CHAPTER 14 Pre- and postnatal development

PRENATAL STAGES

To overcome these difficulties, early embryos have been graded or classified into developmental stages or ‘horizons’, on the basis of both internal and external features. The study of the Carnegie collection of embryos by Streeter (1942, 1945, 1948), and the continuation of this work by O’Rahilly & Müller (1987), provided, and continues to provide, a sound foundation for embryonic study and a means of comparing stages of human development with those of the animals routinely used for experimental study, namely the chick, mouse and rat. Recent use of ultrasound for the examination of human embryos and fetuses in utero has confirmed much of the staging data.

The development of a human from fertilization to birth is divided into two periods, embryonic and fetal. The embryonic period has been defined by Streeter as 8 weeks postfertilization, or 56 days. This timescale is divided into 23 Carnegie stages, a term introduced by O’Rahilly & Müller (1987) to replace developmental ‘horizons’. The designation of stage is based on external and internal morphological criteria and not on length or age.

Embryonic stages

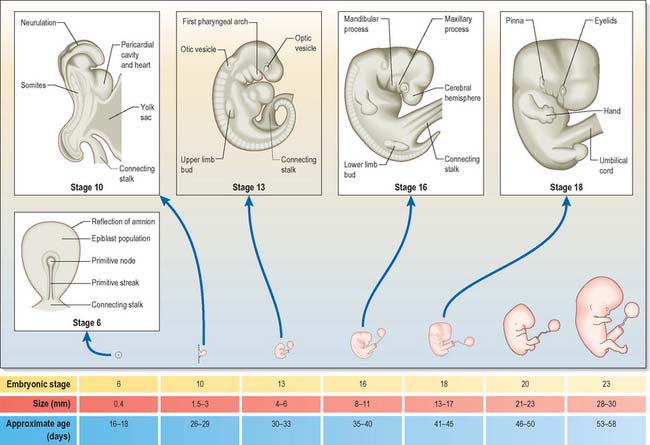

Embryonic stages 1–10 are shown in detail in Fig. 8.1. It should be noted that estimations of embryonic length may be 1–5 mm less than equivalent in vivo estimates, reflecting the shrinkage caused by the fixation procedures that are inevitably used in embryological studies. O’Rahilly & Müller (2000) have revised some of the ages that were previously assigned to early embryonic stages, pointing out that inter-embryonic variation may be greater than had been thought and that consequently some ages may have been underestimated. They note that as a guide, the age of an embryo can reasonably be estimated from the embryonic length within the range 3–30 mm, by adding 27 to the length. Correlating the age of any stage of development to an approximate day may be unreliable, and a generalization using the number of weeks of development might be now more appropriate.

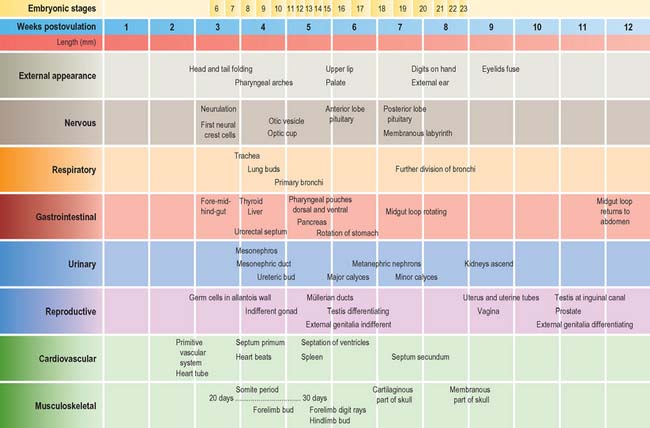

The stages of development encompass all aspects of internal and external morphogenetic change that occur within the embryo within the duration of the stage. They are used to convey a snapshot of the status of the development of all body systems within a particular timeframe. Figure 14.1 shows the external appearance of embryos from stage 6 to stage 23, with details of their size and age in days. The correlation of external appearance of the embryo with internal development is shown in Fig. 14.2.

