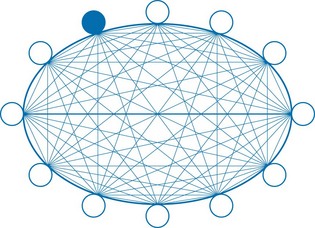

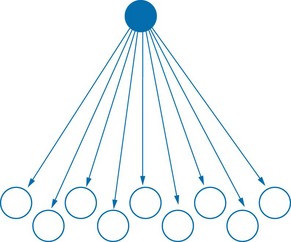

Chapter 20 Problem-based learning (PBL), now widely adopted in medical programmes internationally, was developed at McMaster University Medical School over 40 years ago. PBL has proved to be effective in promoting active learning, collaboration, communication skills and critical thinking. The principles of PBL have been applied in a variety of other health-related programmes (Dangerfield et al 2009). The term ‘PBL’ means different things in different medical schools, and the diversity of approaches can be represented as a continuum (Harden & Davis 1998). The defining characteristic is that a small group of students is presented with a problem to solve and a structured approach to solving it. The design varies greatly among institutions and with the students’ experience or seniority. A problem usually centres on the clinical presentation of one or a few patients (e.g. an individual with Parkinsonism, a child with a metabolic disorder and the child’s parents, or a couple presenting with infertility). The problem is usually introduced as an illustrated description of a realistic clinical presentation, but sometimes PBL is conducted in clinical settings with real patients. PBL often starts with a vignette summarizing the clinical presentation. At first, students do not have sufficient knowledge to proceed easily: they are deliberately confronted with a problem they cannot solve. By working collectively, they identify key elements and seek out additional information, enabling them to suggest causal hypotheses and identify possible pathophysiological mechanisms. At the start, students are encouraged to think broadly about alternative hypotheses, mechanisms and the sociocultural context. They then refine and test their hypotheses in order to arrive at the most likely explanation. Thus, students are supported as they learn about multiple dimensions of a topic in medicine, greatly enriching and diversifying their learning experiences, especially when they can link PBL to other learning (Dangerfield et al 2009). PBL is an example of active learning. In contrast to rote learning and memorization, active learning involves interaction, pursuing information, collaborative problem-solving, sharing of ideas, evolving and testing hypotheses. The group collectively gains skills and finds solutions. Thus PBL models effective medical teamwork and communication. Students agree to follow up on specific issues individually or in groups, identifying and sharing information with colleagues. The success of PBL is attributed to the opportunities that it creates to activate and elaborate knowledge in the group situation (Schmidt et al 2011). The specific roles of tutors vary among medical schools. In general, the tutor’s role is to facilitate, encourage active learning and promote collaboration on relevant ideas and concepts. Tutors are trained: they do not impart information or provide ready answers. In a well-functioning group, students themselves actively identify issues, share information and seek clarity on difficult concepts (Woods 1994). Tutors are usually expected to adapt their approach to the level of the students’ learning, the quality of the PBL group’s interactions and the nature of the current problem. Tutors often differ markedly in their backgrounds, qualifications, experience and styles of interaction. The need to select only medically trained tutors is often debated, and recruitment of medical teachers from a range of disciplines is recommended (Norman 2011). Students generally prefer medical graduates as tutors, provided that they respect the need to facilitate group learning, avoiding domination and didacticism. Tutors are not expected to be content experts. Rather, they should have a level of knowledge sufficient to keep the discussion focused and to identify gaps and errors in covering the topic. Tutors need to ensure that students understand and can summarize key issues. The problem or case can be introduced in different ways. If a real patient is the subject of a PBL, the process may begin with a short summary of his or her clinical presentation. If the problem is based on a hypothetical patient, the process begins with a trigger statement that briefly summarizes the characteristics, clinical presentation and circumstances (Box 20.1). The trigger statement may be read out by a student or the tutor, played from a recording or presented as a photograph or computer image to encourage observation. Typically, a recording of the trigger statement is played from a computer while a digital image is shown on the screen. The students examine the trigger statement and image, identifying ‘cues’ about the case. Students collectively observe and interpret the images that provide the context. They contribute ideas, suggesting and noting relevant information, and then identifying issues to be explored. Group members typically take turns acting as scribe, summarizing ideas on a whiteboard, a computer or paper (Visschers-Pleijers et al 2006). In an effective tutorial, a lively exchange of information and ideas ensues as students identify issues and explore possible mechanisms. The desirable form of the interaction within a PBL group is depicted in Fig. 20.1. Effective tutors avoid taking a traditional didactic teaching role, such as that depicted in Fig. 20.2. The original PBL design assumed that, after a tutorial, students would locate and identify useful information to bring back to the next session, thereby progressing to resolve the problem. However, in recent years, the widespread use of portable computers and handheld devices, with immediate access to published literature and other information sources, has compressed the task of inquiry. Members of PBL groups now find information almost instantaneously during a session, bringing it into the discussion without delay. This is a potentially valuable addition to the learning opportunities of PBL, provided that students’ interactions with their computers do not weaken the group interaction. It is important, however, that students do not fall into the habit of uncritically accepting information from electronic sources that are not critically reviewed.

Problem-based learning

Introduction

What is PBL?

Key features and strengths of PBL

Roles, qualifications and training of PBL tutors

Introduction of PBL problems

Problem-based learning