Learning Objectives

- Understand the definitions of primary care and primary health care

- Understand the development of primary care historically and its global importance today

- Understand the role of primary care in health systems and how countries with inadequate primary health care are adversely affected

- Be able to compare and contrast four countries with different health policies, priorities, and resources

Introduction

Primary health care is a phrase introduced to our lexicon in the 1970s. It is, however, an approach to health care that in fact has been present for centuries. It is important for us to understand the roots of primary health care in general practice as well as its current practice to fully understand its role in society and health. It is also important to distinguish between primary health care, as a comprehensive strategy for health promotion, and primary care, typically representing the element of clinical service delivery in that broader strategy toward health.1

Health care has become a major issue for many countries in the 21st century. Health care includes economic, social, political, and technical issues. The questions that surround national debates regarding health care around the globe are similar. How do we best promote health and treat disease? Who should provide this care? How should the system be organized? What is the right balance and mix of health providers, and how should they be distributed? What health services should be provided for all, and who should pay? How much should health care cost? For individuals and families, the core question can be synthesized as follows: How do I attain the highest possible level of health, and how do I best access health services in times of need?

This chapter focuses on primary health care and how it is organized and practiced around the globe. It offers a definition of primary care and looks at how it is delivered in the context of a comprehensive primary health care strategy among different health care systems. It explains how primary care can have an impact on disease and on health indicators. It looks at what some goals could be for improving health systems through advocacy for primary care education and delivery and discusses health workforce issues as they relate to models for training of primary care physicians and other members of primary care teams. The chapter focuses on primary care physicians because of the limitation of space; however, we recognize there are many other health professionals who often compose the primary care team.

Additionally, the chapter explores how four countries with vastly different political and socioeconomic conditions have tried to improve health in their countries—some through the advent of strong primary health care delivery systems, others through systems traditionally based on specialist care, and others who have selected primary health care as the central theme for health care reform and are in the early years of implementation. It is hoped that you will gain an appreciation for the complex challenges involved in improving opportunities for health for all.

The History of Primary Care

Healing has been practiced for centuries around the globe. In fact, in the premodern era it was practiced in broadly similar ways. The healer was often an elder of the community who over time had gained respect and knowledge. Disease was believed to come from both natural and supernatural causes. Often the causes were felt to be spiritual, involving the entry or exit of spirits to or from the body. Primary care has its roots in the premodern era when healers had strong ties within communities and used this status to improve the health of the members of the community. Over time some of these healers became known as physicians, the person who “heals or exerts a healing influence.”2 Others became nurses, midwives, pharmacists, and allied health professionals, among others. Traditional healers continue to provide health advice and treatment worldwide as well.

Over time, the art of healing was joined with the science of prevention. The Yellow Emperor, the first sovereign of civilized China, wrote the Neijing roughly 2,000 years ago, which has come to be known as The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine.

In the good old days the sages treated disease by preventing illness before it began, just as the good government of emperor was able to take the necessary steps to avert war. Treating illness after it has begun is like suppressing revolt after it has broken out.

A superior doctor arrests disease at the skin level and dispels it before it penetrates deeper. An inferior doctor treats illness after it passes the skin.

A good healer cannot depend on skill alone. He must also have the correct attitude, sincerity, compassion, and a sense of responsibility.3

Hippocrates later articulated the importance of a holistic approach to health. In Plato’s Phaedrus we learn that “Hippocrates the Asclepiad says that the nature even of the body can only be understood as a whole,”4 and “it is more important to know what sort of person has a disease than to know what sort of disease a person has.”5

The Renaissance brought the beginning of modern medicine in 1543 with the publication of the first complete textbook of human anatomy, De Humanis Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius. Vesalius was a classicist by education. He knew Greek and Latin and had studied the ancient writings and extolled them. He was considered a true humanist; in his teachings, he was able to blend the approach to the whole person with his science. The evolution of the physician as scientist and humanist continued.6

The ensuing three centuries brought many changes in the science of medicine. Alongside progress in medical science most of the world continued to use traditional healers. In countries that were becoming industrialized through the 19th and early 20th century, however, physicians and nurses assumed the primary responsibility for patient care. Before the political changes of 1917 in the Soviet Union, there was a rich tradition of general practice. The Zemstvo physicians combined traditional medical care with the humanitarianism and reformism of the contemporary populist movement. These physicians believed that if medical care was to be effective, it had to be given in tandem with improvements in the sanitation, nutrition, and living standards of the time.7

In the United States, the generalist was also the primary physician. This was advocated by William Osler in an article entitled “Internal Medicine as a Vocation” published in the Medical News in 1897: “By all means, if possible, let [the young physician] be a pluralist, and—as he values his future life—let him not get early entangled in the meshes of specialism.”8

The end of the 19th and early part of the 20th centuries brought with them desires for reform in medical education. The Medical Act of 1858 in Great Britain9 and the 1910 report entitled Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching,10 authored by Abraham Flexner, offered recommendations that would change the face of medical education in these countries and then the world. The activities generated by these reports developed standards for the accreditation of medical schools and policies related to the qualifications of physicians. Although these reforms raised the quality of medical education, they concurrently caused a disproportionate reduction in the number of physicians serving disadvantaged communities.11

The role of the generalist physician continued to evolve during this period. There was a progressive separation of the role of community-based general practitioners from physicians and surgeons who specialized and held hospital appointments. In this division the general practitioner became the doctor of first contact working in the community, whereas consultant physicians and surgeons controlled the hospitals with their scientific and technical facilities. Patients who needed these additional services were referred by their general practitioners.

As medical education reforms evolved through the early part of the 20th century, so did the need for good generalist physicians. In his book, A Time to Heal, Flexner wrote, “The small town needs the best and not the worst doctor procurable. For the country doctor has only himself to rely on: he cannot in every pinch hail specialist, expert, and nurse. On his own skill, knowledge, and resourcefulness, the welfare of his patient altogether depends. The rural district is therefore entitled to the best trained physician that can be induced to go there.”11

In nonindustrialized parts of the world, the value of the generalist health care provider of first contact was also recognized. Barefoot doctors were farmers who obtained basic medical training and worked in rural villages in China to bring health care to areas where urban-trained doctors would not settle. There had been scattered experiments with this concept before 1965, but with Mao’s famous 1965 speech about health care,12 it became institutionalized as part of the Cultural Revolution, which radically diminished the influence of the Weishengbu, China’s health ministry, dominated by Western-trained doctors. In Vietnam, a national Commune Health Center system was created in the 1950s; it was staffed by health care workers initially but then began to receive staffing by generalist physicians in the late 1960s and 1970s.13

Health care professionals of first contact have evolved and become more stratified in response to advances in medical sciences and therapies. Health care services are often organized into four overlapping levels of care: primary care, which is the focus of this chapter; secondary medical care, which includes consultations by specialists for patients with more unusual problems; tertiary care, which is care for patients with disorders that are so uncommon in a population that the primary care physician would not be expected to maintain skills in caring for them; and emergency care, which is initial care for urgent problems or trauma.14

The Definition of Primary Care

In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened a conference in Alma Ata, the capital of the Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan. It was attended by 3,000 participants from 134 governments and 67 international organizations. The purpose of the conference was to look for ways to improve health. Ideas about primary health care had been discussed in many countries and across many organizations. The outcome of this conference was a declaration regarding health and primary health care. The group declared health to be a fundamental human right, called for an attainment of a minimum level of health by the year 2000, and identified primary health care as key to achieving this goal. The declaration provided a framework for the definition of primary health care as essential, practical, affordable, scientifically sound, and the main focus of overall social and economic development. The group recognized needs fulfilled by primary health care will vary depending on the location, burden of illness, demographics, and socioeconomic circumstances of the community.15

In the 21st century, although there has been great progress in various arenas of health, it is now also clear that the goal of Alma Ata remains too distant, with many countries still struggling to adequately meet the health care needs of all people. A variety of issues contribute to this continued health deficit, but it is also recognized that there remains a wide range of commitment to, and subsequent implementation of, primary health care across nations. As a result, in 2008, the WHO renewed the call for development of high-quality primary care throughout the world in their report “Primary Health Care—Now More Than Ever.”16

Traditionally, the terms primary health care and primary care were often used interchangeably, intended mainly to indicate any health improvement effort that principally takes place in the community, as distinct from secondary or tertiary care provided in hospitals. Over the years since Alma Ata, however, the definitions of primary health care and primary care have become more distinct. In today’s lexicon, primary health care typically refers to a broad approach to improving health at both the individual and community level. Primary health care may include public health elements such as nutrition, clean water and sanitation, maternal and child health, family planning, immunizations, mental health services and provision, and essential drugs, as well as community-based individual clinical services.17

In the lexicon of this expansive definition, the meaning of primary care has evolved to refer primarily to the specific element of clinical service delivery such as preventive and curative services for individuals and families provided within the broader context of primary health care. The unique quality of primary care is that it does not focus specifically on the diagnosis and treatment of specific disease processes, but rather it aims for the broader goal of quality health through the provision of health services utilizing principles of care founded in the primary health care approach.

Even with this refined meaning of primary care, the role and specific elements of what constitutes high-quality primary care remains far reaching. In their 2008 report, the WHO outlined that primary care:

- Provides a place where people can bring a wide range of health problems

- Is a hub through which patients are guided through the health system

- Facilitates ongoing relationships between patients and clinicians

- Builds bridges between personal health care and patients’ families and communities

- Opens opportunities for disease prevention, health promotion, and early detection of disease

- Utilizes teams of health professionals with specific and sophisticated biomedical and social skills

- Requires adequate resources and investment but provides better value for money than its alternatives16

Primary care may be provided by public or private practitioners and includes efforts to coordinate services across sectors. In economically developed countries, primary care professionals include family doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and a variety of allied health professionals. In less economically developed countries, primary care may be delivered by health workers who have received shorter courses of training, such as barefoot doctors in China or Aboriginal health workers in Australia, as part of a national strategy to provide improved primary health care. These health workers are often community members and therefore knowledgeable about the communities they serve; they provide a vital link to other health care providers.

As countries work to provide the highest possible level of health care services at the lowest cost, researchers have analyzed how the organization and composition of health services affect health outcomes. There are many determinants of health for individuals and for populations. The basic determinant, of course, is the gene pool, but this is “heavily modified by the social and physical environment, by behaviors that are culturally or socially determined, and by the nature of the health care provided.”18 Across all countries, evidence shows us that health outcomes are often adversely affected by poverty both within and between countries.

Although health care services is one of the wide range of determinants of health outlined at Alma Ata, greater spending on health care does not necessarily improve health outcomes. Very strong evidence exists that access to comprehensive primary health care improves health outcomes. Increasing the ratio of primary care physicians to specialists improves health outcomes even more.19

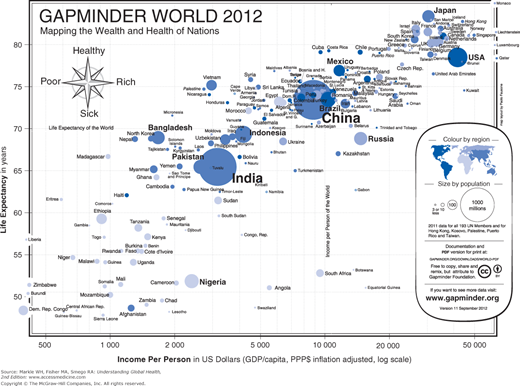

The benefits of primary health care become apparent by reviewing the relationship between primary care orientation and the health indicators of the population. A review of life expectancy reveals general trends in health outcomes across the world, recognizing life expectancy is greatly impacted by infant and child mortality (Figure 8-1).

These data reveal clusters of countries with similar rankings on a logarithmic scale.20 Although efforts toward accomplishing the Millennium Development Goals have resulted in significant improvements over recent years, large disparities remain. Much of Africa, ravaged by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, remains with very low life expectancy and continues to struggle with high child mortality, despite a broad range of income. In Asia, we can see important variations, such as Vietnam’s higher life expectancy compared with China, despite China’s substantially greater income. Among high-income countries, we see the United States sits below its peers in life expectancy despite generally higher income. Economic factors play a significant role in determining health outcomes, but evidence is mounting that development and access to primary health care services play an important role as well.

Data have been analyzed from Western industrialized countries, looking at the strength of primary care as evaluated based on nine characteristics of health systems’ infrastructure (Table 8-1) and six practice characteristics of the patients’ experiences in receiving care (Table 8-2). A scoring system was developed to assign a relative value to the countries studied based on their level of primary care. The countries with higher rankings in primary care were found to have had better health indicators. Additionally, those countries that had weak primary care infrastructures had higher costs and poorer outcomes.14,21

Extent to which the system regulates the distribution of resources throughout the country |

Mode of financing of primary care services |

Modal type of primary care practitioner |

Percentage of active physicians involved in primary care versus those in conventional specialty care |

Ratio of average professional earnings of primary care physicians compared with other specialists |

Requirement for cost sharing by patients |

Requirement for patient lists to identify the community served by practices |

Twenty-four-hour access arrangements |

Strength of academic departments of primary care or general practice |

A correlation also exists between primary care and age-standardized mortality. With a 20% increase in the number of primary care physicians, there is an associated 5% decrease in mortality (40 fewer deaths per 100,000). Most important, the effect is greatest if the increase is in family physicians. One more family physician per 10,000 people (an estimated 33% increase) is associated with 70 fewer deaths per 100,000 (an estimated 9% decrease). In contrast, an estimated 8% increase in the number of specialist physicians is associated with a 2% increase in mortality.22 An association also exists between primary care and infant outcomes. The greater the supply of primary care physicians, the lower the infant mortality and percentage of low-birth-weight infants. An increase of one primary care physician per 10,000 has been associated with a 2.5% reduction in infant mortality and a 3.2% reduction in low birth weight.23

Numerous studies have demonstrated that earlier detection of diseases such as breast cancer,24 melanoma,25 colon cancer,26,27 and cervical cancer28 improves with greater access to primary care. A decrease in total mortality and the mortality for colon cancer, heart disease, and stroke is also correlated with increased access to primary care.29 Increased access to primary care results in better health outcomes and lower costs.30,31

Almost all of the evidence concerning the benefits of primary care systems comes from industrialized countries. There remains little data from developing countries. A study in Indonesia that looked at primary health care and infant mortality rates showed that as the government shifted spending away from primary care and toward the hospital and technological sector, there was a worsening of infant mortality.32

Principles of Primary Care

Essential to delivery of quality primary care services is sufficient training in the core principles of primary care:

- Access or first contact care

- Comprehensiveness

- Continuity

- Coordination

- Prevention

- Family- and community orientation

- Patient-centeredness

Although many of these principles have been taken for granted since evidence to support them was first outlined decades ago, many developing countries lack experience with the implementation of these principles in their health systems and thus require explicit training programs in these principles.

Maximizing the effectiveness of human resources for health also requires more than training. In developed countries and in the wake of the increasing evidence to suggest high-quality primary care offers an opportunity for improved individual and population health at lower costs, there is a renewed interest in health system concepts related to high-quality primary care. It is now being recognized that even in those countries where dedicated training programs in core principles of primary care have been ongoing for some time, broad health system supports are needed to promote practical and uniform implementation of these principles. Standardized evidence-based approaches are being piloted on a wide scale, such as patient-centered medical home initiatives.33-35 As a result, interest in primary care development now goes well beyond training to explore what overall system supports can be implemented at the governmental, societal, and institutional level to promote clinical service delivery that adheres to these core principles of primary care. Although there may need to be a shift in emphasis of specific principles depending on local health system needs, each principle plays an important role in the delivery of primary health care.

Access to health care is increased when primary care services are provided at the community level, usually through primary care team members. Access is determined by availability, convenience, proximity, affordability, and acceptability.18 Of course, barriers to each of these exist in most settings to some degree, and countries may face greater barriers in some aspects than others.

Under ideal circumstances, a usual source of care is identified by the patient representing the point of first contact with the health care system for most health issues. This point of first contact should offer patients continuous access to health care services through coverage arrangements, along with referrals for patients who require services that are not available at the local level. When patients can readily access primary care services in the community, they are less likely to seek hospital services, which are often less convenient and more expensive.36

The principle of comprehensiveness focuses on the concept that the capacity for addressing a wide range of issues is necessary at the point of first-contact care. Patients who typically present to sources of first-contact care are undifferentiated and unfiltered by their very nature, and so a broad range of medical problems may face providers at the grassroots level.18 Providers need to be trained to handle the most common medical problems encountered at their local level, and also be sufficiently skilled in recognizing, managing, and referring more complicated or unusual problems.

Insufficient training in a broad range of problems can quickly lead to dissatisfaction among providers’ ability to provide quality care and result in increased turnover at the primary care level. In addition, the site of first contact needs to have adequate supplies to deal with this broader range of medical issues.

Continuity of care can be present on three levels: informational, longitudinal, and personal.37 Informational continuity refers to the maintenance and communication of medical information about a patient. Core to this concept is the creation and maintenance of a personal medical record that may be kept by the patient, stored at the point of first contact, or maintained electronically. Continuity of information may occur over time from visit to visit, among providers within a single health care facility, and between independent facilities such as the point of first contact and a hospital.

Longitudinal continuity involves health care that is provided over time at a single facility or with a specific health care team. Continuity is expedited when patients can identify a usual source of care, sometimes referred to as a medical home. In response, care is enhanced when a team of providers assumes primary responsibility for promoting the health of a specific group of patients.

Personal continuity involves an ongoing personal relationship between an individual patient and a personal physician or other primary care provider; alternatively, this relationship might include a few select team members in an effort to maintain longitudinal continuity when the personal provider is not available. In this interpersonal relationship, the patient knows the physician by name and develops a basis for trust.37

Continuity is enhanced when patients can identify and readily access their own primary health care providers, but the various barriers to access cited earlier can also negatively impact the various levels of continuity. Furthermore, efforts to overcome these same barriers and provide enhanced access may also at times unintentionally reduce continuity, such as in an effort to offer more convenient and timely care but that occurs when the patient’s personal provider is not available.38,39

Coordination is perhaps one of the most important and universal aspects of primary care. This can mean collaboration among team members, between a range of specialty providers, or simply with the patient and their family. At its essence, coordination of care involves the responsible provider collecting and interpreting all the relevant information and placing it in the context of a specific patient, and then assisting the patient in all aspects of his or her health. This assistance might range from prescribing a medication to provision of relevant immunizations to communication with a specialist or group of specialists focused on a single but more complicated aspect of the patient’s health. Coordination of care is known to improve patient outcomes, making it an effective tool for management and treatment of illness, especially chronic disease.40,41

Coordination can also refer to health management skills, and the need to coordinate a primary health care team. In some primary care systems, doctors may supervise the care provided by nurses, physician assistants, community health workers, and other health team members to ensure continuity of care for a greater number of patients.42 In these situations, doctors typically focus their direct service delivery efforts on the care of patients with more complex conditions while nurses and other health professionals provide preventive services, manage less complex patient problems, and pursue more time-intensive case management activities in chronic disease care.

Prevention is often situated at the intersection between public health and primary care. It is an essential element of primary health care and often responsible for the greatest quantitative improvements in health outcomes.

Primary care is uniquely situated to promote public health–based preventive services at the individual patient level. Primary care can leverage the enhanced access, repeated clinical encounters over time, as well as the interpersonal relationship with a health care provider to encourage adherence to a variety of preventive measures. In many settings, the point of first-contact care is the most logical and effective place to dedicate resources toward disease prevention.43

The orientation of primary care to include family and community is an important principle for maximizing the effectiveness of health care. The focus on family acknowledges the crucial role family members play in health and illness. Engaging family members can help individual patients achieve lifestyle modifications and improved adherence to therapies. Understanding the family situation can put an individual’s medical problems into a more holistic context and identify potential caregivers for assistance when needed.

Community-oriented primary care provides an opportunity for the primary care provider to apply the experiences from their daily clinical service delivery to the public health context.18 It is important for the primary care provider to recognize the influence of the greater community—including social, environmental, and economic impacts—on both the scope of medical problems presenting to their clinic and the approach to health for individual patients. Conversely, through regular interaction with the local population seeking first-contact care, the primary care provider is provided with a vital window on the overall health of the community. The daily diagnoses presenting to the provider can act as a barometer of the overall health of the community. For health systems to take full advantage of this feature of primary care, providers need to be equipped with the skills and procedures to act effectively on their health observations.

In the rush toward improved health outcomes, the need for patient-centeredness can easily be forgotten. Disease-based approaches to improved health are often seen as more likely to provide scientifically proven and statistically significant quantitative improvements in focused health outcome measures. The increased focus on these approaches is compounded when such outcomes need to be demonstrated over a very limited period of time, a common demand of funders in global health improvement efforts. Although the desire for proven improvements in specific health indicators over short funding periods is certainly understandable, these disease-based approaches fail to take into consideration the specific health of individuals. Each individual represents a complex system in itself, typically impacted by an interaction of influences from family, community, and a variety of individual health problems, commingled with an individual patient’s personal life and health goals. A provider equipped to understand the complicated interactions of these determinants of health and identify the most relevant interventions has the potential to bring together a variety of health improvement strategies in a powerful and synergistic way.

Primary care utilizes the principles just outlined to accomplish this synergy and aid patients in achieving their desired level of health. The well-trained primary care provider uses all of these principles to identify the problems and concerns of a patient, build a body of evidence relevant to the patient to support specific diagnoses or management plans, elicit the influencing factors surrounding the patient, and then counsel the patient in a shared decision-making venture toward the patient’s personal goals. In this setting, patient satisfaction enters the equation as both an important health determinant and health indicator.

At times, a patient’s personal goals may not include a maximum level of health—and thus can be at odds with government or funder goals, running contrary to a usual public health approach. It stands to reason that a patient that is not motivated toward maximal health is likely to act as a drag on a variety of population health indicators. By developing health systems that support primary care providers in focusing on the core principles of primary care, however, the grassroots provider has an opportunity to bring a variety of powerful tools to bear on improving every individual’s health to a maximal achievable level. Systems that fail to account for the interaction of individuals’ many health determinants miss an opportunity to maximize effectiveness at best and can unintentionally negatively impact overall patient health at worst.44 In primary care, improved health is achieved while respecting the individual’s specific needs in the context of a health system’s overall goals.

Human Resources for Health

People are at the heart of all effective health systems. Health professionals and their support staff, or human resources for health, organize and provide services and health education and assess outcomes. A wide array of skills is required for the effective delivery of comprehensive primary care services; these services may be delivered by a variety of personnel.