8 Practical procedures and patient investigation

General precautions

• Needles should not be resheathed and all disposable sharp instruments discarded by the operator should be placed in an appropriate container to minimize the risk of needle-stick injury

• Drapes and other soiled equipment should be placed in appropriate containers

• Gloves and gown should only be removed after all used instruments and disposable equipment have been placed in appropriate containers.

Aseptic technique

Transmission of infection is an ever-present problem, and the risk of spread should be minimized. As a minimum precaution, the skin should be cleansed with an antiseptic solution before all procedures, and sterile instruments used. For some procedures, such as central venous catheterization, bladder catheterization, insertion of chest drains and lumbar puncture, a full aseptic technique must be employed. The steps required are outlined in Table 8.1.

Suturing

Suture materials

Non-absorbable sutures

Non-absorbable sutures may be classified into three groups:

1. Natural braided sutures (e.g. silk, linen) have good handling qualities and knot easily and securely. Their disadvantage is increased tissue reaction and suture line sepsis, caused by the capillary action of the braided material drawing micro-organisms into the suture track. Such materials also lose tensile strength quickly with time, or when wet.

2. Synthetic braided materials (e.g. Nurolon, Ethibond, Mersilene) cause less tissue reaction than natural materials. They have good handling qualities and knot easily and securely.

3. Synthetic monofilament materials (e.g. nylon, polypropylene) have less drag through the tissues and cause little tissue reaction. They are free from the capillary effect of braided sutures and cause less suture track sepsis. However, they handle less well because of increased ‘memory’ (i.e. they retain the configuration in which they were packaged). Knots in monofilament sutures are less secure than those in braided or natural sutures, requiring multiple throws on each one.

Suturing the skin

• Tissue should be handled gently. The wound should not be rubbed with swabs. Blood in a wound is removed by pressing a swab on to it

• Haemostasis should be meticulous to prevent wound haematoma

• All foreign material and devitalized tissues should be removed. Where this is prevented by heavy contamination, delayed primary suture or secondary suture should be considered

• Potential spaces (dead space) in the wound should be closed using absorbable suture material such as Vicryl. Where this is not possible, a suction drain is led from the potential space before more superficial layers are closed

• The tension on knots is critical. If they are tied too tightly, the suture line may become ischaemic, leading to delayed healing or non-healing and an increased risk of wound infection. Equally, insufficient tension on the suture may result in failure to appose the wound edges or inadequate haemostasis.

Similar principles apply when using a continuous suture. A subcuticular continuous suture is preferred by some surgeons and avoids the small pinpoint scars at the site of entry and exit of interrupted sutures, or the ugly cross-hatching that results if sutures are tied too tightly or left in too long. Table 8.2 gives the suggested times for removal of sutures. Cosmetic results as good as those achieved by subcuticular suturing can be obtained by removing sutures in half the times listed in Table 8.2 and by replacing them with adhesive strips (e.g. Steristrip). Skin stapling is commonly used for closure of wounds at any site, as it can be undertaken rapidly. The staples are supplied in disposable cartridges for single patient use and are easily removed.

Table 8.2 Times recommended for removal of sutures

| 4 days | |

| 7 days | |

| 7–10 days | |

| 7 days | |

| 10–14 days |

Airway procedures

Maintaining the airway

Procedure

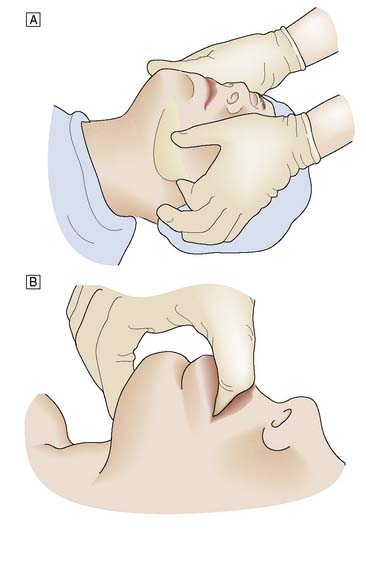

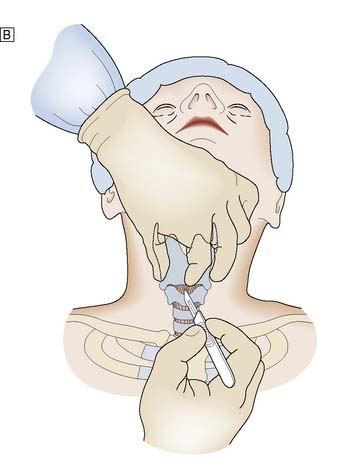

When the patient has to be kept supine, the neck should be extended. The mouth is opened slightly and the mandible pulled firmly forward by pressure applied behind both angles of the jaw. The mandible is held in this position by closing the mouth and using the teeth as a splint. Forward pressure is maintained behind the angles of the jaw (jaw-thrust manoeuvre) or submentally (chin-lift manoeuvre), avoiding pressure on the soft tissues (Fig. 8.1). In some cases, particularly in edentulous patients, an oropharyngeal airway helps to maintain a patent airway.

The laryngeal mask airway

Procedure

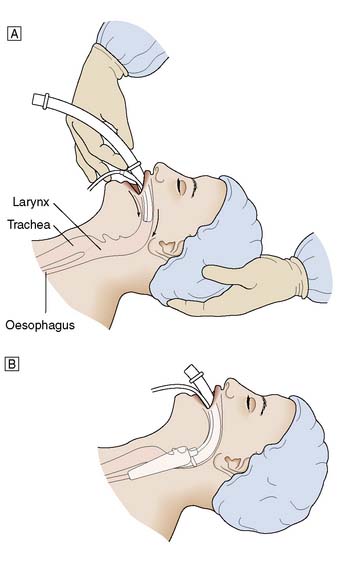

For men a size 4 is suitable, and for women a size 3, with smaller sizes being available for children. The cuff should be deflated and lubricated with gel. The patient’s head is maintained in an extended position using the left hand, and the airway is held in the right hand and introduced into the mouth (Fig. 8.2). The airway is passed backwards over the tongue until resistance is felt. It should then be at the level of the larynx. The cuff is inflated and the airway should be seen to rise slightly out of the mouth. Position is confirmed by the ability to ventilate the lungs.

Endotracheal intubation

Procedure

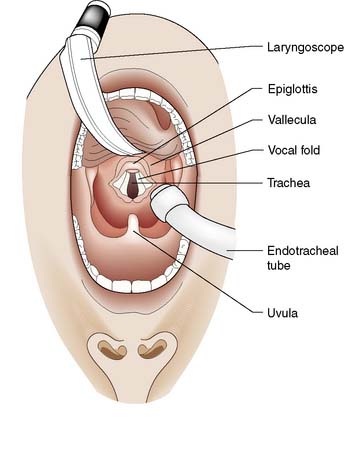

The laryngoscope is held in the left hand; its blade is inserted into the right side of the patient’s mouth and passed backwards along the side of the tongue into the oropharynx. The blade is designed to push the tongue over to the left side of the mouth. Care is taken to avoid damage to the lips and teeth. The laryngoscope is pulled upwards and forwards, not used as a lever, to lift the tongue and jaw and reveal the epiglottis (Fig. 8.3). The blade is then advanced to the base of the epiglottis and the laryngoscope pulled further upwards and forwards to reveal the vocal cords.

Surgical airway

Procedure

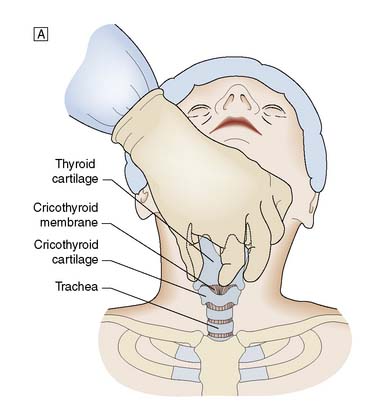

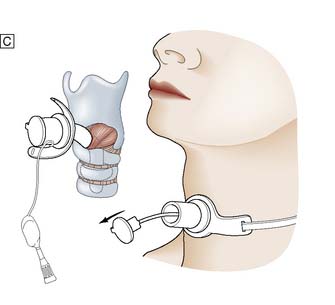

It is important to check all equipment and connections before starting. With the patient in the supine position and the neck in a neutral position, the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple) and cricoid cartilage are palpated. The cricothyroid membrane lies between the lower border of the thyroid cartilage and the upper border of the cricoid cartilage. The skin is cleansed with antiseptic solution and local anaesthetic infiltrated into the skin, if the patient is conscious. The thyroid cartilage is stabilized with the left hand and a small transverse skin incision made over the cricothyroid membrane. The blade of the scalpel is inserted through the membrane and then rotated through 90° to open the airway. An artery clip or tracheal spreader may be inserted to enlarge the opening enough to admit a cuffed endotracheal or tracheostomy tube (Fig. 8.4). The central trocar of the tube is removed and the tube connected to a bag-valve or ventilator circuit. The cuff is then inflated and air entry to each side of the chest is checked. The tube is secured to prevent dislodgement.

Thoracic procedures

Intercostal tube drainage

Procedure

If a low lateral approach is to be used, reference should be made to the chest X-ray to ensure that the drain will not be inserted subdiaphragmatically. A strict aseptic technique must be used. The skin, intercostal muscles and pleura are infiltrated with local anaesthetic. If a rib is encountered by the needle, the tip is ‘walked’ up the rib to enter the pleura above the rib edge. The depth at which the pleural space is entered is determined by aspiration with the syringe. A 3 cm horizontal incision is now made in the skin. A tract is developed by blunt dissection through the subcutaneous tissues and the intercostal muscles are separated just superior to the top of the rib to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundle. The parietal pleura is punctured with the tip of a pair of artery forceps and a gloved finger is inserted into the pleural cavity (Fig. 8.5). This ensures the incision is correctly placed, prevents injury to other organs, and permits any adhesions or clots to be cleared. The trocar is removed from the thoracostomy tube, the proximal end is clamped, and the tube is advanced into the pleural space to the desired length. The tube is sutured to the skin with a heavy suture to prevent accidental dislodgement. A ‘Z’ suture is placed around the incision, wrapped tightly around the drainage tube and tied, thus securing the tube. A sterile dressing and an adhesive bandage are applied to form an airtight seal and prevent aspiration of air around the tube. The drainage tube is attached to an underwater drainage system and a chest X-ray is then obtained. Low-pressure suction may be applied to the drainage bottle to assist drainage or re-expansion of the lung.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree