Prosthetic Arteriovenous (Av) Access

Robyn A. Macsata

Anton N. Sidawy

For the first time since 1995, in 2007, the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) reported that the incidence rate of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) fell by 2.1%, to 354 per million population, while the prevalence rate continued to rise by 2.0%, to 1,165 per million population. The cost of care of these patients also continued to rise by 6.1%, to $23.9 billion, which was 5.8% of Medicare’s annual budget. Not surprising to vascular access surgeons, a large portion of these expenditures come during the transition from chronic kidney disease to ESRD and are related to dialysis catheter use, hospitalization for access failure, declotting procedures, repeated access placements, and infectious complications.

Taking these numbers into account, along with the known higher long-term patency rates and lower complication rates of autogenous arteriovenous (AV) access in comparison with prosthetic AV access, we attempt to place autogenous AV access in all our patients with ESRD requiring hemodialysis. In order to achieve success, we stress early referral of these patients from our nephrologists, a thorough preoperative evaluation including noninvasive vascular laboratory and contrast studies if necessary, routine postoperative follow-up with secondary procedures if indicated, and prompt treatment of AV access thrombosis. Unfortunately, even with these efforts, it is sometimes impossible to construct an autogenous AV access, requiring placement of a prosthetic AV access; to achieve success in this population, adherence to excellent technique is even more imperative.

The National Kidney Foundation-Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-KDOQI) guidelines recommend that patients be referred to a vascular access surgeon for permanent AV access when their creatinine clearance is less than 25 mL/min. Once preoperative evaluation is complete, if we feel the patient will require a prosthetic AV access, we delay construction of the access until 3 to 6 weeks prior to the initiation of dialysis; this is due to the fact that prosthetic access patency is limited by time of access placement, and not by access use.

Preoperative Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

A thorough patient history is taken documenting patient’s dominant extremity, recent history of peripheral intravenous lines, site of indwelling or previous central venous lines including pacemakers and defibrillators, all previous access procedures, any history of trauma or previous nonaccess surgery to the extremity, and all comorbid conditions. On physical examination, the brachial, radial, and ulnar arteries are evaluated for compressibility and equality; an Allen’s test is performed to evaluate for palmar arch patency. With a venous tourniquet in place, the cephalic and basilic veins are evaluated for diameter, distensibility, and continuity; the arm is examined for any signs of central venous stenosis including prominent venous collaterals, edema, or a differential in extremity diameter.

Arterial Assessment

If any abnormality is noted on clinical arterial examination, the patient is further evaluated with segmental pressures and duplex ultrasound. Any abnormalities noted on noninvasive testing, including pressure gradients between the bilateral upper extremities, arterial diameters less than 2.0 mm, and nonpatent palmar arches, are further evaluated with an arteriogram. Any inflow stenosis is treated first with endovascular techniques such as angioplasty and/or stenting, and if not amenable or unsuccessful, open surgical techniques such as patch angioplasty or bypass.

Venous Assessment

If superficial veins cannot be visualized or any abnormality is noted on the superficial venous examination, the patient is further evaluated with superficial venous duplex; using duplex the superficial veins are examined for diameter, distensibility, and continuity. We only use superficial veins for autogenous access that are greater than 2.5 mm in diameter.

If any central venous stenosis is suspected by history or any abnormality is noted on physical examination, the patient is further evaluated with deep venous duplex; if the deep venous duplex is nondiagnostic or any central venous stenosis is noted, the patient is further evaluated with a venogram. Any central venous stenosis is treated first with endovascular techniques such as angioplasty and/or stenting, and if not amenable or unsuccessful, open surgical techniques such as internal jugular to axillary venous bypass or subclavian vein turndown.

In patients nearing dialysis, the risk of contrast arteriogram or venogram is weighed against the need for an access to mature before beginning dialysis; in this population, we use renal protective agents prearteriogram, including intravenous fluids, N-acetylcysteine, and sodium bicarbonate.

Access Location Selection

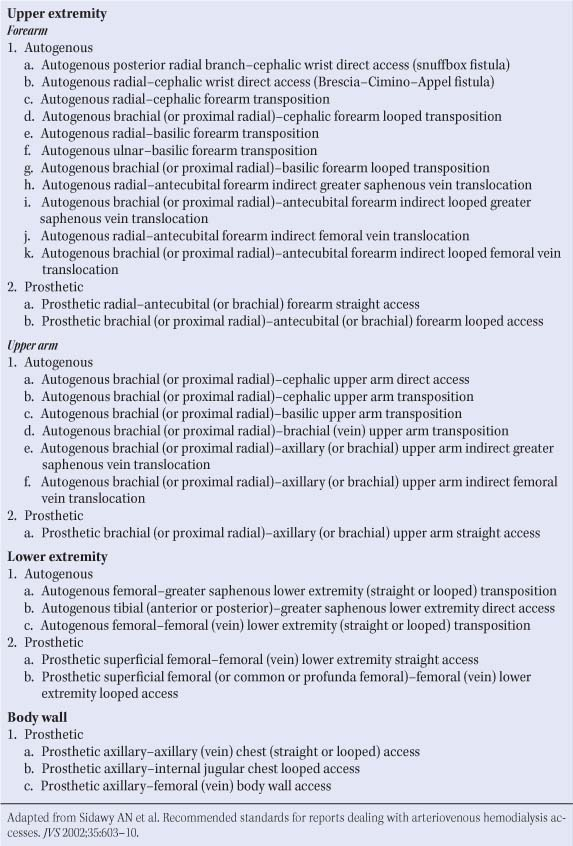

Table 1 lists the various types of autogenous and prosthetic AV access available in the upper and lower extremities and body wall; when planning AV access, a few general principles apply.

Given their superior patency rates and lower complication rates, autogenous AV accesses are always attempted before a prosthetic AV access.

Due to easier accessibility and lower infection rates, upper extremity access sites are used first, with the nondominant arm given preference over the dominant arm.

To preserve proximal sites for future accesses, AV accesses are placed as far distally in the extremity as possible.

Autogenous AV access configurations, in order of preference, are direct arteriovenous anastomosis, venous transpositions, and venous translocations.

For purposes of this chapter, we will focus on prosthetic AV access.

Forearm

In the upper extremity, the cephalic and basilic veins are both options for autogenous AV access; however, when unavailable, we perform a prosthetic upper extremity access, beginning in the forearm. Sources of arterial inflow include the distal or proximal radial and brachial arteries; we

use the most distal artery in the arm felt to be adequate by preoperative evaluation for inflow to preserve more proximal arteries for future accesses. Sources of venous outflow include the antecubital vein or the brachial vein; we use the superficial system if felt to be adequate on exploration to help with venous dilation of the upper arm superficial veins for future accesses. Therefore, when the distal radial artery is adequate, we perform a prosthetic radial–antecubital (or brachial) forearm straight access (Fig. 1). If the distal radial artery is inadequate but the brachial or proximal radial artery is adequate, we perform a prosthetic brachial (or proximal radial)–antecubital (or brachial) forearm looped access (Fig. 2).

use the most distal artery in the arm felt to be adequate by preoperative evaluation for inflow to preserve more proximal arteries for future accesses. Sources of venous outflow include the antecubital vein or the brachial vein; we use the superficial system if felt to be adequate on exploration to help with venous dilation of the upper arm superficial veins for future accesses. Therefore, when the distal radial artery is adequate, we perform a prosthetic radial–antecubital (or brachial) forearm straight access (Fig. 1). If the distal radial artery is inadequate but the brachial or proximal radial artery is adequate, we perform a prosthetic brachial (or proximal radial)–antecubital (or brachial) forearm looped access (Fig. 2).

Table 1 Arteriovenous Access Configuration | |

|---|---|

|

One of the interesting debates in this area is whether, after exhausting the forearm autogenous options, the surgeon should recommend a forearm prosthetic access before proceeding to an upper arm autogenous access. We handle this decision by having a discussion with the patient about this alternative option and its advantages and disadvantages, and allow the patient to make an informed decision. If a prosthetic forearm access is chosen, we explain to the patient that this access is used as a “bridge” to an autogenous upper arm access; we minimize attempts to salvage this access to avoid damaging the venous outflow so it can still be used for an autogenous upper arm access.

Upper Arm

When use of the forearm has been exhausted, efforts are directed to the upper arm. Like the forearm, the cephalic and basilic veins are both options for autogenous access; however, when unavailable, we perform a prosthetic upper arm access. Sources of arterial inflow include the proximal radial and brachial arteries; we use the most distal artery in the arm felt to be adequate by preoperative evaluation for inflow to preserve more proximal arteries for future access. Sources of venous outflow include the proximal brachial and axillary vein. Therefore, in patients with no adequate vein, a prosthetic brachial (or proximal radial)–axillary (or brachial) upper arm straight access (Fig. 3) is performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree