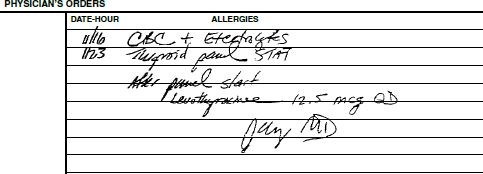

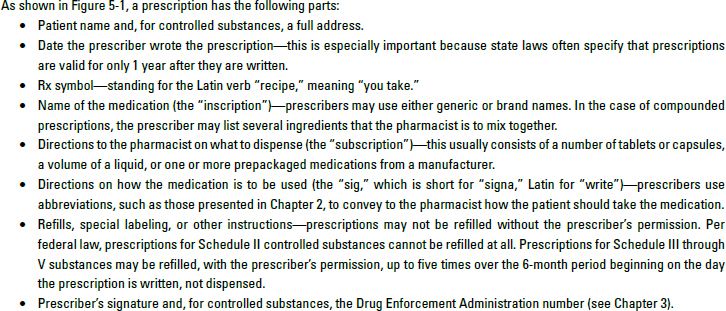

Because the hospital or institution already has information about patients and prescribers on file, medication orders may not have all of the information usually contained in a prescription, as listed in Table 5-1. In the institutional setting, orders for Schedule II substances do not have to be separated and stored any differently from other medication orders, as nurses keep those medications in a locked cabinet or automated device on the patient care unit. Additionally, medication orders may come with special timing instructions, such as “PRN” for medications ordered on an “as needed” basis, or “STAT” orders, requiring medication to be filled within a short time frame (e.g., 15 minutes) in an institutional setting.

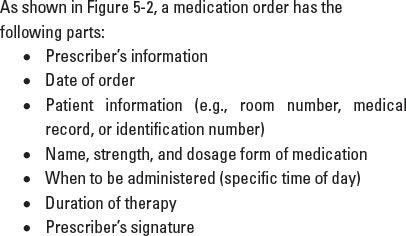

The figure does not show patient information, which would appear in the chart. This medication order represents what a technician would see in “real life.”

Obtaining Information from Patients and Professionals

When information is missing from prescriptions or medication orders, you may need to talk with the patient, pharmacist, or prescriber. Although Chapter 8 discusses communication strategies with patients in more detail, a few general communication points are appropriate to present now.

Any contact you as a technician have with the patient or prescriber should be within the guidelines established by your institution, pharmacy, or supervising pharmacist. Patients have a right to privacy with respect to their health, and you must take care as to when and how you talk with them. In most pharmacies, technicians assist in clarifying the spelling of patients’ names or getting their addresses, but be sure you know what other information you are responsible for obtaining.

Similarly, contact you have with the prescriber should be within the guidelines of your pharmacy or employer. Pharmacists may prefer—or even be required by law—to contact the prescriber directly about unclear critical information, such as the name of the drug or instructions on how to use it, whether a dose is correct, or whether the patient is allergic to a drug. In particular, if you think a prescription may be forged, be certain to work with the pharmacist in contacting the prescriber to verify it (see Chapter 3 for more information about forged prescriptions).

Most pharmacies regularly record patients’ ages because this information is sometimes needed in checking medication doses. In an institution, pharmacists likely obtain this information from patients’ medical records or computer profiles. However, such sensitive information may not be so readily available in a community pharmacy. The best method of asking about age is as a part of a written questionnaire that community pharmacists often have patients complete when they have their first prescription filled. If you need to ask patients for their age or for other personal information such as weight, be sure that you do so in a quiet and respectful manner. You never want to offend a patient or embarrass someone in front of his or her friends and neighbors.

Another type of information you may need to collect concerns the patient’s insurance or health coverage. Again, because this is confidential information, take care to obtain it in an appropriate manner. Errors in the beneficiaries’ names, policy numbers, and other information can cause claims to be rejected, so record this information carefully. To be sure you can hear the patient, insurance and health coverage information is best collected in a quiet area.

Entering Prescriptions or Medication Orders into the Computer

Once you receive a prescription or medication order, the next step in many cases is to put this information into the pharmacy computer system. “Order entry” is the process of entering new prescriptions or medication orders into an existing patient profile or record or creating a new patient profile. Keep in mind that order entry may be accomplished by the prescribing physician or the pharmacist on the patient-care unit in some institutions, or by prescribers using electronic prescribing systems. See Chapter 7 for more information on pharmacy computer systems, patient profiles, and electronic health records.

If you are entering a prescription or medication order, make sure to verify the patient’s name, medical record, or other identification number. Depending on whether you are entering a prescription or medication order, you will need to enter the date, drug name, dosage form, dispensing quantity, directions for use, and number of refills. If the patient has an existing profile or medical record, be sure to confirm that the patient information on the order matches that in the patient profile. If it does not, you will need to create a new profile. Compare the new order or prescription with the patient’s profile. Stay alert for medication duplication, drug class duplication, or other potential problems. Notify the pharmacist if you detect an issue. Problems that may require a pharmacist’s intervention include a potential adverse drug event, suspected drug nonadherence, or suspected drug interaction or duplication.

To avoid medication errors, be sure to read the name of the drug (and all other information) very carefully on the prescription or medication order. Many mistakes in pharmacy occur as a result of illegible instructions from prescribers or misreading of drug names by pharmacy personnel. If the name of the drug does not fit the directions for use (for instance, wrong number of doses per day or wrong route of administration) or if you are not 100% certain of what the prescriber has written, you or the pharmacist must contact the prescriber to clarify the name of the drug. It is not enough to guess about the drug by asking the patient “what they went to the doctor for.”

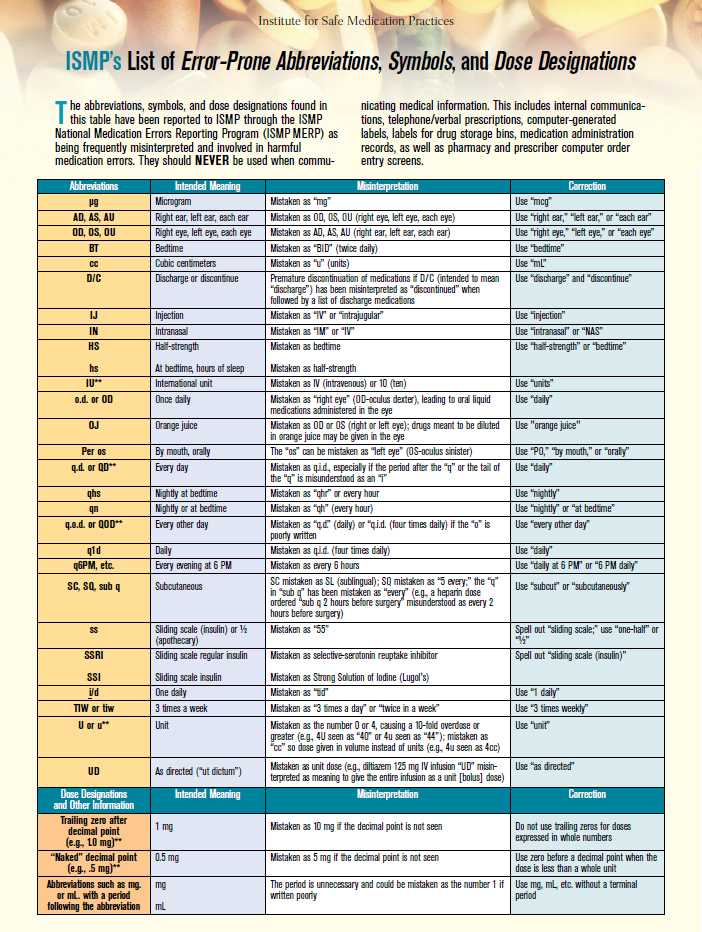

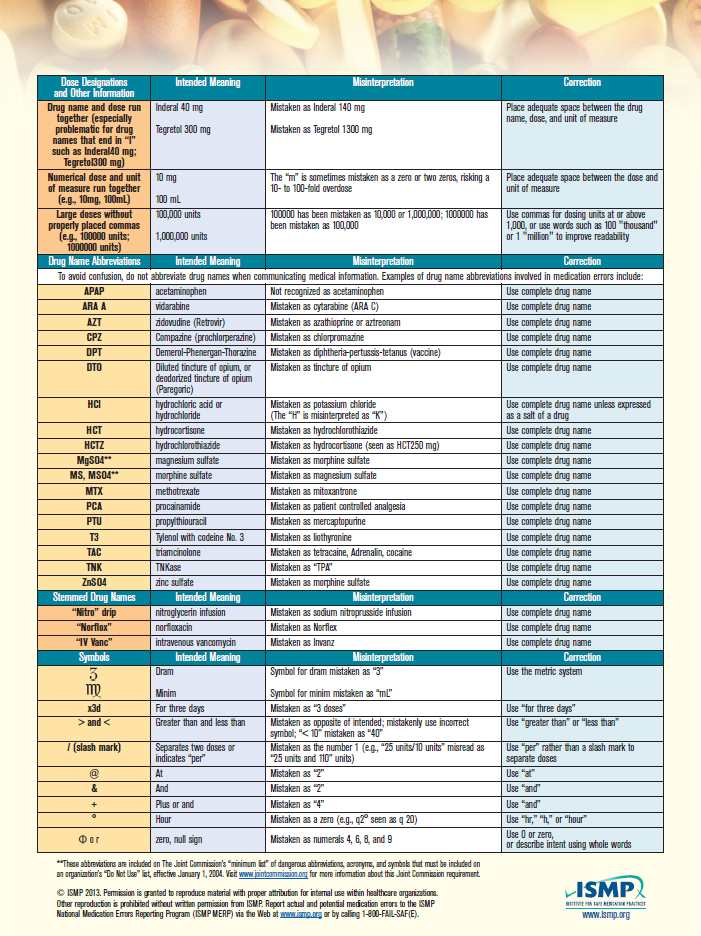

Medication errors may also result from the use of abbreviations that are easily misinterpreted. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) maintains a list of error-prone abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations (Figure 5-3). Organizations accredited by The Joint Commission (TJC) must maintain a “Do Not Use” list of abbreviations to help promote safe communication. ISMP recommends avoiding the use of error-prone abbreviations on all types of pharmacy communications, including written telephone/verbal prescriptions, computer-generated labels, labels for drug storage bins, and medication administration records, as well as pharmacy and prescriber computer order entry screens.1

Also watch closely for drug-utilization review (DUR) or drug-utilization evaluation (DUE) warnings. These alerts warn pharmacy technicians and pharmacists about potential medication issues or problems, such as drug–drug interactions. An alert may appear when a prescription or medication order is entered, processed, or submitted electronically to a third party for billing. Let the pharmacist know if an alert pops up to help ensure patients are using medications safely and appropriately.

Source: Used with permission from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Report medication errors or near misses to the ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program (ISMP MERP) at 1-800-FAIL-SAF(E) or online at www.ismp.org.

Order entry may also be the first point at which a technician or pharmacist is alerted to a potential prescription forgery. See Chapter 3 for more information on fraudulent prescriptions.

Processing Prescriptions and Medication Orders