Fetal staging

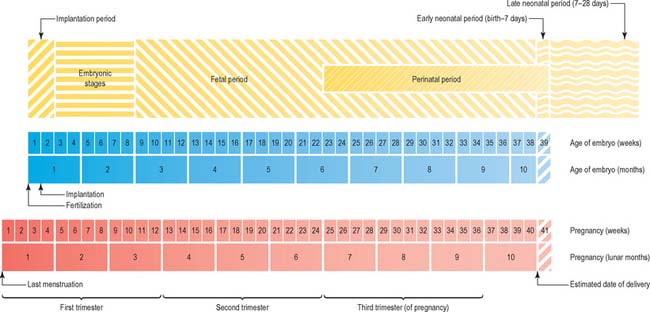

Currently there is no satisfactory system of morphological staging of the fetal period of development, and the terminology used to describe this time period reflects this confusion. The terms ‘gestation’, ‘gestational age’ and ‘gestational weeks’ are considered ambiguous by O’Rahilly & Müller (2000) who recommend that they should be avoided. However, they are widely used colloquially within obstetric practice. Staging of fetal development and growth is based on an estimate of the duration of a pregnancy. Whereas development of a human from fertilization to full term averages 266 days, or 9.5 lunar months (28 day units), the start of pregnancy is traditionally determined clinically by counting days from the last menstrual period; estimated in this manner, pregnancy averages 280 days, or 10 lunar months (40 weeks). Figure 14.3 shows the embryonic timescale used in all descriptions of embryonic development and the obstetric timescale used to gauge the stage of pregnancy. Studies that discuss fetal development and the gestational age of neonates, particularly those born before 40 weeks’ gestation, use the clinically estimated stages and age unless they specifically correct for this. If a fetal ageing system is used, it must be remembered that the age of the fetus may be 2 weeks more than a comparable fetus that has been aged from postovulatory days.

Fig. 14.3 The two timescales used to depict human development. Embryonic development, in the upper scale, is counted from fertilization (or from ovulation, i.e. in postovulatory days; see O’Rahilly & Müller 1987). Throughout this book, times given for development are based on this scale. The clinical estimation of pregnancy is counted from the last menstrual period and is shown on the lower scale; throughout this book, fetal ages relating to neonatal anatomy and growth will have been derived from the lower scale. Note that there is a 2-week discrepancy between these scales. The perinatal period is very long, because it includes all preterm deliveries.

The predicted date of full term and delivery is revised after routine ultrasound examination of the fetus. Early ultrasound estimation of gestation increases the rate of reported preterm delivery (delivery at <37 weeks) compared with estimation based on the date of the last menstrual period (Yang et al 2002), possibly because delayed ovulation is more frequent than early ovulation: the predicted age of a fetus estimated from the date of the last menstrual period may differ by more than 2 weeks from estimates of postfertilization days.

A number of biometric indices used to determine fetal growth in utero have been evaluated ultrasonographically; the consensus appears to be that some revision of fetal gestational age may be required when using charts based on fetal biometry, and that using fewer biometric variables for the estimation produces a larger standard error. First-trimester growth charts based on biparietal diameter, head circumference and abdominal circumference of normal singleton fetuses correlated against crown–rump length (from 45 to 84 mm) are said to be more accurate than gestational age (Salomon et al 2003). O’Rahilly & Müller (2000) recommend that the term ‘crown–rump length’ should be replaced by greatest length, exclusive of lower limbs in ultrasound examination. Femur length/head circumference ratio may be a more robust ratio to characterize fetal proportions than femur length/biparietal diameter (Johnsen et al 2005), and combining kidney length, biparietal diameter, head circumference and femur length also increases the precision of dating (Konje et al 2002). Johnsen et al (2004) reported that analysis of measurements of biparietal diameter and head circumference at 10–24 weeks gestation gave a gestational age assessment of 3–8 days greater than charts in present use.