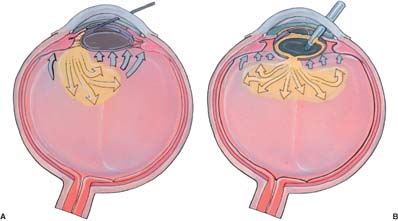

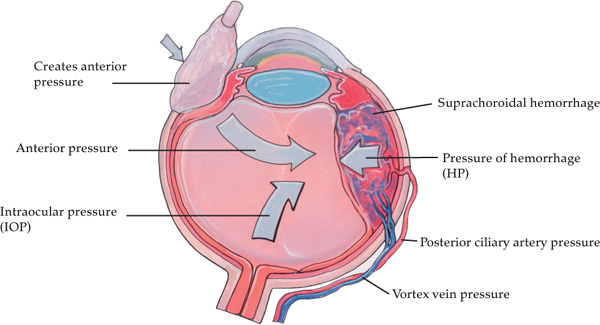

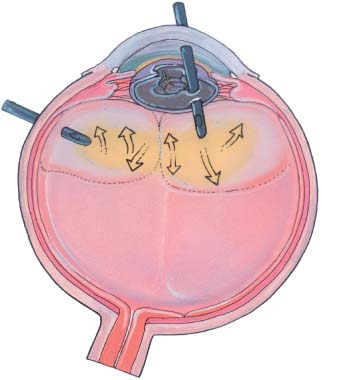

Chapter 8 One of the most disconcerting problems faced by the anterior segment surgeon with an open eye is progressive positive pressure. With this sudden rise in intraocular pressure, the cataract surgeon finds there is no room in which to work. The risk to the endothelium rises (as does the surgeon’s heart rate and blood pressure) and the surgeon shudders to think of inadvertently tearing a convex posterior capsule. Raising the infusion bottle and instilling more viscoelastic only cause more iris prolapse. The situation gets worse by the minute! The more the surgeon does to ameliorate the situation, the worse it gets. This horrible cascade of events could lead to the worst outcome—an expulsive hemorrhage. How should the cataract surgeon evaluate and deal with this awful scenario? It is necessary to understand the various risk factors leading to positive pressure in a given patient. This awareness should lead the surgeon to consider preventive measures. The surgeon must recognize positive pressure at the earliest moment to begin the evaluation process that will lead to the best therapeutic decisions. This is one of those intraoperative situations where old aphorisms ring true: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and a stitch in time saves nine—literally! Positive pressure during cataract surgery can be classified into three general groups: (1) mechanical or external forces applied to the eye, (2) intraocular fluid deviation or misdirection into the posterior segment, and (3) acute intraoperative suprachoroidal effusion and hemorrhage. Once an accurate categorical assessment has been made, the surgeon can perform the appropriate intervention. Certain patients are more likely to demonstrate positive pressure because of their inherent periocular anatomy. Those with small palpebral fissures and tight orbits require special attention. The more forcefully the speculum is opened, the more eye pressure is created by forcing more orbital fat and tissue posteriorly. The surgeon must find the optimum speculum opening, perhaps accepting a less than ideal aperture. There is greater accessibility afforded by a temporal approach to the eye. A lateral canthotomy can be performed, although this is of marginal benefit. The speculum itself can be a source of positive pressure. Specula with larger solid blades to sequester the lid margin can occupy enough space to exert external pressure on the eye. The lighter KratzBarraquer wire speculum may help in this regard. The surgical assistant can help by elevating the speculum and the offending lid (with a muscle hook or irrigating cannula) to alleviate this external force. The independently clamped Jaffe specula may also prove useful. The phaco tip or handpiece may inadvertently push on the speculum, transmitting this pressure to the eye (especially with closed bladed specula). If using a bridle suture, overtightening may be a cause. Therefore, loosen the bridle suture. Better yet, don’t use one! In all of these lid/speculum-related situations, it is helpful to use the sterile drape or Steri-Strips to “tape open” the lids. This exerts no pressure on the globe and the speculum becomes merely an adjunct in opening the lids. The regional anesthetic block given before cataract surgery can lead to positive posterior pressure. The fear of depositing too much fluid behind the eye may be one reason many surgeons still prefer the retrobulbar to the peribulbar block. An effective block can be achieved with as little as 3.0 mL given in a retrobulbar fashion; however, this type of block usually requires an additional seventh cranial nerve or lid block. The peribulbar is effective with as little as 5.0 mL of anesthetic, but may require much more volume in larger orbits to get adequate akinesia and anesthesia. Both methods are good, although I prefer the peribulbar.1 Both can “over-fill” the orbit leading to positive pressure. The best way to prevent overfill is to palpate the globe and orbit while administering the anesthetic. I have seen this problem occur infrequently once the surgeon or anesthetist develops a “feel” for the proper orbital volume. There is no single volume that is correct for every patient’s eye. The use of hyaluronidase (Wydase) in the anesthetic mixture is exceedingly effective in promoting the distribution of the anesthetic throughout the periocular tissues. When clinical trials were performed without this protein enzyme in the peribulbar block, there was a much greater incidence of positive orbital pressure. It could be concluded that the anesthetic acted more like a “space-occupying lesion” rather than absorbing into the interstitial space of the orbital tissues. The surgeon should recognize excessive orbital volume when the lids are too tight to open adequately and chemosis is present. This can occur even when devices to soften the eye, such as the Honan balloon, are used. Once recognized, the prudent surgeon will place the Honan balloon back on the eye and simply wait. After an additional 30 minutes, the surgery can be completed with much greater ease than if the surgeon had pushed ahead with a tight orbit. Retrobulbar hemorrhage is another complication of injection anesthesia leading to positive pressure. Any type of block and any type of needle can cause a periocular hemorrhage. Most of the time it can be controlled with external pressure applied for 15 to 30 minutes, and surgery can be completed. However, if the hemorrhage is severe, causing extremely elevated intraocular pressure, surgery should be postponed and the patient’s pressure treated aggressively. The surgeon must constantly consider the intraocular fluid dynamics at work during phacoemulsification. Excessive outflow and/or restricted inflow are common causes of pseudo–positive pressure. If the phaco incision or the paracentesis are too large, the intracameral pressure cannot be maintained and the chamber will shallow. The slightest external force on the eye will exacerbate the condition. Simply elevating the BSS infusion bottle will not solve the problem of excessive outflow. The surgeon should maintain a constant, slightly elevated intracameral pressure. If excessive outflow is causing a shallow, dangerous anterior chamber, stop and place a suture or two to create a more watertight chamber. Remember that infusion bottle height is relative to patient eye height. Temporal incisions often require elevation of the patient to make room for the surgeon’s legs. If the patient’s eye is higher, the bottle needs to be proportionately higher. In varying circumstances, this syndrome has gone by various names: aqueous misdirection, ciliary block, and malignant glaucoma (in the postoperative setting). The etiology is similar in all circumstances—the aqueous or BSS is diverted behind the zonulocapsular diaphragm into the vitreous and creates high pressure within the posterior segment. This can lead to pupillary block and angle closure as the lens and iris shift forward, exacerbating the intraocular pressure elevation. There is anterior rotation of the ciliary body, the chamber shallows, and during surgery the iris may prolapse. If the surgeon continues to infuse fluid, the eye gets harder and the surgeon gets more frustrated. The zonulocapsular diaphragm acts like a one-way valve, assisted by an intact vitreous face; BSS gets into the posterior segment and it is blocked from reentry into the anterior chamber by the “vitreous valve” (Fig. 8–1). FIGURE 8–1 Fluid misdirection. If fluid passes through (A) the zonules or (B) an opening in the posterior capsule, it can create an aqueous pocket behind the vitreous face. In turn, this may force the vitreous forward, closing the “vitreous valve.” A ciliary block is created when this fluid cannot escape from the posterior segment. There are several risk factors likely to give rise to this syndrome. Anything that disrupts the zonular apparatus—pseudoexfoliation syndrome, previous ocular trauma, a radial tear in the anterior capsule, zonulysis, and any opening in the posterior capsule—may allow fluid to pass through into the posterior segment. A small pupil and a narrow angle may hide these peripheral capsular defects, delaying the surgeon’s recognition of this syndrome. Fluid deviation can occur during any phase of the operation in which fluid is infused into the eye. The surgeon must be aware that hydrodissection, phacoemulsification, and irrigation and aspiration (I&A) can all cause fluid misdirection and positive pressure. During hydrodissection, the cannula may inadvertently not be placed under the anterior capsule. The injection forces fluid through the zonules into the vitreous. Another scenario was described by Updegraff et al2 in small pupil cases: the fluid is injected under the anterior capsule, but this leads to elevation of the capsule and lens, causing pupillary block. They believe the viscoelastic may contribute to an iridocapsular seal by causing adhesion of the iris to the capsule, preventing fluid egress. During phacoemulsification, the fluid may be forced posteriorly if a dense viscoelastic prevents good anterior fluid circulation and the bottle is quite high. This problem has been encountered when an occult radial capsular tear or small area of zonulysis occurs. An intact vitreous face closes the one-way valve that leads to elevated posterior pressure. During I&A, fluid misdirection has occurred by aggressively attempting to aspirate subincisional cortex. A small iatrogenic anterior capsular tear can allow the BSS to be infused into the vitreous. This usually forces the iris up into the incision with positive posterior pressure. Even aspirating the viscoelastic from the eye after lens placement can lead to BSS misdirection and shallowing of the anterior chamber. This can occur if the surgeon is intent on going behind the intraocular lens (IOL) to remove all traces of viscoelastic—if there is a small opening in the zonulocapsular diaphragm. At the first sign of positive pressure, the surgeon should remove the irrigating instrument from the eye and apply Q-tip pressure over the incision. Q-tip pressure entails holding a cotton-tipped applicator like a pencil and pushing down on the anterior lip of the incision (Fig. 8–2). This simultaneously closes the incision and creates anterior pressure to counteract the posterior pressure—from whatever etiology. This maneuver stabilizes the eye while the surgeon assesses the situation. He then determines which of the three main causes of positive pressure this episode is due to: external forces, fluid misdirection, or acute intraoperative suprachoroidal effusion/hemorrhage. FIGURE 8–2 To tamponade the rising “posterior pressure” behind the retina during an acute intraoperative suprachoroidal hemorrhage (AISH), the surgeon must raise the “anterior pressure,” the intraocular pressure (IOP). The posterior pressure is determined by the blood pressure in the ciliary arteries and the impedance to outflow in the vortex veins. The IOP is raised by Q-tip pressure on the globe. Once the surgeon has concluded that the etiology is fluid misdirection, several options are available. I usually just continue to apply Q-tip pressure until the eye softens. The fluid eventually reequilibrates by seeping back into the anterior chamber or by being absorbed. If an impatient surgeon chooses not to wait 5 to 15 minutes, the incision can be sutured and a Honan balloon placed over the eye for 15 to 30 minutes. This has almost always worked for me. After watchful waiting, the procedure can be completed using a “low-flow” technique. Lower the infusion bottle, use plenty of viscoelastic to maintain the anterior chamber, and avoid the area of zonulocapsular disruption. Use viscoelastic to seal off this area of disruption. Decreasing the aspiration/flow rate may also increase safety. The goal is to avoid pushing more fluid into the posterior segment. More aggressive intervention may rarely be required. An acute intraoperative suprachoroidal hemorrhage (AISH) must be ruled out as the etiology of the increased intraocular pressure. This can be done by examination of the periphery with an indirect ophthalmoscope. Alternatively, Robert Osher3 has developed a fundus lens for examination of the periphery that can be maintained sterile and utilized in just such an emergency. Once it is verified that an AISH has not occurred, the increased intraocular pressure (IOP) can be alleviated by a pars plana vitreous tap using a 21-gauge needle. The needle should be inserted 3.0 to 4.0 mm posterior to the limbus and directed toward the central anterior vitreous. Slowly withdraw 0.1 to 0.3 mL of liquid vitreous. If this is not effective, it may be necessary to use a mechanical vitrectomy instrument to perform a core vitrectomy. The vitreous behind the open zonulocapsular region must be removed or allowed to fall back from the affected area (Fig. 8–3). The one-way valve must be opened. FIGURE 8–3 To break the fluid misdirection block, the surgeon must remove the “vitreous valve.” This is accomplished by vitrectomy in the area behind the open capsule or zonulysis. Work done on pseudophakic malignant glaucoma has shown that an intact posterior capsule and/or vitreous face can prevent resolution of the problem.4 An evident opening in the posterior capsule requires a vitrectomy through this opening rather than creating a pars plana incision. The aqueous must be able to circulate freely and not remain trapped behind cortical vitreous or an intact anterior hyaloid.

POSITIVE PRESSURE

CLASSIFICATION

MECHANICAL OR EXTERNAL CAUSES

LIDS AND SPECULUM

REGIONAL ANESTHESIA

FLUID DYNAMICS

FLUID DEVIATION OR MISDIRECTION SYNDROME

ETIOLOGY

COMMON ENVIRONMENT FOR FLUID MISDIRECTION

TREATMENT OF FLUID DEVIATION

ACUTE INTRAOPERATIVE SUPRACHOROIDAL HEMORRHAGE (AISH)

ETIOLOGY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree