(1)

Department of Pathology, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, UK

Abstract

Premalignant endocervical glandular lesions are increasing in incidence. The various terminologies applied to these lesions (adenocarcinoma in situ or cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia), which are the precursors of usual type cervical adenocarcinoma, are discussed. These lesions are usually associated with high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The morphological features are discussed, as is the immunophenotype, differential diagnosis and management.

Keywords

Cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasiaAdenocarcinoma in situStratified mucin producing intraepithelial lesionIntroduction

Friedel and MacKay first described a premalignant endocervical glandular lesion which they termed adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) in 1953 [1]. Premalignant (and malignant) endocervical glandular lesions are much more uncommon than their squamous counterparts in the cervix but are increasing in incidence [2]. Part of this is a relative increase, compared to squamous carcinoma, because of a reduction in the latter in developed countries secondary to organised cervical screening programmes. However, there is also evidence that there is a real increase in the prevalence of premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions; while some of this may be due to better recognition of these lesions by pathologists, it is also probable that some of this increase is due to an increased prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and/or a change in the distribution of HPV types [2]. A study from Sweden found that the incidence of cervical adenocarcinoma increased from 1.59/100,000 person years in the 1950s and 1960s to 2.36 in the early 1990s [3]. The corresponding figures for cervical AIS were 0.04 and 1.37 reflecting an even greater increase [3]. Another study found the risk of cervical adenocarcinoma to be 14 times greater in women born in the early 1960s compared to those born before 1935 [4]. According to the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, the age-adjusted incidence rate of cervical adenocarcinoma per 100,000 women increased from 1.34 in the 1970s to 1.73 in the 1990s [4]. The ratio of patients with adenocarcinoma versus squamous carcinoma doubled in this period with the incidence of adenocarcinoma increasing to 26 % of all cervical carcinomas [4].

Terminology of Premalignant Endocervical Glandular Lesions

Cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia (CGIN) is the term in widespread use in the United Kingdom for endocervical glandular lesions which are the precursor of usual type cervical adenocarcinoma (referred to as mucinous adenocarcinoma of endocervical type by the World Health Organization (WHO)) [5, 6]. CGIN is divided into low grade and high grade. In WHO terminology, low grade CGIN corresponds to glandular dysplasia and high grade CGIN to AIS [5, 6] (Table 3.1). The CGIN terminology is recommended since, like the CIN classification scheme used for premalignant squamous lesions, this suggests there is a continuum of premalignant endocervical glandular lesions. However, the different terminologies in use make it difficult to directly compare various studies and the CGIN classification is not widely used outside the United Kingdom. Previously some authors divided premalignant endocervical glandular lesions into low grade CGIN, high grade CGIN and AIS or used a three tier grading system for CGIN [7–9]; however, high grade CGIN and AIS are now regarded as the same lesion and a two tier classification is recommended, although many authorities recognise only a single category of premalignant endocervical glandular lesion (high grade CGIN or AIS) (see below). The WHO definition of AIS is a lesion in which normally situated endocervical glands are partly or wholly replaced by cytologically malignant epithelium [6]. The WHO definition of glandular dysplasia is a glandular lesion characterised by significant nuclear abnormalities that are more striking than in glandular atypia but falling short of the criteria for AIS [6]. Most examples of CGIN (AIS) are of the so-called usual or endocervical type, although several morphological subtypes have been described (see below).

Table 3.1

Comparison of WHO and United Kingdom Systems for Classification of Premalignant Endocervical Glandular Lesions

WHO | United Kingdom |

|---|---|

Glandular dysplasia | Low grade CGIN |

Adenocarcinoma in-situ | High grade CGIN |

Aetiology and Pathogenesis of Premalignant Endocervical Glandular Lesions

Most, but not all, premalignant (and malignant) endocervical glandular lesions are associated with high risk HPV, most commonly types 16 and 18 [10–12]; HPV 18 is proportionally much more common than in CIN and is probably more prevalent than HPV 16 in premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions [10–12]. In a significant percentage and probably a majority of cases, premalignant endocervical glandular lesions coexist with CIN since both are, for the most part, HPV-related lesions; in some, but not all, cases the same HPV type is found in the premalignant squamous and glandular lesion, although this is not always the case [13]. Many cases of CGIN are identified as an incidental finding in a patient with CIN and, in general, CGIN occurs in a similar age group to CIN. There is a suggestion that premalignant and malignant endocervical glandular lesions may be associated with the use of hormonal agents but this is not proven [14, 15].

More uncommon morphological variants of cervical adenocarcinoma, including clear cell, mesonephric, gastric type and adenoma malignum, are usually not HPV-related and do not arise from CGIN [10, 11]. It has been suggested that the benign endocervical glandular lesion, lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (see Chap. on 2) may be a precursor of adenoma malignum and gastric type cervical adenocarcinoma [16–18].

Clinical Features of Premalignant Endocervical Glandular Lesions

Most women with a premalignant endocervical glandular lesion are asymptomatic and the lesion is discovered following an abnormal cervical smear. The smear result may have suggested a glandular or squamous abnormality or the premalignant glandular lesion may be an incidental finding in a patient with a premalignant or malignant squamous lesion. The age range is similar to that of patients with CIN, both the median and mean age being in the fourth decade (10–15 years younger than the corresponding median and mean ages of patients with cervical adenocarcinoma).

Premalignant endocervical glandular lesions are more likely to be seen in an excisional rather than a punch biopsy since they are often not visible colposcopically and excision biopsy of the transformation zone is usually undertaken if a premalignant glandular lesion is strongly suspected on a cervical smear.

Evidence for Low Grade CGIN Being a Premalignant Lesion

It seems logical to assume that there is a precursor lesion to high grade CGIN. However, low grade CGIN is much more uncommon than high grade and it is unusual to identify low grade CGIN in pure form without a high grade lesion. Some authorities doubt the existence of low grade CGIN (glandular dysplasia) and do not diagnose this since the morphological features are not clearly defined, the diagnosis is poorly reproducible, the natural history is not known and there are no clear management guidelines. Points of evidence in favour of low grade CGIN being a precursor of high grade include the observation that in some studies low grade CGIN has occurred in a younger age group than high grade, the fact that low grade CGIN may be seen adjacent to high grade and the presence of similar HPV types in some studies [19–23]. On the other hand, it is unclear what criteria were used to diagnose low grade CGIN in these studies, low grade CGIN is uncommonly seen in pure form and in many cases there is an abrupt transition between normal glandular epithelium and a high grade glandular lesion.

A reasonable approach is to accept that low grade CGIN is a precursor of high grade but it is uncommonly seen in the absence of a high grade lesion and it should not be diagnosed unless the morphological features are unequivocally those of a premalignant lesion, although of lesser severity than high grade CGIN; diffuse p16 immunoreactivity would be a prerequisite to the diagnosis. If diagnosing low grade CGIN in pure form, it is recommended to state on the pathology report that management should be as for high grade CGIN. An alternative, and equally acceptable, viewpoint is that low grade CGIN (glandular dysplasia) is not diagnosed but rather that cases which are equivocal for high grade CGIN be subject to immunohistochemical analysis. If p16 is negative or focally positive and there is a low MIB1 proliferation index, the lesion should be regarded as benign but if p16 is diffusely positive and there is an elevated MIB1 proliferation index, it is classified as high grade CGIN [24].

Morphological Features of CGIN

Most examples of CGIN are of so-called usual or endocervical type but several subtypes have been described, including intestinal, endometrioid and tubal (discussed below). Clear cell and serous variants have also been postulated to exist but these are likely to merely represent growth patterns at the periphery of primary clear cell and serous carcinomas of the cervix rather than true precursor lesions.

Usual or Endocervical Type CGIN

This is the most common type of CGIN, although the term usual or endocervical type is not generally used in the pathology report. CGIN usually occurs at or close to the transformation zone and there is coexistent CIN in a high proportion of cases. It was previously considered that both skip lesions and extension high up the endocervical canal were common in CGIN but, although these sometimes occur, both are relatively uncommon [25, 26]; tangentional sectioning may result in an impression of skip lesions. However, there have been occasional reports of CGIN with extension to the endometrium [27, 28]. Some of these cases have been misdiagnosed as a primary adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus or have resulted in ovarian metastasis, sometimes even in the absence of obvious invasion within the cervix [27]. Those cases with ovarian metastases have not generally been associated with an adverse outcome and the ovarian disease is likely secondary to transuterine and transtubal spread [27].

CGIN is first identified on low power examination, which is the initial clue to diagnosis, given the contrast to the normal endocervical glands; it is not necessary to examine every endocervical gland under high power to look for CGIN. In high grade CGIN, the abnormal glands are confined to the pre-existing “normal” endocervical glandular field which, in itself, may be quite complicated. In some cases, there is accentuation of the normal lobular endocervical glandular architecture (Fig. 3.1). There is often an abrupt transition between normal and abnormal epithelium both within and between glands (Fig. 3.2). Usually both the surface and crypt epithelium is involved with mucin depletion, nuclear stratification (often with the long axis of the cells perpendicular to the base), atypia, hyperchromasia with coarse clumped chromatin and loss of polarity. There are usually easily identifiable mitotic figures, especially on the luminal aspect of the glands, sometimes with atypical mitoses; however, in some cases mitoses are relatively sparse. Apoptotic bodies are a characteristic and relatively constant feature and are usually seen in the non-luminal aspect of the glands (Fig. 3.3) [29–31]; sometimes they are numerous. In general, apoptotic bodies are more commonly seen and are more numerous in high grade CGIN than in invasive cervical adenocarcinomas. The combination of luminal mitoses and basal apoptotic bodies is a characteristic feature of high grade CGIN. Focal intraglandular papillae and a cribriform architecture may be seen in high grade CGIN (Fig. 3.4) but when these features are prominent and widespread, this should result in consideration of invasive adenocarcinoma; in those cases of CGIN with a cribriform architecture, the glandular outlines should be round and not irregular. There may be inflammation of the stroma surrounding the glands in CGIN but there is no desmoplastic reaction. Since CGIN is confined to the pre-existing endocervical glandular field, it may also involve dilated crypts. Occasionally, CGIN involves a pre-existing benign endocervical glandular lesion such as papillary endocervicits, microglandular hyperplasia or tunnel clusters and this may result in diagnostic problems and consideration of adenocarcinoma for obvious reasons. The immunophenotype of high grade CGIN is discussed below (section on “Immunohistochemistry of premalignant endocervical glandular lesions”).

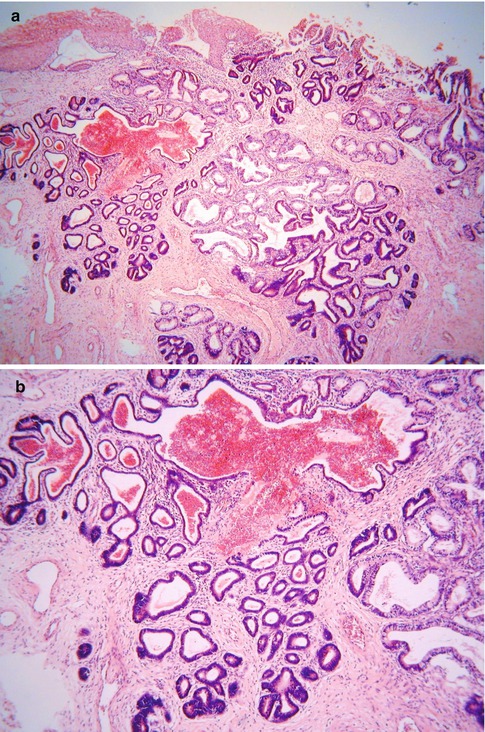

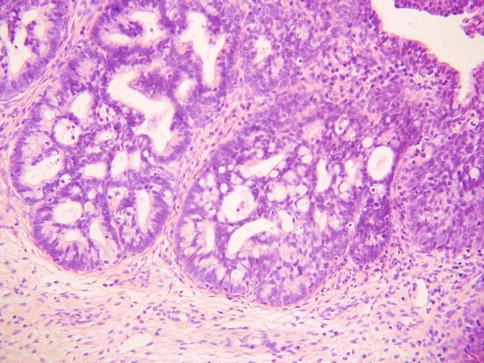

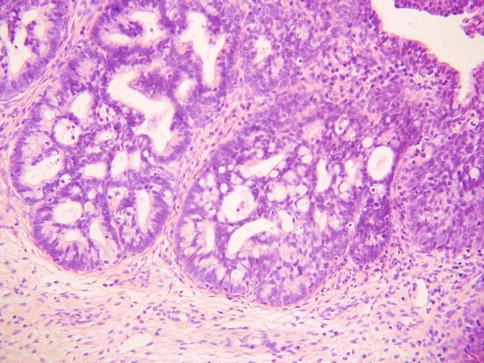

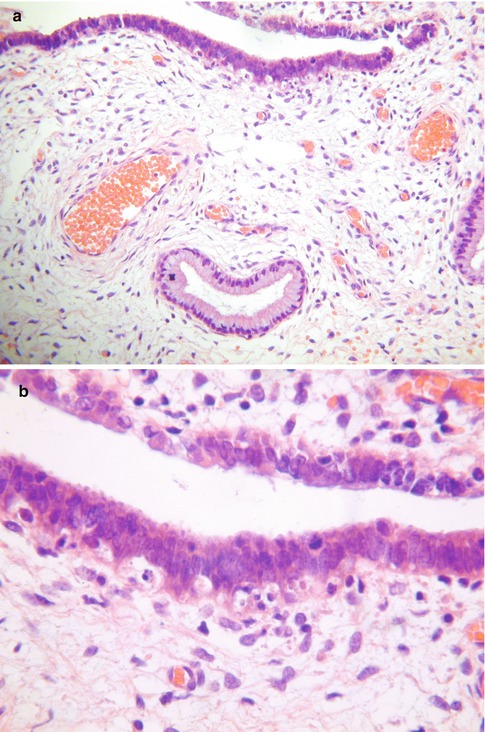

Fig. 3.1

Low power view of high grade CGIN showing accentuation of the normal lobular endocervical glandular architecture (a). Higher power of same lesion (b)

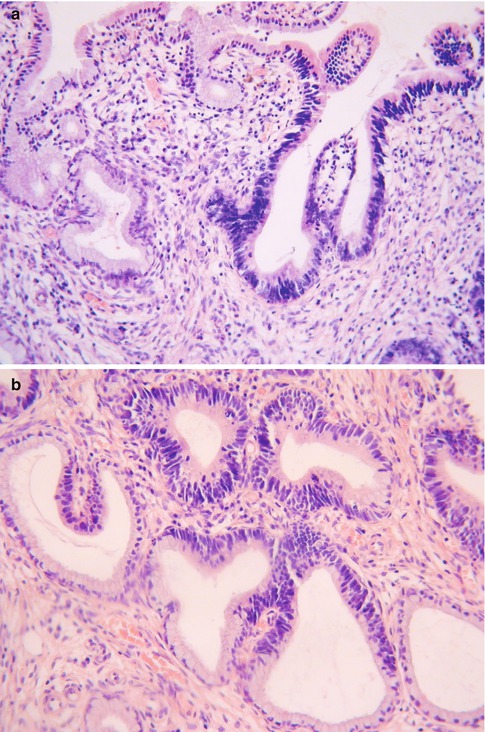

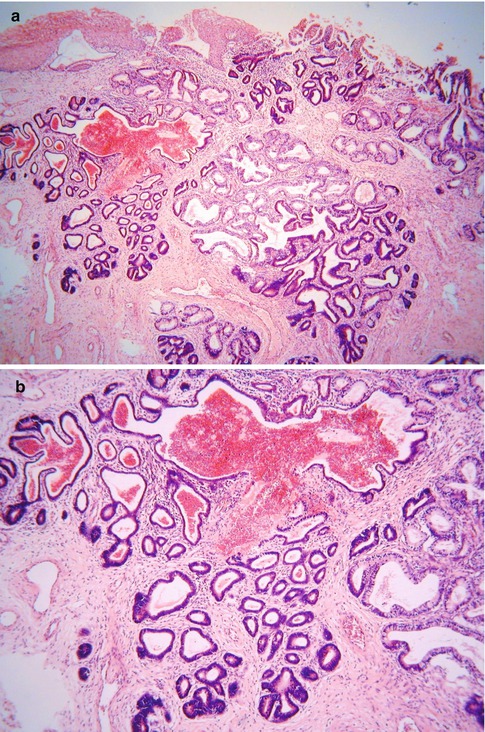

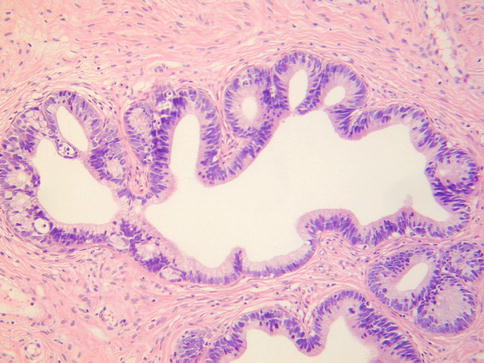

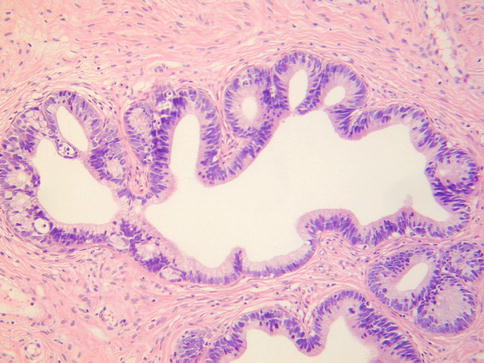

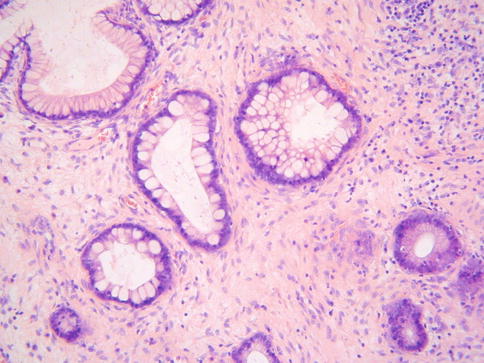

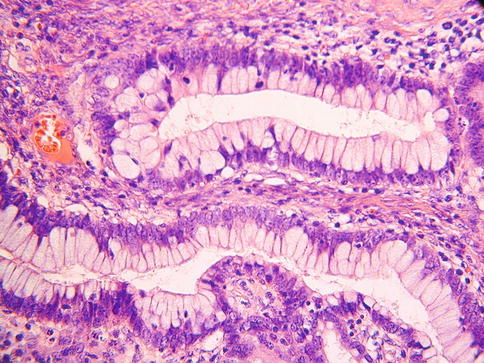

Fig. 3.2

Abrupt transition between normal endocervical glands and glands involved by high grade CGIN (a). Even within individual glands there may be a sharp demarcation between normal and high grade CGIN (b)

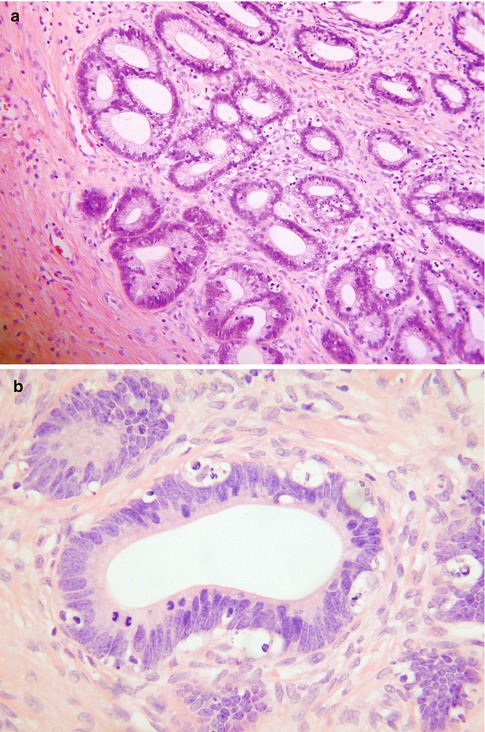

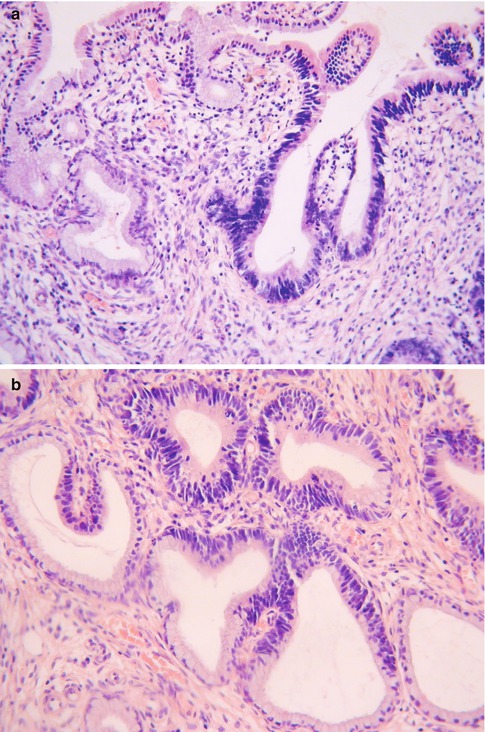

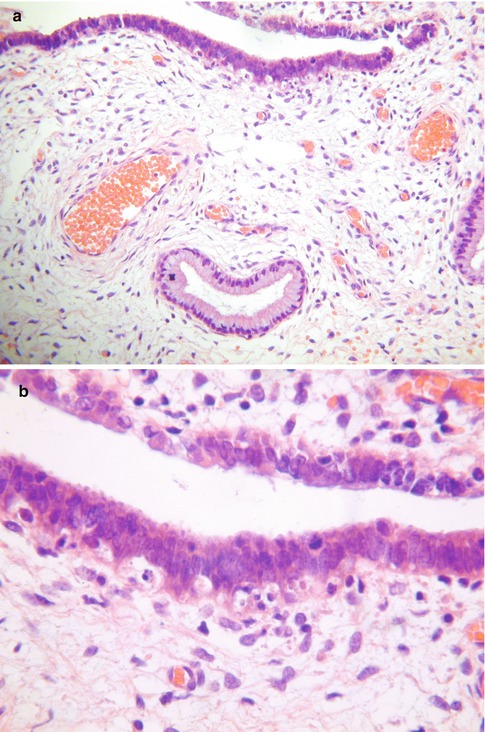

Fig. 3.3

Intermediate power (a) and high power (b) of high grade CGIN exhibiting nuclear hyperchromasia and atypia with luminal mitoses and basal apoptotic bodies

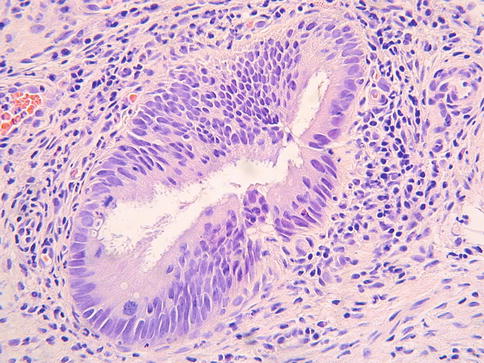

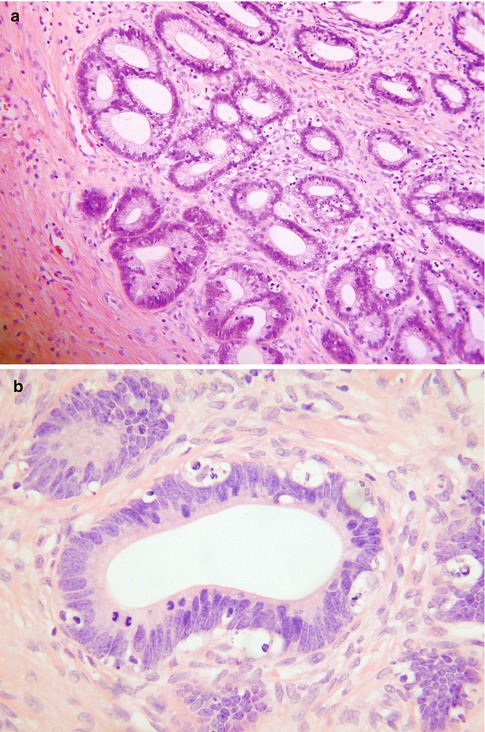

Fig. 3.4

High grade CGIN exhibiting focal cribriform architecture

As discussed, low grade CGIN is a much more uncommon and subtle lesion. The morphological features are similar to those of high grade CGIN but the cytological abnormalities are less marked. There is usually nuclear hyperchromasia but there is only mild atypia, mucin depletion, nuclear stratification and loss of polarity (Fig. 3.5). Mitotic figures are usually present but not numerous. The presence of apoptotic bodies may be a useful diagnostic clue.

Fig. 3.5

Low grade CGIN with only mild nuclear atypia and occasional luminal mitoses and basal apoptotic bodies

Superficial CGIN (superficial AIS) has been used as a term for CGIN which is confined to the surface mucosa and crypt openings (Fig. 3.6) [32]. It has been speculated that this represents an early form of CGIN occurring in a younger age group than more established CGIN. In contrast to the latter, in superficial CGIN there is usually only mild nuclear atypia with rare to absent apoptotic bodies. Given its superficial nature, the lesion may not be obvious at low power and may be overlooked, especially since the cytological abnormalities can be subtle; immunohistochemical staining for p16 and MIB1 may assist in diagnosis (see below).

Fig. 3.6

Superficial high grade CGIN where abnormal glands are confined to the surface and superficial crypt openings (a). On high power, mitoses and apoptotic bodies are seen (b)

A scoring system for non-invasive endocervical glandular lesions to be used primarily in research practice has been proposed [33]. Using this system, a final numerical score is based on the summation of three individual scores given for nuclear atypia, stratification and the sum of mitoses and apoptoses [33]. While this scoring system may be useful in a research setting, it is of limited value in routine pathological practice.

Intestinal Type CGIN

After the usual type, the most common variant of CGIN is the intestinal type where goblet cells are present (Fig. 3.7). Paneth cells and/or neuroendocrine cells also occur more uncommonly [26, 34]. Intestinal type CGIN is usually associated with usual type; in one study, intestinal differentiation was present in 29 % of cases of CGIN, always in association with usual type [26]. When intestinal type epithelium with goblet cells is present in the cervix, this almost always indicates a premalignant or malignant endocervical glandular lesion, although the nuclear features of malignancy may be subtle because of compression by intracytoplasmic mucin globules (Fig. 3.8). “Benign” intestinal metaplasia (unassociated with CGIN) rarely exists in the cervix, although it is occasionally seen in association with lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia and other forms of gastric metaplasia (see Chap. 2, section on “Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia”) [35, 36]. One study found that intestinal type CGIN is more likely than the usual type to be associated with early invasion [34].

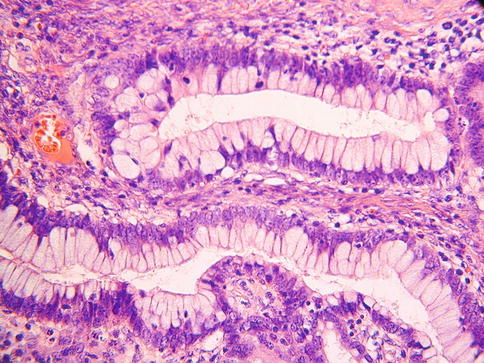

Fig. 3.7

Intestinal type CGIN characterised by the presence of goblet cells

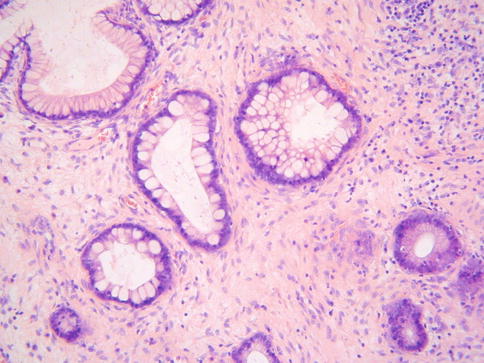

Fig. 3.8

Intestinal type CGIN where the nuclei are compressed by goblet cells

Most cases of intestinal type CGIN are HPV-associated [37]. However, it has been suggested that a minority of examples of intestinal type CGIN are not HPV-associated [37]. In one study, cases of intestinal type CGIN which were not HPV-associated occurred in an older age group than HPV-associated CGIN, were less likely to express p16 diffusely and exhibited a lower MIB1 proliferation index [37].

Endometrioid Type CGIN

An endometrioid variant of CGIN (AIS) has been described. However, this is likely to merely represent usual type CGIN with marked depletion of intracytoplasmic mucin resulting in a pseudoendometrioid appearance. As such, it is doubtful whether a true endometrioid variant of CGIN exists or whether it could be distinguished from usual type.

Tubal (Ciliated) Type CGIN

Occasional examples of CGIN contain cilia and are referred to as being of tubal or ciliated type (Fig. 3.9) [38]. This uncommon variant of CGIN usually occurs in association with usual type. The main differential diagnosis is tuboendometrial metaplasia with a degree of nuclear atypia. Apoptotic bodies are a useful diagnostic clue in favour of CGIN but these should not be mistaken for the intraepithelial lymphocytes surrounded by a halo which are commonly seen in tuboendometrial metaplasia. It has been suggested that tubal type CGIN may arise from tuboendometrial metaplasia or atypical tuboendometrial metaplasia but there is no firm evidence for this. p16 may be useful in the distinction from tuboendometrial metaplasia in that CGIN is diffusely positive while tuboendometrial metaplasia is usually negative or exhibits patchy immunoreactivity. However, the immunophenotype of tubal type CGIN has not been studied given the rarity of the lesion. Given its rarity, caution should be exercised before making a diagnosis of tubal type CGIN. The nuclear features should unequivocally be those of a malignant lesion since tuboendometrial metaplasia may exhibit a significant degree of nuclear atypia.