PQ

Pallor

Pallor is abnormal paleness or loss of skin color, which may develop suddenly or gradually. Although generalized pallor affects the entire body, it’s most apparent on the face, conjunctiva, oral mucosa, and nail beds. Localized pallor commonly affects a single limb.

How easily pallor is detected varies with skin color and the thickness and vascularity of underlying subcutaneous tissue. At times, it’s merely a subtle lightening of skin color that may be difficult to detect in dark-skinned people; sometimes it’s evident only on the conjunctiva and oral mucosa.

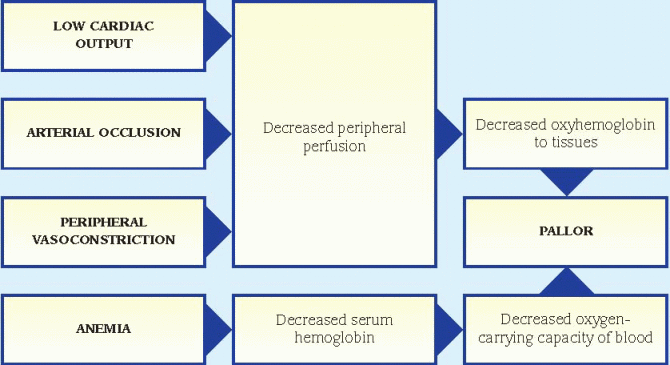

Pallor may result from decreased peripheral oxyhemoglobin or decreased total oxyhemoglobin. The former reflects diminished peripheral blood flow associated with peripheral vasoconstriction or arterial occlusion or with low cardiac output. (Transient peripheral vasoconstriction may occur with exposure to cold, causing nonpathologic pallor.) The latter usually results from anemia, the chief cause of pallor. (See How pallor develops, page 514.)

If generalized pallor suddenly develops, quickly look for signs of shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension, oliguria, and decreased level of consciousness. Prepare to rapidly infuse fluids or blood. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.

If generalized pallor suddenly develops, quickly look for signs of shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension, oliguria, and decreased level of consciousness. Prepare to rapidly infuse fluids or blood. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient’s condition permits, take a complete history. Does the patient or anyone in his family have a history of anemia or of a chronic disorder that might lead to pallor, such as renal failure, heart failure, or diabetes? Ask about the patient’s diet, particularly his intake of green vegetables.

Explore the pallor more fully. Find out when the patient first noticed it. Is pallor constant or intermittent? Does it occur when he’s exposed to the cold? Does it occur when he’s under emotional stress? Explore associated signs and symptoms, such as dizziness, fainting, orthostasis, weakness and fatigue on exertion, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, menstrual irregularities, or loss of libido. If the pallor is confined to one or both legs, ask the patient if walking is painful. Do his legs feel cold or numb? If the pallor is confined to his fingers, ask about tingling and numbness.

Start the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs. Be sure to check for orthostatic hypotension. Auscultate the heart for gallops and murmurs and the lungs for crackles. Check the patient’s skin temperature—cold extremities commonly occur with vasoconstriction or arterial occlusion. Note skin ulceration. Examine the abdomen for splenomegaly. Palpate peripheral pulses. An absent pulse in a pale extremity may indicate arterial occlusion, whereas a weak pulse may indicate low cardiac output.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Anemia. Typically, pallor develops gradually with this disorder. The patient’s skin may also appear sallow or grayish. Other effects include fatigue, dyspnea, tachycardia, bounding pulse, atrial gallop, systolic bruit over the carotid arteries and, possibly, crackles and bleeding tendencies.

♦ Arterial occlusion (acute). Pallor develops abruptly in the extremity with the occlusion, which usually results from an embolus. A line of demarcation develops, separating the cool, pale, cyanotic, and mottled skin below the occlusion from the normal skin above it. Accompanying the pallor may be severe pain, intense intermittent claudication, paresthesia, and paresis in the affected extremity. Absent pulses and increased capillary refill time below the occlusion are also characteristic.

♦ Arterial occlusive disease (chronic). With this disorder, pallor is specific to an extremity— usually one leg, but occasionally, both legs or an arm. It develops gradually from obstructive arteriosclerosis or a thrombus and is aggravated by elevating the extremity. Associated findings include intermittent claudication, weakness, cool skin, diminished pulses in the extremity and, possibly, ulceration and gangrene.

♦ Cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiac arrhythmias that seriously reduce cardiac output, such as complete heart block and attacks of tachyarrhythmia, may cause acute onset of pallor. Other features include irregular, rapid, or slow pulse; dizziness; weakness and fatigue; hypotension; confusion; palpitations; diaphoresis; oliguria; and, possibly, loss of consciousness.

♦ Frostbite. Pallor is localized to the frostbitten area, such as the feet, hands, or ears. Typically, the area feels cold, waxy and, perhaps, hard in deep frostbite. The skin doesn’t blanch and sensation may be absent. As the area thaws, the skin turns purplish blue. Blistering and gangrene may then follow if the frostbite was severe.

♦ Orthostatic hypotension. With this condition, pallor occurs abruptly on rising from a recumbent position to a sitting or standing position. A precipitous drop in blood pressure, an increase in heart rate, and dizziness are also characteristic. At times, the patient loses consciousness for several minutes.

♦ Raynaud’s disease. Pallor of the fingers upon exposure to cold or stress is a hallmark of this vascular disease. Typically, the fingers abruptly turn pale, then cyanotic; with rewarming, they become red and paresthetic. With chronic disease, ulceration may occur.

♦ Shock. Two forms of shock initially cause acute onset of pallor and cool, clammy skin. With hypovolemic shock, other early signs and

symptoms include restlessness, thirst, slight tachycardia, and tachypnea. As shock progresses, the skin becomes increasingly clammy, pulse becomes more rapid and thready, and hypotension develops with narrowing pulse pressure. Other signs and symptoms include oliguria, subnormal body temperature, and decreased level of consciousness. With cardiogenic shock, the signs and symptoms are similar, but usually more profound.

symptoms include restlessness, thirst, slight tachycardia, and tachypnea. As shock progresses, the skin becomes increasingly clammy, pulse becomes more rapid and thready, and hypotension develops with narrowing pulse pressure. Other signs and symptoms include oliguria, subnormal body temperature, and decreased level of consciousness. With cardiogenic shock, the signs and symptoms are similar, but usually more profound.

♦ Vasopressor syncope. Sudden onset of pallor immediately precedes or accompanies loss of consciousness during syncopal attacks. These common fainting spells may be triggered by emotional stress or pain and usually last only a few seconds or minutes. Before loss of consciousness, the patient may exhibit diaphoresis, nausea, yawning, hyperpnea, weakness, confusion, tachycardia, and dim vision. He then develops bradycardia, hypotension, a few clonic jerks, and dilated pupils with loss of consciousness.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

If the patient has chronic generalized pallor, prepare him for blood studies and, possibly, bone marrow biopsy. If the patient has localized pallor, he may require arteriography or other diagnostic studies to accurately determine the cause.

When pallor results from low cardiac output, administer blood and fluids and as well as a diuretic, a cardiotonic, and an antiarrhythmic, as needed. Frequently monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, electrocardiogram results, and hemodynamic status.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

In children, pallor stems from the same causes as it does in adults. It can also stem from a congenital heart defect or chronic lung disease.

Palpitations

Defined as a conscious awareness of one’s heartbeat, palpitations are usually felt over the precordium or in the throat or neck. The patient may describe them as pounding, jumping, turning, fluttering, or flopping, or as missing or skipping beats. Palpitations may be regular or irregular, fast or slow, paroxysmal or sustained.

Although usually insignificant, palpitations may result from a cardiac or metabolic disorder and from the effects of certain drugs. Nonpathologic palpitations may occur with a newly implanted prosthetic valve because the valve’s clicking sound heightens the patient’s awareness of his heartbeat. Transient palpitations may accompany emotional stress (such as fright, anger, or anxiety) or physical stress (such as exercise and fever). They can also accompany use of stimulants, such as tobacco and caffeine.

To help characterize the palpitations, ask the patient to simulate their rhythm by tapping his finger on a hard surface. An irregular “skipped beat” rhythm points to premature ventricular contractions, whereas an episodic racing rhythm that begins and ends abruptly suggests paroxysmal atrial tachycardia.

If the patient complains of palpitations, ask him about dizziness and shortness of breath. Inspect for pale, cool, clammy skin. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting hypotension and irregular or abnormal pulse. If these signs are present, suspect cardiac arrhythmia. Prepare to begin cardiac monitoring and, if necessary, synchronized cardioversion. Start an I.V. catheter to administer an antiarrhythmic, if needed.

If the patient complains of palpitations, ask him about dizziness and shortness of breath. Inspect for pale, cool, clammy skin. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting hypotension and irregular or abnormal pulse. If these signs are present, suspect cardiac arrhythmia. Prepare to begin cardiac monitoring and, if necessary, synchronized cardioversion. Start an I.V. catheter to administer an antiarrhythmic, if needed.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient isn’t in distress, perform a complete cardiac history and physical examination. Ask if he has a cardiovascular or pulmonary disorder, which may produce arrhythmias. Does the patient have a history of hypertension or hypoglycemia? Be sure to obtain a drug history. Has the patient recently started cardiac glycoside therapy? Ask about caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol consumption.

Explore associated symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, and angina. Auscultate for gallops, murmurs, and abnormal breath sounds.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Anemia. Palpitations may occur with anemia, especially on exertion. Pallor, fatigue, and dyspnea are also common. Associated signs include a systolic ejection murmur, bounding pulse, tachycardia, crackles, an atrial gallop, and a systolic bruit over the carotid arteries.

♦ Anxiety attack (acute). Anxiety is the most common cause of palpitations in children and adults. With this disorder, palpitations may be accompanied by diaphoresis, facial flushing, trembling, and an impending sense of doom. Almost invariably, the patient hyperventilates,

which may lead to dizziness, weakness, and syncope. Other typical findings include tachycardia, precordial pain, shortness of breath, restlessness, and insomnia.

which may lead to dizziness, weakness, and syncope. Other typical findings include tachycardia, precordial pain, shortness of breath, restlessness, and insomnia.

♦ Cardiac arrhythmias. Paroxysmal or sustained palpitations may be accompanied by dizziness, weakness, and fatigue. The patient may also experience an irregular, rapid, or slow pulse rate; decreased blood pressure; confusion; pallor; oliguria; and diaphoresis.

♦ Hypertension. With this disorder, the patient may be asymptomatic or may complain of sustained palpitations alone or with headache, dizziness, tinnitus, and fatigue. His blood pressure typically exceeds 140/90 mm Hg. He may also experience nausea and vomiting, seizures, and decreased level of consciousness (LOC).

♦ Hypocalcemia. Typically, this disorder produces palpitations, weakness, and fatigue. It progresses from paresthesia to muscle tension and carpopedal spasms. The patient may also exhibit muscle twitching, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, chorea, and positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs.

♦ Hypoglycemia. When blood glucose levels drop significantly, the sympathetic nervous system triggers adrenaline production. This may cause sustained palpitations, which may be accompanied by fatigue, irritability, hunger, cold sweats, tremors, tachycardia, anxiety, and headache. Eventually the patient may develop central nervous system reactions. These include blurred or double vision, muscle weakness, hemiplegia, and altered LOC.

♦ Mitral prolapse. This valvular disorder may cause paroxysmal palpitations accompanied by sharp, stabbing, or aching precordial pain. The hallmark of this disorder is a midsystolic click followed by an apical systolic murmur. Associated signs and symptoms may include dyspnea, dizziness, severe fatigue, migraine headache, anxiety, paroxysmal tachycardia, crackles, and peripheral edema.

♦ Mitral stenosis. Early features of this valvular disorder typically include sustained palpitations accompanied by exertional dyspnea and fatigue. Auscultation also reveals a loud S1 or opening snap, and a rumbling diastolic murmur at the apex. Patients may also experience related signs and symptoms, such as an atrial gallop and, with advanced mitral stenosis, orthopnea, dyspnea at rest, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, ascites, hepatomegaly, and atrial fibrillations.

♦ Pheochromocytoma. This rare adrenal medulla tumor causes episodic hypermetabolism, commonly associated with paroxysmal palpitations. The cardinal sign of pheochromocytoma is dramatically elevated blood pressure, which may be sustained or paroxysmal. Associated signs and symptoms include tachycardia, headache, chest or abdominal pain, diaphoresis, warm and pale or flushed skin, paresthesia, tremors, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, and anxiety.

♦ Sick sinus syndrome. A patient with this disorder may experience palpitations, as well as bradycardia, tachycardia, chest pain, syncope, and heart failure.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. A characteristic symptom of this disorder, sustained palpitations may be accompanied by tachycardia, dyspnea, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, nervousness, diaphoresis, heat intolerance and, possibly, exophthalmos and an enlarged thyroid. The patient may also experience an atrial or ventricular gallop.

♦ Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Seen in children and adolescents, this disorder results in recurrent palpitations and frequent episodes of paroxysmal tachycardia.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Palpitations may result from drugs that precipitate cardiac arrhythmias or increase cardiac output, such as cardiac glycosides; sympathomimetics such as cocaine; ganglionic blockers; beta-adrenergic blockers; calcium channel blockers; atropine; and minoxidil.

♦ Exercise. Exercise can normally cause palpitations, as well as in patients with coronary heart disease, hypertension, mitral valve prolapse, and cardiomegaly.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as an electrocardiogram and Holter monitoring. Remember that even mild palpitations can cause the patient much concern. Maintain a quiet, comfortable environment to minimize anxiety and perhaps decrease palpitations.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Palpitations in children commonly result from fever and congenital heart defects, such as patent ductus arteriosus and septal defects. Because many children can’t describe this complaint, focus your attention on objective measurements, such as cardiac monitoring, physical examination, and laboratory tests.

Papular rash

A papular rash consists of small, raised, circumscribed —and perhaps discolored (red to purple)— lesions known as papules. It may erupt anywhere on the body in various configurations and may be acute or chronic. Papular rashes characterize many cutaneous disorders; they may also result from allergy and from infectious, neoplastic, and systemic disorders. (To compare papules with other skin lesions, see Recognizing common skin lesions, pages 518 and 519.)

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Your first step is to fully evaluate the papular rash: Note its color, configuration, and location on the patient’s body. Find out when it erupted. Has the patient noticed any changes in the rash since then? Is it itchy or burning, or painful or tender? Have him describe associated signs and symptoms, such as fever, headache, and GI distress.

Next, obtain a medical history, including allergies, previous rashes or skin disorders, infections, childhood diseases, sexual history, including any sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and cancers. Has the patient recently been bitten by an insect or rodent or been exposed to anyone with an infectious disease? Finally, obtain a complete drug history.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acne vulgaris. With this disorder, rupture of enlarged comedones produces inflamed—and perhaps, painful and pruritic—papules, pustules, nodules, or cysts on the face and sometimes the shoulders, chest, and back.

♦ Anthrax (cutaneous). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Cutaneous anthrax occurs when the bacterium enters a cut or abrasion on the skin. The infection begins as a small, painless, or pruritic macular or papular lesion resembling an insect bite. Within 1 to 2 days it develops into a vesicle and then a painless ulcer with a characteristic black, necrotic center. Lymphadenopathy, malaise, headache, or fever may develop.

♦ Dermatitis (perioral). This inflammatory disorder causes an erythematous eruption of discrete, tiny papules and pustules on the nasolabial fold, chin, and upper lip area. The lesions may be pruritic and painful.

♦ Dermatomyositis. Gottron’s papules—flat, violet-colored lesions on the dorsa of the finger joints and the nape of the neck and shoulders— are pathognomonic of this disorder, as is the dusky lilac discoloration of periorbital tissue and lid margins (heliotrope edema). These signs may be accompanied by a transient, erythematous, macular rash in a malar distribution on the face and sometimes on the scalp, forehead, neck, upper torso, and arms. This rash may be preceded by symmetrical muscle soreness and weakness in the pelvis, upper extremities, shoulders, neck and, possibly, the face (polymyositis).

♦ Erythema migrans. Transmitted through a tick bite, this systemic disorder is characterized by a papular or macular rash starting from a single lesion (usually on the leg) that spreads at the margins while clearing centrally. The rash commonly appears on the thighs, trunk, or upper arms and is the classic early sign of Lyme disease, but about 25% of patients don’t develop this skin manifestation. It may be accompanied by fever, chills, headache, malaise, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, backache, knee pain, and stiff neck.

♦ Follicular mucinosis. With this cutaneous disorder, perifollicular papules or plaques are accompanied by prominent alopecia.

♦ Fox-Fordyce disease. This chronic disorder is marked by pruritic papules on the axillae, pubic area, and areolae associated with apocrine sweat gland inflammation. Sparse hair growth in these areas is also common.

♦ Gonococcemia. With this chronic STD, sporadic eruption of an erythematous macular rash is characteristic, although fistulas and petechiae may appear. The rash typically affects the distal extremities (palms and soles) and rapidly becomes maculopapular, vesiculopustular and, commonly, hemorrhagic. Bullae may form. The mature lesion is raised; has a gray, necrotic center; and is surrounded by erythema. Typically, it

heals in 3 to 4 days. Eruptions are commonly accompanied by fever and joint pain.

heals in 3 to 4 days. Eruptions are commonly accompanied by fever and joint pain.

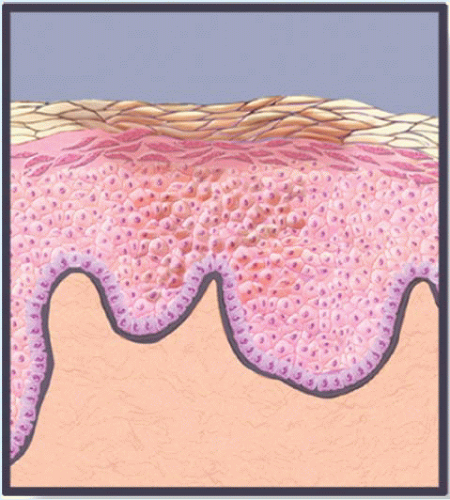

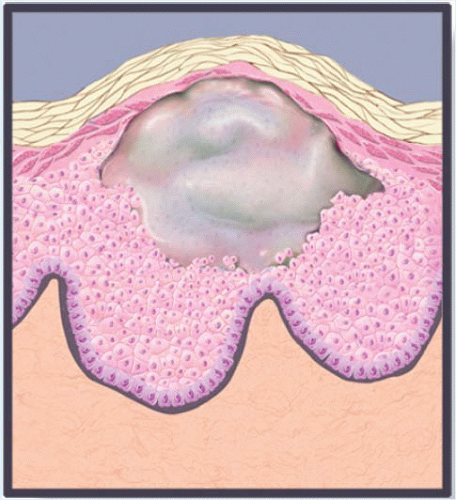

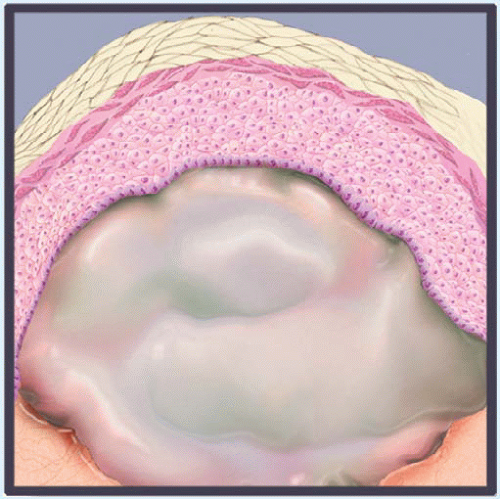

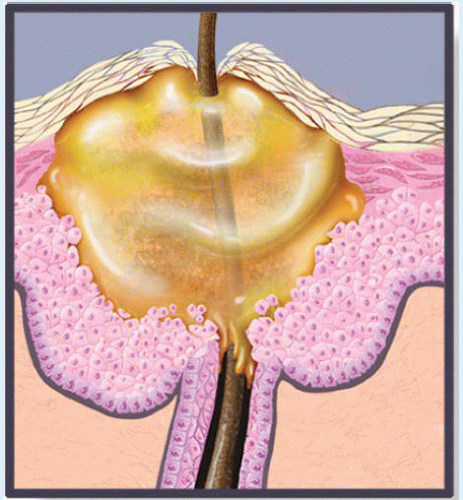

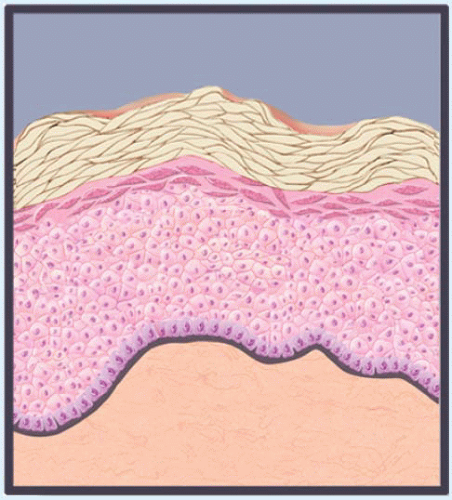

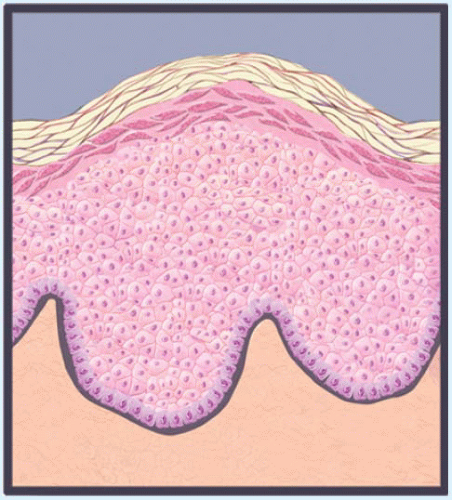

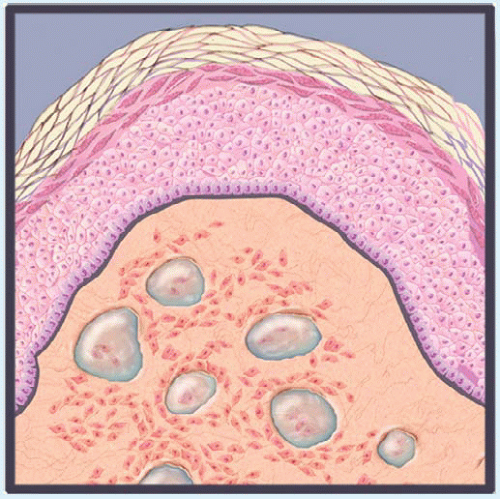

Recognizing common skin lesions

A small (usually less than 1 cm in diameter), flat blemish or discoloration that can be brown, tan, red, or white and has same texture as surrounding skin

A raised, thin-walled blister greater than 0.5 cm in diameter, containing clear or serous fluid

A small (less than 0.5 cm in diameter), thinwalled, raised blister containing clear, serous, purulent, or bloody fluid

A circumscribed, pus- or lymph-filled, elevated lesion that varies in diameter and may be firm or soft, and white or yellow

A slightly raised, firm lesion of variable size and shape, surrounded by edema; skin may be red or pale

A small, firm, circumscribed, elevated lesion 1 to 2 cm in diameter with possible skin discoloration

A small, solid, raised lesion less than 1 cm in diameter, with red to purple skin discoloration

A solid, raised mass usually larger than 2 cm in diameter with possible skin discoloration

♦ Granuloma annulare. This benign, chronic disorder produces papules that usually coalesce to form plaques. The papules spread peripherally to form a ring with a normal or slightly depressed center. They usually appear on the feet, legs, hands, or fingers, and may be pruritic or asymptomatic.

♦ Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Acute infection with the HIV retrovirus typically causes a generalized maculopapular rash. Other signs and symptoms include fever, malaise, sore throat, and headache. Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly may also occur. Most patients don’t recall these symptoms of acute infection.

♦ Insect bites. Salivary secretions from insect bites—especially ticks, lice, flies, and mosquitoes —may produce an allergic reaction associated with a papular, macular, or petechial rash. The rash is usually accompanied by nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, headache, lymphadenopathy, nausea, and vomiting.

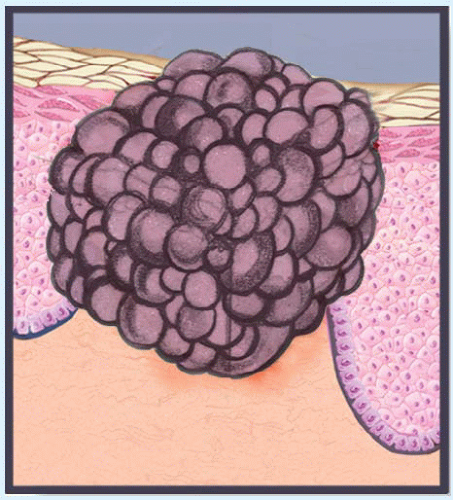

♦ Kaposi’s sarcoma. This neoplastic disorder is characterized by purple or blue papules or macules of vascular origin on the skin, mucous membranes, and viscera. These lesions

decrease in size with firm pressure and then return to their original size within 10 to 15 seconds. They may become scaly and ulcerate with bleeding.

decrease in size with firm pressure and then return to their original size within 10 to 15 seconds. They may become scaly and ulcerate with bleeding.

Multiple variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma are known; most individuals are immunocompromised in some way, especially those with HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Human herpes virus-8 (HHV-8) has been strongly implicated as a cofactor in the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

♦ Leprosy. This chronic infectious disorder produces various skin lesions. Early papular or macular lesions are erythematous, hypopigmented, and symmetrical (with lepromatous leprosy) or asymmetrical (with tuberculoid leprosy). The lesions may spread over the entire skin surface. Later, plaques and nodules form, especially on the ear lobes, nose, eyebrows, and forehead. Associated findings include hypoesthesia or anesthesia, anhidrosis, and dry, scaly skin in affected areas; enlarged, palpable peripheral nerves with severe neuralgia; and muscle atrophy and contractures.

♦ Lichen amyloidosis. This idiopathic cutaneous disorder produces discrete, firm, hemispherical, pruritic papules on the anterior tibiae. Papules may be brown or yellow, smooth or scaly.

♦ Lichen planus. Discrete, flat, angular or polygonal, violet papules, commonly marked with white lines or spots, are characteristic of this disorder. The papules may be linear or coalesce into plaques and usually appear on the lumbar region, genitalia, ankles, anterior tibiae, and wrists. Lesions usually develop first on the buccal mucosa as a lacy network of white or gray threadlike papules or plaques. Pruritus, distorted fingernails, and atrophic alopecia commonly occur.

♦ Monkeypox. Usually preceded 1 to 3 days by a fever, a papular rash is a characteristic sign of monkeypox. The rash is often blisterlike and can follow these stages: vesiculation, postulation, umbilication, and crusting. Frequently beginning on the face and spreading to the trunk and extremities, the rash may be either localized or generalized. Other accompanying symptoms in humans include lymphadenopathy, chills, throat pain, and muscle aches. Most humans recover within 2 to 4 weeks.

♦ Mononucleosis (infectious). A maculopapular rash that resembles rubella is an early sign of this infection in 10% of patients. The rash is typically preceded by headache, malaise, and fatigue. It may be accompanied by sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, and fluctuating temperature with an evening peak of 101° to 102° F (38.3° to 38.9° C). Splenomegaly and hepatomegaly may also develop.

♦ Mycosis fungoides. Stage I (premycotic stage) of this rare, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is marked by the eruption of erythematous, pruritic macules on the trunk and extremities. In stage II, these lesions coalesce into pruritic papules and plaques, and nodes become irregular. Stage III is evidenced by large, irregular, brown to red tumors that ulcerate and are painful and itchy.

♦ Necrotizing vasculitis. With this systemic disorder, crops of purpuric, but otherwise asymptomatic, papules are typical. Some patients also develop low-grade fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and abdominal pain.

♦ Parapsoriasis (chronic). This disorder mimics psoriasis, producing small to moderately sized asymptomatic papules with a thin, adherent scale, primarily on the trunk, hands, and feet.

♦ Pityriasis rosea. This disorder begins with an erythematous “herald patch”—a slightly raised, oval lesion about 2 to 6 cm in diameter that may appear anywhere on the body. A few days to weeks later, yellow to tan or erythematous patches with scaly edges appear on the trunk, arms, and legs, commonly erupting along body cleavage lines in a characteristic “pine tree” pattern. These patches may be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic, are 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter, and typically improve with moderate skin exposure to sunlight. This treatment should be used cautiously, however, to avoid sunburn.

♦ Pityriasis rubra pilaris. This rare chronic disorder initially produces scaling seborrhea on the scalp that spreads to the face and ears. Scaly red patches then develop on the palms and soles; these patches thicken, become keratotic, and may develop painful fissures. Later, follicular papules erupt on the hands and forearms and then spread over wide areas of the trunk, neck, and extremities. These papules coalesce into large, scaly, erythematous plaques. Striated fingernails may appear.

♦ Polymorphic light eruption. Abnormal reactions to light may produce papular, vesicular, or nodular rashes on sun-exposed areas. Other symptoms include pruritus, headache, and malaise.

♦ Psoriasis. This common chronic disorder begins with small, erythematous papules on the scalp, chest, elbows, knees, back, buttocks, and genitalia. These papules are sometimes pruritic and painful. Eventually they enlarge and coalesce, forming elevated, red, scaly plaques covered by characteristic silver scales, except in moist areas such as the genitalia. These scales may flake off easily or thicken, covering the plaque. Associated features include pitted fingernails and arthralgia.

♦ Rat bite fever. A maculopapular or petechial rash develops on the palms and soles several weeks after a bite from an infected rodent. Other findings typically include pain, redness, and swelling at the bite site; tender regional lymph nodes; fever with chills; malaise; headache; and myalgia.

♦ Rosacea. This hyperemic disorder is characterized by persistent erythema, telangiectasia, and recurrent eruption of papules and pustules on the forehead, malar areas, nose, and chin. Eventually, eruptions occur more frequently and erythema deepens. Rhinophyma may occur in severe cases.

♦ Sarcoidosis. This multisystem granulomatous disorder may produce crops of small, erythematous or yellow-brown papules around the eyes and mouth and on the nose, nasal mucosa, and upper back. Associated findings include dyspnea with a nonproductive cough, fatigue, arthralgia, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, vision loss, and dysphagia.

♦ Seborrheic keratosis. With this cutaneous disorder, benign skin tumors begin as small, yellow-brown papules on the chest, back, or abdomen, eventually enlarging and becoming deeply pigmented. However, in blacks, these papules may remain small and affect only the malar part of the face (dermatosis papulosa nigra).

♦ Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms include high fever, malaise, prostration, severe headache, backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days the pustules form a crust, and later the scab separates from the skin leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

♦ Syphilis. A discrete, reddish brown, mucocutaneous rash and general lymphadenopathy herald the onset of secondary syphilis. The rash may be papular, macular, pustular, or nodular. It typically erupts between rolls of fat on the trunk and proximally on the arms, palms, soles, face, and scalp. Lesions in warm, moist areas enlarge and erode, producing highly contagious, pink or grayish white condylomata lata. The patient may also experience mild headache, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, nausea and vomiting, sore throat, low-grade fever, temporary alopecia, and brittle, pitted nails.

♦ Syringoma. With this disorder, adenoma of the sweat glands produces a yellowish or erythematous papular rash on the face (especially the eyelids), neck, and upper chest.

♦ Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE is characterized by a “butterfly rash” of erythematous maculopapules or discoid plaques that appears in a malar distribution across the nose and cheeks. Similar rashes may appear elsewhere, especially on exposed body areas. Other cardinal features include photosensitivity and nondeforming arthritis, especially in the hands, feet, and large joints. Common effects are patchy alopecia, mucous membrane ulceration, low-grade or spiking fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, dyspnea, tachycardia, hematuria, headache, and irritability.

♦ Typhus. Typhus is a rickettsial disease transmitted to humans by fleas, mites, or body louse. Initial symptoms include headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise, followed by an abrupt onset of chills, fever, nausea, and vomiting. A maculopapular rash may be present in some cases.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Transient maculopapular rashes, usually on the trunk, may accompany reactions to many drugs, including antibiotics, such as tetracycline, ampicillin, cephalosporins, and sulfonamides; benzodiazepines such as diazepam; lithium; gold salts; allopurinol; isoniazid; and salicylates.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Apply cool compresses or an antipruritic lotion. Administer an antihistamine for allergic reactions and an antibiotic for infection.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Common causes of papular rashes in children are infectious diseases, such as molluscum contagiosum and scarlet fever; scabies; insect bites; allergies and drug reactions; and miliaria, which occurs in three forms, depending on the depth of sweat gland involvement.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

In bedridden elderly patients, the first sign of pressure ulcers is commonly an erythematous area, sometimes with firm papules. If not properly managed, these lesions progress to deep ulcers and can lead to death.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Advise the patient to keep his skin clean and dry, to wear loose-fitting, nonirritating clothing, and to avoid scratching the rash. Instruct him to promptly report changes in the rash’s color, size, or configuration as well as the onset of itching or bleeding. Tell him to avoid excessive exposure to direct sunlight and to apply a protective sunscreen before going outdoors.

Warn patients with chronic conditions (such as SLE, psoriasis, or sarcoidosis) about the typical skin rashes that can develop. Tell them that these rashes can be an early sign of disease flare-up and that they should seek prompt treatment to prevent serious complications.

Paralysis

Paralysis, the total loss of voluntary motor function, results from severe cortical or pyramidal tract damage. It can occur with a cerebrovascular disorder, degenerative neuromuscular disease, trauma, tumor, or central nervous system infection. Acute paralysis may be an early indicator of a life-threatening disorder, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Paralysis can be local or widespread, symmetrical or asymmetrical, transient or permanent, and spastic or flaccid. It’s commonly classified according to location and severity as paraplegia (sometimes transient paralysis of the legs), quadriplegia (permanent paralysis of the arms, legs, and body below the level of the spinal lesion), or hemiplegia (unilateral paralysis of varying severity and permanence). Incomplete paralysis with profound weakness (paresis) may precede total paralysis in some patients.

If paralysis has developed suddenly, suspect trauma or an acute vascular insult. After ensuring that the patient’s spine is properly immobilized, quickly determine his level of consciousness (LOC) and take his vital signs. Elevated systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and bradycardia may signal increasing intracranial pressure (ICP). If possible, elevate the patient’s head 30 degrees to decrease ICP.

If paralysis has developed suddenly, suspect trauma or an acute vascular insult. After ensuring that the patient’s spine is properly immobilized, quickly determine his level of consciousness (LOC) and take his vital signs. Elevated systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and bradycardia may signal increasing intracranial pressure (ICP). If possible, elevate the patient’s head 30 degrees to decrease ICP.Evaluate respiratory status, and be prepared to administer oxygen, insert an artificial airway, or provide intubation and mechanical ventilation, as needed. To help determine the nature of the patient’s injury, ask him for an account of the precipitating events. If he’s unable to respond, try to find an eyewitness.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient is in no immediate danger, perform a complete neurologic assessment. Start with the history, relying on family members for information if necessary. Ask about the onset, duration, intensity, and progression of paralysis and about the events preceding its development. Focus medical history questions on the incidence of degenerative neurologic or neuromuscular disease, recent infectious illness, sexually transmitted disease, cancer, or recent injury. Explore related signs and symptoms, noting fever, headache, vision disturbances, dysphagia, nausea and vomiting, bowel or bladder dysfunction, muscle pain or weakness, and fatigue.

Next, perform a complete neurologic examination, testing cranial nerve, motor, and sensory function and deep tendon reflexes. Assess strength in all major muscle groups, and note any muscle atrophy. (See Testing muscle strength, pages 464 and 465.) Document all findings to serve as a baseline.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. This invariably fatal disorder produces spastic or flaccid paralysis in the body’s major muscle groups, eventually progressing to total paralysis. Earlier findings include progressive muscle weakness, fasciculations, and muscle atrophy, usually beginning in the arms and hands. Cramping and hyperreflexia are also common. Involvement of respiratory muscles and the brain stem produces dyspnea and possibly respiratory distress. Progressive cranial nerve paralysis causes dysarthria, dysphagia, drooling, choking, and difficulty chewing.

♦ Bell’s palsy. Bell’s palsy, a disease of cranial nerve VII, causes transient, unilateral facial muscle paralysis. The affected muscles sag and eyelid closure is impossible. Other signs include increased tearing, drooling, and a diminished or absent corneal reflex.

♦ Botulism. This bacterial toxin infection can cause rapidly descending muscle weakness that progresses to paralysis within 2 to 4 days after the ingestion of contaminated food. Respiratory muscle paralysis leads to dyspnea and respiratory arrest. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blurred or double vision, bilateral mydriasis, dysarthria, and dysphagia are some early findings.

♦ Brain abscess. Advanced abscess in the frontal or temporal lobe can cause hemiplegia accompanied by other late findings, such as ocular disturbances, unequal pupils, decreased LOC, ataxia, tremors, and signs of infection.

♦ Brain tumor. A tumor affecting the motor cortex of the frontal lobe may cause contralateral hemiparesis that progresses to hemiplegia. Onset is gradual, but paralysis is permanent without treatment. In early stages, frontal headache and behavioral changes may be the only indicators. Eventually, seizures, aphasia, and signs of increased ICP (decreased LOC and vomiting) develop.

♦ Conversion disorder. Hysterical paralysis, a classic symptom of conversion disorder, is characterized by the loss of voluntary movement

with no obvious physical cause. It can affect any muscle group, appears and disappears unpredictably, and may occur with histrionic behavior (manipulative, dramatic, vain, irrational) or a strange indifference.

with no obvious physical cause. It can affect any muscle group, appears and disappears unpredictably, and may occur with histrionic behavior (manipulative, dramatic, vain, irrational) or a strange indifference.

♦ Encephalitis. Variable paralysis develops in the late stages of this disorder. Earlier signs and symptoms include rapidly decreasing LOC (possibly coma), fever, headache, photophobia, vomiting, signs of meningeal irritation (nuchal rigidity, positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs), aphasia, ataxia, nystagmus, ocular palsies, myoclonus, and seizures.

♦ Guillain-Barré syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by a rapidly developing, but reversible, ascending paralysis. It commonly begins as leg muscle weakness and progresses symmetrically, sometimes affecting even the cranial nerves, producing dysphagia, nasal speech, and dysarthria. Respiratory muscle paralysis may be life-threatening. Other effects include transient paresthesia, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and bowel and bladder incontinence.

♦ Head trauma. Cerebral injury can cause paralysis due to cerebral edema and increased intracranial pressure. Onset is usually sudden. Location and extent vary, depending on the injury. Associated findings also vary but include decreased LOC; sensory disturbances, such as paresthesia and loss of sensation; headache; blurred or double vision; nausea and vomiting; and focal neurologic disturbances.

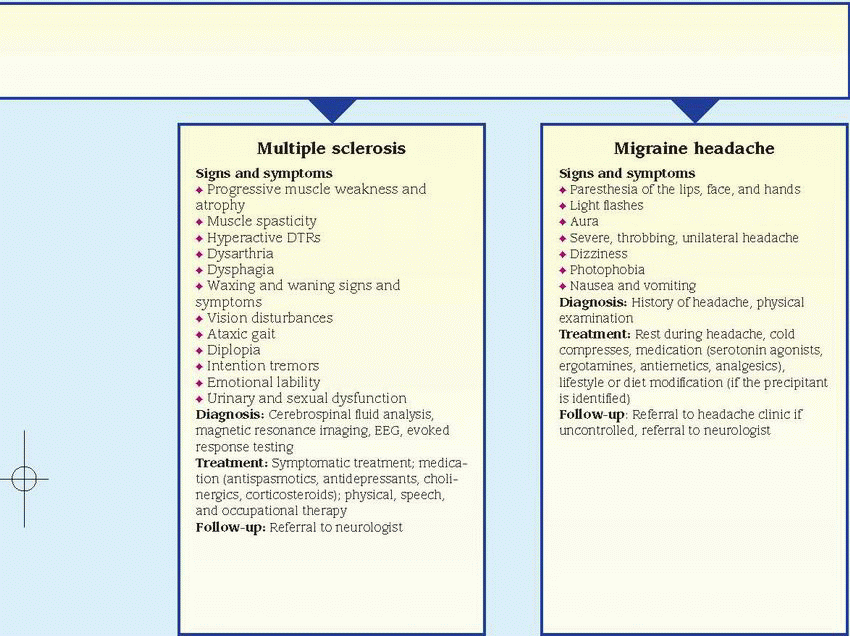

♦ Migraine headache. Hemiparesis, scotomas, paresthesia, confusion, dizziness, photophobia, or other transient symptoms may precede the onset of a throbbing unilateral headache and may persist after it subsides.

♦ Multiple sclerosis. With this disorder, paralysis commonly waxes and wanes until the later stages, when it may become permanent. Its extent can range from monoplegia to quadriplegia. In most patients, vision and sensory disturbances (paresthesia) are the earliest symptoms. Later findings are widely variable and may include muscle weakness and spasticity, nystagmus, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, gait ataxia, dysphagia, dysarthria, impotence, and constipation. Urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence may also occur.

♦ Myasthenia gravis. With this neuromuscular disease, profound muscle weakness and abnormal fatigability may produce paralysis of certain muscle groups. Paralysis is usually transient in early stages but becomes more persistent as the disease progresses. Associated findings depend on the areas of neuromuscular involvement; they include weak eye closure, ptosis, diplopia, lack of facial mobility, dysphagia, nasal speech, and frequent nasal regurgitation of fluids. Neck muscle weakness may cause the patient’s jaw to drop and his head to bob. Respiratory muscle involvement can lead to respiratory distress—dyspnea, shallow respirations, and cyanosis.

♦ Neurosyphilis. Irreversible hemiplegia may occur in the late stages of neurosyphilis. Dementia, cranial nerve palsies, tremors, and abnormal reflexes are other late findings.

♦ Parkinson’s disease. Tremors, bradykinesia, and lead-pipe or cogwheel rigidity are the classic signs of Parkinson’s disease. Extreme rigidity can progress to paralysis, particularly in the extremities. In most cases, paralysis resolves with prompt treatment of the disease.

♦ Peripheral nerve trauma. Severe injury to a peripheral nerve or group of nerves results in the loss of motor and sensory function in the innervated area. Muscles become flaccid and atrophied, and reflexes are lost. If transection isn’t complete, paralysis may be temporary.

♦ Peripheral neuropathy. Typically, this syndrome produces muscle weakness that may lead to flaccid paralysis and atrophy. Related effects include paresthesia, loss of vibration sensation, hypoactive or absent deep tendon reflexes, neuralgia, and skin changes such as anhidrosis.

♦ Poliomyelitis. This disorder can produce insidious, permanent flaccid paralysis and hypore-flexia. Sensory function remains intact, but the patient loses voluntary muscle control.

♦ Rabies. This acute disorder produces progressive flaccid paralysis, vascular collapse, coma, and death within 2 weeks of contact with an infected animal. Prodromal signs and symptoms —fever; headache; hyperesthesia; paresthesia, coldness, and itching at the bite site; photophobia; tachycardia; shallow respirations; and excessive salivation, lacrimation, and perspiration —develop almost immediately. Within 2 to 10 days, a phase of excitement begins, marked by agitation, cranial nerve dysfunction (pupil changes, hoarseness, facial weakness, ocular palsies), tachycardia or bradycardia, cyclic respirations, high fever, urine retention, drooling, and hydrophobia.

♦ Seizure disorders. Seizures, particularly focal seizures, can cause transient local paralysis (Todd’s paralysis). Any part of the body may be

affected, although paralysis tends to occur contralateral to the side of the irritable focus.

affected, although paralysis tends to occur contralateral to the side of the irritable focus.

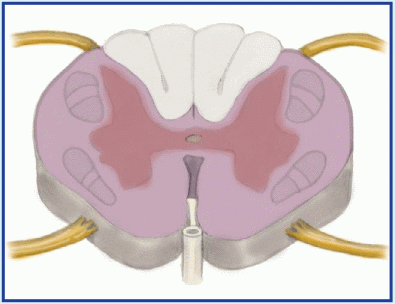

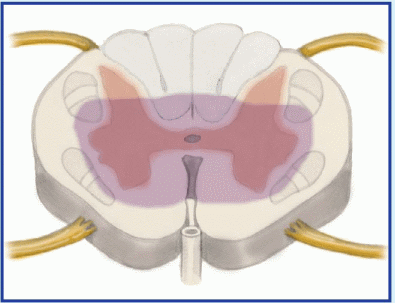

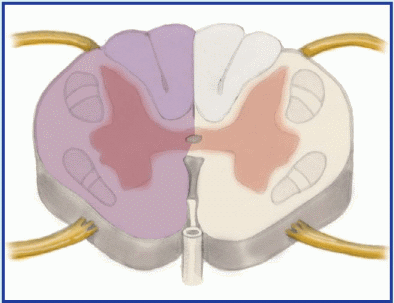

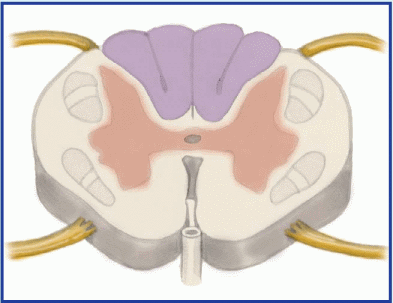

Understanding spinal cord syndromes

When a patient’s spinal cord is incompletely severed, he experiences partial motor and sensory loss. Most incomplete cord lesions fit into one of the syndromes described below.

|

Anterior cord syndrome, usually resulting from a flexion injury, causes motor paralysis and loss of pain and temperature sensation below the level of injury. Touch, proprioception, and vibration sensation are usually preserved.

|

Brown-Séquard syndrome can result from flexion, rotation, or penetration injury. It’s characterized by unilateral motor paralysis ipsilateral to the injury and loss of pain and temperature sensation contralateral to the injury.

|

Central cord syndrome is caused by hyperextension or flexion injury. Motor loss is variable and greater in the arms than in the legs; sensory loss is usually slight.

|

Posterior cord syndrome, produced by a cervical hyperextension injury, causes only a loss of proprioception and loss of light touch sensation. Motor function remains intact.

♦ Spinal cord injury. Complete spinal cord transection results in permanent spastic paralysis below the level of injury. Reflexes may return after spinal shock resolves. Partial transection causes variable paralysis and paresthesia, depending on the location and extent of injury. (See Understanding spinal cord syndromes.)

♦ Spinal cord tumors. Paresis, pain, paresthesia, and variable sensory loss may occur along the nerve distribution pathway served by the affected cord segment. Eventually, these symptoms may progress to spastic paralysis with hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (unless the tumor is in the cauda equina, which produces hyporeflexia) and, perhaps, bladder and bowel incontinence. Paralysis is permanent without treatment.

♦ Stroke. A stroke involving the motor cortex can produce contralateral paresis or paralysis. Onset may be sudden or gradual, and paralysis may be transient or permanent. Associated signs and symptoms vary widely and may include headache, vomiting, seizures, decreased LOC and mental acuity, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, contralateral paresthesia or sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, vision disturbances, emotional lability, and bowel and bladder dysfunction.

♦ Subarachnoid hemorrhage. This potentially life-threatening disorder can produce sudden paralysis. The condition may be temporary, resolving with decreasing edema, or permanent, if tissue destruction has occurred. Other acute effects are severe headache, mydriasis, photophobia, aphasia, sharply decreased LOC, nuchal rigidity, vomiting, and seizures.

♦ Syringomyelia. This degenerative spinal cord disease produces segmental paresis, leading to flaccid paralysis of the hands and arms. Reflexes are absent, and loss of pain and temperature sensation is distributed over the neck, shoulders, and arms in a capelike pattern.

♦ Thoracic aortic aneurysm. Occlusion of spinal arteries by a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm may cause sudden onset of transient bilateral paralysis. Severe chest pain radiating to the neck, shoulders, back, and abdomen and a sensation of tearing in the thorax are prominent symptoms. Related findings include syncope, pallor, diaphoresis, dyspnea, tachycardia, cyanosis, diastolic heart murmur, and abrupt loss of radial and femoral pulses or wide variations in pulses and blood pressure between arms and legs. Ironically, the patient appears to be in shock, and his systolic blood pressure is either normal or elevated.

♦ Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Episodic TIAs may cause transient unilateral paresis or paralysis accompanied by paresthesia, blurred or double vision, dizziness, aphasia, dysarthria, decreased LOC, and other site-dependent effects.

♦ West Nile encephalitis. This brain infection is caused by West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus endemic to Africa, the Middle East, western Asia, and the United States. Mild infections are common and include fever, headache, and body aches, which are sometimes accompanied by skin rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe infections are marked by headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional convulsions, paralysis and, rarely, death.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Therapeutic use of neuromuscular blockers, such as pancuronium, produces paralysis.

♦ Electroconvulsive therapy. This therapy can produce acute, but transient, paralysis.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because a paralyzed patient is particularly susceptible to complications of prolonged immobility, provide frequent position changes, meticulous skin care, and frequent chest physiotherapy. He may benefit from passive rangeof-motion exercises to maintain muscle tone, application of splints to prevent contractures, and the use of footboards or other devices to prevent footdrop. If his cranial nerves are affected, the patient will have difficulty chewing and swallowing. Provide a liquid or soft diet, and keep suction equipment on hand in case aspiration occurs. Feeding tubes or total parenteral nutrition may be necessary with severe paralysis. Paralysis and accompanying vision disturbances may make ambulation hazardous; provide a call light and show the patient how to call for help. As appropriate, arrange for physical, speech, or occupational therapy.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Although children may develop paralysis from an obvious cause—such as trauma, infection, or tumor—they may also develop it from a hereditary or congenital disorder, such as Tay-Sachs disease, Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, spina bifida, or cerebral palsy.

Paresthesia

Paresthesia is an abnormal sensation or combination of sensations—commonly described as numbness, prickling, or tingling—felt along peripheral nerve pathways; these sensations generally aren’t painful. Unpleasant or painful sensations, on the other hand, are termed dysesthesias. Paresthesia may develop suddenly or gradually and may be transient or permanent.

A common symptom of many neurologic disorders, paresthesia may also result from a systemic disorder or from a particular drug. It may reflect damage or irritation of the parietal lobe, thalamus, spinothalamic tract, or spinal or peripheral nerves—the neural circuit that transmits and interprets sensory stimuli.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

First, explore the paresthesia. When did the abnormal sensations begin? Have the patient describe their character and distribution. Ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as sensory loss and paresis or paralysis. Next, take a medical history, including neurologic, cardiovascular, metabolic, renal, and chronic inflammatory disorders, such as arthritis or lupus. Has the patient recently sustained a traumatic injury or had surgery or an invasive procedure that may have damaged peripheral nerves?

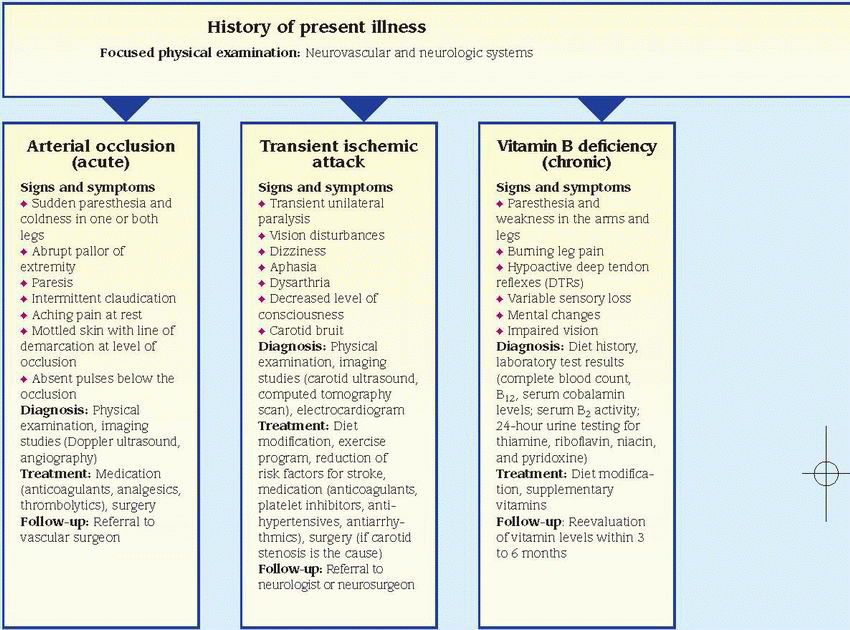

Focus the physical examination on the patient’s neurologic status. (See Differential diagnosis: Paresthesia.) Assess his level of consciousness (LOC) and cranial nerve function. Test muscle strength and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in limbs affected by paresthesia. Systematically evaluate light touch, pain, temperature, vibration, and position sensation. (See Testing for analgesia, pages 42 and 43.) Note skin color and temperature, and palpate pulses.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Arterial occlusion (acute). With this disorder, sudden paresthesia and coldness may develop in one or both legs with a saddle embolus. Paresis, intermittent claudication, and aching pain at rest are also characteristic. The extremity becomes mottled with a line of temperature and color demarcation at the level of occlusion. Pulses are absent below the occlusion, and capillary refill time is increased.

♦ Arteriosclerosis obliterans. This disorder produces paresthesia, intermittent claudication (most common symptom), diminished or absent popliteal and pedal pulses, pallor, paresis, and coldness in the affected leg.

♦ Arthritis. Rheumatoid or osteoarthritic changes in the cervical spine may cause paresthesia in the neck, shoulders, and arms. The lumbar spine occasionally is affected, causing paresthesia in one or both legs and feet.

♦ Brain tumor. Tumors affecting the sensory cortex in the parietal lobe may cause progressive contralateral paresthesia accompanied by

agnosia, apraxia, agraphia, homonymous hemianopsia, and loss of proprioception.

agnosia, apraxia, agraphia, homonymous hemianopsia, and loss of proprioception.

♦ Buerger’s disease. With this smoking-related inflammatory occlusive disorder, exposure to cold makes the feet cold, cyanotic, and numb; later, they redden, become hot, and tingle. Intermittent claudication, which is aggravated by exercise and relieved by rest, is also common. Other findings include weak peripheral pulses, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis and, later, ulceration, muscle atrophy, and gangrene.

♦ Diabetes mellitus. Diabetic neuropathy can cause paresthesia with a burning sensation in the hands and legs. Other findings include insidious, permanent anosmia, fatigue, polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, and polyphagia.

♦ Guillain-Barré syndrome. With this syndrome, transient paresthesia may precede muscle weakness, which usually begins in the legs and ascends to the arms and facial nerves. Weakness may progress to total paralysis. Other findings include dysarthria, dysphagia, nasal speech, orthostatic hypotension, bladder and bowel incontinence, diaphoresis, tachycardia and, possibly, signs of life-threatening respiratory muscle paralysis.

♦ Head trauma. Unilateral or bilateral paresthesia may occur when head trauma causes a concussion or contusion; however, sensory loss is more common. Other findings include variable paresis or paralysis, decreased LOC, headache, blurred or double vision, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and seizures.

♦ Heavy metal or solvent poisoning. Exposure to industrial or household products containing lead, mercury, thallium, or organophosphates may cause paresthesia of acute or gradual onset. Mental status changes, tremors, weakness, seizures, and GI distress are also common.

♦ Herniated disk. Herniation of a lumbar or cervical disk may cause acute or gradual onset of paresthesia along the distribution pathways of affected spinal nerves. Other neuromuscular effects include severe pain, muscle spasms, and weakness that may progress to atrophy unless herniation is relieved.

♦ Herpes zoster. An early symptom of this disorder, paresthesia occurs in the dermatome supplied by the affected spinal nerve. Within several days, this dermatome is marked by a pruritic, erythematous, vesicular rash associated with sharp, shooting, or burning pain.

♦ Hyperventilation syndrome. Usually triggered by acute anxiety, this syndrome may produce transient paresthesia in the hands, feet, and perioral area, accompanied by agitation, vertigo, syncope, pallor, muscle twitching and weakness, carpopedal spasm, and cardiac arrhythmias.

♦ Hypocalcemia. Asymmetrical paresthesia usually occurs in the fingers, toes, and circumoral area early in this disorder. Other signs and symptoms are muscle weakness, twitching, or cramps; palpitations; hyperactive DTRs; carpopedal spasm; and positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs.

♦ Migraine headache. Paresthesia in the hands, face, and perioral area may herald an impending migraine headache. Other prodromal symptoms include scotomas, hemiparesis, confusion, dizziness, and photophobia. These effects may persist during the characteristic throbbing headache and continue after it subsides.

♦ Multiple sclerosis (MS). With this disorder, demyelination of the sensory cortex or spinothalamic tract may produce paresthesia— typically one of the earliest symptoms. Like other effects of MS, paresthesia commonly waxes and wanes until the later stages, when it may become permanent. Associated findings include muscle weakness, spasticity, and hyperreflexia.

♦ Peripheral nerve trauma. Injury to any major peripheral nerve can cause paresthesia—often dysesthesia—in the area supplied by that nerve. Paresthesia begins shortly after trauma and may be permanent. Other findings are flaccid paralysis or paresis, hyporeflexia, and variable sensory loss.

♦ Peripheral neuropathy. This syndrome can cause progressive paresthesia in all extremities. The patient also commonly displays muscle weakness, which may lead to flaccid paralysis and atrophy; loss of vibration sensation; diminished or absent DTRs; neuralgia; and cutaneous changes, such as glossy, red skin and anhidrosis.

♦ Rabies. Paresthesia, coldness, and itching at the site of an animal bite herald the prodromal stage of rabies. Other prodromal signs and symptoms are fever, headache, photophobia, hyperesthesia, tachycardia, shallow respirations, and excessive salivation, lacrimation, and perspiration.

♦ Raynaud’s disease. Exposure to cold or stress makes the fingers turn pale, cold, and cyanotic; with rewarming, they become red and paresthetic. Ulceration may occur in chronic cases.

♦ Seizure disorders. Seizures originating in the parietal lobe usually cause paresthesia of the lips, fingers, and toes. The paresthesia may act as auras that precede tonic-clonic seizures.

♦ Spinal cord injury. Paresthesia may occur in partial spinal cord transection, after spinal shock resolves. It may be unilateral or bilateral,

occurring at or below the level of the lesion. Associated sensory and motor loss is variable. (See Understanding spinal cord syndromes, page 524.) Spinal cord disorders may be associated with paresthesia on head flexion (Lhermitte’s sign).

occurring at or below the level of the lesion. Associated sensory and motor loss is variable. (See Understanding spinal cord syndromes, page 524.) Spinal cord disorders may be associated with paresthesia on head flexion (Lhermitte’s sign).

♦ Spinal cord tumors. Paresthesia, paresis, pain, and sensory loss along nerve pathways served by the affected cord segment result from such tumors. Eventually, paresis may cause spastic paralysis with hyperactive DTRs (unless the tumor is in the cauda equina, which produces hyporeflexia) and, possibly, bladder and bowel incontinence.

♦ Stroke. Although contralateral paresthesia may occur with stroke, sensory loss is more common. Associated features vary with the artery affected and may include contralateral hemiplegia, decreased LOC, and homonymous hemianopsia.

♦ Systemic lupus erythematosus. This disorder may cause paresthesia, but its primary signs and symptoms include nondeforming arthritis (usually of hands, feet, and large joints), photosensitivity, and a “butterfly rash” that appears across the nose and cheeks.

♦ Tabes dorsalis. With this disorder, paresthesia —especially of the legs—is a common, but late, symptom. Other findings include ataxia, loss of proprioception and pain and temperature sensation, absent deep tendon reflexes, Charcot’s joints, Argyll Robertson pupils, incontinence, and impotence.

♦ Thoracic outlet syndrome. Paresthesia occurs suddenly in this syndrome when the affected arm is raised and abducted. The arm also becomes pale and cool with diminished pulses. Unequal blood pressure between arms may be noted.

♦ Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Paresthesia typically occurs abruptly with a TIA and is limited to one arm or another isolated part of the body. It usually lasts about 10 minutes and is accompanied by paralysis or paresis. Associated findings include decreased LOC, dizziness, unilateral vision loss, nystagmus, aphasia, dysarthria, tinnitus, facial weakness, dysphagia, and ataxic gait.

♦ Vitamin B deficiency. Chronic thiamine or vitamin B12 deficiency may cause paresthesia and weakness in the arms and legs. Burning leg pain, hypoactive DTRs, and variable sensory loss are common in thiamine deficiency; vitamin B12 deficiency also produces mental status changes and impaired vision.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Phenytoin, chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine, vinblastine, and procarbazine), D-penicillamine, isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, chloroquine, and parenteral gold therapy may produce transient paresthesia that disappears when the drug is discontinued.

♦ Radiation therapy. Long-term radiation therapy eventually may cause peripheral nerve damage, resulting in paresthesia.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because paresthesia is commonly accompanied by patchy sensory loss, teach the patient safety measures. For example, have him test bath water with a thermometer.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Although children may experience paresthesia associated with the same causes as adults, many are unable to describe this symptom. Nevertheless, hereditary polyneuropathies are usually first recognized in childhood.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

Typically dramatic and terrifying to the patient, this sign refers to an attack of dyspnea that abruptly awakens the patient. Common findings include diaphoresis, coughing, wheezing, and chest discomfort. The attack abates after the patient sits up or stands for several minutes, but may recur every 2 to 3 hours.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is a sign of left-sided heart failure. It may result from decreased respiratory drive, impaired left ventricular function, enhanced reabsorption of interstitial fluid, or increased thoracic blood volume. All of these pathophysiologic mechanisms cause dyspnea to worsen when the patient lies down.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Begin by exploring the patient’s complaint of dyspnea. Does he have dyspneic attacks only at night or at other times as well, such as after exertion or while sitting down? If so, what type of activity triggers the attack? Does he experience coughing, wheezing, fatigue, or weakness during an attack? Find out if he has a history of lower extremity edema or jugular vein distention. Ask if he sleeps with his head elevated and, if so, on how many pillows or if he sleeps in a reclining chair. Obtain a cardiopulmonary history. Does the patient or a family member have a history of a myocardial infarction,

coronary artery disease, or hypertension, or of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma? Has the patient had cardiac surgery?

coronary artery disease, or hypertension, or of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma? Has the patient had cardiac surgery?

Next perform a physical examination. Begin by taking the patient’s vital signs and forming an overall impression of his appearance. Is he noticeably cyanotic or edematous? Auscultate the lungs for crackles and wheezing and the heart for gallops and arrhythmias.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Left-sided heart failure. Dyspnea—on exertion, during sleep, and eventually even at rest—is an early sign of left-sided heart failure. This sign is characteristically accompanied by Cheyne-Stokes respirations, diaphoresis, weakness, wheezing, and a persistent, nonproductive cough or a cough that produces clear or blood-tinged sputum. As the patient’s condition worsens, he develops tachycardia, tachypnea, alternating pulse (commonly initiated by a premature beat), a ventricular gallop, crackles, and peripheral edema.

With advanced left-sided heart failure, the patient may also exhibit severe orthopnea, cyanosis, clubbing, hemoptysis, and cardiac arrhythmias as well as signs and symptoms of shock, such as hypotension, weak pulse, and cold, clammy skin.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as chest X-ray, echocardiography, exercise electrocardiography, and cardiac blood pool imaging. If the hospitalized patient experiences paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, assist him to a sitting position or help him walk around the room. If necessary, provide supplemental oxygen. Try to calm him because anxiety can exacerbate dyspnea.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

In a child, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea usually stems from a congenital heart defect that precipitates heart failure. Help relieve the child’s dyspnea by elevating his head and calming him.

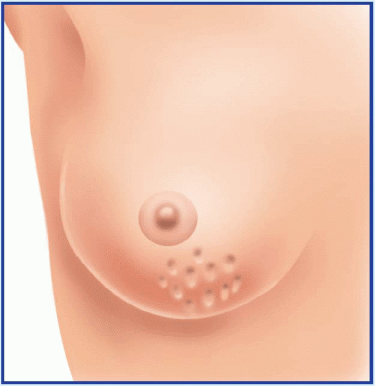

Peau d’orange

Usually a late sign of breast cancer, peau d’orange (orange peel skin) is the edematous thickening and pitting of breast skin. This slowly developing sign can also occur with breast or axillary lymph node infection, erysipelas, or Graves’ disease. Its striking orange peel appearance stems from lymphatic edema around deepened hair follicles. (See Recognizing peau d’orange.)

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient when she first detected peau d’orange. Has she noticed any lumps, pain, or other breast changes? Does she have related signs and symptoms, such as malaise, achiness, and weight loss? Is she lactating, or has she recently weaned her infant? Has she had previous axillary surgery that might have impaired lymphatic drainage of a breast?

In a well-lit examining room, observe the patient’s breasts. Estimate the extent of the peau d’orange and check for erythema. Assess the nipples for discharge, deviation, retraction, dimpling, and cracking. Gently palpate the area of peau d’orange, noting warmth or induration. Palpate the entire breast, noting any fixed or mobile lumps, and the axillary lymph nodes, noting enlargement. Take the patient’s temperature.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Breast abscess. Usually affecting lactating women with milk stasis, this infectious disorder causes peau d’orange, malaise, breast tenderness and erythema, and a sudden fever that may be accompanied by shaking chills. A cracked nipple may produce a purulent discharge, and an indurated or palpable soft mass may be present.

♦ Breast cancer. Advanced breast cancer is the most likely cause of peau d’orange, which usually begins in the dependent part of the breast or the areola. Palpation typically reveals a firm, immobile mass that adheres to the skin above the area of peau d’orange. Inspection of the breasts may reveal changes in contour, size, or symmetry. Inspection of the nipples may reveal deviation, erosion, retraction, and a thin and watery, bloody, or purulent discharge. The patient may report a burning and itching sensation in the nipples as well as a sensation of warmth or heat in the breast. Breast pain may occur, but it isn’t a reliable indicator of cancer.

♦ Erysipelas. This streptococcal infection causes a well-demarcated erythematous elevated area, typically with a peau d’orange texture. Pain, warmth, and generalized signs and symptoms, such as fever and fatigue, also occur.

♦ Graves’ disease. Patients with this thyroid disorder may exhibit raised, thickened, hyperpigmented, peau d’orange-like areas that tend to coalesce. Other common signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism include weight loss, palpitations, anxiety, heat intolerance, tremor, and amenorrhea.

♦ Tuberculosis of the axillary lymph nodes. Peau d’orange occasionally occurs as one or more axillary lymph nodes enlarge.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because peau d’orange usually signals advanced breast cancer, provide emotional support for the patient. Encourage her to express her fears and concerns. Clearly explain expected diagnostic tests, such as mammography, computed tomography scan, ultrasound, and breast biopsy.

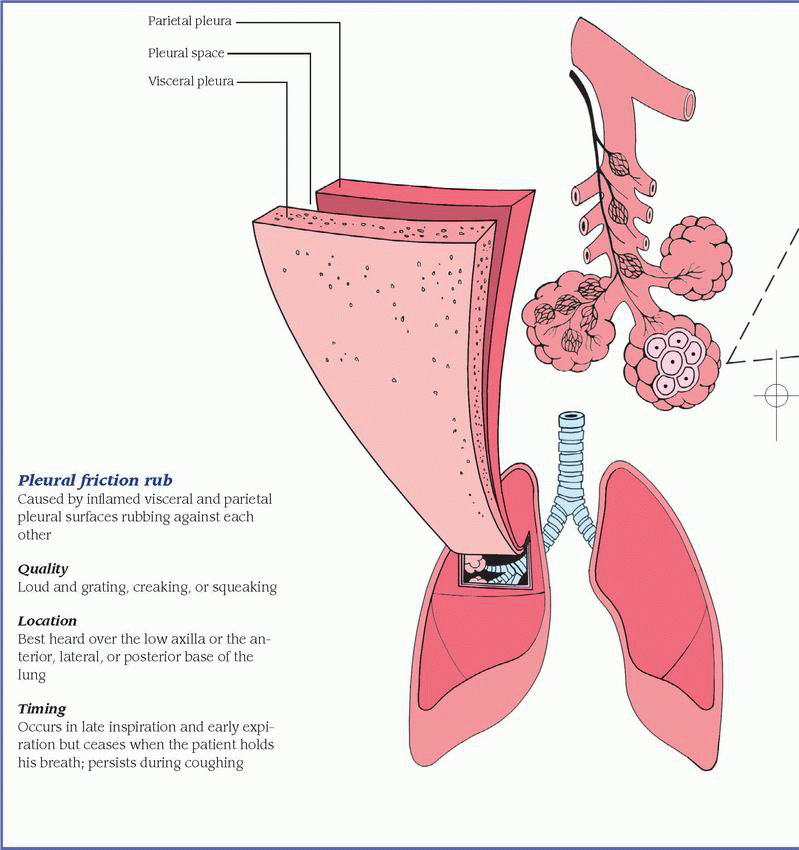

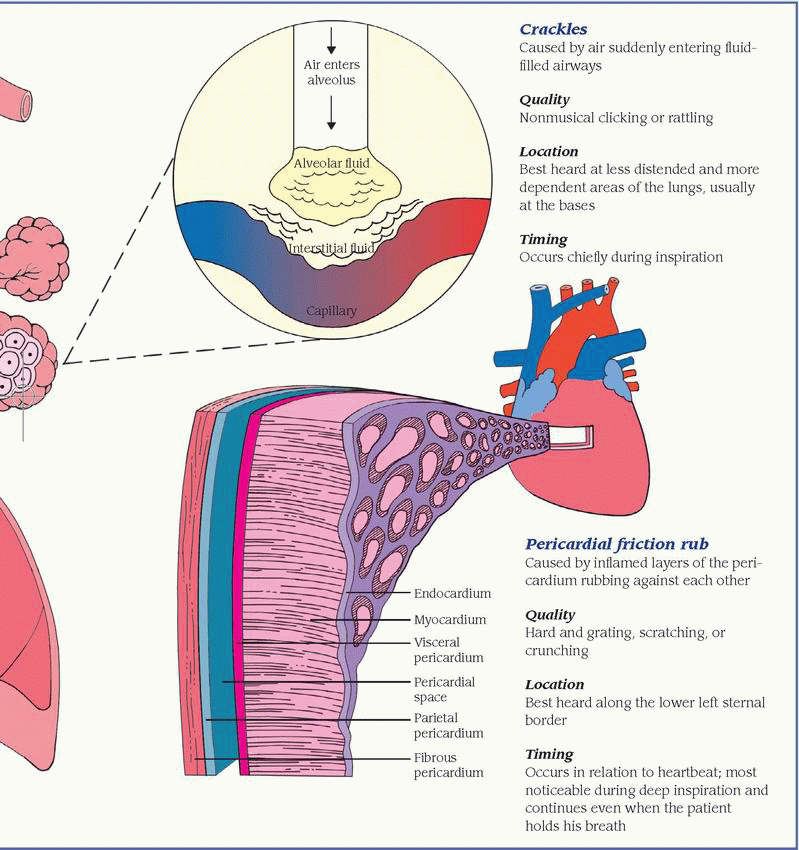

Pericardial friction rub

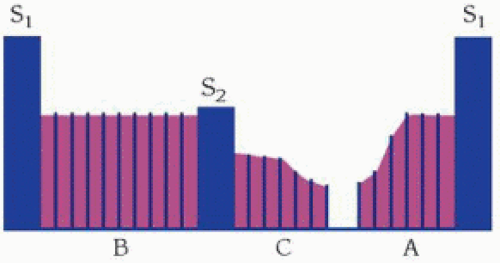

Commonly transient, a pericardial friction rub is a scratching, grating, or crunching sound that occurs when two inflamed layers of the pericardium slide over one another. Ranging from faint to loud, this abnormal sound is best heard along the lower left sternal border during deep inspiration. (See Comparing auscultation findings, pages 532 and 533.) It indicates pericarditis, which can result from acute infection, a cardiac or renal disorder, postpericardiotomy syndrome, or the use of certain drugs. Occasionally, a pericardial friction rub can resemble a murmur (see Pericardial friction rub or murmur?) or a pleural friction rub. However, the classic pericardial friction rub has three components. (See Understanding pericardial friction rubs, page 534.)

Is the sound you hear a pericardial friction rub or a murmur? Here’s how to tell. The classic pericardial friction rub has three sound components, which are related to the phases of the cardiac cycle. In some patients, however, the rub’s presystolic and early diastolic sounds may be inaudible, causing the rub to resemble the murmur of mitral insufficiency or aortic stenosis and insufficiency.

If you don’t detect the classic threecomponent sound, you can distinguish a pericardial friction rub from a murmur by auscultating again and asking yourself these questions:

How deep is the sound?

A pericardial friction rub usually sounds superficial; a murmur sounds deeper in the chest.

Does the sound radiate?

A pericardial friction rub usually doesn’t radiate; a murmur may radiate widely.

Does the sound vary with inspiration or changes in patient position?

A pericardial friction rub is usually loudest during inspiration and is best heard when the patient leans forward. A murmur varies in timing and duration with both factors.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Obtain a complete medical history, noting especially cardiac dysfunction. Has the patient recently had a myocardial infarction or cardiac surgery? Has he ever had pericarditis or rheumatic disorder, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus? Does he have chronic renal failure or an infection? If the patient complains of chest pain, ask him to describe its character and location. What relieves the pain? What worsens it?

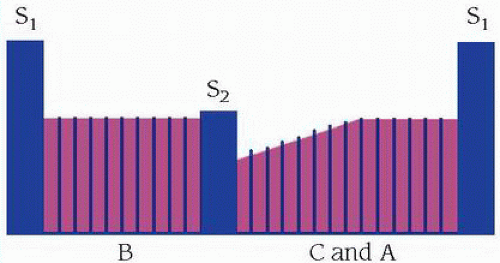

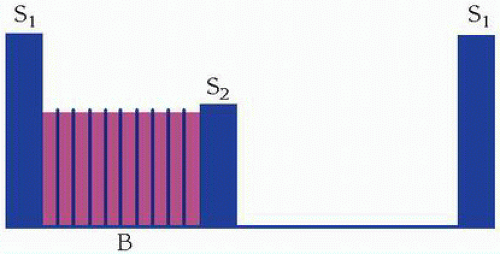

The complete, or classic, pericardial friction rub is triphasic. Its three sound components are linked to phases of the cardiac cycle. The presystolic component (A) reflects atrial systole and precedes the first heart sound (S1). The systolic component (B)—usually the loudest—reflects ventricular systole and occurs between the S1 and second heart sound (S2). The early diastolic component (C) reflects ventricular diastole and follows the S2.

Sometimes, the early diastolic component merges with the presystolic component, producing a diphasic to-and-fro sound on auscultation. In other patients, auscultation may detect only one component—a monophasic rub, typically during ventricular systole.

Take the patient’s vital signs, noting especially hypotension, tachycardia, irregular pulse, tachypnea, and fever. Inspect for jugular vein distention, edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly. Auscultate the lungs for crackles.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Pericarditis. A pericardial friction rub is the hallmark of acute pericarditis. This disorder also causes sharp precordial or retrosternal pain that usually radiates to the left shoulder, neck, and back. The pain worsens when the patient breathes deeply, coughs, or lies flat and, possibly, when he swallows. It abates when he sits up and leans forward. The patient may also develop fever, dyspnea, tachycardia, and arrhythmias.

With chronic constrictive pericarditis, a pericardial friction rub develops gradually and is accompanied by signs of decreased cardiac filling and output, such as peripheral edema, ascites, jugular vein distention on inspiration (Kussmaul’s sign), and hepatomegaly. Dyspnea, orthopnea, paradoxical pulse, and chest pain may also occur.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Procainamide and chemotherapeutic drugs can cause pericarditis.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Continue to monitor the patient’s cardiovascular status. If the pericardial friction rub disappears, be alert for signs of cardiac tamponade: pallor; cool, clammy skin; hypotension; tachycardia; tachypnea; paradoxical pulse; and increased jugular vein distention. If these signs occur, prepare the patient for pericardiocentesis to prevent cardiovascular collapse.

Ensure that the patient gets adequate rest. Give an anti-inflammatory, antiarrhythmic, diuretic, or antimicrobial to treat the underlying cause. If necessary, prepare him for a pericardiectomy to promote adequate cardiac filling and contraction.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Bacterial pericarditis may develop during the first two decades of life, usually before age 6. Although a pericardial friction rub may occur, other signs and symptoms—such as fever, tachycardia, dyspnea, chest pain, jugular vein distention, and hepatomegaly—more reliably indicate this life-threatening disorder. A pericardial friction rub may also occur after surgery to correct congenital cardiac anomalies. However, it usually vanishes without development of pericarditis.

Peristaltic waves, visible

With intestinal obstruction, peristalsis temporarily increases in strength and frequency as the intestine contracts to force its contents past the obstruction. As a result, visible peristaltic waves may roll across the abdomen. Typically, these waves appear suddenly and vanish quickly, because increased peristalsis overcomes the obstruction or the GI tract becomes atonic. Peristaltic waves are best detected by stooping at the patient’s side and inspecting his abdominal contour while he’s in a supine position.

Visible peristaltic waves may also reflect normal stomach and intestinal contractions in thin patients or in malnourished patients with abdominal muscle atrophy.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After observing peristaltic waves, collect pertinent history data. For example, ask about a history of pyloric ulcer, stomach cancer, or chronic gastritis, which can lead to pyloric obstruction. Ask about conditions leading to intestinal obstruction, such as intestinal tumors or polyps, gallstones, chronic constipation, and a hernia. Has the patient had recent abdominal surgery? Be sure to obtain a drug history.

Determine if the patient has related symptoms. Spasmodic abdominal pain, for example, accompanies small-bowel obstruction, whereas colicky pain accompanies pyloric obstruction. Is the patient experiencing nausea and vomiting? If he has vomited, ask about the consistency, amount, and color of the vomitus. Lumpy vomitus may contain undigested food particles; green or brown vomitus may contain bile or fecal matter.

Next, with the patient in a supine position, inspect the abdomen for distention, surgical scars and adhesions, or visible loops of bowel. Auscultate for bowel sounds, noting high-pitched, tinkling sounds. Then jar the patient’s bed (or roll the patient from side to side) and auscultate for a succussion splash—a splashing sound in the stomach from retained secretions due to pyloric obstruction. Palpate the abdomen for rigidity and tenderness, and percuss for tympany. Check the skin and mucous membranes for dryness and poor skin turgor, indicating dehydration. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting especially tachycardia and hypotension, which indicate hypovolemia.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Large-bowel obstruction. Visible peristaltic waves in the upper abdomen are an early sign of this obstruction. Obstipation, however, may be the earliest finding. Other characteristic signs and symptoms develop more slowly than in small-bowel obstruction. These include nausea, colicky abdominal pain (milder than in smallbowel obstruction), gradual and eventually marked abdominal distention, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

♦ Pyloric obstruction. Peristaltic waves may be detected in a swollen epigastrium or in the left upper quadrant, usually beginning near the left rib margin and rolling from left to right. Related findings include vague epigastric discomfort or colicky pain after eating, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Auscultation reveals a loud succussion splash.

♦ Small-bowel obstruction. Early signs of mechanical obstruction of the small bowel include peristaltic waves rolling across the upper abdomen and intermittent, cramping periumbilical pain. Associated signs and symptoms include nausea, vomiting of bilious or, later, fecal material, and constipation; in partial obstruction, diarrhea may occur. Hyperactive bowel sounds and slight abdominal distention also occur early.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because visible peristaltic waves are an early sign of intestinal obstruction, monitor the patient’s status and prepare him for diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Withhold food and fluids, and explain the purpose and procedure of abdominal X-rays and barium studies, which can confirm obstruction.

If tests confirm obstruction, nasogastric suctioning may be performed to decompress the stomach and small bowel. Provide frequent oral hygiene, and watch for a thick, swollen tongue and dry mucous membranes, indicating dehydration. Frequently monitor vital signs and intake and output.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

In infants, visible peristaltic waves may indicate pyloric stenosis. In small children, peristaltic waves may be visible normally because of the protuberant abdomen, or visible waves may indicate bowel obstruction stemming from congenital anomalies, volvulus, or the swallowing of a foreign body.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

PATIENT COUNSELING

Advise patients suffering from chronic constipation and those taking an antidepressant or antipsychotic to increase their fluid intake and eat foods high in fiber, such as cereals, fruits, and vegetables. If no improvement occurs, administer a stool softener to prevent further complications such as bowel obstruction.

Photophobia

A common symptom, photophobia is an abnormal sensitivity to light. In many patients, photophobia simply indicates increased eye sensitivity without any underlying pathology. For example, it can stem from excessive wearing of contact lenses or use of poorly fitted lenses. However, in others, this symptom can result from a systemic disorder, an ocular disorder or trauma, or the use of certain drugs. (See Photophobia: Causes and associated findings.)

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If your patient reports photophobia, find out when it began and how severe it is. Did it follow eye trauma, a chemical splash, or exposure to the rays of a sun lamp? If photophobia results from trauma, avoid manipulating the eyes. Ask the patient about eye pain and have him describe its location, duration, and intensity. Does he have a sensation of a foreign body in his eye? Does he have any other signs and symptoms, such as increased tearing and vision changes?

Next, take the patient’s vital signs and assess neurologic status. Assess visual activity, unless the cause is a chemical burn. Follow this with a careful eye examination, inspecting the eyes’ external structures for abnormalities. Examine the conjunctiva and sclera, noting their color. Characterize the amount and consistency of any discharge. Check pupillary reaction to light. Evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze, and test visual acuity in both eyes.

During your assessment, keep in mind that although photophobia can accompany lifethreatening meningitis, it isn’t a cardinal sign of meningeal irritation.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Burns. With a chemical burn, photophobia and eye pain may be accompanied by erythema and blistering on the face and lids, miosis, diffuse conjunctival injection, and corneal changes. The patient experiences blurred vision and may be unable to keep his eyes open. With an ultraviolet radiation burn, photophobia occurs with moderate to severe eye pain. These symptoms develop about 12 hours after exposure to the rays of a welding arc or sun lamp.

♦ Conjunctivitis. When conjunctivitis affects the cornea, it causes photophobia. Other common findings include conjunctival injection, increased tearing, a foreign-body sensation, a feeling of fullness around the eyes, and eye pain, burning, and itching. Allergic conjunctivitis is distinguished by a stringy eye discharge and milky red injection. Bacterial conjunctivitis tends to cause a copious, mucopurulent, flaky eye discharge that may make the eyelids stick together, as well as brilliant red conjunctiva. Fungal conjunctivitis produces a thick, purulent discharge, extreme redness, and crusting, sticky eyelids. Viral conjunctivitis causes copious tearing with little discharge as well as enlargement of the preauricular lymph nodes.