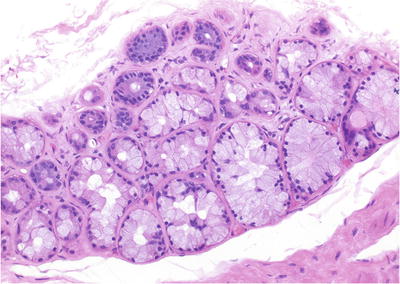

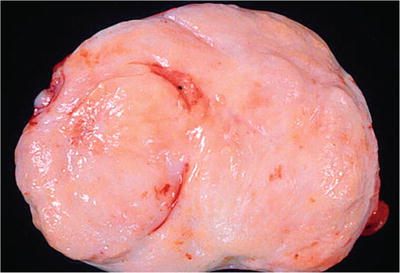

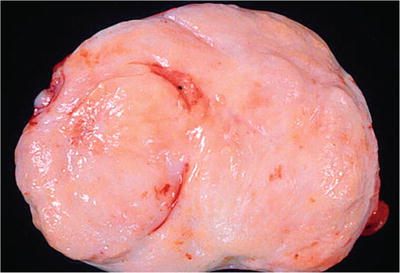

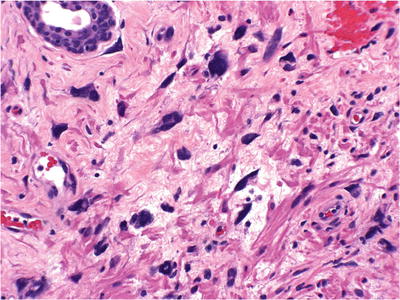

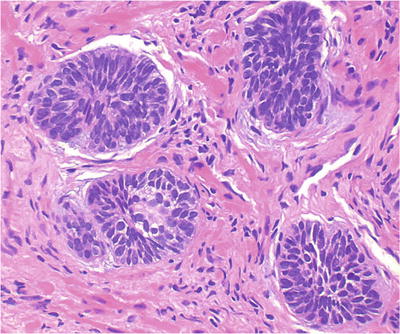

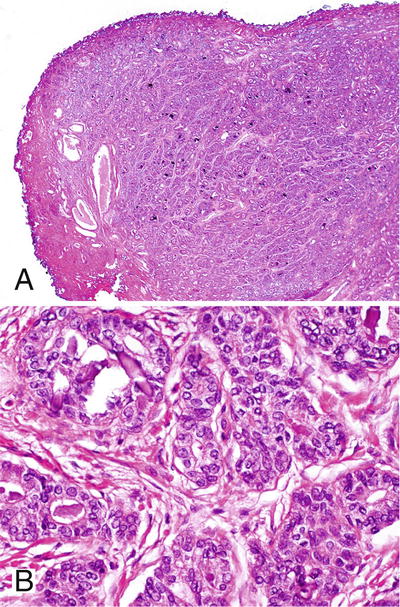

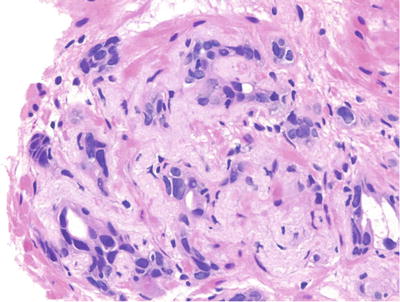

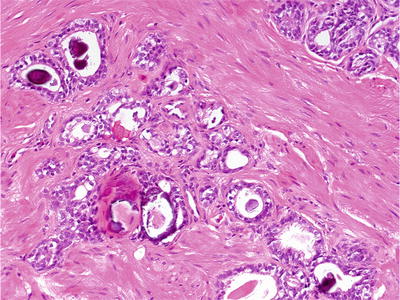

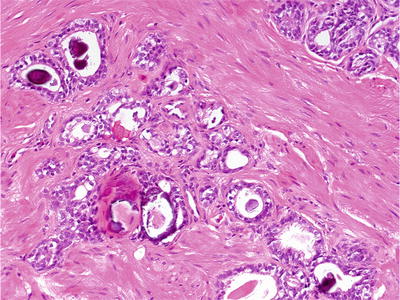

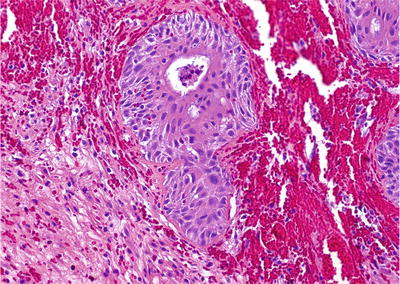

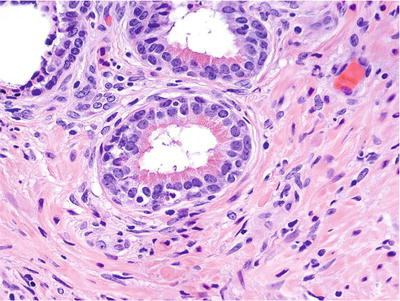

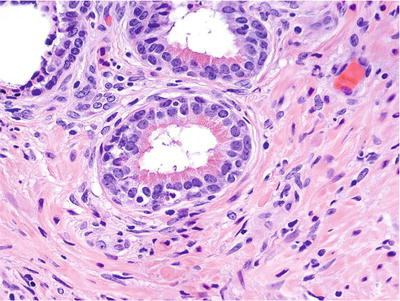

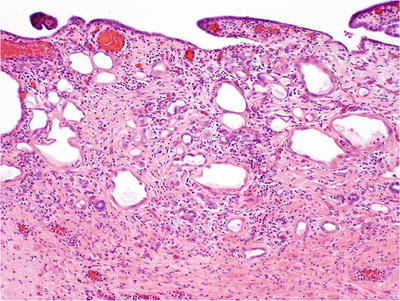

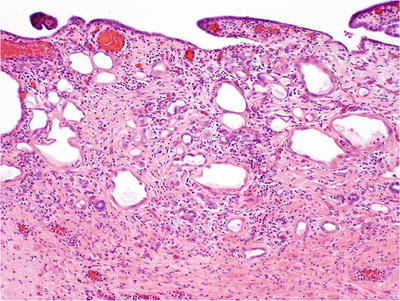

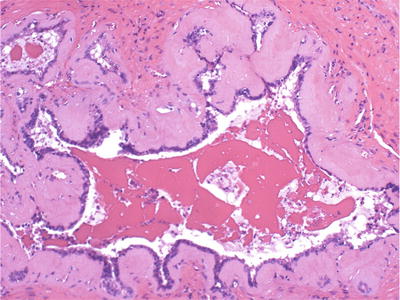

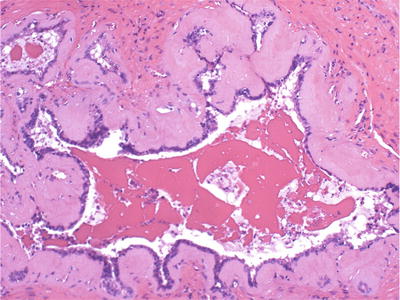

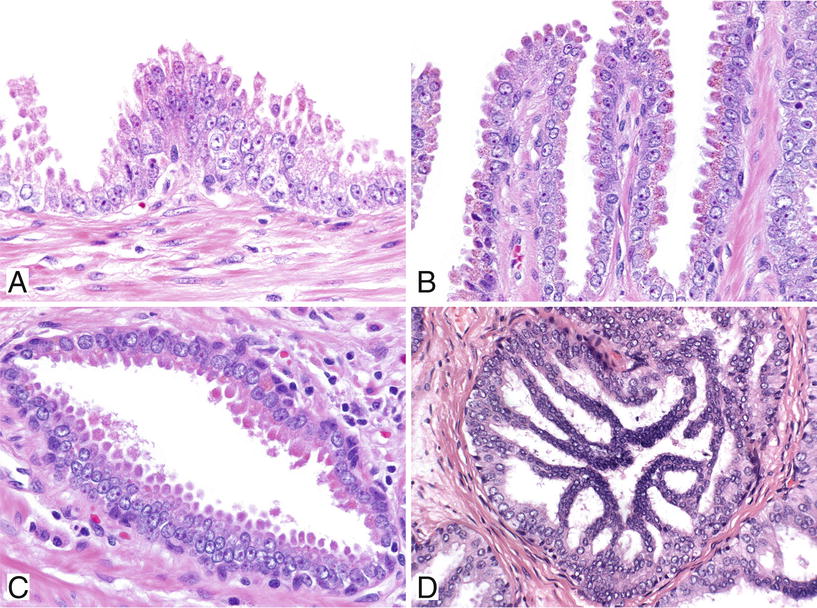

Fig. 38.1.

Acute prostatitis with microabscess formation.

♦

Acinar destruction and epithelial cell degeneration

♦

Stromal hemorrhage and edema

♦

Abscess is a rare complication, especially in immunocompromised patients

Chronic Bacterial and Nonbacterial Prostatitis

Clinical

♦

Chronic nonbacterial prostatitis is more common than chronic bacterial prostatitis (E. coli)

♦

Chlamydia trachomatis and Ureaplasma urealyticum are common etiologic agents

♦

Often follows an indolent clinical course with relapses and remissions

Microscopic

♦

Epithelial degeneration and metaplasia

♦

Chronic inflammation

Differential Diagnosis

♦

High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN)

Partial acinar involvement, nuclear stratification, and prominent nucleoli

Caution is urged in diagnosing prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) in the setting of inflammation

Granulomatous Prostatitis

Clinical

♦

Prior history of urinary tract infection is common (Table 38.1)

Table 38.1.

Etiology of Granulomatous Prostatitis

Infections Bacterial: Tuberculosis (AFB staining), syphilis Fungal: Coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis Parasitic: Schistosomiasis Viral: Herpes zoster |

Iatrogenic Postsurgery or radiation Post-BCG treatment |

Malakoplakia |

Systemic granulomatous disease Allergic Sarcoidosis Systemic vascular diseases Wegner granulomatosis Polyarteritis nodosa Churg-Strauss vasculitis |

Idiopathic (most common) |

♦

Suspicious for carcinoma on digital rectal examination

♦

Probably caused by blockage of prostatic ducts and stasis of secretion

Microscopic

♦

Specific etiology often cannot be determined from histologic examination

♦

Glandular disruption, epithelial degeneration, and metaplasia

♦

Granulomatous inflammation with or without necrosis

♦

Polymorphous chronic inflammation composed of multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) negative, prostate acid phosphatase (PAP) negative, cytokeratin negative, CD68 positive, and other macrophage markers positive

Variants

♦

Xanthoma

Incidental finding in elderly men

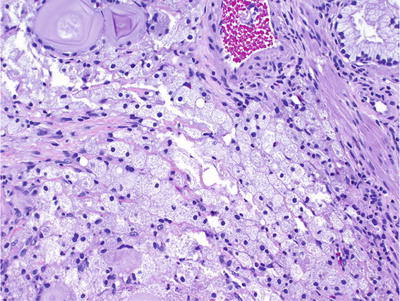

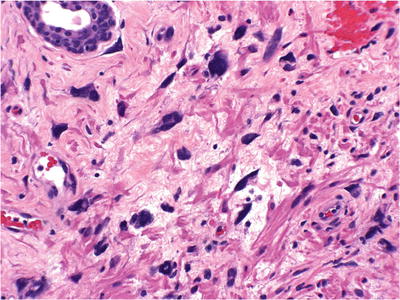

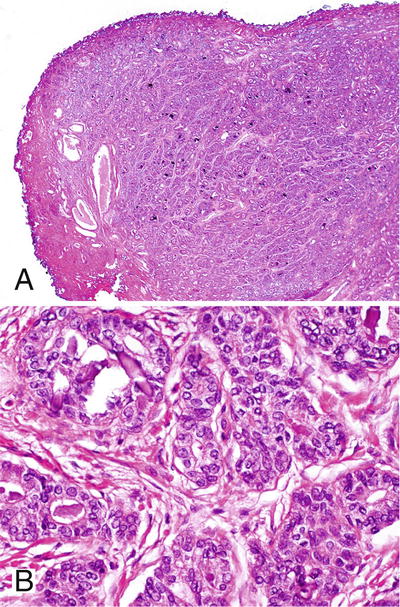

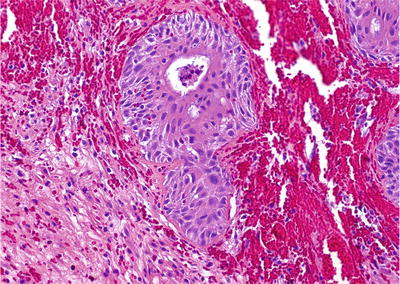

Clusters and sheets of lipid-laden histiocytes in a nodular configuration (Fig. 38.2)

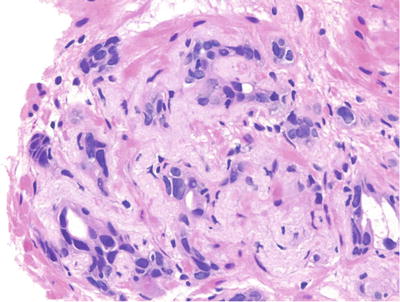

Fig. 38.2.

Xanthoma .

CD68 positive, cytokeratin negative

♦

Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis

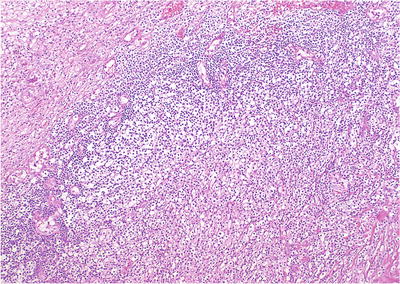

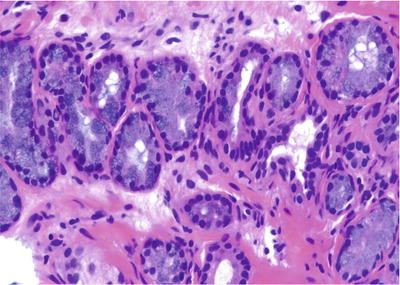

Nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis

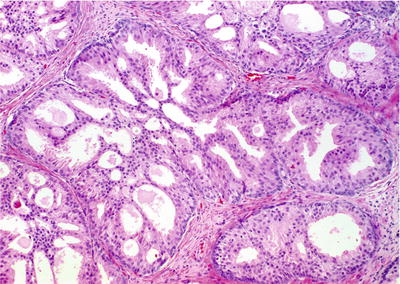

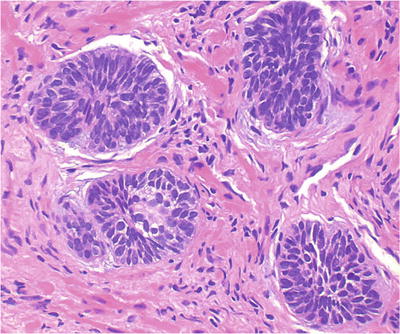

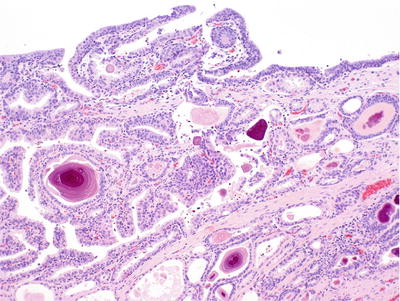

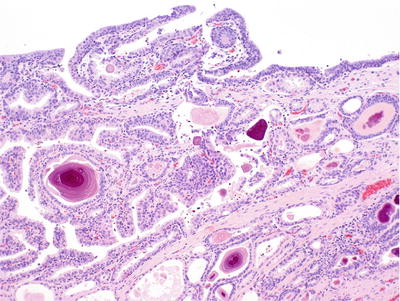

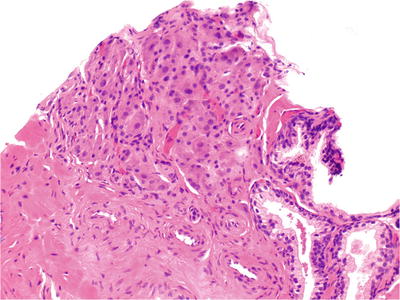

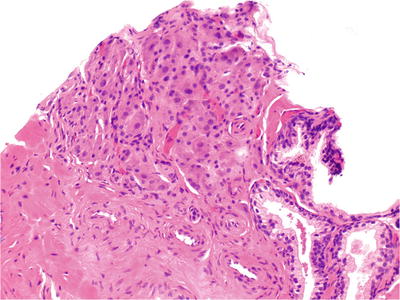

Composed predominantly of sheets of epithelioid histiocytes (Fig. 38.3)

Fig. 38.3.

Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis. Lymphocytes rim a massive monomorphous collection of macrophages with abundant clear cytoplasm. This case was initially misdiagnosed as high-grade carcinoma.

Polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate

Associated with atrophy and acinar disruption

♦

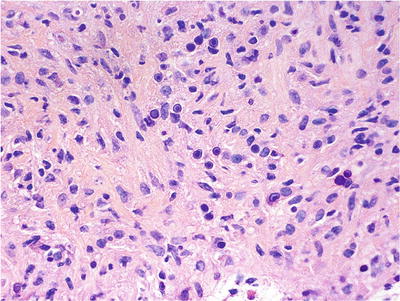

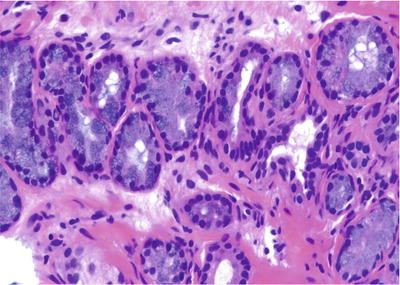

Malakoplakia

Due to defective intracellular lysosomal digestion of bacteria

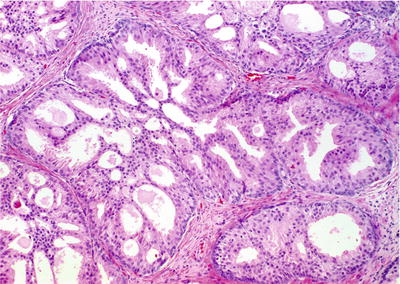

Intracellular and extracellular Michaelis-Gutmann bodies are characteristic of the lesion (Fig. 38.4)

Fig. 38.4.

Malakoplakia. Numerous Michaelis-Gutmann bodies are noted.

The Michaelis-Gutmann bodies represent bacterial debris within phagolysosomes, highlighted by PAS and von Kossa stains

♦

Wegener granulomatosis

Stellate and geographic granulomas with palisading histiocytes

Necrotizing vasculitis involving small- and medium-sized vessels

♦

Postsurgical granulomatous prostatitis

Occurs up to years following surgery

Central zone of fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by peripheral palisading of epithelioid histiocytes

Benign Lesions and Mimics of Adenocarcinoma

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Other Forms of Hyperplasia

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Clinical

♦

Occurs in 50% or more of men >50 years

♦

Often presents with lower urinary tract symptoms

♦

Develops in transition zone, resulting from stromal and epithelial proliferation

♦

Etiology and pathogenesis are not completely understood

♦

Inflammation is implicated in the pathogenesis of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH); patients with inflammation have larger prostates, higher serum PSA, and greater risk of urinary retention

♦

Hormonal regulation is mainly via dihydrotestosterone (DHT), derived from testosterone by the activity of 5-α-reductase

♦

Growth factors also play an important role in the development of BPH; epidermal growth factor (stimulatory) and transforming growth factor-β (inhibitory) alter prostatic growth

Macroscopic

♦

Yellow-gray rubbery to firm and bulging nodules in the transition zone and periurethral region (Fig. 38.5)

Fig. 38.5.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) , stromal variant. Bulging from the cut surface of this adenectomy specimen is a fleshy firm stromal nodule.

♦

For transurethral resection specimens, submit a minimum of six cassettes for the first 30 g of tissue and one cassette for every 10 g thereafter

Microscopic

♦

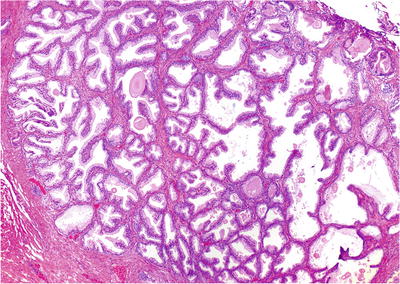

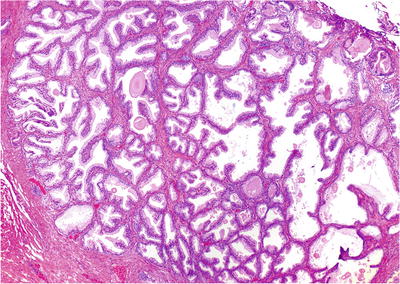

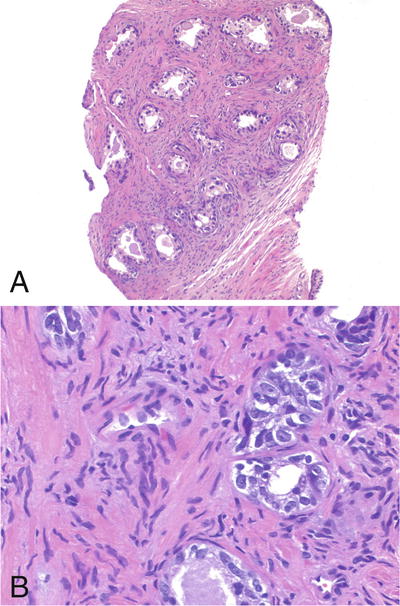

Epithelial and stromal hyperplasia in the transition zone and periurethral region (Fig. 38.6)

Fig. 38.6.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia. This epithelium-predominant round nodule is typical.

♦

Stromal nodules consist of fibromuscular spindle cell proliferation with thin- or thick-walled vessels and scattered lymphocytic infiltrate (mainly T-helper cells)

♦

Often associated with prostatic infarct with squamous and urothelial metaplasia

♦

At least part of a nodule should be present for the diagnosis to be made on biopsies (uncommon)

♦

Multiple variants (see below) (Table 38.2)

Table 38.2.

Histopathological Variants of Nodular Hyperplasia

Variant | Microscopic features | Usual location |

|---|---|---|

Stromal hyperplasia with atypical giant cells | Stromal nodules in the setting of cellularity and nuclear atypia | Transition zone |

Basal cell hyperplasia (BCH) | Proliferation of basal cells, two or more cells in thickness; may have prominent nucleoli (atypical basal cell hyperplasia) or form a nodule (basal cell adenoma) | Transition zone |

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) | Localized proliferation of small acini in association with BPH nodule which architecturally mimics adenocarcinoma but lacks cytologic features of malignancy | Transition zone |

Postatrophic hyperplasia | Atrophic acini with epithelial proliferative changes; easily mistaken for adenocarcinoma due to architectural distortion | All zones |

Cribriform hyperplasia | Acini with distinctive cribriform pattern, often with clear cytoplasm; easily mistaken for proliferative acini of the central zone | Transition zone |

Sclerosing adenosis | Circumscribed proliferation of small acini in a dense spindle cell stroma without significant atypia; usually solitary and microscopic | Transition zone |

Hyperplasia of mesonephric remnants | Rare benign lobular proliferation with colloid-like material in the lumina; may mimic nephrogenic metaplasia focally; acini do not apparently express PSA or PAP | All zones (very rare) |

Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia | Small benign acinar proliferation | Verumontanum |

Stromal Hyperplasia with Atypical Giant Cells

♦

Often occurs in the transition zone

♦

Benign variant of nodular hyperplasia

♦

Increased stromal cellularity with bizarre giant cells and nuclear degenerative changes (Fig. 38.7)

Fig. 38.7.

Stromal hyperplasia with atypical giant cells.

♦

Nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromasia, and pyknosis

♦

Lacks the circumscription of leiomyoma

♦

No mitotic figures

♦

Some have applied the term prostatic stromal tumor of uncertain malignant potential, but this is discouraged as it lumps stromal hyperplasia (benign) with phyllodes tumor (malignant)

Cribriform Hyperplasia

♦

Often occurs in the transition zone

♦

Variant of nodular hyperplasia

♦

Cribriform pattern of acinar proliferation with intact basal cell layer (Fig. 38.8)

Fig. 38.8.

Cribriform hyperplasia. Note the variable size and collapsible nature of the luminal fenestrations. Unlike high-grade PIN and ductal adenocarcinoma, there are no cytologic abnormalities. In this preparation, the basal cell layers at the periphery of the acini are especially prominent.

♦

Uniform cells with clear or granular cytoplasm and inconspicuous nucleoli

♦

Basal cells probably contain the regenerative or stem cells of the prostate

♦

Occurs in 6% of biopsies and 9% of transurethral resection specimens

Basal Cell Proliferation

Basal Cell Hyperplasia

♦

Often occurs in the transition zone

♦

Variant of BPH

♦

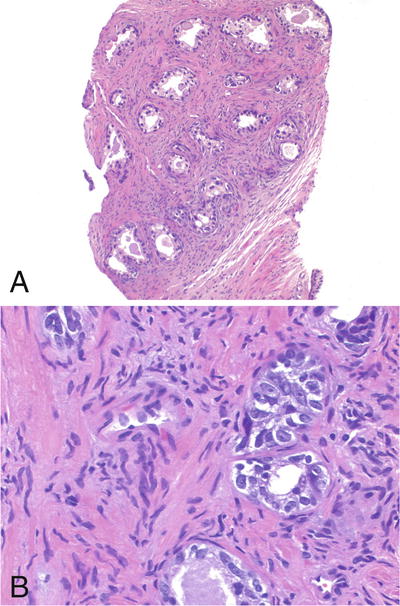

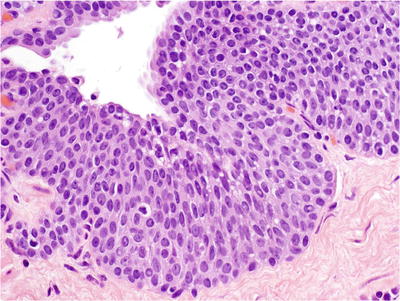

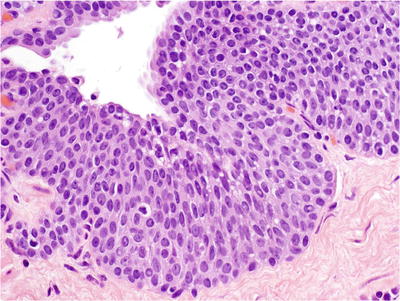

Proliferation of basal cells with multiple layers (>2) (Fig. 38.9)

Fig. 38.9.

