequately to outpatient treatment, or has significant comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions.16

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

Expert opinion recommends patients should be

- Seen within 2 weeks after starting any medications to evaluate for tolerability, effectiveness, and appropriate dosage

- Followed at least every 2 weeks until significant symptom improvement

- Followed at least every 3 months after symptom remission.25

OUTCOME/PROGNOSIS

- Depression is a heterogeneous disorder with a highly variable course.7

- In most patients, major depression is a relapsing-remitting illness with a >40% risk of recurrence within 2 years after the first depressive episode.14

- Repetitive episodes increase the risk of future recurrence.

- Relapse prevention with pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities diminishes but does not completely prevent relapse.19 Clinicians should be mindful to monitor for depression recurrence.

DELIBERATE SELF-HARM AND SUICIDALITY

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Deliberate self-harm commonly involves self-cutting, self-poisoning, or intentional medication overdose.31

- Suicide is an act of self-harm with a fatal outcome, consciously initiated and performed with the expectation of death.31

- Individual self-harm acts vary in their associated suicidal intent, degree of planning (e.g., meticulous vs. impulsive, precautions against rescue), and lethality of method (e.g., violent vs. passive).

Epidemiology

- About 3% to 5% of the population has made an attempt at deliberate self-harm at some time during their lives.31

- Approximately one quarter of those with one self-harm attempt will reattempt self-harm within 4 years, with a long-term suicide risk of 3% to 7%.5

- The median mortality from suicide after an act of deliberate self-harm is 1.8% within the first year, 3.0% within 1 to 4 years, 3.4% within 5 to 10 years, and 6.7% within 9 years or longer.31

- Younger adults are more likely to attempt nonfatal self-harm, whereas older adults are more likely to complete suicide.

- Women attempt suicide two to three times as often as men, but men are four times as likely to die by suicide.5

- The highest suicide rates in the United States are found in white men >85 years of age.5

- >90% of those who commit suicide suffered from a mental illness, most commonly a mood or a substance abuse disorder.5

Etiology/Pathophysiology

- Evidence suggests that genetic predisposition, biologic changes, and psychosocial factors all contribute to deliberate self-harm.31

- Reduced serotonin function and lowered cerebrospinal 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels in the central nervous system may underpin the pathophysiologic changes of self-harm.

- Patients who deliberately self-harm also show personality traits of impulsiveness, aggression, inflexibility, and impaired judgment.

Risk Factors

- A large number of risk factors have been associated with suicide attempts including the following8,31,32:

- Suicidal thoughts, past attempts, specific/lethal plans, access to firearms

- Psychiatric illness (depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance abuse)

- Psychological features (shame, low self-esteem, impulsiveness, aggression, hopelessness, severe anxiety)

- Significant burden of medical illness

- Socioeconomic factors (lack of support, unemployment, recent stressful events)

- Demographics (women/younger more likely to attempt; men/older more likely to succeed; widowed/divorced/single)

- Suicidal thoughts, past attempts, specific/lethal plans, access to firearms

- Studies have not found racial predispositions for attempting suicide.8,14

- Factors with a protective effect include positive social support, children at home, responsibility to family, pregnancy (in the absence of peripartum depression), religious beliefs, life satisfaction, and good judgment/problem-solving skills/coping skills.32

- Antidepressants, including SSRIs and TCAs, may increase risk of suicidality during the initial treatment of psychiatric illness when compared with placebo. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning about the risks of suicidal thinking and behavior in adults aged 18 to 24 years during the first 1 to 2 months of treatment for major depression.33

DIAGNOSIS

- At-risk patients should be assessed for thoughts of causing deliberate harm to themselves or others.8,32

- Useful questions include the following:

- Do you feel that life is worth living?

- Do you wish you were dead?

- Have you thought about hurting yourself or ending your life?

- If so, how often have those thoughts occurred?

- Have you gone so far as to think about how you would do so?

- Do you have access to a way to carry out your plan?

- If so, how often have those thoughts occurred?

- Do you feel that life is worth living?

- What keeps you from harming yourself?

- Do you feel that others are responsible for your problems? If so, have you thought about harming or punishing them?

TREATMENT

- Immediate hospitalization with close observation should strongly be considered for patients who are deemed high risk for harm to self or others; evidence psychosis or command hallucinations; have current impulsive behavior, severe agitation, or poor judgment; have a specific suicide plan with persistent intent/ideation; have made precautions against discovery or rescue; have previously attempted suicide using means with high lethality; have significant comorbid psychiatric illness (including depression or substance abuse); and are male and >45 years of age.32

- Causes of suicidality or homicidality (e.g., substance withdrawal or intoxication, psychiatric illness, depression) should be identified and treated appropriately.

- Pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions may be beneficial for the treatment of those without underlying reversible causes, though data are limited and inconsistent.

Medications

- Antidepressant medications (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs) should be used to treat depressed patients with suicidal ideation (see Table 42-2).32

- Lithium reduces the risk of both suicide and suicide attempts when used as long-term maintenance for recurring bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.

- Anticonvulsant agents used as mood stabilizers (e.g., valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine) have not been shown to reduce risk of suicidal behavior.

- Benzodiazepines may ameliorate the suicide risk in an agitated patient because of anxiolytic effects but should be used cautiously as they also disinhibit behavior and enhance impulsivity, particularly in patients with borderline personality disorder.

- No pharmaceutical treatments have clearly shown usefulness for reducing recurrent self-harm not associated with underlying psychiatric illness.31

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

- Clinical consensus suggests skilled psychosocial interventions and specific psychotherapeutic techniques (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT] and dialectical behavior therapy) be used in preventing recurrent self-harm.31,32

- ECT may provide short-term reduction in suicidal ideation, especially in cases of severe depression.32,34

- While recommended, intensive follow-up plus outreach, nurse-led management, emergency contact cards, and hospital admission have not consistently been shown to reduce recurrent self-harm compared with usual care.31,34

REFERRAL

Patients with recurrent or persistent suicidal ideation or self-harm attempts should be cared for in collaboration with psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.

FOLLOW-UP

- Patients who have attempted deliberate self-harm are at risk for future attempts. Repetition is more likely in patients aged 25 to 49 years; unemployed or socioeconomically disadvantaged; divorced, living alone, or with unstable living situations; who have a criminal record; who have a history of stressful traumatic life events or come from a so-called broken home; who have a history of substance abuse, depression, or personality disorder; and who have recurrent feelings of hopelessness or powerlessness.31

- Patients should be routinely monitored by clinicians and family members for evidence of suicidal ideation or recurrent self-harm behaviors. Repeat or long-term hospitalization may be necessary if the patients are persistently a threat to themselves or others.

ANXIETY DISORDERS

- Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health illnesses, affecting nearly one in five American adults.3 The disorders are typified by increased agitation, nervousness, and autonomic tone that disrupt general well-being and function.

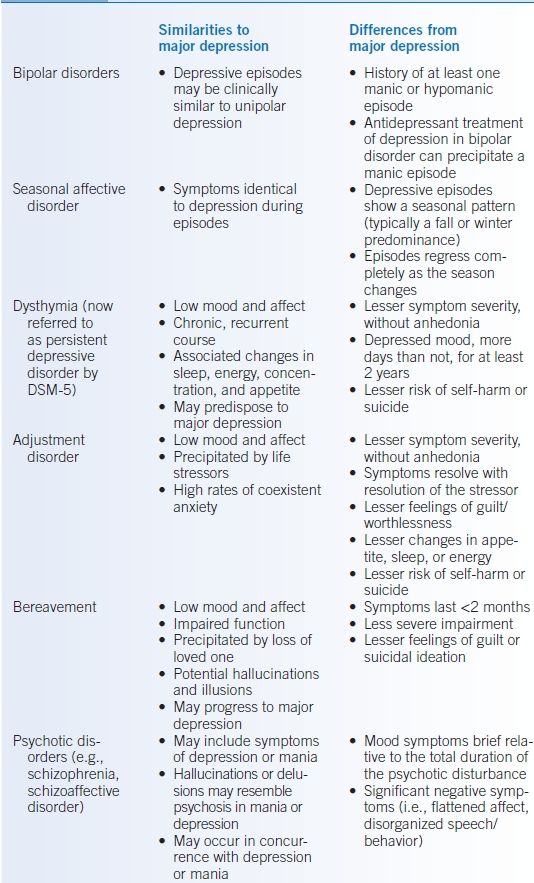

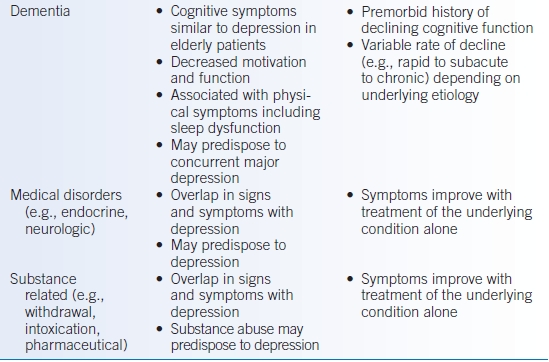

- Anxiety disorders include panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and phobias (see Table 42-3).4,14

- Anxiety disorders frequently coexist with depressive disorders or substance abuse. In addition, most people with one anxiety disorder also have another anxiety disorder.5

- Medical issues such as hypoglycemia, hyperthyroidism, respiratory disease, gastrointestinal disease, and medication side effects all predispose to anxiety disorders. Improvement in these conditions may improve psychiatric issues.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

GAD is characterized by unreasonably excessive concern about common issues, such as finances, family, or work. In GAD, worries become so exaggerated that there is difficulty in performing day-to-day tasks. Other anxiety disorders should be ruled out. DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 criteria are essentially the same.4,12

Epidemiology

- About 3% of American adults suffer from GAD.3 However, studies suggest that GAD may be more prevalent in primary care settings, and suggest that GAD is the anxiety disorder most often seen by general internists.35

- GAD develops gradually and may present at any age, though the median age of onset is about 30 years.

- Similar to other anxiety disorders, GAD is more common in women than in men.5

Etiology/Pathophysiology

- GAD develops from a combination of biologic and psychosocial factors.

- Multiple neurotransmitter and endocrine pathways, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, have been implicated.36 Medical disorders such as chronic pain, endocrine diseases, and pulmonary conditions may predispose to generalized anxiety.

- Social and environmental stressors, including recent unfavorable events, also likely contribute to GAD.37

- Maladaptive cognitive strategies play a prominent role in GAD. Worry subjectively increases preparedness for feared events but also causes distress over them. GAD patients subconsciously overvalue the worry process and, over time, develop a cycle of worry proneness.35

- Predisposition to GAD appears modestly inheritable but incompletely understood.36,37

Associated Conditions

- Patients with GAD may exhibit worsening job performance, changes in interpersonal relationships, multiple unexplained symptoms or frequent medical visits, concentration difficulties, sleep disturbances or chronic fatigue, and increasing alcohol/tobacco use.

- Patients with GAD are at high risk for developing another anxiety disorder or major depression.37,38

- More than one-third of GAD patients abuse alcohol or illicit drugs.35

- GAD is a chronic condition but can be improved or controlled with treatment. Twenty-five percent of adults with GAD will be in full remission after 2 years, and 38% will have a remission after 5 years.37

- However, nearly one-third of patients in full remission will have a clinically significant relapse within 5 years; the rate is even higher for those with only partial remission.37

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- The hallmark of GAD is excessive and difficult-to-control worry about multiple issues, often despite insight that the anxiety is more intense than warranted.36

- Unlike other anxiety disorders, worry in GAD is not limited to a specific trigger or social situation (e.g., phobias). GAD patients may experience discrete panic attacks but their anxiousness is persistent, pervasive, and focused on multiple components of normal daily living.

- In addition to excessive worry, patients may exhibit other nonspecific signs including irritability or fatigue, difficulty concentrating, increased startle responses, and/or sleep disturbances including insomnia.38

- Patients with GAD frequently have associated somatic symptoms including headaches, muscle tension and myalgias, difficulty swallowing (i.e., globus hystericus), nausea, tremor or tics, sweating, lightheadedness or dyspnea, frequent urination, and/or hot flashes.35,36,38

- Symptom severity fluctuates over time and is often worse during periods of increased stress.36

- GAD patients often seek medical care for their somatic symptoms, but do not necessarily volunteer concerns about their psychological ones.35,36

- Screening can be performed using the 7-item Anxiety Scale (GAD-7), which has reasonable reliability, sensitivity, and specificity.39

- Further assessment should be made through a validated quantitative measure such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire IV (GAD-Q-IV).40

- Initial evaluation should include the following:

- Screening for suicidality or self-harm

- Assessment of anxiety severity and impact

- Screening for concurrent psychiatric issues including depression and substance abuse

- Screening for suicidality or self-harm

- Appropriate laboratory and radiographic testing should be performed if there are potentially treatable medical conditions contributing to the patient’s symptomatology.

Differential Diagnosis

- Many medical conditions are associated with or contribute to anxiety disorders including cardiac, endocrine, infectious, metabolic, neoplastic, and neurologic disorders as well as effects due to medications, diet, toxins, and illicit substances.

- GAD must be distinguished from other psychiatric conditions (Table 42-3).4,14

TREATMENT

- Both medications and nonpharmacologic treatments benefit GAD, but it is uncertain which is more effective. At least one study involving a pediatric population has shown that sertraline in combination with CBT is more effective than either treatment alone.41

- Strongly consider psychiatrist or mental health specialist referral if there are severe symptoms or functional impairment; signs of psychosis or suicidal ideation; comorbid medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse disorders; plans for psychotherapy; need for frequent or close follow-up; and/or patient requests for specialist treatment.38

Medications

- The SSRIs and SNRIs have all shown benefit over placebo in treating GAD and should be considered first-line agents (Table 42-3).35,37,42

- Although data are limited, there appears to be minimal efficacy and tolerability differences amongst these medications.37

- Patients typically require at least 4 to 6 weeks of therapy with SSRIs before symptoms improve.

- Although data are limited, there appears to be minimal efficacy and tolerability differences amongst these medications.37

- Imipramine has demonstrated benefit for GAD; other TCAs are less well studied.35,37,42 However, the side effect profile of imipramine suggests that it should be considered a second-line agent.

- Benzodiazepines have proven utility in the temporary mitigation of GAD (Table 42-4).37,43

- Short-term adjuvant therapy with long-acting benzodiazepines may benefit some patients during the initial phase of treatment with SSRIs or SNRIs.

- Trials have not shown benefit over other agents when used for long-term anxiety control. The prolonged use of benzodiazepines in GAD also increases risk for dependence, sedation, and traffic accidents.37

- These agents should be limited to use for breakthrough anxiety.

- There does not appear to be significant within-class efficacy differences among the long-acting benzodiazepines.37

- Short-term adjuvant therapy with long-acting benzodiazepines may benefit some patients during the initial phase of treatment with SSRIs or SNRIs.

- Hydroxyzine (a first-generation antihistamine) has been successfully used as an anxiolytic in GAD.37 Data regarding its efficacy have been mixed, however, and sedating side effects may limit its usefulness.

TABLE 42-4 Frequently Used Benzodiazepines

Short, <6 hours; interm., 6–20 hours; long, >20 hours; bid, twice daily; tid, three times daily; qid, four times daily; hs, at bedtime.

Higher relative potency designates more potent agents (i.e., inverse of dose equivalents). All benzodiazepines have longer-lasting and more potent effects in patients with hepatic impairment. CYP-450 interactions change the metabolism of many benzodiazepines. Patients with panic disorder may need higher total doses than those with GAD for symptom relief.

Modified from Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Concise Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

- Psychotherapy is an effective treatment for GAD.44

- CBT focused on insight, education, and coping strategies reduces anxiety symptoms and is beneficial as both short- and long-term treatment.35,36,39

- CBT is more effective than other psychological therapies.45

- CBT should be administered by a skilled therapist. Data suggest that the success of psychotherapy is linked to the experience level of practitioners, though some patients may benefit from nonspecialist delivered supportive psychotherapy alone.35

- CBT is more effective than other psychological therapies.45

- Relaxation training had historically been used in treating GAD but has not been well studied in clinical trials.35 Related methods such as applied relaxation and mindful meditation appear to have some efficacy.37

- Aerobic exercise and exercise training likely have general anxiety-lowering benefits but have not been well-studied in the treatment of GAD.30

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Panic attacks are discrete sudden periods of intensive apprehension or terror, often accompanied by physiologic symptoms (e.g., palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness) and feelings of impending doom DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 criteria are essentially the same.4,12

- Panic disorder is diagnosed, however, only when recurrent unpredictable panic attacks are followed by at least 1 month of persistent concern about having another panic attack or significant behavioral changes related to the attacks.4,14

- Agoraphobia (an irrational fear of public places, crowds, or being outside the home) may also develop in the setting of recurrent panic attacks.

Epidemiology

- Approximately 3% of American adults have panic disorder; of these, one in three develops agoraphobia. Panic disorder is twice as common in women, and moderately heritable.5,46

- Panic disorder typically first manifests in late adolescence or early adulthood, but the age of onset extends throughout adulthood.5,38,46

Etiology/Pathophysiology

- The underpinnings of panic disorder and agoraphobia are multifactorial and incompletely understood. Dysfunction of serotonin-, norepinephrine-, and GABA-mediated central nervous system pathways may be implicated. In addition, patients may have idiosyncratic changes in autonomic system regulation.

- Panic disorder also appears to have an important cognitive-behavioral aspect, and its onset is often preceded by stressful life events.35,38,46

Associated Conditions

- Patients with panic disorder may exhibit worsening job performance, changes in interpersonal relationships, multiple unexplained symptoms or frequent medical visits, concentration difficulties, sleep disturbances or chronic fatigue, and/or increasing alcohol/tobacco use.

- Patients with panic disorder are at high risk for developing another anxiety disorder, depression, or substance abuse.

- The risk of suicide and attempted suicide is markedly higher in patients with panic disorder.46

- Panic disorder is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease.35

- If untreated, panic disorder chronically recurs with an unpredictable waxing and waning course. Patients may experience residual symptoms, including agoraphobia and somatization, even during periods when actual panic attacks are quiescent.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Not all patients who experience panic attacks will develop panic disorder.38 The impact of panic disorder stems mainly from worry about future panic attacks or the possible implications of physical symptoms.

- Panic attacks may feel truly life threatening. Patients are often consumed by recurrent “what if?” worries related to the perceived dangerousness of panic attacks and may persistently seek medical consultations despite reassurance.

- Patients with panic disorder typically first present to emergency or primary care settings with unexplained symptoms rather than direct concerns about panic attacks. Complaints commonly include the following: noncardiac chest pain, palpitations, unexplained faintness, unexplained vertigo and dizziness, irritable bowel symptoms, dyspnea or tachypnea, feelings of impending doom or depersonalization, and nocturnal awakenings from panic attacks.35,38

- Agoraphobia sufferers typically have more severe impairment and panic symptomatology but are more likely to seek treatment than other panic disorder patients.35

- Screening with two questions from the Anxiety and Depression Detector yields a high sensitivity and moderate specificity for panic disorder35,47:

- In the past 3 months, did you ever have a spell or an attack when all of a sudden you felt frightened, anxious, or very uneasy?

- In the past 3 months, would you say that you have been bothered by nerves or feeling anxious or on edge?

- If the patient answers “yes” to either screening question, further evaluation should be performed using a quantitative standardized instrument.

- In the past 3 months, did you ever have a spell or an attack when all of a sudden you felt frightened, anxious, or very uneasy?

- Initial evaluation should include the following:

- Screening for suicidality or self-harm

- Assessment of panic disorder severity

- Screening for concurrent psychiatric issues including substance abuse

- Screening for suicidality or self-harm

- Appropriate laboratory and radiographic testing should be performed if there are potentially treatable medical conditions (e.g., hyperglycemia, hyperthyroidism, or a pheochromocytoma) contributing to the patient’s symptomatology.

Differential Diagnosis

- As noted, many medical conditions are associated with or contribute to anxiety disorders.

- Panic disorder must be distinguished from other psychiatric conditions (Table 42-4).4,14

TREATMENT

- Panic disorder is highly treatable and the majority of patients receive benefit with appropriate therapy.38

- Strongly consider psychiatrist or mental health specialist referral if there are severe symptoms or functional impairment; agoraphobia; recurrent panic attacks despite treatment; signs of psychosis or suicidal ideation; comorbid medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse disorders; plans for psychotherapy; need for frequent or close follow-up; and/or patient requests for specialist treatment.38

Medications

- Medications improve anxiety and decrease the frequency of panic attacks.35,38,46

- SSRIs are considered the drugs of choice in treating panic disorder (Table 42-3). Efficacy appears similar among the SSRIs. Data also suggest comparable efficacy for venlafaxine.35,46

- Benzodiazepines are beneficial in acutely reducing the symptoms of panic attacks but have a high potential for abuse, dependence, and tolerance (Table 42-4).35,38,46 Short-term adjuvant therapy with long-acting benzodiazepines may benefit some patients during the initial phase of other therapies.

- Bupropion has not been adequately studied to support its use for panic disorder, especially as many patients report that its activating effects actually worsen panic symptoms.35

- β-blockers may help some patients control physical symptoms, though they have not shown effectiveness for panic disorder in controlled trials.35,38

- Gabapentin may exhibit anxiolytic benefit in panic disorder, though data are mixed.48

- Side effects that mimic panic attack symptoms may occur during either initiation or discontinuation of medications. Antidepressants should be started at half the usual initial dose and gradually titrated when increased or withdrawn. Frequent reassurance may aid patient compliance.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies

- CBT is effective for treating panic disorder and is supported by robust clinical trial data.

- It is unclear whether CBT is superior to pharmacotherapy but some data suggest that the benefits of CBT may be long lasting.35,46

- Combined treatment with CBT and antidepressants may be more beneficial than with either modality alone for short-term symptom reduction.46

- More than one-third of patients with panic disorder either cannot tolerate or do not respond to appropriate SSRI or venlafaxine therapy. Many patients who do not respond to medication will, however, respond to CBT.

- CBT should be administered by a skilled therapist. Data suggest that the success of psychotherapy is linked to the experience level of practitioners.

- It is unclear whether CBT is superior to pharmacotherapy but some data suggest that the benefits of CBT may be long lasting.35,46

- Aerobic exercise, breathing techniques, and relaxation/biofeedback exercises may indirectly improve panic disorder through lowering hyperreactivity to bodily sensations, though few studies have evaluated their use.30,35,46 Similarly, yoga and meditation have theoretical benefit but have been formally evaluated only on a limited basis.49

PSYCHOSIS AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Psychosis denotes a disturbed perception of reality including hallucination, delusion, or thought disorganization.

- Psychotic states are associated with increased agitation, aggression, impulsivity, and behavioral dysfunction.

- Psychosis may be due to

- Underlying psychiatric illness (e.g., schizophrenia, mania)

- Substance abuse (e.g., cocaine intoxication, alcohol withdrawal)

- Medication side effects (e.g., corticosteroids)

- Medical illnesses (e.g., delirium, encephalitis)

- Underlying psychiatric illness (e.g., schizophrenia, mania)

- Patients have variable insight into their psychosis and may or may not recognize the derangements in their thought processes.14,50

Epidemiology

- Approximately 1% of the American adult population has schizophrenia and it is equally frequent in men and women.

- Schizophrenia typically first manifests in men during their late teens or early 20s; women usually exhibit symptoms in their 20s or early 30s.5

- Schizoaffective and mood disorder-associated psychosis may be more common in women.

- Approximately 80% of untreated manic patients develop psychotic symptoms. Psychotic symptoms in the context of mania or depression are often, but not always, congruent with mood (e.g., grandiose delusions).

Etiology/Pathophysiology

- The pathophysiology of schizophrenia is poorly understood. Some studies demonstrate abnormally elevated dopaminergic activity, altered neural network activation patterns, and anatomic atrophy in the central nervous system of patients with schizophrenia.51,52

- These changes likely result from complex interactions between multiple genes and environmental factors.51

Associated Conditions

- A total of 40% to 50% of patients with schizophrenia suffer from substance abuse issues with tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.8

- Schizophrenic patients are also predisposed to be victims of violence and are at higher risk of suicide, depression, homelessness, and unemployment.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Types of psychotic symptoms include the following:

- Hallucinations are false perceptions in one of the sensory modalities (e.g., auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory). Auditory hallucinations are more common in psychoses due to a primary psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia. While present in primary psychotic disorders, visual hallucinations should be treated as organic until proven otherwise.

- Delusions are false beliefs that are firmly held despite obvious evidence to the contrary. Delusions are distinct from ideas typical of the patient’s background cultural, religious, or familial belief system. Common delusions include thoughts of persecution, thoughts of grandiosity or superhuman abilities, and thoughts of hyperreligiosity. Delusions are characterized as bizarre or nonbizarre on the basis of their degree of plausibility.

- Delusions of reference are a common type of delusion in which a patient believes that neutral information refers specifically to him or her. Patients may believe in the receipt of special messages transmitted from the television, radio, newspaper, or psychic communications.

- Illogical thought processes are evidenced by nonsensical speech and loose associations, with accompanying functional impairment, bizarre behaviors, and agitation or aggression.

- Agitation can manifest as both heightened emotional arousal and increased motor activity. Agitation is not exclusive to psychosis but frequently accompanies it.

- Hallucinations are false perceptions in one of the sensory modalities (e.g., auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory). Auditory hallucinations are more common in psychoses due to a primary psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia. While present in primary psychotic disorders, visual hallucinations should be treated as organic until proven otherwise.

- Schizophrenia is a severe, chronic disorder characterized by periods of active psychosis and an insidious deterioration of social, occupational, and personal functioning. Symptoms are typically subcategorized as follows:

- Positive symptoms, including psychosis with hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorganization

- Negative symptoms, including blunted affect, loss of social interest, decreased motivation, anhedonia, and decreased verbal communication

- Cognitive symptoms, including deficits in memory, attention, verbal processing, and executive function

- Affective symptoms, such as bizarre or inappropriate affect and predisposition for major depression

- Positive symptoms, including psychosis with hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorganization

- Psychotic patients should undergo a complete mental status examination.

- Patients should be specifically questioned about hearing voices; seeing things others do not see; sensations of things touching or crawling on the skin; experiencing odd smells or tastes; fears that others are following, spying on, or wish to cause them harm; thought reading; special messages from television or radio; unusual religious experiences; and special powers or abilities.

Diagnostic Criteria/Differential Diagnosis

- Schizophrenia is characterized by abnormalities of thought (e.g., delusion, hallucinations, and language disorganization) for at least 6 months. These abnormalities significantly affect social functioning. The DSM-5 criteria are essentially the same as the prior DSM-IV-TR criteria.4,12

- Schizophrenia must be distinguished from other psychotic conditions (Table 42-5).4,14

- Many medical illnesses and certain drug intoxications are associated with psychotic symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree