KEY TERMS

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Nongovernmental organization (NGO)

Governments ultimately have the responsibility of making the organized community efforts necessary to protect the health of the population, although many other organizations and community groups are also important participants. Government’s role is determined by law; that is, government’s public health activities must be authorized by legislation at the federal, state, or local levels. The public health law is further defined by decisions of the courts at the various levels of government. The broad decisions of the legislative and judicial branches of government are worked out in detail by the executive branch, usually the agencies which issue regulations and carry out public health programs. The ultimate authority that allows the laws to be written is the constitution or charter, whether federal, state, or local. Thus the body of public health law is massive, consisting of all the written statements relating to health by any of the three branches of government at the federal, state, and local levels.

Many nongovernmental organizations (NGO) play an important role in public health, especially through educational programs and lobbying. In recent years, stimulated in part by the Institute of Medicine’s The Future of Public Health,1 there has been increasing emphasis on community involvement in public health planning and in generating support for and participation in public health activities. This process expands the concept of the public health system to include, for example, hospitals, businesses, and charitable and religious organizations.

Federal Versus State Authority

The U.S. Constitution does not mention health. Because the Tenth Amendment states that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution … are reserved to the States respectively,” public health has been a responsibility primarily of the states. Most state constitutions provide for the protection of public health, and the original states already had laws concerning health before the Constitution took effect.2

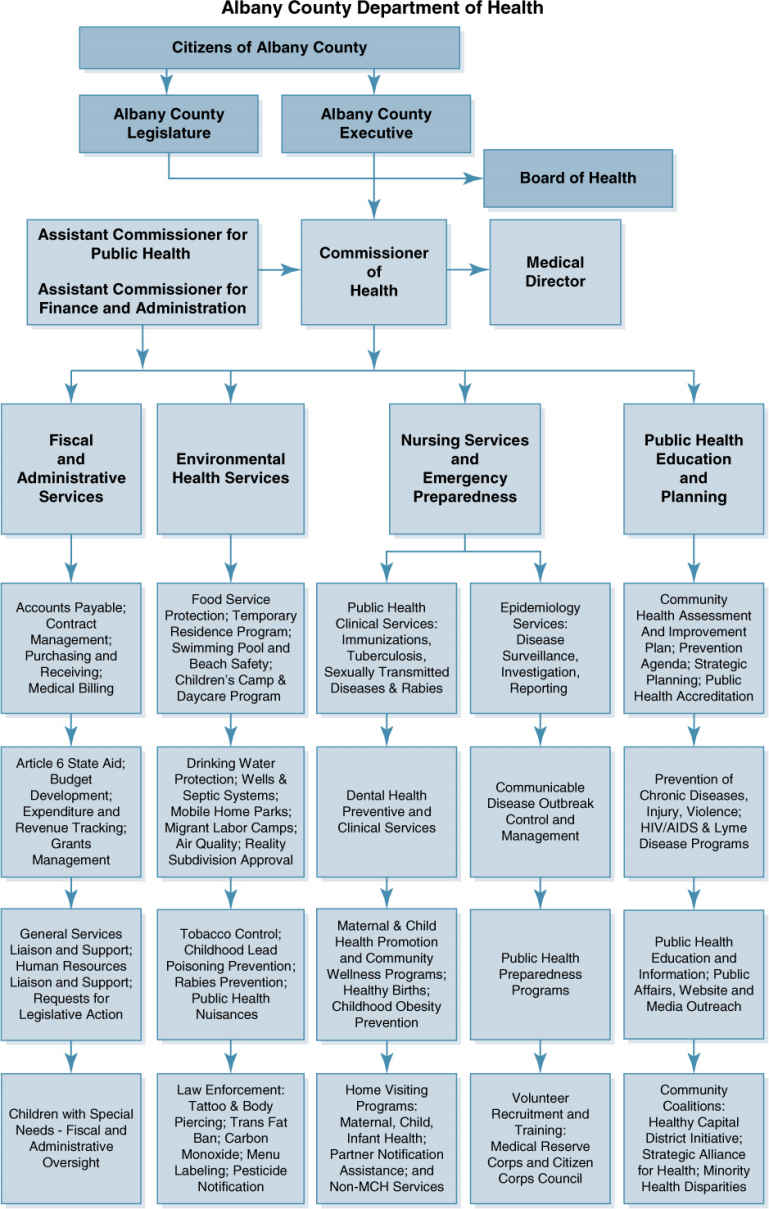

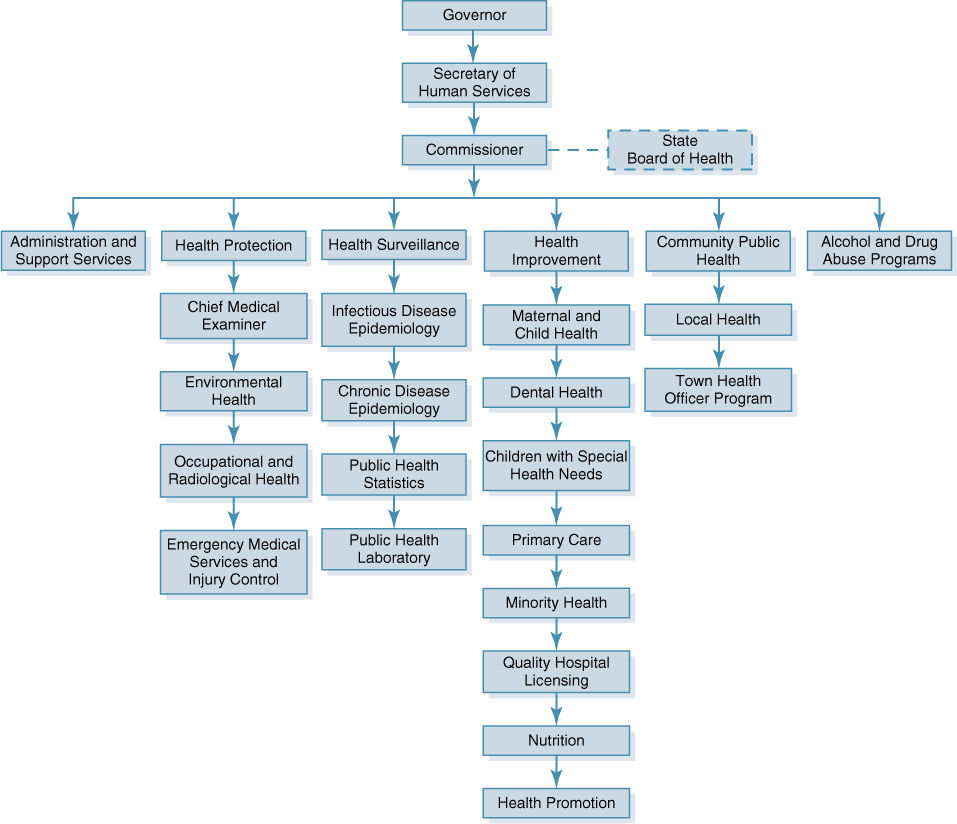

All states have laws such as mandates to collect data about the population, to immunize children before they enter school, to regulate the environment for purposes of sanitation, and to regulate safety. To a varying extent, responsibility for some public health activities may be delegated by the state to local governments. (FIGURE 3-1), an organization chart of a small state health department, shows public health activities typically provided for in state law.

The Constitution, in the Preamble, includes among the fundamental purposes of government, “to promote the general welfare.” It gives the federal government authority to regulate interstate commerce and to “collect taxes … to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and the general welfare.” These powers are the basis for the federal role in public health.

The interstate commerce provision, for example, justifies the activities of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which oversees extensive federal regulation of foods, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics, most of which are distributed across state lines. It is obviously more efficient and economical for the industries that produce these products to be bound by uniform national rules rather than having to comply with 50 different sets of state regulations.

The power to tax and spend is a way for the federal government to achieve goals that it may lack the authority to achieve directly. It can provide funds to the states subject to certain requirements. For example, in 1967 the federal government mandated that, as a precondition for receiving highway construction funds, states must pass laws requiring motorcyclists to wear helmets. The effectiveness of the mandate was demonstrated by the fact that, by 1975, 47 states had passed such laws, with the result that motorcyclist deaths declined by 30 percent in these states.3 Another example of federal influence over state health programs is the Medicaid program of providing health care for the poor. The federal government provides 50 to 80 percent of the funding for Medicaid. States and counties administer the Medicaid program, providing the remaining funds, and must follow the guidelines established by Congress.2

Since World War II, the federal government has used these powers to steadily widen its role in public health, among other matters. That trend began to reverse in the 1980s. In a political climate hostile to government, especially the federal government, there was a strong movement in Congress and the Supreme Court to cut government regulation and return more powers to the states. In an early example of the reversal, in 1976 Congress removed the financial penalty for lack of motorcycle helmet laws. By 1980, 27 states had repealed their helmet laws, and motorcycle deaths rose in those states by 38 percent.3 The Medicaid program, which has grown enormously expensive since it was established in 1965, has also been a target of Congress, which for some time threatened, without success, to hand it over to the states entirely.

FIGURE 3-1 Organization Chart of a State Health Department

In the 1990s, the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice William Rehnquist began a trend known as the new federalism, which limited Congress’s powers and returned authority to the states. For example, in 1995, the Court struck down a law making gun possession within a school zone a federal offense, rejecting the argument that gun possession was a matter of interstate commerce.4 In 2001, it decided that the Americans with Disabilities Act could not be enforced against a state, ruling that a woman who was fired from her state job because she had breast cancer could not sue the state of Alabama.5 However, the new federalism lost much of its momentum after 9/11 when, as New York Times reporter Linda Greenhouse noted, “suddenly the federal government looked useful, even necessary.” In 2003, Rehnquist “gave up and moved on,” writing the majority ruling that state governments could be sued for failing to give their employees the benefits required by the Family and Medical Leave Act.6 In 2005, the Supreme Court affirmed the priority of federal law over state law in a controversial decision ruling that patients in California could be criminally prosecuted by federal authorities for using marijuana prescribed by a physician according to California’s medical marijuana law.7

How the Law Works

Governments have broad power to act in ways that curtail the rights of individuals. These police powers of governments are basic to public health, and are the reason why public health must ultimately be government’s responsibility.8 Police powers are invoked for three reasons: to prevent a person from harming others; to defend the interests of incompetent persons such as children or the mentally retarded; and, in some cases, to protect a person from harming himself or herself.9

Laws have been used to enforce compliance in health matters for over a century. In 1905, a precedent was set for the state’s police power in the area of health when the Massachusetts legislature passed a law that required all adults to be vaccinated against smallpox. A man named Jacobson refused to comply and went to court, arguing that the law infringed on his personal liberty. The trial court found that the state was within its power to enforce the law. Jacobson appealed his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. He lost: The Supreme Court upheld the right of the state to restrict an individual’s freedom “for the common good.”4

The public health law has become more complex over the years, but it follows the same pattern. At any level of government, a legislature, perceiving a need, passes a statute. The statute may be challenged in court and the decision of the court may be appealed to higher courts. Generally, on issues of constitutionality, a state court may overturn a local law or court decision, and a federal court may overturn a state law or court decision.

Since public health increasingly involves complex technical issues, legislatures at the several levels of government generally set up administrative agencies to perform public health functions. The legislature, recognizing that it lacks the necessary expertise, authorizes these agencies to set rules that define in detail how to accomplish the purpose of the legislation. The courts may then be called on to interpret the authority of the agencies under the laws and to determine whether certain rules or decisions of an agency are within its legal authority.

As an example of the interplay of legislation, agency rule making, and the role of the courts, consider the Occupational Safety and Health Act, passed by Congress in 1970. The legislation stated that “personal injuries and illnesses arising out of work situations impose a substantial burden upon … interstate commerce,” and thus used the federal government’s authority over interstate commerce to pass a public health statute.10(p.180) The law established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) within the Department of Labor. OSHA was authorized, among other things, to set standards regulating employees’ exposure to hazardous substances. Representatives of industry challenged the constitutional authority of Congress to pass the law but were unsuccessful.

Industries that feel economically harmed by OSHA’s standard setting have used other routes to weaken the agency’s power. One of the substances that OSHA decided to regulate was benzene, which caused a variety of toxic effects among workers in the rubber and petrochemical industries. In 1971, OSHA set a standard limiting benzene exposure to 10 parts per million (ppm) in air, averaged over an 8-hour period. Epidemiologic evidence indicated, however, that exposure to lower concentrations of benzene over time might increase the risk of leukemia, and there was laboratory evidence to support those studies. Therefore, in 1978, OSHA lowered the standard to 1 ppm over an 8-hour period. Representatives of the affected industries appealed the new regulations in court, claiming that evidence that benzene causes leukemia was not sufficiently strong, and that complying with the new standard would be too expensive. The court, in a ruling upheld later by the Supreme Court, agreed that OSHA did not have sufficient evidence to support the need for the new standard and thus had exceeded its authority in issuing the regulation.10 The standard remained at 10 ppm until 1987, when evidence for the carcinogenicity of benzene was deemed convincing enough to justify the lower value.11

The courts did not rule on whether the cost of complying with a standard should be considered in the process of setting it. The act had specified that standards should ensure the health of workers “to the extent feasible.”10(p.180) Industry argued that OSHA should have done a cost–benefit analysis before issuing the regulation. This issue was decided in another case, in which the courts determined that a formal cost–benefit analysis was not required in the law.10 Usually, the expected cost of implementing regulations is considered together with the potential benefits when decisions are made. However, there is plenty of room for controversy over the relative magnitudes of the costs and benefits.

Since regulatory activities of federal and state governments are so fundamental to public health, they will often be discussed throughout this text.

How Public Health Is Organized and Paid for in the United States

Local Public Health Agencies

The organization of public health at the local level varies from state to state and even within states. The most common local agency is the county health department. A large city may have its own municipal health department, and rural areas may be served by multicounty health departments. Some local areas have no public health department, leaving their residents to do without some services and to depend on state government for others.

Local health departments have the day-to-day responsibility for public health matters in their jurisdiction. These include collecting health statistics; conducting communicable disease control programs; providing screening and immunizations; providing health education services and chronic disease control programs; conducting sanitation, sanitary engineering, and inspection programs; running school health programs; and delivering maternal and child health services and public health nursing services. Mental health may or may not be the responsibility of a separate agency.

In many states, laws assign local public health agencies the responsibility for providing medical care to the poor. While this task may be considered part of the assurance function defined in The Future of Public Health,1 the Institute of Medicine found that this role tends to consume excessive resources and distract local health departments from performing their assessment and policy development functions. The provision of medical services by public health clinics has often been a source of friction with the medical establishment. Functions of a typical county health department are shown in the organizational chart (FIGURE 3-2).

The source of funds for local health department activities varies widely among states. Some states provide the bulk of funding for local health departments while others provide very little. The federal government may fund some local health department activities directly, or federal funds may be passed on from the states. A portion of the local health budget usually comes from local property and sales taxes, and from fees that the department charges for some services. The extent to which local health departments are responsive to mandates from the state and federal government is likely to depend on how much of the local agency’s budget is provided by these sources. When the bulk of a local health department’s budget is determined by a city council or county legislature, the local agency’s capacity to perform core functions may depend on its ability to educate the legislative body about public health and its importance.

State Health Departments

The states have the primary constitutional responsibility and authority for the protection of the health, safety, and general welfare of the population, and much of this responsibility falls on state health departments. The scope of this responsibility varies: Some states have separate agencies for social services, aging, mental health, the environment, and so on. This may cause problems, for example, when the environmental agency makes decisions that impact the population’s health without consulting the health agency, or—in one example described by the Institute of Medicine—when the Indian Health Service, the state health agency, and the state mental health agency argued about which was responsible for adult and aging services.1 Some state health departments are strongly centralized, while others delegate much of their authority to the local health departments. State health departments depend heavily on federal money for many programs, and their authority is thus limited by the strings attached to the federal funds.

State health departments define to varying degrees the activities of the local health departments. The state health department may set policies to be followed by the local agencies, and they generally provide significant funding, both from state sources and as channels for federal funds. The state health department coordinates activities of the local agencies and collects and analyzes the data provided by the local agencies. Laboratory services are often provided by state health departments.

State health departments are usually charged with licensing and certification of medical personnel, facilities, and services, with the purpose of maintaining standards of competence and quality of care. An organization chart of a typical state health department is shown in Figure 3-1.

People who lack private health insurance are generally the concern of state health departments, although many states pass this responsibility on to localities. Some of these people are covered by Medicaid, the joint federal–state program for the poor. States have significant—though not total—flexibility in how to administer the Medicaid program, determining eligibility rules for coverage as well as setting payment amounts for the doctors, hospitals, and other providers of medical care. Most states also provide some kind of funding to hospitals to reimburse them for treating uninsured patients who arrive in the emergency room and must be treated.