Once you have obtained all necessary information and you are satisfied that the prescription or medication order should be filled, you are ready to prepare the medication for the patient. The act of transferring a medication to the patient is central to the entire practice of pharmacy. It is that act for which the entire system and profession exist. When done correctly, patients obtain needed medication safely; an error in this system, though, can lead to patient harm or adverse events. Your assistance in this medication-use process constitutes a heavy responsibility that you must take very seriously.

An old adage in pharmacy is that in dispensing medications, you must get the right drug in the right dosage form to the right patient at the right time, labeled with the right directions and other instructions. Let’s look at the process of making sure all these things happen correctly and avoiding medication errors while doing so.

Understanding Generic and Brand Names

Every bit of information on a prescription or medication order is important, but certainly the most important element is the name of the drug or drug product. As mentioned in Chapters 3 and 4, drugs may be prescribed by their generic and brand names, and generic drugs can generally be substituted for their brand counterparts if the two products are classified as being therapeutically equivalent. The generic name is the common name assigned to that chemical compound by the US Adopted Names Council; it may be used by any company that markets the drug. The brand name is a trademarked reference to the drug that only one company is entitled to use. This company is usually the innovator, or original creator, of that drug. Until its patent on the drug expires, the innovator is the only company entitled to market the drug. When a drug is available from only one company, it is called single-source product. For example, Prevacid, shown in Figure 5-4, was a single-source product until the innovator’s patent expired. When a drug is available from more than one company, it is called a multisource product. Notice in Figure 5-5 that all the products have the same generic name, glipizide, but the innovator product also has a trade name, Glucotrol. Occasionally generic products also have a brand name; these are called branded generics, but they are still essentially just generic alternatives to the originator branded product.

In a community or ambulatory pharmacy, if a prescription is written for a brand-name drug but other (usually cheaper) generic products are available, you must follow the laws in your state concerning generic substitution (Figure 5-6). In several states, you must inform the patient of the availability of the lower-cost agents and let the patient decide which product he or she wants. If the prescriber has written “Brand Product Necessary” on the prescription or checked a box for “Dispense As Written,” you must follow the prescriber’s instructions and give the patient the brand-name product. In an inpatient setting, many institutions have a limited “formulary” or a predetermined list of preferred drugs that can be dispensed in that institution. In this setting, the therapeutic substitution is often automatic in the institutional pharmacy and formulary restrictions are communicated to prescribers and pharmacists in an ongoing manner. Talk with the pharmacists you work with about how to handle these situations in your pharmacy and your state.

This photo shows the innovator product (Glucotrol) and generic alternatives.

Depending on state laws, prescriber directions, patient preferences, and facts about bioequivalence as determined by the US Food and Drug Administration, the pharmacist may or may not want to substitute a generic alternative for the prescribed brand of medication.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree