2 Prescribing

Rational and effective prescribing

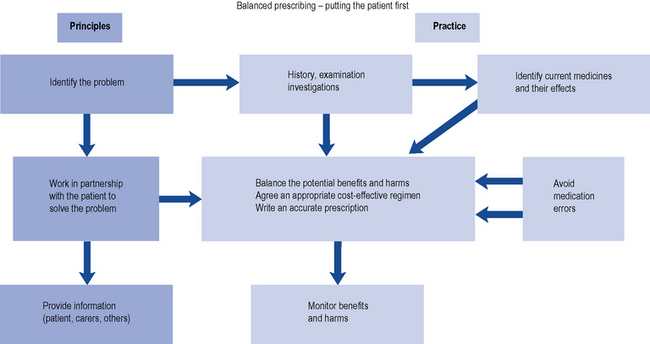

Prescribing a medicine is one of the most common interventions in health care used to treat patients. Medicines have the potential to save lives and improve the quality of life, but they also have the potential to cause harm, which can sometimes be catastrophic. Therefore, prescribing of medicines needs to be rational and effective in order to maximise benefit and minimise harm. This is best done using a systematic process that puts the patient at the heart of the process (Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1 A framework for good prescribing

(from Background Briefing. A blueprint for safer prescribing 2009 © Reproduced by permission of the British Pharmacological Society.)

What is meant by rational and effective prescribing?

There is no universally agreed definition of good prescribing. The WHO promotes the rational use of medicines, which requires that patients receive medications appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at the lowest cost to them and their community. However, a more widely used framework for good prescribing has been described (Barber, 1995) and identifies what the prescriber should be trying to achieve, both at the time of prescribing and in monitoring treatment thereafter. The prescriber should have the following four aims:

Another popular framework to support rational prescribing decisions is known as STEPS (Preskorn, 1994). The STEPS model includes five criteria to consider when deciding on the choice of treatment:

Pharmacists as prescribers and the legal framework

Evolution of non-medical prescribing

Independent prescribing is defined as ‘prescribing by a practitioner (doctor, dentist, nurse, pharmacist) who is responsible and accountable for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed or diagnosed conditions and for decisions about the clinic management required including prescribing’ (DH, 2006).

In 1986, a report was published in the UK (‘Cumberlage report’) which recommended that community nurses should be given authority to prescribe a limited number of medicines as part of their role in patient care (Department of Health and Social Security, 1986). Up to this point, prescribing in the UK had been the sole domain of doctors, dentists and veterinarians. This was followed in 1989 by a further report (the first Crown report) which recommended that community nurses should prescribe from a limited formulary (DH, 1989). The legislation to permit this was passed in 1992.

At the end of the 1990s, in line with the then UK government’s desire to widen access to medicines by giving patients quicker access to medicines, improving access to service and making better use of the skills of health care professionals, the role of prescriber was proposed for other health care professionals. This change in prescribing to include non-medical prescribers (pharmacists, nurses and optometrists) was developed following a further review (Crown, 1999). This report suggested the introduction of supplementary prescribers, that is, non-medical health professionals who could prescribe after a diagnosis had been made and a clinical management plan drawn up for the patient by a doctor (Crown, 1999).

Supplementary prescribing

The Health and Social Care Act 2001 allowed pharmacists and other health care professionals to prescribe. Following this legislation, in 2003, the Department of Health outlined the implementation guide allowing pharmacists and nurses to qualify as supplementary prescribers (DH, 2003). In 2005, supplementary prescribing was extended to physiotherapists, chiropodists/podiatrists, radiographers and optometrists (DH, 2005).

Supplementary prescribing is defined as a voluntary prescribing partnership between an independent prescriber (doctor or dentist) and a supplementary prescriber (nurse, pharmacist, chiropodists/podiatrists, physiotherapists, radiographers and optometrists) to implement an agreed patient-specific clinical management plan with the patient’s agreement. This prescribing arrangement also requires information to be shared and recorded in a common patient file. In this form of prescribing the independent prescriber, that is the doctor or if appropriate the dentist, undertakes the initial assessment of the patient, determines the diagnosis and the initial treatment plan. The elements of this patient-specific plan, which are the responsibility of the supplementary prescriber, are then documented in the patient-specific clinical management plan. The legal requirements for which are detailed in Box 2.1. Supplementary prescribers can prescribe Controlled Drugs and also both off-label and unlicensed medicines.

Non-medical independent prescribing

Following publication of a report on the implementation of nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing within the NHS in England (DH, 2006), pharmacists were enabled to become independent prescribers as defined under the Medicines and Human Use (Prescribing; Miscellaneous Amendments) Order of May 2006. Pharmacist independent prescribers were able to prescribe any licensed medicine for any medical condition within their competence except Controlled Drugs and unlicensed medicines. The restriction on Controlled Drugs included those in Schedule 5 (CD Inv.POM and CD Inv.P) such as co-codamol. At the same time, nurses could also become qualified as independent prescribers (formerly known as Extended Formulary Nurse Prescribers) and prescribe any licensed medicine for any medical condition within their competence, including some Controlled Drugs. Since 2008, optometrists can also qualify as independent prescribers to prescribe for eye conditions and the surrounding tissue. They cannot prescribe for parenteral administration and they are unable to prescribe Controlled Drugs.

Following a change in legislation in 2010, pharmacist and nurse, non-medical prescribers, were allowed to prescribe unlicensed medicines (DH, 2010).

Accountability

If a prescriber is an employee then the employer expects the prescriber to work within the terms of his/her contract, competency and within the rules/policies, standard operating procedure and guidelines, etc. laid down by the organisation. Therefore, working as a prescriber, under these conditions, ensures that the employer has vicarious liability. So should any patient be harmed through the action of the prescriber and he/she is found in a civil court to be negligent, then under these circumstances the employer is responsible for any compensation to the patient. Therefore, it is important to always work within these frameworks, as working outside these requirements makes the prescriber personally liable for such compensation. To reinforce this message it has been stated that the job descriptions of non-medical prescribers should incorporate a clear statement that prescribing forms part of the duties of their post (DH, 2006).

Ethical framework

Four main ethical principles of biomedical ethics have been set out for use by health care staff in patient–practitioner relationships (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001). These principles are respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, justice and veracity and need to be considered at all points in the prescribing process.

Autonomy

Gillick competence is used to determine if children have the capacity to make health care decisions for themselves. Children under 16 years of age can give consent as long as they can satisfy the prescriber that they have capacity to make this decision. However, with the child’s consent, it is a good practice to involve the parents in the decision-making process. In addition, children under 16 may have the capacity to make some decisions relating to their treatment, but not others. So it is important that an assessment of capacity is made related to each decision. There is some confusion regarding the naming of the test used to objectively assess legal capacity to consent to treatment in children under 16, with some organisations and individuals referring to Fraser guidance and others Gillick competence. Gillick competence is the principle used to assess the capacity of children under 16, while the Fraser guidance refers specifically to contraception (Wheeler, 2006).

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) protects the rights of adults who are unable to make decisions for themselves. The fundamental concepts within this act are the presumption that every adult has capability and should be supported to make their own individual decision. The five key principles are listed in Box 2.2. Therefore, any decision made on their behalf should be as unrestrictive as possible and must be in the patient’s own interest, not biased by any other individual or organisation’s benefit. Advice regarding patient consent is listed in Box 2.3.

Box 2.2 Overview of the five principles of the Mental Capacity Act

Beneficence

This is the principle of doing good and refers to the obligation to act for the benefit of others that is set out in codes of professional conduct, for example, pharmacists’ code of ethics and professional standards and guidance (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009). Beneficence is referred to both physical and psychological benefits of actions and also related to acts of both commission and omission. Standards set for professionals by their regulatory bodies such as the General Pharmaceutical Council can be higher than those required by law. Therefore, in cases of negligence the standard applied is often that set by the relevant statutory body for its members.

Professional frameworks for prescribing

The professional standards for pharmacists are defined within ‘Medicines, Ethics and Practice’ and contain additional requirements for pharmacists who are qualified as non-medical prescribers and also good practice guidance (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009). This guidance provides advice on a wide range of areas including self-audit, promotions, gifts from drug companies, written agreement with the employing organisation describing the prescriber’s scope of practice, liability and indemnity arrangements, competency to prescribe and not just prescribing and dispensing a medicine.

Off-label and unlicensed prescribing

The company which holds the marketing authorisation has the responsibility to compensate patients who are proven to have suffered unexpected harm caused by the medicine when prescribed and used in accordance with the marketing authorisation. Therefore, if a medicine is prescribed which is either unlicensed or off-label, the prescriber carries professional, clinical and legal responsibility and is therefore liable for any harm caused. Best practice on the use of unlicensed and off-label medicines is described in Box 2.4. In addition, all health care professionals have a responsibility to monitor the safety of medicines. Suspected adverse drug reactions should therefore be reported in accordance with the relevant reporting criteria.

Box 2.4 Advice for prescribing unlicensed and off-label medicines

(from Drug Safety Update, 2009; 2: 7, with kind permission from MHRA)

Consider

Communicate

Clinical governance

Clinical governance is described as having seven pillars:

Professional bodies have also incorporated clinical governance into their codes of practice. The four tenants of clinical governance are to ensure clear lines of responsibility and accountability; a comprehensive strategy for continuous quality improvement; policies and procedures for assessing and managing risks; procedures to identify and rectify poor performance in staff. Therefore, the professional bodies such as those of pharmacists, nurses and optometrists have also identified clinical governance frameworks for independent prescribing as part of their professional codes of conduct. The General Pharmaceutical Council, the UK pharmacy regulator, code of practice provided a framework not only for the individual pharmacist, non-medical prescriber, but also for their employing organisation. Suggested indicators for good practice are detailed in Box 2.5.