9 Postoperative care and complications

Introduction

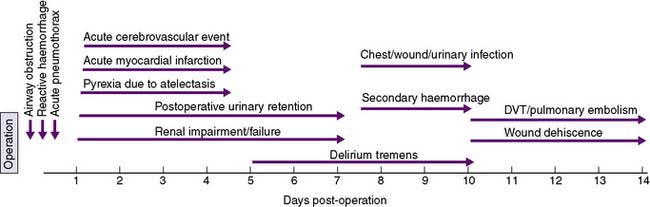

A timeline showing typical times for the development of postoperative complications is given in Figure 9.1.

Immediate postoperative care

Monitoring of airway, breathing and circulation is the main priority in the immediate postoperative period (EBM 9.1). The nature of the surgery and the patient’s premorbid medical condition will determine the intensity of postoperative monitoring required; however, the patient’s colour, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness will be routinely observed. The nature and volume of drainage into collecting bags or wound dressings, and urinary output are also monitored, if appropriate. Continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring is undertaken and oxygenation is assessed by the use of a pulse oximeter. Monitoring of central venous pressure (CVP) may be indicated if the patient is hypotensive, has borderline cardiac or respiratory function, or requires large amounts of intravenous fluids.

Airway obstruction

The main causes of airway obstruction are as follows:

• Obstruction by the tongue may occur with a depressed level of consciousness. Loss of muscle tone causes the tongue to fall back against the posterior pharyngeal wall, and may be aggravated by masseter spasm during emergence from anaesthesia. Bleeding into the tongue or soft tissues of the mouth or pharynx may be a complicating factor after operations involving these areas.

• Obstruction by foreign bodies, such as dentures, crowns and loose teeth. Dentures must be removed before operation and precautions taken to guard against displacement of crowns or teeth.

• Laryngeal spasm can occur at light levels of unconsciousness and is aggravated by stimulation.

• Laryngeal oedema may occur in small children after traumatic attempts at intubation, or when there is infection (epiglottitis).

• Tracheal compression may follow operations in the neck, and compression by haemorrhage is a particular anxiety after thyroidectomy.

• Bronchospasm or bronchial obstruction may follow inhalation of a foreign body or the aspiration of irritant material, such as gastric contents. It may also occur as an idiosyncratic reaction to drugs and as a complication of asthma.

Attention is directed at defining and rectifying the cause of airway obstruction as a matter of extreme urgency. Airway maintenance techniques include the chin-lift or jaw-thrust manoeuvres, which lift the mandible anteriorly and displace the tongue forward (see Chapter 8). The pharynx is then sucked out, an oropharyngeal airway is inserted to maintain the airway, and supplemental oxygen is administered. If cyanosis does not improve or if stridor persists, reintubation may be necessary.

Surgical ward care

Nutrition

Nutrition in postoperative patients is frequently poorly managed. A few days of starvation may cause little harm, but enteral or parenteral nutrition is essential if starvation is prolonged. Enteral nutrition is preferred, as it is associated with fewer complications and is believed to augment gut barrier function. If a prolonged period of starvation is anticipated in the postoperative period, a feeding jejunostomy tube can be inserted at the time of abdominal surgery. Alternatively, a fine-bore nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tube can be passed (see Chapter 8). If the enteral route cannot be used, total parenteral nutrition can be prescribed. Dietary intake should be monitored in all patients in the postoperative period, and oral high-calorie supplements given if appropriate.