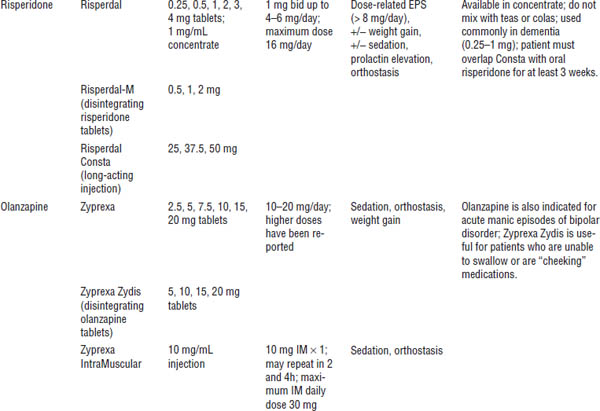

Table 29-1. Typical (Conventional or Older) Antipsychotics

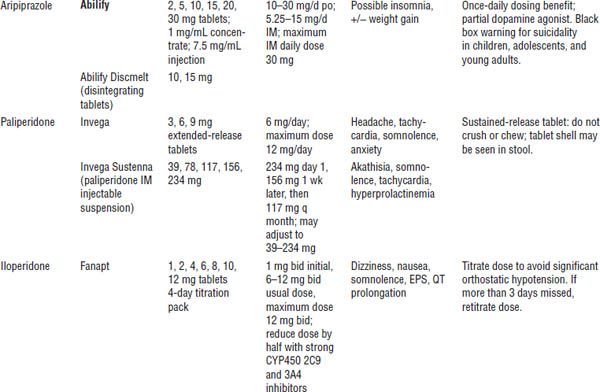

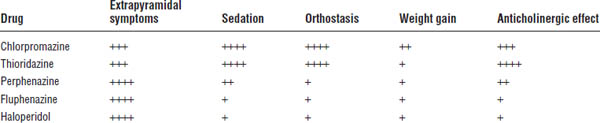

Table 29-2. Adverse Effects of Typical Antipsychotic Medications

Neuroleptic effects

Neuroleptic effects are “secondary” negative symptoms including reduced initiative, lessened interest in environment, and blunted affect.

Orthostasis

Alpha adrenergic blockade results in orthostatic hypotension. Severity depends on the drug used. Low-potency formulations promote more orthostasis than do high-potency formulations. Orthostasis is usually seen in the first few hours or days of treatment, and the patient usually develops tolerance.

This condition is especially problematic in elderly patients.

Weight gain

Weight gain is very prominent in patients taking these medications. Low doses should be used. Appropriate diet and exercise should be encouraged to offset weight gain.

Anticholinergic effect

Severity depends on the drug used. Low-potency drugs of this type are more sedating than high-potency ones.

Dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, and urinary hesitancy may occur. Use high-potency agents in patients bothered by anticholinergic side effects.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) are most likely attributed to an imbalance in dopamine and acetylcholine. Antipsychotics cause a hypodopaminergic state.

Dystonic reactions

Reactions usually occur within 24–96 hours of initiating or changing the dose. They present as painful, involuntary muscle spasms in skeletal muscles (most commonly in the facial or neck muscles but sometimes in the back, arm, and leg muscles).

Treatment is benztropine (Cogentin) 1–2 mg intramuscular (IM) or diphenhydramine (Benadryl) 25–50 mg IM every 30 minutes until the reaction is relieved. Prophylaxis with oral therapy is usually initiated.

Akathisia

Akathisia usually occurs within a few weeks of initiating antipsychotic therapy. It is described as a subjective feeling of discomfort, usually seen as motor restlessness of the legs (inability to stand still or sit still).

Akathisia may be treated by decreasing the dose; changing the drug; or adding lipophilic β-blockers (e.g., propranolol), benzodiazepines, clonidine, or anticholinergic agents.

Pseudoparkinsonism

Pseudoparkinsonism usually occurs after months or years of therapy. This condition resembles Parkinson’s symptoms (e.g., cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, tremor, shuffling gait).

It is treated with amantadine (Symmetrel) 100 mg bid or anticholinergics (including benztropine, diphenhydramine, and trihexyphenidyl).

Other adverse effects

Tardive dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is an irreversible drug-induced movement disorder that occurs after years of antipsychotic therapy. It is caused by long-term suppression of dopamine.

A triad of symptoms characterize TD:

■ Choreoathetosis (splayed, writhing fingers)

■ Oral or buccal movements (grimacing, bruxism, lip-smacking)

■ Protrusion of the tongue

The only treatment is prevention (i.e., use the lowest effective dose of antipsychotic). However, various therapies (vitamin E, lecithin, vitamin B6) may help alleviate symptoms. Switching to clozapine may be helpful because it has not been reported to cause TD.

Monitor for TD by administering the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) to all patients taking antipsychotics.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) has a low incidence and high mortality. It is thought to be due to dopamine blockade. Clinical presentation of NMS is as follows:

■ Rapid progression (< 24 hours)

■ Body temperature > 100.4°F

■ Lead-pipe rigidity

■ Hypertension

■ Diaphoresis

■ Increased heart rate

■ Incontinence

■ Increased liver function test (LFT), creatinine phosphokinase (CPK), and white blood count (WBC)

Treatment is as follows:

■ Transport patient to an emergency room immediately.

■ Discontinue antipsychotic medication.

■ Administer supportive therapy (cooling blankets, hydration); the dopamine agonist bromocriptine (Parlodel); and the smooth muscle relaxant dantrolene (Dantrium).

Endocrine and metabolic effects

Such effects include amenorrhea, galactorrhea, and gynecomastia caused by hyperprolactinemia.

Dopamine regulates prolactin release. When dopamine is blocked, prolactin is elevated.

Other effects include weight gain and decreased glucose tolerance.

Dermatologic effects

(especially in long-term therapy)

Allergy to medication, photosensitivity, and pigmentation problems may occur.

Hypothalamic effects

Temperature dysregulation (i.e., sensitivity to extreme temperatures) is possible.

Cardiac effects

QT prolongation is possible. Effects are more common with thioridazine (black box warning).

The recommendation is to obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG) for all patients on antipsychotics.

Ophthalmologic effects

Pigmentary retinopathy is associated with daily thioridazine doses > 800 mg. Melanin deposits occur on the cornea and may lead to blindness.

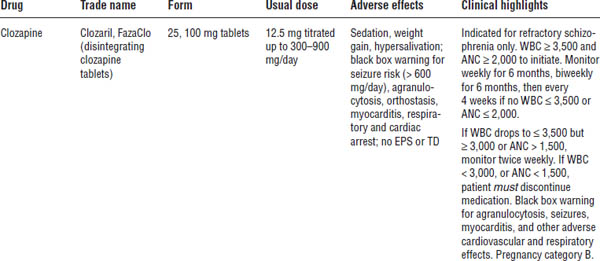

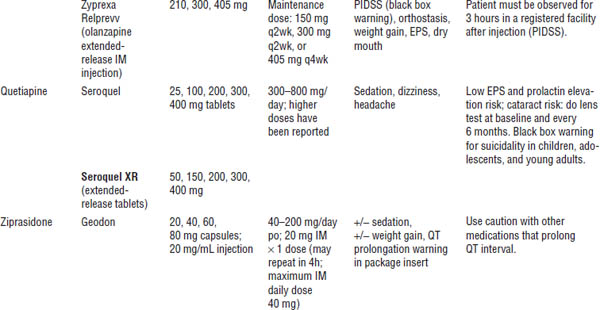

Atypical (newer) antipsychotics

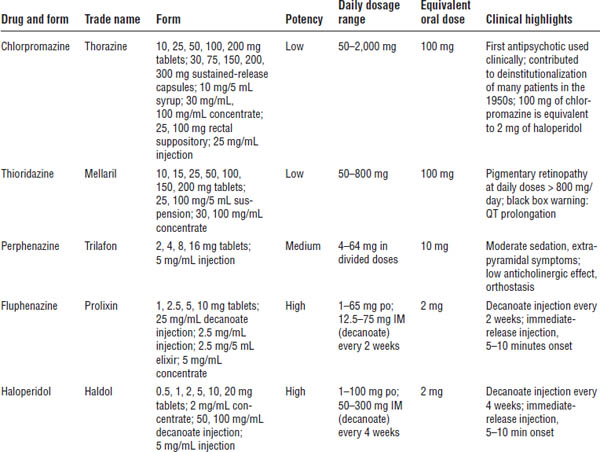

See Table 29-3 for an overview of these drugs.

Table 29-3. Atypical Antipsychotics

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

ANC, absolute neutrophil count; PIDSS, post-injection delirium/sedation syndrome.

No universally accepted definition of atypical exists, but these drugs generally have the following features:

■ Side effects are less severe (little or no EPS, minimal to no prolactin increase, less risk of TD).

■ More weight gain, more lipid abnormalities, and a greater risk of diabetes are seen with these drugs.

■ A dose-dependent increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death is seen, possibly because of prolongation of the QT interval similar to typical antipsychotics.

■ Decreased affinity for the dopamine receptor is present.

■ Results from the CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness) showed very high discontinuation rates for all antipsychotics secondary to inefficacy or intolerable side effects. No difference was seen between perphenazine and atypicals (except olanzapine).

■ There is a black box warning for increase in mortality with atypical antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia, and atypical antipsychotics are not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis.

Mechanism of action

These drugs are weak dopamine and dopamine-2 receptor blockers that block serotonin and α-adrenergic, histaminic, and muscarinic receptors in the central nervous system.

Treatment Strategies

Acute schizophrenia

■ Decrease danger to self and others.

■ Increase dosage of the antipsychotic until behavior improves or side effects limit the dose.

■ Haloperidol or fluphenazine (immediate release) 5–10 mg IM and lorazepam 2 mg IM q4h prn may be used for psychosis or agitation. An anticholinergic may also be needed (e.g., benztropine or diphenhydramine for EPSs).

■ Olanzapine 10 mg IM may be used and can be repeated in 2 hours and again 4 hours later, for a maximum of 30 mg/day for psychosis or agitation.

■ Patients may use ziprasidone 10 mg IM administered every 2 hours or 20 mg IM administered every 4 hours, for a maximum of 40 mg/day for psychosis or agitation.

Maintenance

■ Start an atypical antipsychotic at a recommended dose or continue a conventional agent (if it was effective for the patient before hospital admission).

■ Positive symptoms will respond first.

■ Monitor for side effects, and emphasize compliance.

■ Lifelong therapy is usually needed.

■ Use lowest effective dose to decrease risk of side effects (e.g., TD).

Recommended monitoring for patients on atypical antipsychotics

■ Fasting glucose and lipids and blood pressure at baseline and at 12 weeks

■ Weight (body mass index) at baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks, and then quarterly

■ Waist circumference at baseline and then annually

Noncompliance and alternative dosing

Haloperidol decanoate (Haldol-D)

The dosage conversion from po to IM is as follows: po daily dose × 10 = IM dose every 4 weeks. For example, 20 mg daily dose × 10 = 200 mg every 4 weeks.

Steady state is reached in 8–12 weeks.

Fluphenazine decanoate (Prolixin-D)

The dosage conversion from po to IM is as follows: 1 mg po = 1.25 mg IM. For example, 20 mg daily dose × 1.25 mg = 25 mg IM every 2 weeks.

Steady state is reached in approximately 6 weeks.

Depot administration technique

Both medications are suspended in sesame seed oil. They are very viscous. Ensure that the patient has no allergy to sesame seed oil.

Administer in gluteal or deltoid muscle with a 16- or 18-gauge needle.

Risperidone long-acting injection (Risperdal Consta)

Overlap with po medication for 3 weeks.

The recommended dose is 25 mg every 2 weeks. The maximum dose is 50 mg every 2 weeks. Alternate IM administration between buttocks.

Steady state is reached in approximately 8 weeks.

Use the diluent and needle supplied in the pack to reconstitute and administer injection.

29-4. Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness) is a recurrent mood disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 0.8–1.6%. This disorder is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Incidence is equal in females and males. Onset is usually between ages 8 and 44. The first episode for females is usually marked by a depressive episode. For males, it is usually marked by a manic episode.

Types and Classifications

■ Bipolar I: This type is characterized by the occurrence of manic episodes and major depressive episodes.

■ Bipolar II: This type is characterized by the occurrence of hypomanic episodes and major depressive episodes.

■ Cyclothymia: This type is defined as numerous episodes of hypomania and depressive episodes that cannot be classified as major depressive episodes. Diagnosis requires that cyclothymia occur for at least a 2-year period.

Clinical Presentation

See DSM-5 for complete diagnostic criteria.

Mania

Mania is characterized by heightened mood (euphoria), flight of ideas, rapid or pressured speech, grandiosity, increased energy, decreased need for sleep, irritability, and impulsivity. Judgment is significantly impaired (e.g., increased risk-taking behavior). Marked impairment also exists in social or occupational functioning.

Psychotic features are usually present. Hospitalization is needed.

Changes in sleeping patterns (especially insomnia) commonly initiate manic episodes.

Drug-induced causes include antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors); bronchodilators (albuterol, salmeterol); stimulants; xanthines (caffeine, theophylline); dopamine agonists (bromocriptine, amantadine); and sympathomimetics.

Note: The STEP-BD (Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder) trial showed that antidepressants used in combination with mood stabilizers did not increase the risk of inducing mania in bipolar depression. However, this combination was not associated with increased efficacy.

Hypomania

Hypomania is a less severe form of mania. This disorder usually does not cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning.

Many patients find this state highly desirable because they experience a great sense of well-being and feel productive, creative, and confident.

Mixed Features

A specifier “with mixed features” may be applied to episodes of mania or hypomania when depressive features are present.

Rapid cycling

In rapid cycling, the patient experiences more than four mood episodes in a year. Mood episodes may occur in any combination.

Rapid cycling primarily occurs in women (70–90%). The prognosis is usually poor.

Etiology

The etiology is unknown; however, the leading hypothesis supports genetic etiology. Other theories include neurotransmitter involvement, circadian rhythm, and kindling hypothesis.

Clinical Course

The mean age of onset is 21 years. The first episode for females is usually depression. For males, it is mania.

Untreated episodes may last from weeks to months. A high mortality rate exists because of suicide. Comorbid substance abuse is very common (60–70%).

Treatment Principles and Goals

Acute

In acute cases, the goal is to control the current episode (i.e., slow down the patient and reduce harm to self and others).

Maintenance

Maintenance goals are as follows:

■ Prevent or minimize future episodes.

■ Maintain drug therapy, and reduce adverse effects.

■ Prevent drug interactions.

■ Educate the patient and family about the disorder.

■ Provide adequate follow-up services (including substance abuse treatment).

■ Maximize the patient’s functional status and quality of life.

Drug Therapy

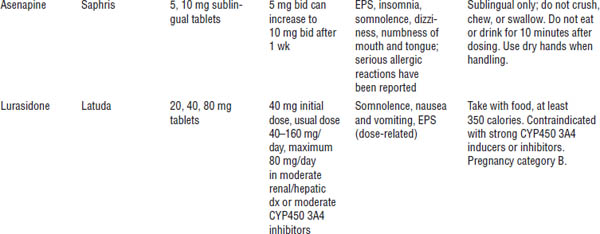

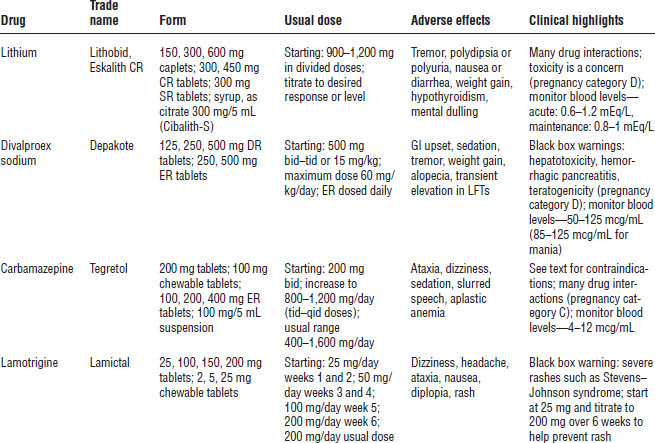

Table 29-4 provides information about mood stabilizers.

Lithium

Indications

Lithium is indicated for acute treatment and prophylaxis of manic episodes associated with bipolar disorders. It is effective for both the manic and the depressive components.

Mechanism of action

The mechanism of action is unknown. Various theories suggest that lithium facilitates γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) function, alters cation transport across cell membranes in nerve and muscle cells, or influences reuptake of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) or norepinephrine (NE).

Contraindications

Contraindications include renal disease, severe cardiovascular disease, history of leukemia, first trimester of pregnancy, and hypersensitivity to lithium.

Precautions

Use with caution in patients who have thyroid disease, patients who have sodium depletion, patients who are receiving diuretics, or dehydrated patients.

Monitoring (baseline and follow-up)

■ Thyroid panel: Lithium may cause hypothyroidism. Test baseline and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) every 6–12 months or as clinically indicated.

■ Serum creatinine (SCr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN): Lithium is 100% renally eliminated. Test baseline and every 3 months for patients with renal dysfunction and every 6–12 months otherwise or as clinically indicated.

■ Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: Lithium may cause leukocytosis and may reactivate leukemia. Test baseline and then as clinically indicated.

■ Electrolytes: In the event of hyponatremia, lithium toxicity may occur. Test electrolytes every 6–12 months or as clinically indicated.

■ ECG: Lithium causes flattened or inverted T-waves. This condition is reversible. Test baseline and every 6–12 months or as clinically indicated.

■ Urinalysis: Lithium may decrease specific gravity. Perform urinalysis every 6–12 months.

■ Pregnancy test: Lithium may cause cardiovascular defects (e.g., Ebstein’s anomaly). Perform pregnancy test every 6–12 months or as clinically indicated.

■ Lithium level: Lithium reaches steady-state levels in 4–5 days (half-life = ~ 24 hours). Obtain the level in the morning immediately before next dose (acute: 0.6–1.2 mEq/L; maintenance: 0.8–1 mEq/L). Lithium levels should be checked after each dose increase and before the next dose increase. Steady-state levels are reached approximately 5 days after dose adjustment. Periodic monitoring of lithium levels should occur every 6 months or more frequently if clinically indicated.

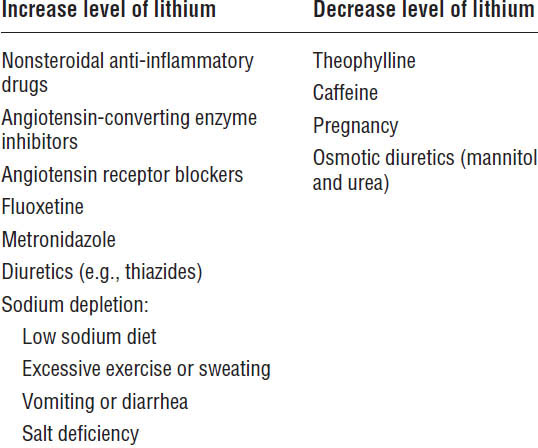

Drug interactions

Table 29-5 summarizes the drug interactions associated with lithium.

In addition, several toxicity concerns are associated with the drug:

■ Mild toxicity (serum levels 1.5–2 mEq/L): Gastrointestinal (GI) upset (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea); muscle weakness; fatigue; fine hand tremor; and difficulty with concentration and memory

■ Moderate toxicity (serum levels 2–2.5 mEq/L): Ataxia, lethargy, nystagmus, worsening confusion, severe GI upset, coarse tremors, and increased deep tendon reflexes

■ Severe toxicity (serum levels > 3 mEq/L): Severely impaired consciousness, coma, seizures, respiratory complications, and death

Table 29-5. Drug Interactions with Lithium

Toxicity is treated as follows:

■ Discontinue lithium, and initiate gastric lavage.

■ Correct electrolyte and fluid imbalances.

■ Monitor neurologic changes.

■ Give supportive care.

■ Give dialysis if indicated.

Patient information

■ Routinely monitoring serum lithium levels is important.

■ Maintain a steady salt and fluid intake.

■ Do not crush or chew extended- or slow-release dosage forms.

Divalproex sodium

Divalproex sodium is indicated for bipolar disorder. It is considered first-line treatment for acute manic episodes. It has unlabeled use for prophylaxis of manic episodes, is effective for rapid cyclers and patients with dysphoric mood, and is helpful in the management of agitation and aggression.

Converting from divalproex sodium delayed release to divalproex sodium extended release is not a 1:1 ratio. When converting from divalproex sodium delayed release to divalproex sodium extended release, the total daily dose must be increased by 8–20% to the nearest available dosage form.

Mechanism of action

Its mechanism of action is unknown, but divalproex sodium is thought to increase GABA or mimic its action at the postsynaptic receptor site.

Contraindications

Contraindications include the following:

■ Hepatic dysfunction

■ Hypersensitivity to divalproex sodium

■ Patients < 2 years old

■ Pregnancy

With respect to pregnancy, valproic acid (VPA) may cause neural tube defects. If the benefit outweighs the risk, supplement with 4–5 mg/day of folic acid to decrease risk of fetal damage. Perform pregnancy test every 6–12 months.

Monitoring

VPA

■ VPA level reaches steady state in 5 days (half-life = 9–16 hours); 50–125 mcg/mL is optimal.

■ Draw level periodically as clinically indicated.

LFT

■ Test baseline, every 6–12 months, with dose changes, or as clinically indicated.

■ Divalproex sodium is hepatically eliminated; it carries a black box warning for hepatotoxicity.

CBC with differential

■ Test baseline, every 6–12 months, with dose changes, or as clinically indicated.

■ VPA may cause thrombocytopenia.

Platelet count

■ Test at baseline with dose changes, or as clinically indicated.

■ Hematologic abnormalities may be seen with serum levels above 100 mcg/mL.

Serum ammonia

■ Test at baseline with dose changes, or as clinically indicated.

■ Divalproex may cause hyperammonemia.

Drug interactions

■ Divalproex sodium is a cytochrome P450 (CYP450) 2C19 enzyme substrate, a CYP450 2C9 and 2D6 inhibitor, and a weak CYP450 3A3/4 inhibitor.

■ Interactions occur with carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin. Increased sedative effects occur with phenobarbital and benzodiazepines.

Patient information

■ Take with food to avoid GI upset.

■ Take a multivitamin with selenium and zinc if alopecia (hair loss) occurs.

■ It is important to monitor VPA levels routinely.

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine (CBZ) is considered second-line therapy for acute and prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder.

Mechanism of action

The mechanism of action is unknown.

Monitoring

Monitor CBC with differential, electrolytes, LFTs, SCr or BUN, and ECG (if the patient is > 40 years old or has a preexisting heart disease).

CBZ is an autoinducer. Monitor levels routinely, especially during first few months of therapy. The optimal level is 4–12 mcg/mL.

Contraindications

Contraindications include history of previous bone marrow depression and hypersensitivity to CBZ.

Drug interactions

■ CBZ is a CYP450 2C8 and 3A3/4 enzyme substrate.

■ It is a CYP450 1A2, 2C, and 3A3/4 inducer.

■ CBZ may induce the metabolism of benzodiazepines, clozapine, corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, VPA, warfarin, phenytoin, and tricyclic antidepressants (plus others).

■ Cimetidine, clarithromycin, diltiazem, verapamil, metronidazole, and lamotrigine (plus others) inhibit CBZ.

Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

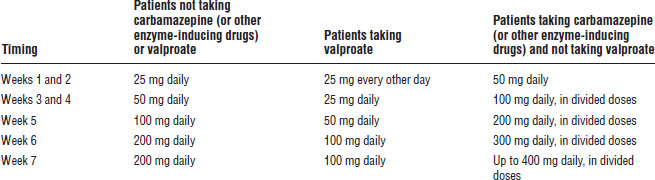

Lamotrigine is approved for maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder. Titration of the dose is required to monitor for signs and symptoms of severe and potentially life-threatening skin rashes including Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (Table 29-6). Co-administration with VPA increases the risk.

Drug interactions and effects

■ CBZ, phenytoin, oral contraceptives, rifampin, and phenobarbital decrease lamotrigine concentrations.

■ VPA increases lamotrigine concentrations.

■ Adverse effects include nausea, headache, tremor or anxiety, and sedation.

Other therapies

Atypical antipsychotics

These agents are approved for treatment of bipolar disorder. Olanzapine and fluoxetine (Symbyax) is indicated for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar disorder.

Table 29-6. Lamotrigine Dose Titration

Gabapentin (Neurontin)

This agent may be useful as adjunctive therapy for bipolar disorder. No significant drug interactions exist. No drug serum level monitoring is required.

Gabapentin is renally eliminated. It has mild sedative effects (sedation, ataxia, fatigue).

Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal)

This agent is structurally similar to CBZ (ketoanalogue of CBZ). It is sometimes used as a mood stabilizer in patients with bipolar disorder, but further studies are needed.

No autoinduction problems exist, and there are no drug serum levels to monitor. It appears to have fewer drug–drug interactions than CBZ.

Topiramate (Topamax)

This agent may be useful for treatment of bipolar disorder, but further studies are needed. Doses are usually lower than those indicated for treating seizure disorders.

Topiramate may cause weight loss, difficulties with concentration, nephrolithiasis, acute myopia, and secondary angle closure.

Calcium channel blockers

These agents are usually reserved as last-line therapy. Data in the literature are inconsistent about using verapamil for mania (other calcium channel blockers may be effective).

Although these agents are not routinely used, they could possibly be used in pregnancy.

29-5. Major Depression

Major depression is a prevalent and serious illness in the United States. It affects 10 million to 14 million people of all ages.

The condition is treatable but grossly undertreated. Most cases go unrecognized, which may be due to the social stigma surrounding depression. Several myths contribute to the problem of undertreatment (e.g., major depression is caused by personal weakness or an inability to handle life’s problems).

Epidemiology

The lifetime prevalence rate is 17%. One in four females (10–24%) is affected. One in 8 males (5–12%) is affected.

Major depression is most common between the ages of 25 and 44.

Risk factors include the following:

■ Family history

■ Female

■ Previous depressive episode

■ Previous suicide attempt

■ Comorbid medical or substance abuse disorder

Etiology

The etiology is unknown; however, there are many hypotheses, including the following:

■ Dysregulation of neurotransmitters

■ Decreased concentration of certain neurotransmitters

■ Genetic basis for the disorder

■ Medications that may induce or worsen depression:

• Beta-blockers

• Barbiturates

• Benzodiazepines

• Corticosteroids

• Parkinson’s agents

• Topiramate

• Varenicline

Clinical Presentation

Physical findings

■ Fatigue

■ Pain (i.e., headaches, back pain, GI upset)

■ Sleep disturbances (usually insomnia)

■ Appetite disturbances (usually decreased appetite)

■ Psychomotor retardation or agitation

Emotional symptoms

■ Anhedonia

■ Depressed mood for most of the day

■ Hopelessness or helplessness

■ Inappropriate feelings of guilt and worthlessness

■ Anxiety or worry

■ Suicidal ideation

Cognitive symptoms

■ Decreased ability to concentrate

■ Indecisiveness

Laboratory studies

There are no diagnostic laboratory tests for depression, but the following lab work should be conducted to rule out other illnesses that may manifest as depressive symptoms:

■ CBC with differential

■ Thyroid function tests

■ Urine drug screen

Medical conditions that may contribute to the development or worsening of depression include cancer, cerebrovascular accident, diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus, multiple sclerosis, myocardial infarction (MI), Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, thyroid abnormalities, and vitamin deficiency. Possible drug-induced causes of depression should also be ruled out, including corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, propranolol, clonidine, and methyldopa.

Prognosis

Seventy percent of patients are responsive to antidepressant therapy. Following the first episode, 50–60% of patients will have another episode; following the second episode, 70–80% will have a third; and following the third, 90% will have another.

If untreated, an episode may resolve spontaneously within 6 to 24 months.

Approximately 15% of patients will commit suicide. Risk factors for suicide include being male, older than 50, or unemployed; having recently lost a job or spouse; being socially isolated; having access to a weapon; and experiencing comorbid substance abuse.

Males are more likely to commit suicide, but females are more likely to attempt suicide. Males commonly use more violent means of suicide (e.g., firearms and hanging) than do females (e.g., slashing of wrists and drug overdoses).

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

At least five symptoms (see previous discussion of clinical presentation) must be present mostly every day for a 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning. At least one of the symptoms must be depressed mood or anhedonia.

Treatment Principles and Goals

Goals are as follows:

■ Improve patient’s ability to function and quality of life.

■ Reduce or eliminate target symptoms with an antidepressant.

■ Optimally, incorporate psychotherapy.

■ Prevent relapse.

All antidepressants are equally effective in a given population:

■ Response varies from person to person.

■ Each differs in side effect and drug-interaction profiles.

■ None are “speed” or “uppers.”

Note:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree