INTRODUCTION

Dr Jones knocked on the exam room door, where her last patient of the day awaited her. “Enter,” a voice said within. She did and found Mr White assembling his medication bottles on the desk to his right. Dr Jones met Mr White 7 years ago when she was an internal medicine resident rotating on the inpatient cardiology service. She became his primary care physician after that first hospitalization, but until recently, she rarely felt that she added any value to his well-being.

“How are you today, Mr White?” she asked, sitting next to him at the desk. “I am happy to report that I have just one concern!” he replied. He looked well. His bare ankles were slim, not swollen, and he spoke without needing to take a breath between every couple of words—a vast improvement from prior visits.

In the early days of their relationship, Mr White had spent nearly as much time in the hospital as he did at home. His heart failure and its episodic exacerbations were his identity: swollen legs and shortness of breath tethered him to a hospital bed when he missed a day’s pills or ate too much salt. Dr Jones tried desperately to help him, but years of rushed visits and occasional phone calls did little to keep him out of the hospital. The helplessness she had felt frustrated her and her colleagues; most chose to become specialists rather than stay in primary care.

The frustrations ended when Dr Jones’ clinic went through a transformation. Inspired by a new model of primary care—the “patient-centered medical home”—the clinic management reorganized the practice to facilitate team-based care, better access, and more contact with patients between visits. The days of delivering care through 15-minute appointments spaced out over months were over. Dr Jones and her team—a nurse, medical assistant, and clerk—began meeting weekly to figure out the best way to improve the well-being of the entire group of patients assigned to her team.

Mr White was a special case, given how often he was hospitalized. The team decided that he needed weekly phone calls from someone with time to ensure that he knew exactly how to take each of his medications and their purpose. Malik, the team’s medical assistant who was also trained as a “health coach,” used protected time each week to call Mr White. Each week, they would discuss Mr White’s symptoms, medications, and anything else that came up. Within weeks, the intervention was successful: Mr White was able to adhere to his diet and medications and no longer required stints in the hospital. Malik calls Mr White weekly to this day.

“Well then,” Dr Jones said, “Let’s spend this visit discussing what matters to you.”

Robust primary care is critical to any healthcare system delivering high-value care. In systems with greater numbers of primary care providers, the outcomes are better: lower rates of hospitalization, better patient experience, and lower overall costs.1 Unfortunately, the predominant US payment structure does not reward some of the most important work done in primary care, including thoughtful diagnosis, listening, counseling, and coordination of care. Too often Dr Jones and her colleagues must fit more patients into their schedule each day—propagating the cycle of burnout and fewer trainees choosing primary care careers.

Fortunately, hope for the future of primary care exists. A handful of practices across the United States have transformed using team-based care, patient- centeredness, and local partnerships with payers to fund innovations and feedback population-level data.2 Spreading these innovations to all components of the US healthcare system is the difficult task ahead—one that will require systemic changes (such as new reimbursement methods), as well as new models of clinical care. In order to staff these new innovative practices, new forms of training will be necessary. The primary care provider of the near future will be able to care for a population of patients, not only through face-to-face visits, but also via e-mail, phone calls, and participation on a team.

WHY IS PRIMARY CARE CRITICAL TO DELIVERING VALUE?

Primary care serves as the foundation of high-value healthcare systems in most wealthy nations of the world, as well as in specific communities within the United States. However, when it comes to the overall makeup of the US healthcare system, it seems that primary care stands as an afterthought despite its proven benefits.1 According to the late health policy expert, Barbara Starfield, robust primary care must be composed of four pillars: first-contact care, continuity of care over time, comprehensiveness (addressing all aspects of patients’ care needs rather than focusing only on a specific organ system), and coordination of care with other parts of the health system (Figure 9-1).3 Each pillar not only defines primary care but also is critical for this domain of healthcare to deliver value.

First-contact care requires that primary care be ideally delivered where patients first access the healthcare system. Unfortunately, in the United States, a growing number of people are not able to obtain timely appointments to primary care and instead go to the emergency department (ED)—which is much more expensive. From 1997 to 2007 in the United States, the number of ED visits increased by 23%, and ED visits for Medicaid patients increased by 84%.4 Dr Stephen Pitts and colleagues from Emory University found that two-thirds of ED visits were made after-hours or during the weekends.5 This is unsurprising given that only 29% of primary care practices in the United States see patients after-hours, compared to 89% of practices in the United Kingdom, and 97% of practices in the Netherlands.6 Not providing timely access to care counteracts much of the value that primary care offers: catching disease processes early and preventing costly ED visits and hospitalizations. One study estimates nearly half of ED visits could be prevented with timely access to primary care.7

Continuity of care refers to maintaining a relationship with the same provider or team over time. Most patients appreciate greater continuity of care: it is associated with higher patient satisfaction with their providers and outpatient visits, especially for the most vulnerable patients.8 Providers also value continuity of care.9 In addition to its effects on overall patient and provider satisfaction, continuity of care leads to better outcomes, including improved delivery of preventive care, fewer hospitalizations, reduced costs, and lower overall mortality.10,11 However, continuity of care requires both an adequate supply of providers as well as an organized system of care delivery, two attributes the US healthcare system currently lacks.

Comprehensiveness of care requires that primary care be capable of addressing the wide scope of issues that affect patients and families. Robust primary care should reduce the need for referral to specialists, but the reality is quite the opposite: providers in the United States are more likely to refer to specialists than other wealthy countries.12 In turn, nearly half of visits to specialists in the United States are for routine follow-up and preventive care services that could have been performed by primary care providers.13 This is problematic because of the higher cost of these visits and the greater tendency of specialists to order expensive tests, procedures, and medications. In one study, cardiologists were more likely than generalists to prescribe brand-name medications when generic formulations were available.14

Coordination of care means primary care takes responsibility for managing patients’ health needs through the full spectrum of settings where care is delivered. For example, primary care coordinates transitions of care, such as when a patient moves from the hospital to their home or from their home to a long-term care facility, communicating with the variety of specialists and other personnel involved in the patient’s care. In an international survey of patients with complex care needs, patients in the United States who had a primary care provider reported some of the best care coordination. Unfortunately, in the United States, those patients with complex care needs—who could most benefit from care coordination—were least likely to report having a regular primary care provider.15

Health systems built on a robust foundation of primary care that demonstrate the four pillars have been consistently shown to deliver higher value care overall. Medicare beneficiaries residing in areas with more full-time equivalent primary care physicians per capita had lower all-cause mortality, lower rates of preventable hospitalizations, and lower Medicare spending.16 In a study of US metropolitan areas, regions with higher ratios of primary care physicians to specialists had lower total utilization of healthcare services.17 Given this evidence, calls abound to increase the capacity of primary care systems in the United States to deliver the type of first-contact, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated services that have been associated with such high-value care. However, efforts to revitalize US primary care face a number of challenges that have been mounting for decades: a growing demand for primary care services, a worsening primary care workforce shortage, and a reimbursement system that does not value primary care services.

THE SUPPLY/DEMAND MISMATCH

The demand for primary care in the United States has been steadily increasing over the years and is forecasted to accelerate largely due to an aging population with an increasingly complex set of care needs.18 Even prior to insurance expansion brought on by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (see Chapter 2), the demand for primary care was expected to surge, particularly in rural and underserved areas that already face considerable shortages in primary care capacity—workload could increase by 29% between 2005 and 2025.19 Demand for primary care will likely be further heightened as both public and private healthcare purchasers demand more proactive and preventive services for employees and beneficiaries to avoid utilization of more costly downstream health services.20

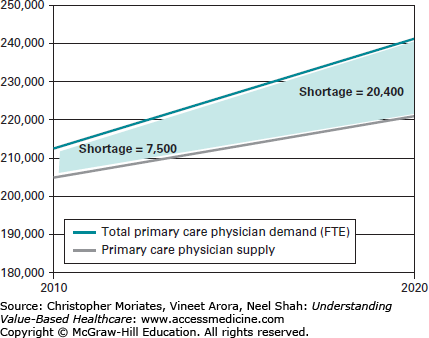

How many primary care providers will it take to serve these growing care needs? Estimates vary greatly but share two common features. First, the estimates focus on primary care physician services rather than nonphysician providers, given that physicians constitute over three-fourths of the primary care currently delivered in the United States.21 Second, the estimates warn that demand for primary care services will soon far outstrip supply, leaving the United States with significant shortages of primary care, especially given the health insurance expansion of the ACA. Recent estimates of this developing shortage range from a need for 20,000 to 50,000 primary care physicians over the next decade (Figure 9-2).21-23 Despite increasing calls for policy solutions to account for the potential for nonphysician members of the primary care workforce to help fix the projected shortages, almost all policy proposals assume that physicians will continue to supply the vast majority of primary care services in the United States for the foreseeable future.

Figure 9-2

The primary care shortage.

Notes: Data are from Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services. National demand projections assume that in 2010 the national supply of primary care physicians was adequate except for the approximately 7500 FTEs needed to de-designate the primary care HPSAs.

In growing numbers, individual providers are retiring early or switching to part-time work. Reasons for this trend are greater care demands on providers’ plates, enhanced time pressures, chaotic work environments, and increasing regulatory requirements.24 Moreover, the workforce is aging. One-third of current primary care physicians will reach retirement age within the next decade.25

Burnout is experienced by up to half of primary care physicians, a disproportionately high rate compared to specialists.26 By 2016, the number of adult primary care physicians leaving the workforce will exceed the number of physicians entering the workforce—making the burden on existing and incoming primary care providers even greater.18

Given the rate of departure from the profession, expanding the workforce will depend on more students choosing a primary care career. Unfortunately, graduates of US medical schools have been increasingly unlikely to do so, with less than 20% of them opting to choose primary care careers, nearly a 25% drop since the 1980s.27 Reasons for the decline include a culture of primary care “bad-mouthing” at many medical schools, dissatisfaction with primary care clinical experiences where students regularly observe burnout among both attendings and residents, and the “hidden curriculum” that glorifies specialty careers and hospital-based health services.28-30 An even greater influence may be the remarkably lower financial return on investment of choosing a primary care career—specialists’ salaries are 267% that of primary care providers.31 When coupled to the average educational debt of $160,000 to $200,000 among graduating medical students, physicians will usually opt for careers with higher salaries.32

The resulting shortage of primary care services is unequally distributed around the nation, with rural and urban underserved communities facing disproportionately higher levels of shortages.33 Despite increasing investments in federally qualified health centers, physicians rarely choose to practice in this setting. Between 2006 and 2008, less than 5% of residency graduates went to practice in underserved communities.34 With federal health insurance expansion under the ACA, the supply-demand mismatch will worsen—after state law expanded health insurance in Massachusetts, the number of patients receiving care at community health centers increased by 31% while the number of primary care clinicians remained steady.35

What will it take to create an expanded reinvigorated primary care workforce? Given the aforementioned primary care provider-specialist income gap, efforts to revitalize the pipeline that do not involve substantial payment reform have little chance of success. According to the Council on Graduate Medical Education, an advisory group authorized by congress to make recommendations to the Department of Health and Human Services, primary care salaries will need to be at least 70% that of specialists in order to entice graduating medical students to pursue primary care careers.27 In addition to increasing primary care salaries, efforts have been made to increase loan forgiveness for trainees choosing primary careers, specifically in underserved areas. The National Health Service Corps offers loan forgiveness and salary supplementation for primary care providers, and due to new investments from the ACA and the Recovery Act, the number of National Health Service Corps providers has tripled since 2008.36

Changes at the medical school level will also be needed, such as admissions policy changes that prioritize student characteristics associated with greater levels of eventual primary care practice and service in underserved communities.31,37,38 Given publicly funded medical schools’ greater tendency to graduate students into both primary care and service to underserved communities, efforts to expand US medical school capacity should prioritize funding to public programs.37 The Title VII program of Section 747 legislation authorized Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) to award grants aimed at improving the quality of primary care training in medical schools and residency programs.39 Even though the program has been successful in encouraging trainees to pursue generalist careers, legislators often threaten to decrease its funding.39

Additionally, it will be critical for this next generation of primary care physicians to have skills and competencies aligned with the components of transformed practice.40 A number of residency programs are supplementing clinical competencies with communication, quality improvement, and practice-based learning skills integral to team-based care.41 However, given that funding for residency programs flows through hospitals, outpatient training receives less emphasis than inpatient training, often resulting in graduates that are poorly trained for outpatient practice.42 Additionally, the outpatient clinics in which residents practice primary care are usually subpar, specifically in the domain of continuity of care, compared to other clinic models, which further discourages graduates from choosing primary care careers.43,44 The solution to the workforce problem, therefore, will involve reforming the way residency programs are funded to encourage more outpatient training and improving the actual care delivered by resident-based clinics to prepare trainees to work in transformed primary care practices.

An example of the latter is learning collaboratives.45 Mirroring the efforts of quality improvement experts in nonacademic settings, the collaboratives are a space to accelerate transformation in care delivery and provider training among participating practices. One example is the “I3 collaborative,” first launched in 2003 to improve chronic disease management among 10 academic primary care practices. Early on, the collaborative resulted in a nearly fourfold reduction in congestive heart failure (“CHF”) hospitalizations through sharing best practices and optimizing the roles of nonprovider team members; since then, the collaborative doubled in size and has since taken on a variety of other quality improvement and cost control initiatives.46,47 The model has spread to collaboratives in Colorado, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania.48-50

Revitalizing primary care will require more than just addressing the shortage of physicians—these efforts must coexist with efforts to recruit nonphysician providers to primary care. Primary care delivered through teams, including nonphysician providers, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and medical assistants, could alleviate the projected provider shortage, but would require liberalized scope-of-practice laws and payment reform to compensate nonphysician services.51 If preventive and chronic care services are shared with nonprovider members of the primary care team, each practice could care for larger numbers of people, ensuring linkage to primary care for a greater percentage of the population.52

Ultimately, as much as the increasing engagement of a diverse set of health professionals on the primary care team represents glimmers of hope to the looming primary care service shortage in this nation, transforming the primary care team poses profound challenges. First, the traditional, siloed approach to health professions training—where different professions spend little time interacting during their training—does not support the new model. Second, new care teams will produce other unforeseen inefficiencies and costs associated with coordinating information and care between an increasingly large team. Third, the model causes concern that the physician will be increasingly relegated to a background role, separated from patients by a layer of other health professionals. We do not know what this will mean for patient satisfaction, the doctor-patient relationship, patient safety, and trainees’ interest in primary care careers. What we do know is that the current model of primary care delivery is untenable.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) provide disproportionate degrees of primary care services to minority populations, particularly in underserved and rural populations.53 Because of their lower average salaries, shorter length of training, and greater ability to shift specialties mid-career, NPs and PAs seem like one workforce solution to the primary care shortage.54 Yet, just like the trend in graduating physicians, less and less of these professionals are entering primary care careers: one-half of NPs and one-third of PAs currently practice primary care.21,54 Wide-ranging scope of practice laws and reimbursement policies also limit what nonphysician providers can do and get paid for doing.55 For example, some states allow NPs to practice independently from physicians while other states require that physicians directly supervise NPs at least a portion of the time.56 In Missouri, each time an NP sees a new patient, a physician must see the patient within 2 weeks of that first visit.56

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree