OVERVIEW

- Listen to the patient

- Consider the possibility of medically unexplained symptoms (MUS)—think about epidemiology and about what is common in particular age groups

- Look for typical clinical features—of both organic disorders and functional (MUS) syndromes

- Target the examination and investigations

- Give a constructive explanation

- Link the explanation to action—either specific or generic

- Set appropriate expectations and safety nets

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to describe the principles behind identifying, assessing, labelling and managing MUS. These principles will be covered specifically in each of the symptom-specific chapters.

Listening to the patient

As in any field of medicine, eliciting a good patient history is essential in dealing with patients with MUS. Key to this is letting the patient tell their own story as clearly as possible and with the minimum of interruption in the initial stages.

Most patients will have a clear account of their illness in their head as they enter the consulting room. Often it will more or less correspond to the commonsense model of illness. This means the patient will already have considered features such as condition name (or diagnosis), potential causes, timeline, and the likely outcome or treatment. The more you let the patient tell you this for the first one or two minutes of the consultation (using active listening and simple encouragement) the less you will have to get from them later.

As you move to direct questions to clarify what the patient has said, consider getting the patient to describe the experience of the symptom before you pin them down to specifics of time, place or relationship to other things. Table 6.1 illustrates the difference between asking a patient about the nature and the experience of a symptom.

Table 6.1 Difference between asking a patient about the nature and the experience of a symptom.

| Describing the nature | Describing the experience |

| Doctor: What’s the pain like? Patient: It’s a dull ache Doctor: And when does it come on? Patient: It’s really there all the time | Doctor: So, what does the pain feel like? Patient: Well it’s usually a dull ache, but sometimes it becomes unbearable, you know, as if my back is going to give way Doctor: And is there a particular time or place? Patient: I can usually bear it but I worry when I’m holding my grand-daughter I’ll drop her |

Notice how the experience of a symptom, elicited with the ‘what does it feel like’ question can includes emotional or consequential components of the symptom whereas a description of the nature of the symptom is much simpler. Both are of equal value in making a disease diagnosis, but the experiential account gives you greater insight into patient ideas, concerns and expectations without needing to ask additional questions.

Asking when the symptoms first began, or when they were worst, can reveal clues to the diagnosis but there is a need to be careful. A stressful time will increase awareness of anything out of the ordinary including symptoms of serious disease. Furthermore, the patient has control over how they answer this and if a symptom did begin at a stressful time, the patient may wish to disguise this, in case the doctor jumps to conclusions.

You will want to know about patients’ ideas, concerns and expectations. Several chapters in this book describe this, but none suggests you bluntly ask ‘so what do you think is causing this?’ If the patient does not volunteer this—as in the example above—then listen to what the patient is asking you for. If they suggest an explanation, then that is most likely what they want. If they suggest an investigation, then you need to discuss that. Although patients offer cues about what they want, most doctors overestimate patients’ wishes for investigation, resulting in unnecessary tests that patients neither want nor need. If you do feel the need to ask patients directly about ideas, concerns and expectations then try not to make it confrontational—maybe ask ‘so how do you make sense of all these symptoms?’ as they are crossing the room to the examination couch. Do not leave it to the end of the consultation, you should have all the information you need before then.

Considering the possibility of MUS

Remember that around one in six patients in a GP clinic will be consulting about symptoms that are not associated with disease. However, it is important to remember also that although most MUS occur in infrequent attenders and do not lead to repeat consultations, around 2% of the population do consult repeatedly with MUS and your records should give you a clue to this. Have they had referrals that resulted in ‘no evidence of disease’ or one or more symptom syndrome diagnoses such as IBS? Have they had repeated negative investigations, such as thyroid function tests for palpitations and for fatigue? Have they previously been diagnosed with panic disorder (or been seen with panic attacks)?

Look for typical features of organic and functional conditions

Each of the symptom-based chapters in this book aims to point out positive diagnostic features of MUS. MUS do not have to be diagnoses of exclusion (although some exclusion of other things may be necessary); they should be positively sought and assessed. Check also for the important red flags. Unexplained weight loss, night sweats, abnormal bleeding are all signs of disease and not of MUS.

Target your examination and investigations

You do not have time for a detailed examination of everything for every patient so focus. For headaches, check the blood pressure and examine the optic discs. Feel the painful abdomen, listen to the anxious heart. Not to do so diminishes your ability to reassure the patient and help them towards recovery. Remember also that clinical thoroughness and competence is what patients value more than anything else (including prompt appointments and nice doctors).

Whatever body system you are examining there are some important things you can do to add value to your focused examination.

- Be positive about your examination. Avoid the throwaway line of ‘let me take a quick look’. An anxious or concerned patient wants a thorough examination. ‘Let me take a careful look at this’. ‘Good’, ‘thorough’, ‘proper’ are all useful adjectives for an examination.

- Explain what you are doing. Try to get into the habit of talking patients through some of your examination. This can either be before (‘now I want to check there are no swollen glands’) or after (‘and everything about your abdomen feels normal’). There is no need to describe everything, but some feedback is important and you can target it to areas of specific concern for that patient.

- Report something rather than nothing. ‘I’ve carefully felt your abdomen and there is no sign of any swelling or blockage’ is more helpful than ‘I can’t feel anything’. Again if you listen for patients’ concerns before the examination you can address them directly as you examine.

- Point out and explain ‘inconsistencies’. Signs such as Hoover’s sign (see Chapter 13) or the skin pinch were originally designed to trap patients, however if you demonstrate them, you can use them constructively. If a skin pinch or light touch generates pain (allodynia) then explain how that indicates that the nerves are sending pain signals up to the brain from several healthy areas and not just from one (abnormal) area.

Give constructive explanations

This is probably the thing doctors do least well for patients with MUS. Most explanations given by doctors are either dismissive ‘it’s nothing serious’, or normalising ‘it’s just a bit of wear and tear’, ‘it’s probably a virus or something’. Some are collusive—‘so, you wonder if you have ME [myalgic encephalomyelitis], well I suppose you might have’ and some just bark up the wrong tree ‘It’s fine, no sign of cancer’—in a patient who wondered whether helicobacter might be causing his dyspepsia.

Constructive explanations have three characteristics: they are plausible and acceptable, they do not imply blame, and they lead to something therapeutic. In addition they should be memorable—a good test is to see if you can summarise the explanation in one or two sentences. If you cannot, then the first time someone asks your patient what you said, you can be certain they will struggle.

Giving constructive explanations is not easy. In addition to the examples in this book, many condition-specific websites have thought long and hard how to describe a condition, so it is worth looking these up. If you wish to make your own explanations then keep them fairly concrete (rather than allegorical) and mechanistic—because that is the way that most people view their body. Spending some time looking up, writing and rehearsing the explanations you give to patients would be a worthwhile piece of reflective practice to include in your appraisal or revalidation portfolio.

Link the explanation to action

In a simple, ‘explained’ condition, this is easy. ‘You have a chest infection, I’m going to prescribe antibiotics for you to take’. In a complicated unexplained condition this is not always so simple. But, as Chapters 15 to 17 clearly demonstrate, whether treatment is cognitive, behavioural or pharmacological, explanation—sometimes with negotiation—is essential. It is illogical to take an antidepressant for physical pain in the pelvis. On the other hand, if the pain is due to nerve circuits that start from the ovaries and surrounding area and are not working properly, then using something to restore these and rebuild the pain barrier makes a lot of sense. Without a constructive explanation, treatment is much less likely to happen. Sometimes the action may be nothing more than a commitment to support the person while they tackle the difficulties you have both identified.

Set appropriate expectations and safety nets

There are two sets of expectations here. Expectations for the symptoms and patients’ expectations of you. Both are important.

Expectation of recovery

Most MUS go away. Many go away quite quickly, some take a while, but most resolve. That means that in most cases you can reasonably create an expectation of improvement or recovery. Expectation is one of the key components of the therapeutic effect of consulting a doctor (which underpins the placebo effect) and works in two ways. The first is by converting pessimism to optimism ‘The doctor said it will settle’—but that does not last. A second, cognitive, component relates to interpreting change in a positive way. ‘She said that to start with there would be the odd good day, and then with time I would start to see more of them. That’s happening now so it looks as if I’m on the road to recovery’. Telling patients what you expect of treatment is important for this. But remember that this works the other way too—as discussion of the nocebo effect in Chapter 17 demonstrates.

Expectation of you

Some patients will expect an investigation or referral. If this is their first episode of a new and potentially significant symptom this may be appropriate. If you are not going to investigate then it is important to explain why in a positive way. ‘I’m not going to refer you for a scan of your spine because my examination shows there are no nerves trapped and a scan can’t show which nerves are giving you pain’ is better than ‘because it will probably be normal’. A few patients will keep requesting investigation or referral, although this is fairly uncommon. In this case you need to have a discussion about what they hope to gain, what they have gained in the past, and why a different way of looking at the problem—based on function rather than structure—is needed. Sometimes pointing out that scans and other tests are ‘snapshots’ of a system and can never show if something is intact but not working properly can be helpful.

Many patients will hope that you can give them a bit of support as they struggle through a difficult patch. That may be little more than an occasional review, checking that things are stable and some empathic recognition that they are doing OK all things considered. Some patients will be more demanding and for these you may need to set limits. No doctor can fix everybody and a few patients with MUS also have severe personality disorders. GPs in particular sometimes feel a sense of failure if the doctor–patient relationship is not as good as they expect. If that is the case discuss it with a colleague and consider transferring the patient to the care of a different doctor. If all you are doing in consultations is maintaining the doctor–patient relationship you are not working effectively.

Setting safety nets

The idea of safety netting is well established in medical training and has already been mentioned in Chapter 3. Remember though that a small proportion of patients with apparent MUS have an unrecognised physical disease. It makes sense to review patients at appropriate intervals but at least as important as reviewing is looking out for—and using—new information. It is perfectly reasonable to include both expectation of recovery with a safety net. ‘I expect this will settle over the next few weeks, but if it doesn’t, or if X happens, then come back and see me’.

Bringing it all together

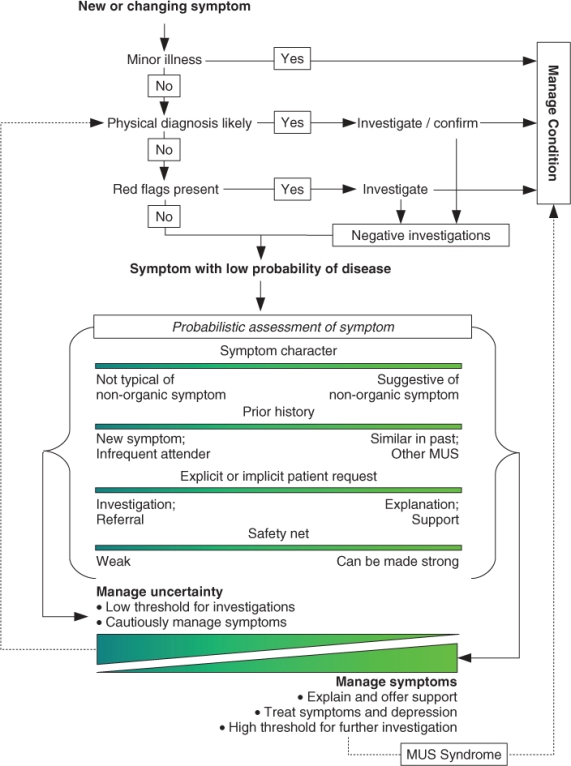

This chapter has outlined a set of principles for managing patient with MUS and illustrated these with examples of generic skills and techniques. These will be applied to specific contexts in Chapters 7 to 13, but for now are summarised in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Two-stage model evaluating and managing physical symptoms. MUS, medically unexplained symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree