KEY TERMS

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

Population biology is a science in itself. Studies of animal, plant, and microorganism populations have yielded some concepts and insights that can be applied to human populations. However, application of these studies’ findings to human populations is an inexact science, and predictions are always highly controversial. Interest in the dynamics of the human population arises from concern about its continuing growth and its increasing impact on the environment.

All organisms tend to produce more offspring than would be needed to maintain a stable population. Pressures from the environment, such as availability of food and prevalence of predators, tend to limit the survival of those offspring. The difference between the birth rate and the death rate is the population’s rate of growth.

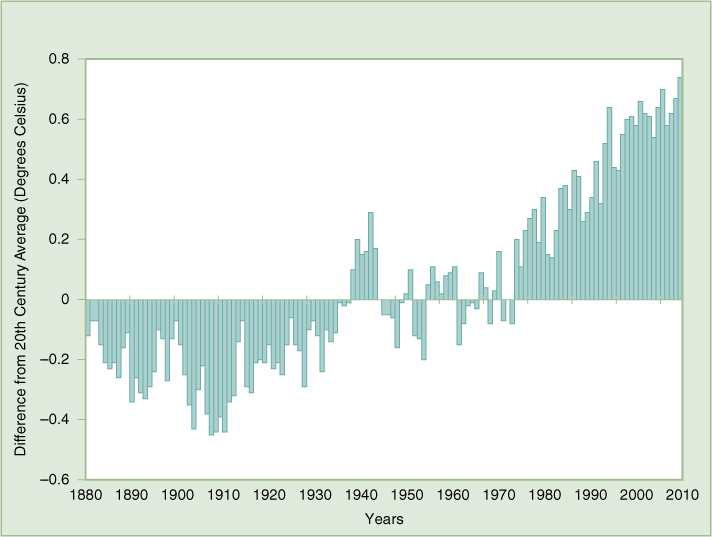

Studies of organisms newly introduced into a closed environment have shown two general patterns of population growth: the S curve and the J curve, illustrated in (FIGURE 25-1). Both patterns start out with a rapidly expanding population, but they differ in their response to environmental limitations. In the more common S pattern, environmental pressures increase gradually as the population approaches the number known as the carrying capacity—the number of organisms that can be supported in a given environment without degrading that environment. In the J pattern, the population expands rapidly past the carrying capacity and then crashes, because once the carrying capacity is exceeded, the environment is degraded, and the carrying capacity is reduced. For example, the J pattern is seen in lemmings and locusts, species famous for huge population explosions followed by massive numbers of deaths when the food supply is exhausted.1(Ch.2)

FIGURE 25-1 Patterns of Population Growth

Courtesy of of Lumen Learning. Openstax College, Population and Community Ecology. http://courses.lumenlearning.net/biology/chapter/chapter-19-population-and-community-ecology/. Accessed November 15, 2015.

It is not yet clear whether the human population is growing in an S or a J pattern. The world population has grown steadily, with minor irregularities, for the past million years, with a major surge beginning about 200 years ago. About that time, when the population of the Earth was about one billion, the British clergyman and economist Thomas Malthus raised an alarm that population growth was outpacing the food supply; he predicted that the resulting crowding would lead to famine, war, and disease. However, Malthus’s dismal predictions did not come about, and his warnings were discredited. Progress in agricultural technology and migrations from highly populated areas in Europe to the open spaces of the Americas and southern Africa relieved pressures on populations, allowing the expansion to continue.1(Ch. 21)

In 1968, when the world’s population was 3.5 billion, Paul Ehrlich, an American ecologist, published The Population Bomb, a best seller that repeated and expanded upon Malthus’s warning.2 Perhaps in part due to the attention paid to Ehrlich’s book, the rate of the world’s population growth has slowed since then, from an all-time high of 2.1 percent per year between 1965 and 1970 to 1.2 percent in 2015.3 There is a tremendous momentum to population growth, however, and the numbers continue to increase dramatically. In 1990, when the population had reached 5.3 billion, Ehrlich and his wife, Anne, published another book, The Population Explosion, arguing that many of his dire predictions have already begun to be realized.4 In 2004, with the world’s population at 6.4 billion, they published One with Nineveh, which further examines the consequences of overpopulation and the linked problems of overconsumption and political and economic inequity—consequences that include the prospect of increasing terrorism.5 Most recently, in 2010 when the population was approaching 7 billion, Paul Ehrlich, with Robert E. Ornstein, published Humanity on a Tightrope in which the authors argue that, in order to balance on the tightrope of sustainability suspended over the collapse of civilization, people need to recognize that we are all part of one family.6

Most environmentalists and public health experts agree with Ehrlich. However, like Malthus, he has his detractors. There are progrowth advocates—mostly economists—who argue that human ingenuity will always find ways of overcoming any problems created by crowding. In response, the Ehrlichs quote Kenneth Boulding: “Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”4(p.159) Some of the world’s major religions oppose population control measures, making it easier for politicians to listen to growth advocates and to simply ignore the problems created by overpopulation.

It is very difficult to predict what the world population will be in the future. There are indications, as the Ehrlichs point out, that environmental pressures opposing population growth are increasing, especially in developing regions of the world. There are also indications that international family planning efforts are paying off in slowing growth rates in many parts of the world. The United Nations predicted in 2015 that, if current trends continue, the population will reach 9.7 billion by 2050.3 The vast majority of the growth will be in the poorest countries of Africa and southern Asia. Projections after that are uncertain. It is not clear whether the Earth’s carrying capacity is large enough to support so many people. If not, irreversible forces may be building for a sudden J-type population crash. By the time the Ehrlichs would be proved right, it would be too late to do anything to prevent the disaster.

Public Health and Population Growth

Public health has had a major role in bringing about the dramatic growth in the world’s population over the past several decades. Public health improvements—clean water, immunization, pest control measures, inexpensive oral rehydration treatment of diarrheal diseases—in developing countries have led to major declines in death rates, especially among children. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) the number of children who die before reaching their fifth birthday declined by more than 45 percent between 1990 and 2010, and this number has continued to decline.7 Because birth rates remained constant, populations grew rapidly in the developing countries.

In developed countries, which instituted public health measures over a period of many decades in the 19th and 20th centuries, birth rates tended to fall in response to falling death rates, a process known as the “demographic transition.” The fall in birth rates is a rational response to parents’ knowledge that their children are likely to survive to adulthood. In an industrialized, urban society, children are an economic liability—expensive to feed, clothe, and educate.

In the developing world, however, many public health measures were introduced by international agencies over a short period of time after World War II. International aid for population control efforts has not been as generous. This is, in part, because of cultural resistance to contraception within some societies and, in part, because of the religious and political controversy surrounding family planning, especially in the United States, which has limited the amount of aid this nation provides.

Because of continued high birth rates, the public health in many developing countries is now, ironically, threatened by the crowding that has resulted from public health improvements. In all parts of the world, there has been a trend toward urbanization, because rural areas whose main industries are agricultural do not need the increasing numbers of workers. This trend has been most marked in developing countries, where migrants from rural areas flock to the cities. From 1950 to 2014, the percentage of people living in cities increased from less than one-third to over one-half; if current trends continue, the world will be two-thirds urban by 2050.8 According to the United Nations, the percentage of Africa’s population living in cities is 40 percent and is increasing at 1.0 percent per year, after a spurt of 2.4 percent increase per year between 1950 and 1970; Asia’s rate of urbanization is 48 percent and is increasing at 1.6 percent per year.8 Governments struggling to provide adequate drinking water and sewage services to their citizens cannot keep up with the influx. Many of the migrants settle on the outskirts of the cities in shantytowns totally lacking in water and sanitation. Others are completely homeless, simply living on the streets.