Basal cell hyperplasia . These tight nests of basaloid cells are characteristic of BCH.

♦

Often eccentrically located with partial involvement of acini, retaining the overlying columnar or cuboidal secretory cells

♦

Basal cells have enlarged nuclei, fine powdery chromatin, and occasional nuclear grooves:

Nuclear “bubble” artifact or intranuclear vacuole often seen in formalin-fixed tissue but not in frozen section

♦

Often associated with chronic inflammation

Atypical Basal Cell Hyperplasia

♦

Same as basal cell hyperplasia BCH) but with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 38.10)

Fig. 38.10.

Atypical basal cell hyperplasia. (A) The acini are set in a moderately fibrotic stroma. (B) The acini contain basal cells with prominent nucleoli.

♦

Require >10% of cells displaying prominent nucleoli for diagnosis

Basal Cell Adenoma

♦

Variant of BPH

♦

Nodule formation with BCH (Fig. 38.11)

Fig. 38.11.

Basal cell adenoma from a transurethral resection specimen. The lesion is well circumscribed (A). Basal cells have powdery nuclei with fine chromatin (B).

♦

Well-circumscribed solid nests and aggregates of hyperplastic basal cells in a condensed fibrous stroma

♦

Plump nuclei, high nucleus-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and inconspicuous nucleoli

♦

High-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 positive (Table 38.3)

Table 38.3.

Immunohistochemical Profiles of Benign Lesions in the Prostate

PSA/PAP | HMW CK | Cytokeratin a | S-100 protein | SMA | Zonal predilection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Xanthoma/xanthogranulomatous prostatitis | – | – | – | – | – | Peripheral |

Nephrogenic metaplasia | – | + | + | – | – | Periurethral |

Postatrophic hyperplasia | + | + | + | – | – | Peripheral |

Atypical basal cell hyperplasia | −/+ | + | + | −/+ | – | Transition |

Cribriform hyperplasia | + | + | + | – | – | Transition |

Sclerosing adenosis | + | + | + | – | + | Transition |

Stromal hyperplasia with atypia | – | – | + | – | + | Transition |

Hyperplasia of mesonephric remnants | – | + | + | – | – | Unknown |

Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia | + | + | + | – | – | Verumontanum |

Seminal vesicles/ejaculatory ducts | – | + | + | – | – | Seminal vesicles |

Cowper gland | – | + | + | – | – | Urogenital diaphragm |

Paraganglion | – | – | –/± | +/− | – | Base > apex |

♦

PSA and PAP are patchy positive

♦

S-100 protein and chromogranin are often positive

Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia

Clinical

♦

Occurs in the transition zone and is found in ~23% of prostatectomy specimens

♦

Multicentric in ~46% of cases

♦

Proposed as a putative precursor lesion, but considered by most to be benign

♦

The extent and zonal distribution of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) and carcinoma share a weak but significant association

♦

Shares less frequent but similar allelic imbalance with prostatic adenocarcinoma

♦

May be associated with a subset of low-grade carcinoma arising in the transition zone

♦

The identification of AAH should not influence or dictate therapeutic decisions

Microscopic

♦

Requires most or all of the focus to be present for diagnosis of AAH on biopsy – very uncommon (Table 38.4)

Table 38.4

Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia vs. Well-differentiated Adenocarcinoma

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia | Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

Architectural and associated features | ||

Low power | Circumscribed or limited infiltration | Circumscribed or limited infiltration |

Lesion size | Variable | Variable |

Gland size | Variable | Less variable |

Gland shape | Variable | Less variable |

Crystalloids | Infrequent (16%) | Frequent (75%) |

Corpora amylacea | Frequent (32%) | Infrequent (13%) |

Basophilic mucin | Infrequent | Frequent |

Nuclear features | ||

Nuclear size variation | Less variable | Variable |

Chromatin | Uniform/granular | Uniform or variable |

Parachromatin clearing | Infrequent | Frequent |

Nucleoli | Inconspicuous | Prominent |

Nucleoli (largest) | 2.5 mm (rare) | 3.0 mm |

Nucleoli (mean) | <1.0 mm | 1.8 mm |

Nucleoli > 1 mm | 18% | 77% |

Basal cell layer | ||

Hematoxylin and eosin stain | Inconspicuous | Absent |

Antikeratin stain (high molecular weight 34βE12) | Fragmented | Virtually absent |

♦

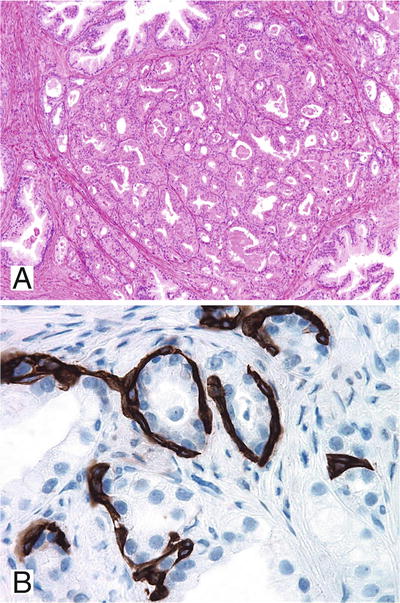

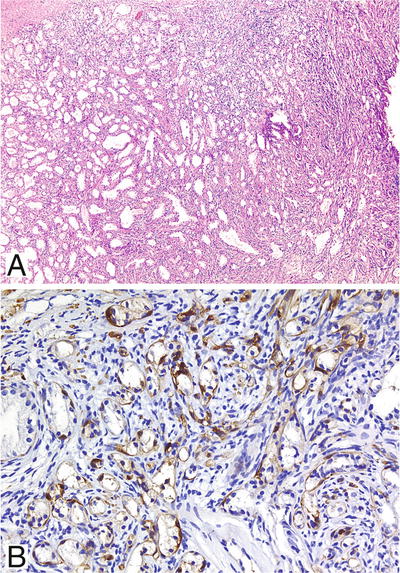

Well-circumscribed nodular proliferation of small acini at the periphery of BPH; sometimes involves the entire nodule (Fig. 38.12A)

Fig. 38.12.

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH). This circumscribed cluster of small to intermediate acini was initially misdiagnosed as Gleason pattern 1 + 1 carcinoma (A); however, a fragmented basal cell layer was identified by immunostain for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 (B).

♦

Parent gland with larger branching lumina in the central location

♦

Lacks diffuse nucleolar enlargement

♦

May contain intraluminal mucin secretions and crystalloids

♦

α-Methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S) immunostaining may be focally positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia:

Located in the posterior wall of the distal prostatic urethra

Back-to-back arrangement of small acini with prominent corpora amylacea

Fragmented nonlamellated orange-red concretions

Cytoplasmic lipofuscin

Intact basal cell layer and intimately associated with urothelial-lined ducts

♦

Postatrophic hyperplasia

Lobular cluster of atrophic acini with proliferative change

Not intimately associated with nodular hyperplasia

Associated with adjacent atrophy with inflammation, stromal fibrosis, or smooth muscle atrophy

♦

Sclerosing adenosis:

Biphasic pattern with hyalinized periacinar stroma

S-100 protein and actin positive

♦

Low-grade small acinar prostatic adenocarcinoma

Nucleolar enlargement

Lacks basal cell layer

Postatrophic Hyperplasia

♦

Occurs in all zones with predilection for the peripheral zone (91% of cases)

♦

Found in up to 32% of radical prostatectomy specimens

♦

Lobular cluster of atrophic acini surrounding central dilated larger acini, often in a hyalinized stroma (Fig. 38.13)

Fig. 38.13.

Postatrophic hyperplasia. Irregular circumscribed aggregate of markedly atrophic distorted acini set in a fibrous stroma.

♦

Variable acinar architectural distortion and irregularity

♦

Acini lined by a single layer of secretory cells with proliferative changes

♦

Moderate cytoplasm with luminal apocrine blebs

♦

Enlarged nuclei with evenly distributed fine granular chromatin and occasional enlarged nucleoli

♦

Fragmented or intact basal cell layer

♦

Often associated with adjacent inflammation

♦

Distinguished from carcinoma by characteristic lobular architecture, intact or fragmented basal cell layer, inconspicuous or mildly enlarged nucleoli, and adjacent acinar atrophy with stromal fibrosis or smooth muscle atrophy

Sclerosing Adenosis

Clinical

♦

Incidental finding in 2% of transurethral resection specimens

♦

An unusual variant of BPH

♦

Occurs in transition zone, usually solitary and microscopic

♦

The only prostatic lesion with myoepithelial differentiation of basal cells

♦

Benign

Microscopic

♦

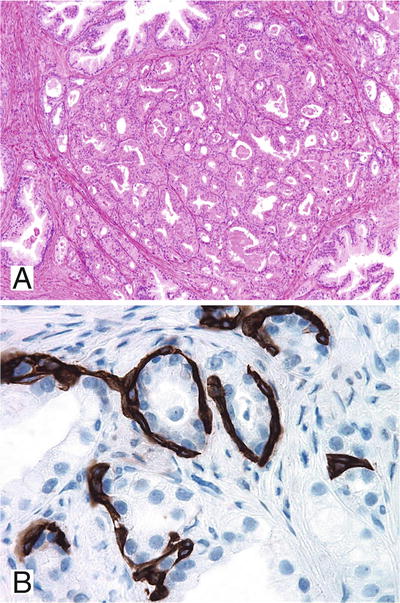

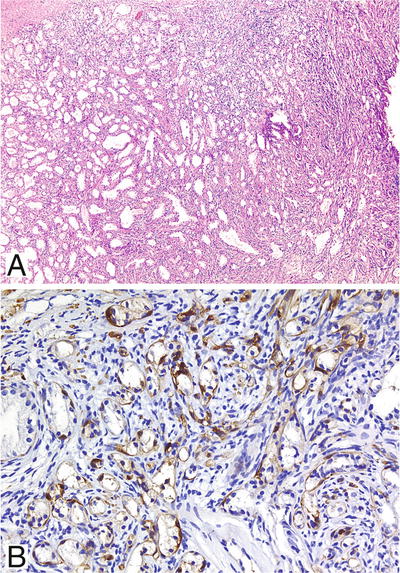

Well-circumscribed proliferation of small acini in a dense myofibroblast stroma (Fig. 38.14A)

Fig. 38.14.

Sclerosing adenosis. (A) Packed circumscribed cluster of small acini of variable size set in a densely cellular stroma. (B) Intense S-100 protein immunoreactivity in the basal cells of virtually every acinus.

♦

Thickened basement membrane with prominent myoepithelial cells

♦

Acini appear to merge with adjacent pale staining cellular stroma with abundant loose ground substance

♦

Compressed and distorted glands imparting a pseudoinfiltrative pattern

♦

Occasional nuclear and nucleolar enlargement; rare cases with prominent nucleolomegaly referred to as atypical sclerosing adenosis

♦

Moderate amount of clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm

Electron Microscopy

♦

Myoepithelial differentiation with aggregates of thin filaments

Immunohistochemistry (Table 38.3)

♦

High-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 and p63 positive

♦

Muscle-specific actin (MSA) positive

♦

Negative for α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

AAH

Lacks densely hyalinized stroma and fragmented basal cell layer

MSA and S-100 protein negative

♦

Prostatic adenocarcinoma

Cytologic atypia with nucleomegaly and prominent nucleoli

Lacks hyalinized stroma

MSA, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, and S-100 protein negative

Hyperplasia of Mesonephric Remnants (Florid Mesonephric Hyperplasia)

♦

Rare; occurs in all zones, mainly in the transition zone

♦

Lobular proliferation of small acini lined by single layer of cuboidal cells (Fig. 38.15)

Fig. 38.15.

Mesonephric remnants.

♦

Two growth patterns:

Closely packed small round to oval tubules lined by cuboidal hobnail cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm

Proliferation of small acini with empty lumens or solid nests

♦

May have haphazard arrangement at periphery, imparting pseudoinfiltrative growth pattern

♦

Ectatic tubules with luminal colloid-like eosinophilic inclusions and micropapillary infoldings

♦

Uniform cells with occasional nuclear and nucleolar enlargement

♦

PSA and PAP negative; high-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 and p63 positive

Verumontanum Mucosal Gland Hyperplasia

♦

Located in the posterior wall of the midprostatic urethra

♦

Used as a landmark during transurethral resection of the prostate (resection is proximal)

♦

Recognized in 14% of radical prostatectomy specimens

♦

Rare in biopsies and not seen in transurethral resection specimens

♦

Often intimately associated with urothelium

♦

Multifocal lobular proliferation of closely packed small (>25) acini usually with intact basal cell layer (Fig. 38.16)

Fig. 38.16.

Verumontanum mucosal gland hyperplasia.

♦

Uniform cells with basophilic cytoplasm and lack of cytologic atypia

♦

Numerous corpora amylacea and distinctive orange-red nonlaminated concretions that are often fragmented

♦

Luminal secretory cells may contain lipofuscin pigment

♦

Intact basal cell layer

♦

PSA, PAP, p63, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 positive

Metaplasia (Table 38.5)

Table 38.5.

Metaplastic Changes of the Prostate

Diagnosis | Features |

|---|---|

Squamous metaplasia | Intraductal aggregates of flattened cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, usually at edge of infarcts |

Mucinous metaplasia | Mucin-producing columnar or goblet cells in the prostate epithelium or urothelium |

Eosinophilic metaplasia | Small clusters of cells with prominent cytoplasmic eosinophilic changes |

Urothelial metaplasia | Urothelium within ducts and acini of the prostate; difficult to identify because of variable location of the normal urothelial-columnar junction |

Nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia) | Inflamed papillary mass of cystic or solid tubules in the urethra; rare |

Squamous Metaplasia

♦

Often seen at edge of prostatic infarct and after hormonal therapy or cryotherapy (Fig. 38.17)

Fig. 38.17.

Squamous metaplasia of benign epithelium following cryosurgery.

♦

Common in the region of prostatic urethra in patients with an indwelling catheter

♦

Syncytial aggregates of polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei

Mucinous Metaplasia

♦

Clusters of columnar cells or goblet cells with mucin production (Fig. 38.18)

Fig. 38.18.

Mucinous metaplasia.

♦

Focal or complete involvement of acini and lack of involvement of the entire lobular unit of acini

♦

Negative immunostaining for PSA and PAP

♦

High-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 positive

♦

Mucicarmine, PAS with diastase, and alcian blue positive

Eosinophilic Metaplasia

♦

May represent a form of host response related to regenerative/reparative process

♦

Clusters of cells with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules in apical location (Fig. 38.19)

Fig. 38.19.

Eosinophilic metaplasia.

♦

Typically occur in small- to medium-sized prostatic ducts and may also occur in the acinar epithelium

♦

No clinical significance

Urothelial Metaplasia

♦

The presence of urothelium beyond the normal urothelial-columnar junction is often difficult to identify

♦

Stratified epithelium with streaming effect of nuclei (Fig. 38.20)

Fig. 38.20.

Urothelial metaplasia .

♦

Ovoid cells with pale cytoplasm, uniform nuclei, nuclear grooves, perinuclear halos, fine granular chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli

♦

The long axis of the cells is perpendicular to the basement membrane

Nephrogenic Adenoma

♦

Suburethral location; composed of exophytic mass of small tubules or papillae with solid and cystic appearance (Fig. 38.21)

Fig. 38.21.

Nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia).

♦

Uniform nuclei with fine granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli; rare cases have focal or extensive nucleolomegaly, referred to as atypical nephrogenic metaplasia

♦

Edematous and often inflamed stroma without desmoplasia

♦

Often associated with proliferative papillary urethritis

♦

Negative immunoreactivity for PSA, PAP, and CEA

♦

High-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 positive

♦

Positive staining for α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (P504S) (58% of cases) creates potential for misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma

♦

May be neither metaplastic nor neoplastic in nature; nephrogenic metaplasia in renal transplant recipients is apparent

♦

Derived from tubular cells of the transplant and is not a metaplastic proliferation of the recipient’s bladder urothelium

Atrophy

♦

Often located in the peripheral zone

♦

Lobular configuration of atrophic glands with open ectatic lumina in a sclerotic stroma

♦

Variable acinar architectural distortion and irregularity

♦

Cystic dilation of acini and ducts lined by flattened attenuated epithelial cells with scant cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli

♦

When associated with inflammation, the epithelium may show focal reactive proliferative changes

♦

The basal cell layer may be fragmented

♦

In the past, considered by some to be a potential precursor to adenocarcinoma, but convincing evidence is lacking and idea is largely abandoned

Seminal Vesicles and Ejaculatory Ducts

Microscopic

♦

Well circumscribed

♦

Complex papillary folds with irregular convoluted lumens (Fig. 38.22)

Fig. 38.22.

Seminal vesicle . The epithelium contains scattered refractile golden-brown pigment, as well as moderate anisonucleosis.

♦

Lined by nonciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium

♦

Ejaculatory ducts have large lumens with more prominent mucosal folding and prominent circumferential layer of the muscular wall

♦

Stromal (eosinophilic) hyaline bodies:

Often seen within the muscular wall, resulting from smooth muscle degeneration

Highlighted by Masson trichrome and PAS stain

♦

Bizarre smudged cells with granular refractile golden-yellow lipofuscin pigment

♦

Enlarged nuclei with nuclear hyperchromasia, coarse granular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and occasional nuclear halos

♦

Multinucleated giant cells with pyknotic nuclei and a lack of mitotic figures

♦

DNA aneuploid in 6.7% of seminal vesicles

Immunohistochemistry

♦

PSA and PAP negative; high-molecular-weight cytokeratin 34βE12 and p63 positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Pigmented prostatic epithelium (melanosis):

Scant, finely granular, yellow-brown pigment

PSA and PAP positive

♦

Postatrophic hyperplasia:

Lobular arrangement of acini surrounding central dilated acini; proliferative change

Lacks lipofuscin or cytologic atypia

♦

High-grade PIN:

Lacks lipofuscin; displays significant nuclear pleomorphism

♦

Adenocarcinoma:

Lacks lipofuscin; displays nuclear degeneration; bizarre nuclei uncommon

PSA and PAP positive, cytokeratin 34βE12 negative

Senile Seminal Vesicle Amyloidosis

Clinical

♦

Occurs in up to 8% of men 46–60 years, 23% between ages 61 and 75 years, and 40% >75 years

♦

Derived from secretory protein of the epithelium

♦

Benign; not associated with systemic amyloidosis

Microscopic

♦

Linear or nodular subepithelial deposition of amorphous eosinophilic amyloid (Fig. 38.23)

Fig. 38.23.

Senile seminal vesicle amyloidosis.

♦

Basement membrane thickening

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Congo red, crystal violet, toluidine blue, and PAS positive

Cowper Glands

Microscopic

♦

Located within the urogenital diaphragm; seen in biopsies of the apex

♦

Not present in transurethral resection specimens

♦

Equivalent to Bartholin glands of the female genital tract

♦

Small paired bulbomembranous urethral glands surrounded by the skeletal muscle

♦

Uniform cells with abundant apical mucinous cytoplasm

♦

Lack nuclear and nucleolar enlargement

Immunohistochemistry

♦

PSA negative; high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, mucicarmine, and PAS with diastase positive

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Mucinous metaplasia:

Focal involvement of a small number of acini

Lacks skeletal muscle

♦

Mucinous adenocarcinoma:

Nests and clusters of epithelial cells floating in extravasated mucin pool

♦

Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma:

Prominent nucleoli

PSA positive, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin negative

Paraganglia

♦

Located closer to the base than the apex of the prostate

♦

Usually associated with neurovascular structures

♦

Solid nests and organoid arrangement of closely packed polygonal cells with abundant clear cytoplasm (Fig. 38.25)

Fig. 38.25.

Intraprostate ganglionic tissue. In contrast with the benign acini (lower right), the ganglion cells are small, closely packed, and contain a light dusting of brown pigment. This focus was initially misdiagnosed as adenocarcinoma.

♦

Centrally located uniform nuclei with or without prominent nucleoli

♦

PSA, PAP, and cytokeratin negative; neuroendocrine markers positive

Prostatic Urethral Polyp

Proliferative Papillary Urethritis

♦

Papillary proliferation of the urothelium with metaplastic changes and reactive changes

♦

Inflammation and stromal edema

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue (Benign Polyp with Prostatic-Type Epithelium)

♦

Adolescents or young adults present with hematuria

♦

Delicate papillae with fibrovascular core and prostatic epithelial lining

Nephrogenic Adenoma

♦

Described elsewhere

Benign Urothelial Papilloma

♦

Patient <50 years with solitary lesion <2 cm in greatest dimension

♦

<7 cells in thickness with intact superficial (umbrella) cell layer

♦

No significant cytologic atypia (no more than grade 1 urothelial carcinoma)

Inverted Papilloma

♦

Patients present with hematuria and urinary obstructive symptoms

♦

Smooth contoured invaginated cords and columns of urothelial cells with intact overlying urothelium

♦

Peripheral palisading basaloid cells and thickened basement membrane

♦

Squamous metaplasia and microcystic change

♦

Scant stroma

♦

Lacks fibrovascular cores

High-Grade Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (HGPIN)

Definition

♦

Precancerous end of the morphologic continuum of cellular proliferations within preexisting prostatic ducts, ductules, and acini

Clinical

♦

Divided into low grade (formerly PIN 1) and high grade (formerly PIN 2 and 3)

♦

Most pathologists do not report low-grade PIN, recognizing the difficulty in separating this lesion from benign epithelium and reactive atypia

♦

PIN is genotypically and phenotypically linked to cancer

♦

Precedes the onset of carcinoma by 5–10 years

♦

Multifocal (63% of cases) and coexists with cancer in 86% of prostatectomy specimens

♦

Occurs in the nontransition zone (63% of cases) and all zones (36%)

♦

Present in up to 4.2% of transurethral resection specimens (2.8% without cancer, 10.2% with cancer)

♦

The volume of HGPIN increases with the pathologic stage, Gleason grade, and positive surgical margins in patients with prostate cancer

♦

More prevalent and extensive and occurs approximately a decade earlier in African American men than in Caucasian men

♦

Prevalence and extent of HGPIN are decreased after androgen deprivation therapy

♦

No influence on serum PSA concentration

♦

Found in approximately 9% of contemporary needle biopsies

♦

The diagnosis of HGPIN confers a 33% predictive value for cancer on repeat biopsy within 1 year

♦

Multifocal HGPIN has an even higher predicate value for cancer than unifocal HGPIN on biopsy

♦

Followup is suggested, but the interval may be 1 year or more according to some; there are no standards, and most agree that multifocal or extensive PIN requires earlier followup

Patterns of Growth

♦

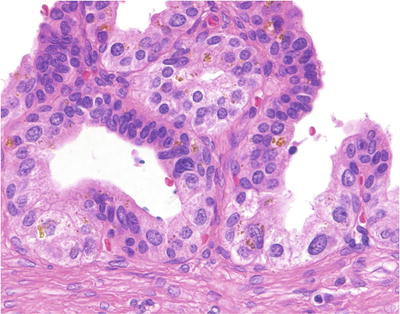

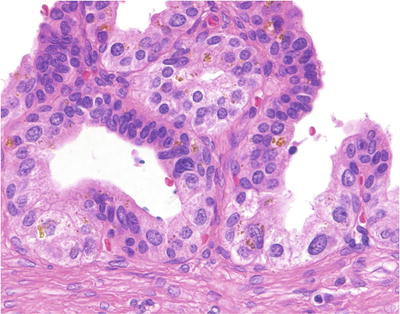

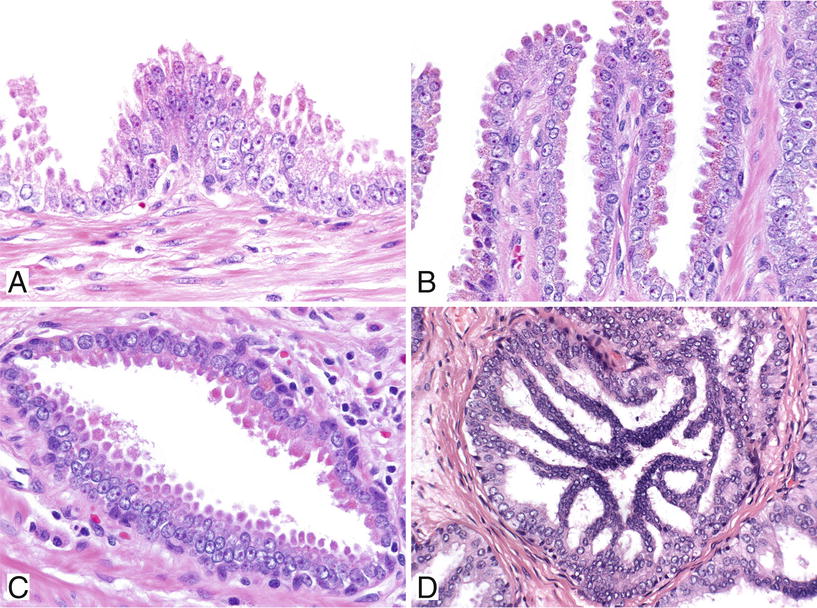

Tufting (97% of specimens with HGPIN, most common) (Fig. 38.26A)

Fig. 38.26.

Four major patterns of high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Tufting pattern of high-grade PIN (A). Small mounds of cells protrude into the lumen. This focus has a prominent basal cell layer at the periphery. Micropapillary pattern of high-grade PIN (B). Elongated fingerlike projections of epithelium protrude into the lumens. Flat pattern of high-grade PIN (C). Cribriform pattern of high-grade PIN (D).

♦

Other rare growth patterns include signet ring cell, small cell (neuroendocrine), foamy gland (microvacuolated), hobnail (inverted), and squamous patterns

Pattern of Spread

♦

Replacement of normal luminal secretory cells with preservation of the basal cell layer

♦

Direct invasion with disruption of the basal cell layer

♦

Pagetoid spread (rare)

Microscopic

♦

Nuclear and nucleolar enlargements are the cytologic hallmark of HGPIN

♦

Cellular crowding, irregular spacing, nuclear stratification, and overlapping

♦

No significant expansion of ductules (unlike intraductal carcinoma; see below)

♦

Partial acinar involvement is frequent