http://evolve.elsevier.com/Edmunds/NP/

Many sources describe the importance of prescriptive authority for full implementation of the health provider’s role; however, very few texts describe the mechanics and technicalities of the actual process. Students of all disciplines with prescriptive authority admit to some anxiety in writing their first prescriptions. They are concerned about not only what they write, but how they write it. However, most clinicians describe learning this process on the job, under the tutelage of another clinician or preceptor, often while under pressure to master other skills. Casual observation of prescriptions submitted to a pharmacy reveals the wide array of formats used in writing prescriptions, some leading to a greater chance for errors than others. Research also shows that, similar to writing a check, the format with which one begins is often the format that persists over time, even if it is not the best.

Who May Write Prescriptions?

State law identifies those health care providers who are authorized to write prescriptions. This fact is because of the state-by-state variation in prescriptive authority. Traditionally, physicians have had full prescriptive authority, dentists and podiatrists have had prescriptive authority for a limited formulary, and veterinarians have had the ability to prescribe, dispense, and administer a variety of medications. State laws have been amended in every state to provide prescriptive authority to certain other providers, such as doctors of osteopathy, physician assistants (PAs), advanced practice nurses (APNs), or specifically nurse practitioners (NPs), certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), and in some states clinical nurse specialists (CNSs). Prescriptive authority may be granted directly to these providers or indirectly through delegated authority from a physician (see Chapter 2 for information on APNs and PAs). Each state determines the qualifications and credentials that are essential for a provider to obtain prescriptive authority; these may include specific courses in pharmacology before prescriptive authority is granted, as well as ongoing requirements for continuing education in pharmacology.

The exact extent of prescriptive authority is also determined by the state through legislative statute. This includes the types of drugs that the provider is authorized to prescribe. Over-the-counter medications require no state authorization. Indeed, these medications often are initiated and controlled by patients. Drugs that require a prescription include legend drugs and controlled substances. Legend drugs include the vast majority of medications, such as those given for hypertension, diabetes, or asthma. If a state determines that providers may write prescriptions for controlled substances, it also establishes a mechanism for monitoring that activity, such as granting the provider a number or putting the provider on an approved list. Once he has received documentation of this authority from the state, the health care provider is eligible to apply to the federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for a federal DEA number to be used on all prescriptions for controlled substances.

The DEA oversees controlled substances. This agency attempts to limit professionals who may prescribe controlled substances to those who are authorized and competent to do so and to monitor the activity of such individuals to make certain they are in conformance with federal law. Such monitoring is essential because of the potential for misuse and abuse of these substances by both patients and providers. The DEA does not define who is to receive DEA numbers but relies on the states for this information (U.S. Department of Justice, DEA, 2006). States issue a state-controlled substance license. This number seems to have little purpose other than to document for the DEA that the applicant is recognized as a prescriber within the state and is eligible for the federal DEA number. The DEA website lists the controlled substance authority for midlevel practitioners by discipline in the state in which they practice (http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/practioners/index.html).

The health care provider who seeks a federal DEA number may obtain an application by calling 202-307-7255; by going to the DEA website at www.DEADiversion.usdoj.gov; or by writing to the Drug Enforcement Administration Registration Division, Washington, DC 20537, and submitting the appropriate information and fees. Fees are sufficiently high to deter casual acquisition. Currently the rate for pharmacies, hospitals/clinics, practitioners, teaching institutions, or midlevel practitioners is $731, which covers 3 years. Providers must indicate on the application the specific schedules of drugs that they are authorized by the state to prescribe. Physician numbers begin with A if they have had the DEA number for some time or with F if they are a new registration. Nonphysician prescribers are required to fill out a specific addendum to the DEA application to validate state authority to engage in the prescription of controlled substances. DEA numbers issued to “midlevel providers” begin with the letter M, followed by a number that corresponds to the first letter of the last name (i.e., E for Edwards) and a computer-generated sequence of numbers. Physician and midlevel practitioners’ manuals, available by special request, contain essential rules and regulations related to use or misuse of the DEA number. If applicants meet the DEA requirements, they are issued a number. One exception is that military and U.S. Public Health Service physicians are exempt from registration. This number is valid for 3 years and then may be renewed. This federal number is also reported to the state and is included in the materials distributed to pharmacists in that state (U.S. Department of Justice, DEA, 2006).

Drug Schedules

Federal statute has established five schedules of controlled substances, ranked in order of their abuse potential and in inverse proportion to their medical value. These schedules and a definition of each are listed on the DEA website. A complete list of controlled substances may be obtained by writing to Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402, or by consulting the website for this office. The drugs in these schedules are revised periodically by the DEA as circumstances warrant.

Drugs in Schedule I have the highest potential for abuse, and their use is limited to research protocols, instructional purposes, or chemical analysis. Ongoing research may eventually establish a medical role for some of these substances under selected circumstances. On the other end of the spectrum, Schedule V drugs are available by prescription or may be sold over the counter in some states, depending on state law (U.S. Department of Justice, DEA, 2012). See Table 10-1 for a sample Schedule of Controlled Drugs.

TABLE 10-1

Federal Schedule of Controlled Drugs

From U.S. Department of Justice, DEA: Prescribers’ manual, Washington, DC, 2008, U.S. Department of Justice.

Controlled drugs often have restrictions on the number of refills permitted. When they are dispensed to a patient via prescription, the label of any controlled substances under Schedule II, III, or IV must contain a symbol that designates the schedule to which it belongs and the following warning: “Caution: Federal law prohibits the transfer of this drug to any person other than the patient for whom it was prescribed.” Internet and mail-order pharmacies may not fill prescriptions for controlled substances.

Classification of drugs into these schedules is flexible. Thus, any drug can be placed under control, upgraded or downgraded, or possibly even removed from control over time. For example, new information might cause a change in schedule classification, or epidemic abuse of an uncontrolled drug may cause it to be added to the controlled substance list.

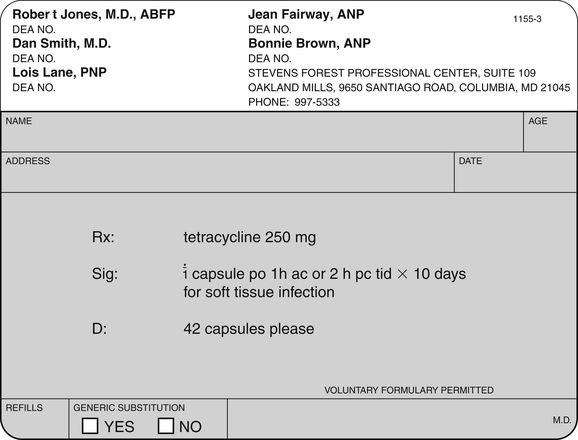

Components of the Traditional Prescription

Although state law may mandate the specifics of what is required on a prescription, there is general agreement about some things that should be included, whether required by law or not and whether a preprinted prescription pad is used or the prescription is transmitted electronically. Most states insist that the hospital name or the imprinted name of the prescriber, along with credentials, address, and telephone number, must be preprinted on the prescription pad for controlled substances but not for noncontrolled drugs. It is important, however, for the pharmacist to be able to easily contact the prescriber. In institutions where there are many prescribers, an institutional prescription pad may allow the prescriber to use a number rather than having all prescriber names printed on the pad. Prescriptions must be preprinted, typed, or written in ink and must be signed by an authorized prescriber to be valid. For a good example of a prescription, see Figure 10-1.

Is there one correct way to write a prescription? Yes. And it should be followed consistently and without deviation each time a prescription is written. It contains the components as identified in the sections on top portion, middle portion, and bottom portion that follow.

Top Portion

The top portion of the preprinted prescription form contains the patient’s name, address, and age or birth date. The patient’s weight also may be included here when relevant. The date on which the prescription is written is required.

Middle Portion

The middle portion of the prescription, the part that is individualized for each patient, contains five main items:

First, it is important for the patient to understand how to take the medication. The prescription should be specific about this and should not just indicate “Take as directed.” Research has shown that failure to write instructions clearly is responsible for many of the medication errors that patients make. Patients often do not understand instructions, become confused over time, or fail to make changes when therapy is modified (Aspinall et al, 2007). The imprecision of poorly written directions can also influence a patient’s ability to comply. To improve patient recall and reduce administration errors, patients require explicit directions. A high percentage of reported administrative errors result from the direct failure of patients to comprehend the directions on the prescription label (Cohen, 2007). In one study, when given a prescription for tetracycline 250 mg with the directions “Take 1 capsule every 6 hours,” only 36% of 67 participants interpreted the directions to mean around the clock, for a total of 4 doses in 24 hours. Approximately 25% would have been noncompliant by omitting the late-night dose because they would have divided the day into three 6-hour periods while they were awake. Although in this instance, the pharmacist has adequate information to counsel the patient, the example demonstrates the importance of prescription writing and labeling (Aspinall et al, 2007). Caregivers express greater satisfaction with the prescribing experience when they are given the rationale for and more informative dosing information, especially when caring for pediatric patients (Barrett et al, 2011).

Second, clarity and precision in writing instructions also help the pharmacist. Federal regulations now mandate that pharmacists must provide education and counseling to patients regarding their medication. Having specific information about why the patient is taking the medication and how the patient should take the medication allows the pharmacist to help reinforce the provider’s directions, discover errors in the writing or the filling of the prescription, and obtain feedback about how patients think they should take the medication. Given the growing number of new drugs on the market, identifying the symptom, indication, or intended effect for which the medication is being prescribed becomes more important and can be added in just a few words—for example, “for nausea,” “at headache onset,” and so on. This additional information allows the pharmacist who is dispensing the prescription to help assess compliance and reinforce the provider’s instructions. An example of this can be seen with propranolol, which may be used to treat several different problems. It would be nonsensical for a pharmacist to explain how important it is for a patient to take the medication to control high blood pressure when the patient is being treated for migraine headaches. Knowing the intent of the treatment will aid the pharmacist in communicating with the patient and providing feedback to the provider (Bernstein et al, 2007).

Finally, specific instructions on the container assist the prescriber in reviewing medications ordered by other prescribers. Patients should always bring all medications they are taking to each office visit. Errors may be detected more easily when instructions on each container are examined. The number of tablets/capsules/teaspoons is designated by small roman numerals—for example, one = i, two = ii, three = iii, and so on. Examples of instructions might include “Take i tablet 1 hour before eating or 2 hours after eating 3 times a day”; “Mix i teaspoon in a full glass of orange juice to be taken morning and evening”; or “Take ii capsules with food each morning.” See Table 10-2 for examples of abbreviations commonly used in prescribing medications.

TABLE 10-2

Abbreviations Commonly Used in Prescription Writing

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| sig | Directions for use |

| qAM | Every morning |

| bid | Two times daily while awake |

| tid | Three times daily while awake |

| qid | Four times daily while awake |

| q8h | Every 8 hours around the clock |

| ac | Before meals |

| pc | After meals |

| hs | At hour of sleep or bedtime |

| tsp | Teaspoon |

| prn | As needed |

Bottom Portion

The bottom portion of the preprinted prescription form contains other standard information. The number of refills and the prescriber’s signature and credentials are required. If a controlled substance is prescribed, the federal DEA number is also to be listed. Finally, some prescriptions include a box that should be checked if a generic substitution is authorized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree