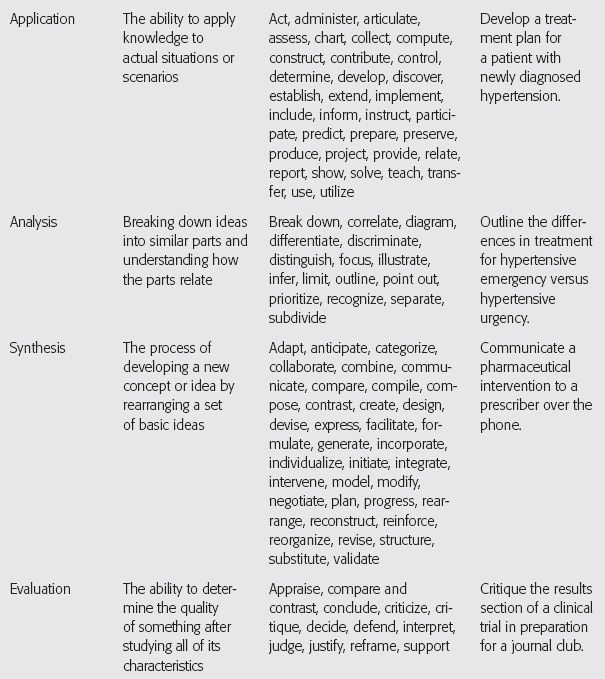

* The list of verbs is not all-inclusive; other verbs may be used to write each type of learning objective.

Source: Ruple JA, Dalton A. Teaching health careers education: Tools for classroom success. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby, Inc.; 2010.

Additionally, you may be asked to submit review questions. Review questions are often required if your lecture will provide CE credit, and you may be required to generate review questions even if your lecture will not provide CE credit. If review questions are required, it will be easy to write them once you have written the learning objectives. The learning objectives will dictate the content of your review questions, and the questions will parallel your objectives. You should be “testing” your audience on the learning objectives. For example, if one of your learning objectives is to “State three barriers to counseling a hearing-impaired patient,” then one of your review questions might be “Which of the following provides a list of barriers to counseling a hearing-impaired patient?” with multiple choice options following. You will not need a question for every learning objective; three to six questions is probably sufficient. However, you should refer to any guidelines you were given or ask the coordinator of grand rounds if you are unsure of how many questions to provide.

Perform Research and Obtain Key References

After you have completed generating the required background materials, it is best to start researching and obtaining key references for your presentation, similar to the manner in which was explained for a topic discussion. Prepare for the grand rounds lecture just as you would for any other formal presentation.

Practice the Presentation

It is essential to practice your presentation. This will help you to discover any issues you may have with the phrasing of certain concepts.16 For example, you might understand the mechanism of a drug in your head as you think about it, but as you explain the mechanism aloud you realize that it is difficult to put it into words. Practicing should also decrease any nervousness and improve your confidence as to the lecture’s content.16

When practicing your lecture, make sure to stand up and speak your presentation aloud. If possible, practice in the room where you will be presenting. You should make sure to use the same visual aids you will be using for your lecture. As you practice, take notes if there are changes you want to make as you go along.

Additionally, time your presentation to ensure that you are within any prespecified time allotment. It is vital to never go over the allotted time frame. However, it is also vital that you use the time you are given. Concluding a 60-minute presentation 5 to 15 minutes early is acceptable and provides time for questions; however, going over by a few minutes may cut into the busy schedule of your listeners.

The Question-and-Answer Period

At the end of your grand rounds presentation, the audience members will have an opportunity to ask questions of you. Follow the same format previously explained in the journal club section of this chapter. As before, remember to repeat any question that is directed at you. This ensures that everyone in the audience can hear the question. It also confirms that you heard the question correctly and gives you a little extra time to formulate the answer in your head. Once there are no more questions from the audience members, be sure to thank your audience for their time and attention.

PHARMACY INSERVICES

The term pharmacy inservice is a broad term used to describe education, whether formal or informal, provided to individuals in the pharmacy department or any other department within a healthcare setting. It is meant to keep the pharmacy and other departments up to date on any pharmacy-related procedural or protocol changes, provide information on new medications added to the formulary, or present any other pharmacy-specific topic that can help other healthcare professionals improve their knowledge and safe use of the medications administered to their patients. Oftentimes, pharmacy personnel provide inservices to the nursing staff, because they are on the front line of medication administration. For example, a pharmacist might provide an inservice about the appropriate timing of insulin administration with respect to meals and the types of insulin to administer before meals.

The following are some tips for giving a successful pharmacy inservice:

• Know your audience. How much does your audience already know about the topic? Do you need to give more background? For example, if you are a pharmacy resident presenting to a group of peers about the aforementioned timing of insulin topic, you would not need to go into much detail about the difference between regular and rapid-acting insulin. However, if you are presenting to a group of nurses, you should be prepared to go into more detail on the different types of insulin, focusing on the onset and duration of action.

• Do your research on the topic. Once your research is complete, review the proposed content or outline of your presentation with a preceptor or another colleague.

• If your topic is about changing a protocol or procedure, know the old protocol and procedure well and be prepared to answer questions as to why a new approach is being implemented.

• Prepare and provide concise handouts. Consider preparing and distributing a pocket card if the inservice is regarding an important topic that the audience would need to refer to on a regular basis. For example, if you are presenting dosing strategies and drug concentration evaluations for intravenous vancomycin to a group of medical residents, a pocket card might be useful.

• Give case examples. Have your audience “walk through” a case or example so they will feel comfortable performing the task in real time.

• Make sure the information is practical and presented in a clear and concise manner.

• Practice your presentation, and then practice it again. Practice until you feel comfortable with the material.

• Be aware of the allotted time you are given so that you can prepare your inservice topic appropriately. Inservices can be as short as 5 to 15 minutes, but may be as long as an hour. Time yourself when practicing to ensure you are within the allotted time frame. Healthcare professionals usually have busy schedules, and you want to be respectful of everyone’s time.

INTERPROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION

Interprofessional communication occurs when healthcare providers from different professions, such as a pharmacist and a physician, communicate with each other.17 Both the American College of Clinical Pharmacy and the Institute of Medicine support the incorporation of more interprofessional education within the various healthcare professions.17,18 Interprofessional education in the classroom will hopefully lead to more effective interprofessional communication in clinical practice. The importance of effective interprofessional communication is evident when a pharmacist is trying to implement a pharmaceutical intervention by collaborating with prescribers. Advances in medical care, and the vast array of knowledge and skills needed to effectively care for a patient, warrant the need for a multidisciplinary approach to patient care.17

Communicating with a Prescriber: Making a Pharmaceutical Intervention

The essence of the knowledge gained during pharmacy school or other educational endeavors is apparent when making a pharmaceutical intervention. Whether the intervention makes a small or large impact, the outcome should be a positive one. By making an intervention, the patient’s health may improve, the risk of adverse effects may decrease, the patient may pay less for an alternate medication, or you may save your pharmacy department money.

A standard script is not available to follow when communicating with a prescriber to make a pharmaceutical intervention, but there are certain things that should be included in the communication. At a minimum, the following components should be included in any communication with a prescriber regarding an intervention: your name and profession (this may not be necessary if speaking face to face and each person knows the other), the name of the patient, the pharmaceutical issue, the proposed resolution, and, before ending the communication, a final decision on how the issue will be resolved. However, Table 10.5 lists a number of factors will affect how a pharmacist approaches an intervention.

The patient care setting will affect how a pharmacist communicates an intervention to the prescriber. For example, interventions made in the community or retail setting are most often done via telephone. Interventions made in the hospital or out-patient clinic setting may also be communicated via telephone, but they are also often discussed face to face with the prescriber.

The level of rapport the pharmacist has established with the prescriber is another factor when making an intervention. For example, if the pharmacist making the intervention has been practicing as a clinical pharmacist for 2 years with a certain prescriber, this prescriber will likely be more willing to accept recommendations from this trusted clinical pharmacist with little question. However, if the intervention is being attempted by a new pharmacy student on the medical team, the prescriber may ask more questions and be more reserved about taking any recommendations until the prescriber has come to trust and respect the student. It may take a student his or her entire clinical rotation to establish this trust; however, if the student is confident and is well-prepared when making a pharmaceutical recommendation, this will help secure the intervention.

TABLE 10.5 Factors that Affect How a Pharmacist Approaches a Pharmaceutical Intervention

• Hospital versus community setting |

• Level of rapport already established with the prescriber |

• Nature of the intervention: Major versus minor change in therapy |

• Experience level of the pharmacist or pharmacy student making the intervention |

• The prescriber’s experience of working with pharmacy personnel to implement interventions |

• Knowledge of the topic/medication that is the core of the intervention |

Similarly, the amount of experience the pharmacist or pharmacy student has when communicating with prescribers will also affect the communication. If the pharmacist or student has had the experience of communicating with prescribers a number of times, he or she may be more comfortable communicating with a prescriber. In contrast, if the pharmacy student who is communicating with the prescriber is a beginner, the student may be more nervous and less confident. The confidence and ability to intervene and communicate with a prescriber will improve with time and practice.

The experience of the prescriber must also be considered; for example, if a pharmacy student is working with a medical resident who is not familiar with the role of a pharmacist on a medical team, the student may have to explain the pharmacist’s role before requesting and going into the details of an intervention.

Additionally, the level of knowledge and understanding of the intervention being made can also be a factor. For example, if the pharmacist would like to change a patient to a different antihypertensive medication or increase the dose of a patient’s current antihypertensive medication, it would be helpful for the pharmacist to refer to the most recent Joint National Commission hypertension guidelines to support the recommendation being suggested. By having pertinent primary literature or guidelines to explain and support the rationale of a proposed intervention, it is more likely that the intervention will be accepted and implemented.

Approaching the Prescriber Face to Face to Make an Intervention

Making an intervention face to face is likely the most effective means of making an intervention, because you will have the prescriber’s attention and will be able to read any nonverbal expressions. At first, as a student or resident, this approach may seem the most intimidating. However, with time and practice your confidence and level of comfort will improve. Box 10.1 shows a sample dialog between a clinical pharmacist and a physician in which the pharmacist requests multiple interventions.

A common face-to-face interaction is during patient care rounds. In the course of patient care rounds at a teaching hospital, the medical residents and medical students often present each of their patients to the attending physician. Once the presentation is done and plans for care are being discussed, this is the time where the pharmacist or pharmacy student may be able to intervene. It is important to listen to the team’s plan carefully, though, because they may already have implemented the plan you are going to propose or they may provide new information that would affect your plan. In the latter situation, you may choose to wait until after patient care rounds to evaluate the new patient information and research your intervention further. When making an intervention during rounds, be sure not to interrupt a physician’s presentation of the patient; instead, one approach would be to wait until they are discussing plans for the disease state or problem that is pertinent to your intervention and, if your intervention was not already mentioned in the team’s plan, be ready to discuss it. For example, if you would like to increase the dose of lisinopril due to increased blood pressure, you might wait until they are discussing the plans for hypertension management. You could say, “I noticed that the blood pressure has consistently been above the patient’s goal. I recommend increasing the dose of lisinopril to 20 mg, rechecking the blood pressure in 1 week, and checking a serum creatinine and potassium in 5 to 7 days.” It is important to briefly state both the problem and a detailed solution. If the statement you make is too long or too detailed, you run the risk of losing the attention and understanding of the prescriber. Another approach might be to wait until the attending physician or resident physician asks if the pharmacist has any issues. However, it is not common for this to occur. Therefore, this might be something you address with your team on the first day of rounds each month or each time there is a turnover in the patient care team. For example, once you have introduced yourself as the pharmacist or pharmacy student for the team, you might say, “I am here to help manage and monitor the medications of the patients our team is caring for. Instead of potentially interrupting a thought you may have as you present your patient during rounds, it would be helpful if you ask if I have any pharmacy issues for each patient when you are discussing their care. If you forget, don’t worry, I will be sure to bring any issues I have forward at a time I feel is appropriate.”

BOX 10.1 Sample Dialog When Communicating with a Prescriber Face to Face to Make Multiple Interventions in a Hospitalized Patient

Pharmacist Carrie: “Hello, Dr. Smith. Do you have a minute before we start patient rounds to discuss some concerns I have about Ms. Morris?”

Dr. Smith: “Sure, Carrie, what are your concerns?”

Pharmacist Carrie: “First of all, I noticed her serum creatinine has been increasing over the last couple days. I am concerned about her being on metformin and the increased risk of lactic acidosis with the compromised renal function. I would like to discontinue the metformin, continue watching watch her glucose readings, and start insulin if she becomes hyperglycemic.”

Dr. Smith: “That sounds fine. I will write the order to discontinue metformin. What else?”

Pharmacist Carrie: “Her creatinine clearance is now 45. Her ciprofloxacin should be changed to 250 mg every 12 hours. Oh, and keep in mind, after tomorrow evening’s dose, she will have completed her therapy, so please write to discontinue it after tomorrow’s dose, as she seems to be much improved.”

Dr. Smith: “Great. I will change her ciprofloxacin to 250 mg every 12 hours and write to discontinue it after tomorrow night’s dose. Anything else?”

Pharmacist Carrie: “One last thing. I noticed she is being given pantoprazole PO for stress ulcer prophylaxis. It is not something she was taking at home, nor did I see any risk factors for stress ulcers. I would recommend discontinuing this.”

Dr. Smith: “Yes, definitely. Thanks for catching that.”

Pharmacist Carrie: “Great. Let me know if you have any questions as you write those changes.”

Dr. Smith: “Okay, thanks.”