These conditions threaten to reverse all the progress in public health made through earlier efforts. Cholera and other diarrheal diseases are rampant in the third-world slums. Malaria and tuberculosis are also common. Intensive public health efforts have had some benefits. Immunization campaigns have reduced the incidence of measles, diphtheria, and other infectious diseases, including polio; in fact the World Health Organization announced in August 2015 that it had been a year since a case of polio was detected in Africa.9,10

The AIDS epidemic in Africa is waning, due to intensive efforts to provide antiretroviral treatment as widely as possible. In 2014, 41 percent of people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were receiving therapy. New infections fell by 41 percent and AIDS-related deaths by 48 percent between 2000 and 2014.11 Nevertheless, 4.8 percent of the adult population of sub-Saharan Africa is infected with HIV. In some countries, prevalence is shockingly high: In 2014 it was 31 percent of 18- to 49-year-olds in Swaziland12 and 18 percent in Botswana.13 The number of African children orphaned by AIDS is estimated at about 15 million.14 In fact, AIDS has dwarfed all other public health problems in Africa. Life expectancy in the hardest hit countries in southern Africa has fallen by up to 10 years, and the rate of population growth has decreased, although not enough to relieve the pressures of too many people.1(Ch.2),15

These desperate conditions in urban slums of developing countries lead to the disruption of traditional lifestyles and to the breakdown of normal social constraints, including sexual and parental restraints. Prostitution is common; children are abandoned to fend for themselves. These were the conditions that are believed to have led to the origin of AIDS as an epidemic threat, and they contribute to the continuing disaster of the epidemic. Such conditions may be the breeding ground for other emerging infections in the future. These conditions also encourage crime and violence. Even if, as predicted, population growth rates continue to decline, 95 percent of the 2 or 3 billion people added to the world in the next 25 to 50 years will be in the poorest countries, and most of that growth will occur in cities.1(Ch.2)

Even the United States and other developed countries are affected by some of the pressures described above, although the rate of population growth in this country is under 1 percent annually, and in Japan and most European countries, it is close to zero. Russia and some other Eastern European countries have negative population growth.3 The American population is becoming increasingly urban, with some 80 percent living in communities with more than 2500 residents.8 In 2013, 20 percent of American children lived in families with incomes below the poverty line; a high percentage of these children live with both housing and food insecurity.16

The United States is also affected by the social consequences of population growth in developing countries. Highly publicized problems with illegal immigration from Mexico and Central America are linked with poverty and with social problems caused by population growth in those countries. As conditions in those areas become more crowded and desperate in the future, the pressures on people to seek less crowded, more prosperous surroundings will increase, making it more difficult for the United States to remain isolated. Infectious diseases have no respect for political boundaries. With international travel and commerce so rapid and widespread, Americans are at risk from diseases imported from anywhere in the world. Furthermore, as discussed in the following section, human population growth threatens to change the environment of the entire globe, posing health threats that no one could escape, even if the nation’s borders were sealed.

Global Impact of Population Growth—Depletion of Resources

The carrying capacity of the Earth—the population size that the Earth can support without being degraded—is determined by a number of factors, some of which can be altered by technological intervention and human behavior. These factors, which are related, include the availability of fresh water, the availability of fuel, the amount and productivity of arable land, and the amount and disposition of wastes, both biological and technological. There are signs that the carrying capacity is already exceeded in some parts of the world: As the environment is degraded, the size of the population that can be supported shrinks, leading to further environmental degradation and a vicious circle of hunger, disease, and death.

The supply of fresh water, which is basic to human life, is one of the factors that limits the Earth’s carrying capacity. Water is essential for drinking, cooking, and washing. It is also used for agriculture, irrigating dry fields to grow the increasing amounts of food required by expanding populations. Water is a renewable resource, due to cycles of evaporation and precipitation, but the rate at which water supplies are renewed is fixed. Only a small percentage of the water on Earth is suitable for human use: While there are methods of removing the salt from sea water, the technology is expensive and uses large amounts of energy. Pollution resulting from the use of fresh water supplies for disposal of wastes also renders potential sources of water unsuitable for human use.

Availability of fresh water is highly variable according to geographic area and precipitation patterns. In drier parts of the world, especially the Middle East, water rights become volatile international issues because some countries depend on water sources that originate beyond their borders. For example, the Nile flows into Egypt from Ethiopia and Sudan, and the flow of the Tigris–Euphrates into Syria and Iraq may be altered by dam construction in Turkey.

In the United States, water supplies have been sufficiently plentiful so that Americans are accustomed to lavish consumption, watering lawns, washing cars, and filling private swimming pools, even in relatively dry areas of the Southwest. For example, much of the water used in that part of the country comes from the Ogallala Aquifer, the world’s largest underground water reserve, which underlies portions of six southwestern states. This water accumulated during the last ice age and cannot be replenished. Yet it is being used, among other things, for industry and irrigation, attracting people to the area who will be left literally high and dry when the water runs out.1(Ch.15)

California, too, is used to an abundant supply of water provided by snow melt from the Sierra Nevada mountains. However, after several years of record hot and dry weather, as well as snow-less winters in the Sierras, wells were going dry in some parts of the state and wildfires burned out of control. Governor Jerry Brown declared a state of drought emergency in January 2014 and called for a 20 percent voluntary reduction in water use.17 In April 2015 Governor Brown ordered a mandatory 25 percent reduction in water use.18 Communities have begun efforts at desalination of seawater and recycling of wastewater. Lawns have been replaced with rocks and cactus. Gardens and golf courses have needed to find ways to get by with less water. Since 80 percent of the state’s water goes to agriculture, farmers needed to develop more efficient irrigation methods. Meanwhile, California’s population continues to grow and there is no prospect that California will grow wetter.19,20

The amount of fresh water on Earth is theoretically sufficient to support a population of 20 billion people if evenly distributed.21 Many countries have taken steps to conserve fresh water supplies and to clean up the pollution. In poorer, drier countries, however, the available water is insufficient to support the growth in population that is occurring. The lack of water for cooking and washing, and the pollution of drinking water with human and industrial wastes, is already harming the public health. According to the United Nations, 40 percent of the world’s people, mostly in Africa and south Asia, live in regions with water shortages, and that number will grow to two-thirds by 2025.1(Ch.15)

Predictions about the Earth’s carrying capacity have most often centered on food, attempting to estimate the limits of agricultural productivity. Malthus’s warnings were built on concerns about limited growth in food supplies, which nevertheless continued to grow rapidly for almost two centuries. Now, unhappily, it is beginning to look as if Malthus may finally be proven right. According to the United Nations’s Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO), in 2015 about 11 percent of the world’s population were chronically or acutely malnourished. In sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of hunger is about 23 percent and in southern Asia it is 16 percent.22

With increasing populations needing greater amounts of food, the amount of land used for agriculture grew quickly during the period between 1850 and 1950. Then, despite continued population growth, the expansion of arable land slowed down and ceased altogether in the late 1980s.23 Food production continued to keep pace with population growth during the 1960s and 1970s, however, because of the “green revolution,” the development of genetic strains of wheat and rice that yielded harvests two to three times greater than conventional strains. Crop yields also grew because of increasing use of fertilizers, irrigation, and chemical pesticides.

Such increases in yields are unlikely to continue, however, because of water shortages, depletion of soil, and the development of resistance by pests to chemical pesticides. The amount of land under cultivation has declined in some parts of the world, especially Africa. According to one estimate, 40 percent of the world’s agricultural lands are strongly or very strongly degraded.1(Ch.5) In part this is because of spreading urban centers, in part it is because the soil is depleted of nutrients or has become salty from irrigation. Erosion of topsoil due to overgrazing and poor agricultural practices contribute to the loss of arable land. The demand for agricultural land for farming has led to widespread clearing of forests, although forested land may be only marginally suitable for cultivation. Deforestation also occurs as a result of people gathering wood for fuel. The need by growing populations for firewood for cooking and, in colder climates and mountainous regions, heating as well, has resulted in vast treeless areas around towns and villages throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The loss of forests increases soil erosion and contributes to catastrophic flooding in areas subject to monsoons.1(Ch.5)

Population growth has also caught up with the seemingly limitless supply of food from the sea. Fish catches increased dramatically between 1950 and 1989 but have declined since then. The UNFAO has concluded that 75 percent of the major marine fish stocks are fully exploited, overexploited, or significantly depleted. Pollution of coastal waters has also contributed to the decline of harvests, especially those of shellfish. On the bright side, the practice of aquaculture is growing rapidly, and by the early 21st century almost half of all fish eaten worldwide was raised on fish farms.1(Ch.4) There are drawbacks to fish farming, however. Farmed salmon, for example, are fed fish meal and fish oil made from large amounts of smaller fish such as sardines, anchovies and herring, thus depleting fisheries that might otherwise feed people. The waste from penned fish pollutes coastal waters. Saltwater fish farms incubate microbes and parasites that threaten to infect wild stocks.

Global Impact of Population Growth—Climate Change

Perhaps the most threatening effect of population growth is that it is beginning to change the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere, with potentially drastic consequences. The depletion of the ozone layer, which protects the Earth’s surface from ultraviolet radiation, is known to increase risks in humans of skin cancer, melanoma, and cataracts. It may also have a harmful impact on plant and animal life.

Although international agreements have led to policies effective in slowing and possibly even reversing damage to the ozone layer, there is less hope of preventing climate change caused by other human activities. Alteration in the relative concentrations of the four major constituents of air—nitrogen, oxygen, argon, and carbon dioxide—is causing global warming due to the “greenhouse effect,” in which the energy of sunlight is absorbed by carbon dioxide in the air and turned into heat rather than radiating back into outer space.

The balance of atmospheric gases has been maintained over the millennia by the photosynthetic activities of green plants, which take up carbon dioxide and release oxygen. The reverse process occurs during combustion of wood, coal, oil, and gas: Oxygen is consumed and carbon dioxide is released. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, with the ever-increasing use of fossil fuels, the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have been rising. The trend is made worse by the loss of photosynthetic action that accompanies widespread destruction of forests through logging and, worse, by the burning of vegetation, including tropical rain forests, to clear land for agriculture and human settlement. Green plants are being lost from the ocean also, through poisoning of phytoplankton by pollution of the seas. The concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide has grown by over 35 percent since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and is continuing to grow at an increasing rate.24 Other gases also contribute to the greenhouse effect, especially methane, which is released by microbial activity in the intestines of cattle and in paddy fields where rice is grown.

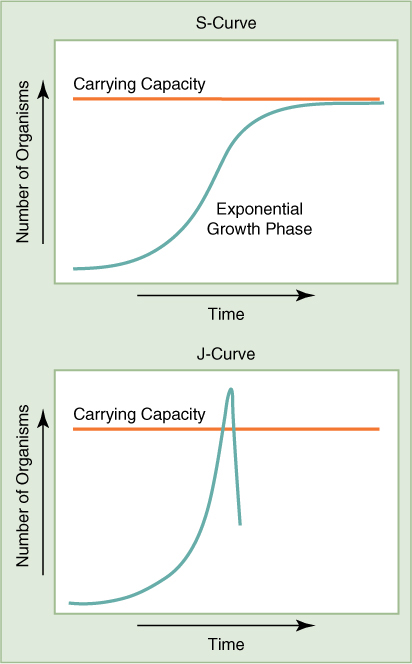

Although the evidence was strongly disputed for many years, it is becoming increasingly clear that global climate change has begun: The Earth’s average combined land and ocean temperature had risen by well over one full degree Fahrenheit over the past century, as seen in (FIGURE 25-2). Predictions for the year 2100 range from 3 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than today.24 The temperature increase is widespread over the globe and is greatest in the northern arctic region. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 along with former vice president Al Gore, the effects of global warming are already being felt. Sea levels rose during the second half of the 20th century and have continued to rise as glaciers and Arctic ice sheets melt. The IPCC predicts a rise of 1 to 2.7 feet by the end of the 21st century. Shifting precipitation patterns have increased dryness in the southwestern United States, northern Mexico, the Mediterranean region, and sub-Saharan Africa, while increasing wetness in northern North America and northern Europe.23 The California drought that began in 2012 and continued at least through 2015 is due, at least in part, to global warming.25