and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

12.1 Definition, Site and Incidence

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) is almost exclusively a minor salivary gland tumour and has been recognised since the early 1980s. It shares many similar histological patterns with adenoid cystic carcinoma, but the biological behaviour is significantly different. The term polymorphous low–grade adenocarcinoma was coined by Evans and Batsakis in 1984 [31] when reporting a series of 14 cases of a salivary gland tumour with new distinctive histological features. The tumour had before 1984 been described under other names, such as trabecular carcinoma [108] and also lobular carcinoma due to resemblance to breast lobular carcinoma [36]. In 1983, Batsakis and associates originally designated this tumour terminal duct carcinoma as it was (and still is) regarded to arise from the terminal duct (intercalated duct) [9]. The term polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma was later adopted in the 2nd WHO classification of 1991 and defined as ‘a malignant epithelial tumour characterized by cytological uniformity, morphological diversity and a low metastatic potential’ [101]. By 1991, only approximately 130 cases of PLGA had been reported in the English literature [47], but since then several large series have been published, and the largest series to date was published in 1999 and that alone comprised 164 cases [13]. PLGA is nowadays widely recognised and considered to be the most common malignant intraoral salivary tumour second to mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Although the clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of PLGA have been reported in detail over the years, the diagnosis of this entity remains difficult in many instances [4, 20, 22, 23, 26, 38, 42, 43, 47, 52, 57, 78, 90, 93, 95, 119, 122, 123, 128]. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma is characterised histologically by a bland cytological uniformity combined with a remarkable histological diversity (tubular, papillary, cribriform, solid and fascicular growth patterns) and clinically as an indolent tumour, invasive and locally persistent but slow to metastasise. The main differential diagnosis is from adenoid cystic carcinoma, but PLGA can also be confused with papillary cystadenocarcinoma and both pleomorphic adenoma and sometimes even carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. PLGA is almost exclusively a neoplasm of minor salivary glands. To date, only approximately 35 parotid cases have been reported [41, 58, 69, 71, 80, 91, 94, 97, 114]. Most if not all of these cases appear to have arisen ab initio in the parotid gland, but parotid PLGA has also been reported as the carcinomatous component in carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Ten of the 40 carcinomas ex pleomorphic adenomas reported by Tortoledo and associates were described as terminal duct carcinomas (PLGAs) [112]. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma is extremely rare in the other major salivary glands with only the odd case arising in the submandibular gland [76] and the sublingual gland [127]. In 1999, the huge files of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology were searched but not a single case of PLGA arising in a major salivary gland was revealed [13], which indeed emphasises that PLGA virtually is a minor salivary gland tumour only. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma does not have a tendency to be multifocal, but the odd cases of simultaneous multifocal intraoral PLGA have been described [18]. On rare occasions, PLGA have been reported in the nasopharynx [39, 121, 122], maxillary sinus [14, 30], tongue [24, 45, 59], tonsil [88], vulva and vagina [126] and the lung and bronchus [11, 15, 62]. Only four cases of intraosseous PLGA appear to have been reported, two in the mandible [25, 92] and possibly two in the maxilla [40, 98]. The origin of intraosseous PLGA, and of salivary gland tumours in general, is thought to be from the ectopic salivary gland tissue. Neoplastic transformation of mucous cells of the epithelial lining of dentigerous cysts or odontogenic epithelium has also been proposed [33].

The largest series of PLGA up to date is that of 164 cases reported by Castle and associates [13] and which were selected from 172 cases identified as PLGA in a review of 11,236 benign and malignant primary salivary gland tumours (1970–1994). Hence, at this institution (AFIP) at that time period, PLGA represented 1.5 % of all salivary gland tumours, benign and malignant, and from both minor and major salivary glands. A very crude estimate after comparison of these data with those of other centres concludes that PLGA constitutes probably 10–20 % of malignant intraoral malignancies. In another study from AFIP, Ellis and Auclair [28] reported PLGA to constitute 19.6 % of malignant tumours of minor salivary gland origin seen at the AFIP since 1985. Other studies from the USA, albeit from smaller registers, indicate that in Northern California PLGA constituted 7.1 % [12] and in Oregon as much as 19.1 % [125] of malignant intraoral salivary gland tumours. In a Chinese population, PLGA represented 8.6 % [120] of 397 malignant minor salivary gland tumours. Another study from Asia (Thailand) also described a lower incidence of PLGA compared to many reports from the USA or Europe [21]. In a series of 185 minor salivary gland tumours in India, PLGA constituted 10 % [117]. Jones and associates [56] reported a large series of salivary gland tumours (741 cases) in a UK population. PLGA constituted 3.8 % of all tumours in major and minor glands, 10.8 % of all malignant salivary gland tumours and 16.3 % of all malignant minor salivary gland tumours. PLGA is hence in most countries the second most common malignant intraoral tumour, mucoepidermoid carcinoma being the most common. PLGA belongs to the ‘group of the big six’ (mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, acinic cell carcinoma, PLGA and salivary duct carcinoma), tumours that together represent 85–95 % of all major and minor salivary gland malignancies.

Most patients are between 50 and 60 years of age with a range from 22 to 94 years, and the female to male ratio is approximately 2:1 [13, 32, 53, 56, 60, 65, 85, 115, 118]. PLGA has however very occasionally been described in children [113]. The palate is the most common site followed by the lips (particularly upper lip), then the buccal mucosa and the alveolar ridge. In the study by Castle and associates [13], 32 % of cases were located in the palate, 13 % in the lips, 10 % in the buccal mucosa, 8 % in the alveolar ridge and the remaining 4 % at other mucosal sites. These figures are in agreement with other studies [125]. Yet other studies have, however, indicated an even more propensity for PLGA to arise in the palate and also that the hard palate is a more frequent site than the soft palate [2, 37]. In the series of 40 cases of PLGA reported by Evans and Luna [32] 60 % of cases arose in the palate, whilst 65 % of cases were palatal in the series published by Luna and co-workers [67]. Similarly, Seethala and associates reported 58 % of their 24 cases to be palatal in origin [100]. Buchner and associates [12] reported 78 % (21 of 27 cases) and in the study by Wang and associates [120] as much as 82 % (28 of 34 cases). It is hence evident that PLGA is almost exclusively a tumour of minor salivary gland origin and also that the (vast) majority arises in the palate.

The clinical presentation of PLGA is typically a slowly growing asymptomatic mass located within the oral cavity. In the series of Castle and co-workers [13], the tumours ranged in size from 0.4 to 6 cm with an average of 2.2 cm. Lip tumours were 1.1 cm smaller than palatal tumours, probably reflecting the relative ease of clinical visualisation of lip tumours versus the palatal ones. Pain and/or ulceration were present in 8 % of cases.

12.2 Histopathology

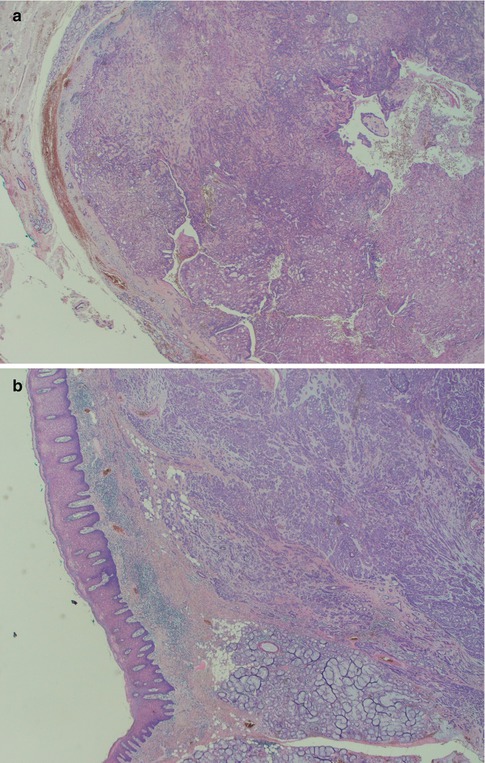

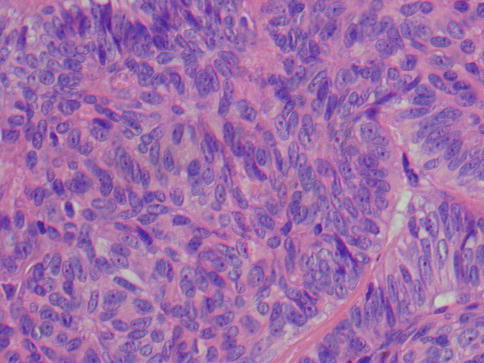

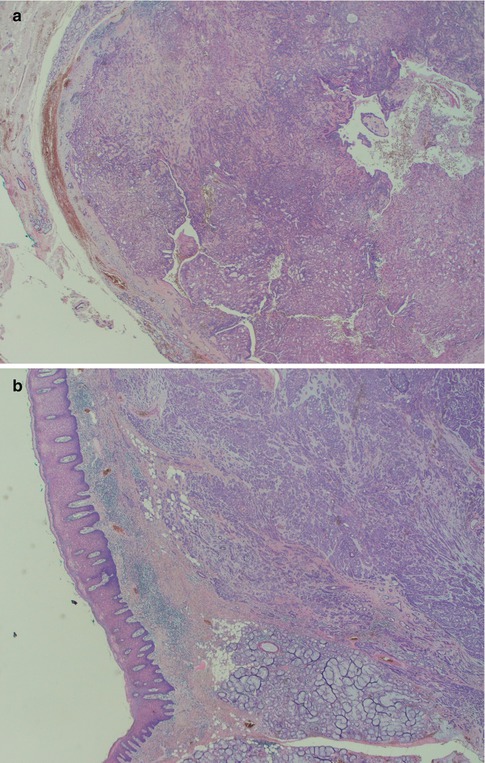

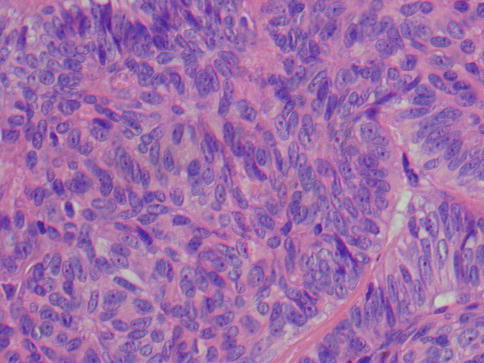

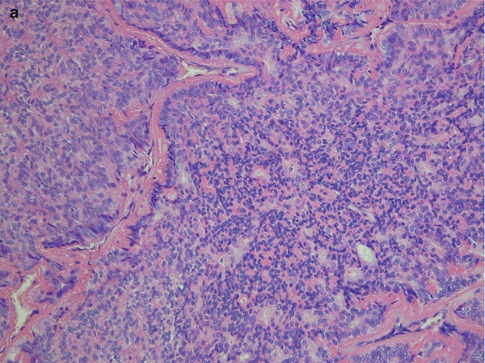

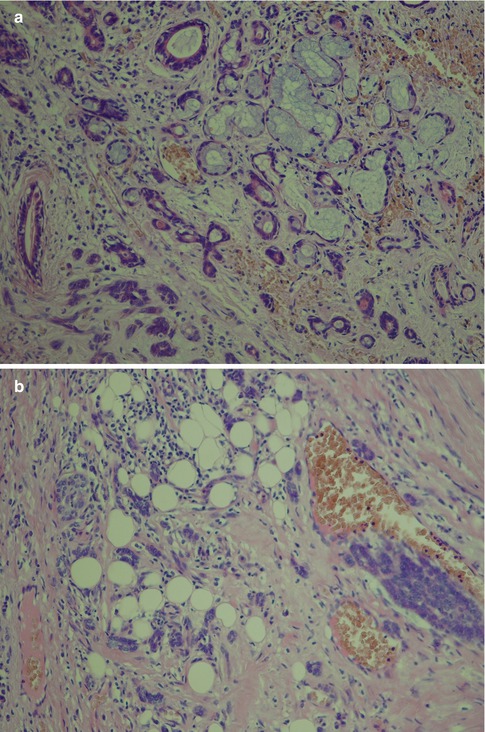

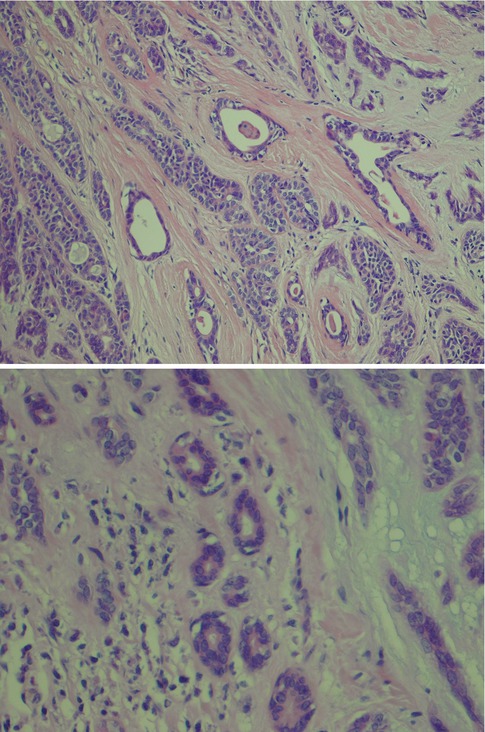

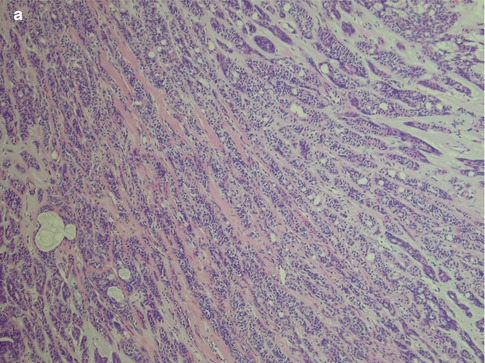

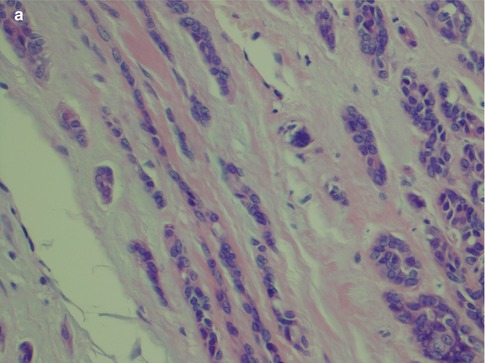

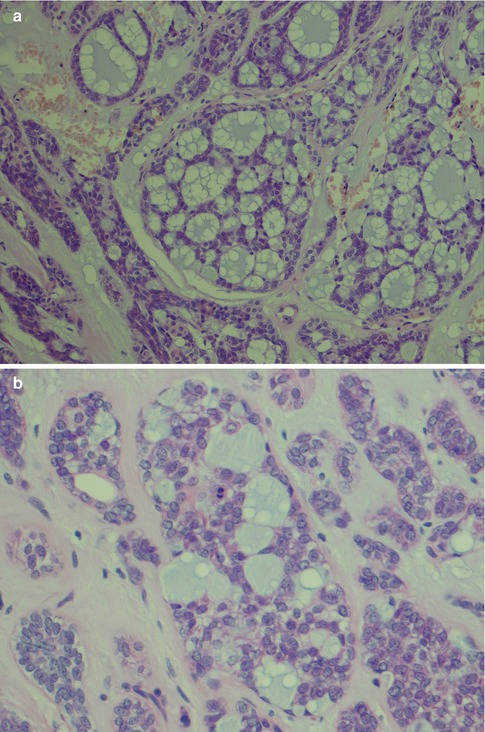

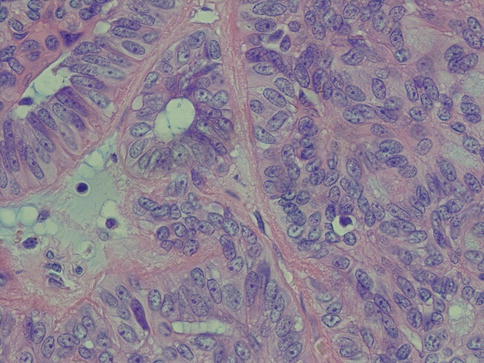

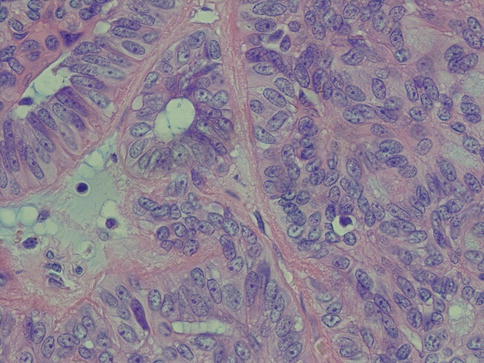

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinomas can be well circumscribed but are not encapsulated tumours. On low-power examination, PLGAs frequently appear well circumscribed but focally invasive (Fig. 12.1). The great variety of histological growth patterns within any one tumour and the very bland cytological features are the hallmarks of PLGA. The cytological features resemble those of a benign tumour rather than a malignant neoplasm. There are areas with cells that are closely packed giving the neoplasm an appearance of crowded, partially overlapping cells similar to what can be seen in myoepithelioma and pleomorphic adenoma (Fig. 12.2).

Fig. 12.1

(a) Low magnification shows the tumour to be partially circumscribed but not encapsulated. (b) Focal infiltration with small lobules and islands of tumour cells

Fig. 12.2

PLGA consisting of closely packed cells with bland cytological features

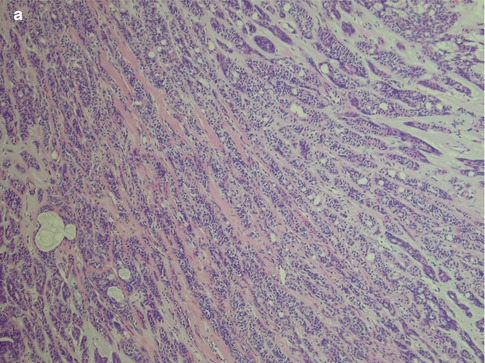

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma shows a striking histological diversity with several different growth patterns within and amongst cases. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is usually described as having three growth patterns, namely, solid, cribriform (glandular type also comprising ‘punched out holes’, microcysts) and tubular. These three are dominating features of PLGA as well, but there are also trabecular, papillary, single-file (Indian file) and fascicular patterns. These growth patterns have been categorised by slightly different wordings over the years, and originally Evans and Batsakis [31] described solid, tubular, papillary, cribriform (pseudoadenoid cystic) and fascicular growth patterns. Luna and associates [67] used the terms solid, tubular, cribriform, papillary and fascicular, whilst Ellis and Auclair [28] characterised the patterns as solid, trabecular, ductular, tubular, cribriform, cystic and papillary-cystic. Perez-Ordonez and associates [86] described the growth patterns as tubules and small duct-like structures, cords and trabeculae, solid nests, cribriform and papillary. Castle and associates [13] preferred the terms glandular, tubular, trabecular, cribriform and linear (single cell). Evans and Luna reviewed the files again of the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in 2000 and used the words solid, tubular, microcystic, cribriform (with true lumens), pseudoadenoid cystic (without true lumens), fascicular, papillary, single-file and strand-like [32]. In 2006, Pogodzinski and co-workers [89] reviewed the files of the Mayo Clinic and termed the growth patterns as solid, cribriform, tubular, trabecular, fascicular and papillary. They are all descriptive terms and anyone will do as well as another. The importance lies in recognising the variable combinations of several of these growth patterns which hence characterise PLGA. The tumour cells may also show metaplastic changes and the collagenous stroma may be mucoid, hyalinised or mucohyaline, yet other features emphasising the polymorphous nature of PLGA.

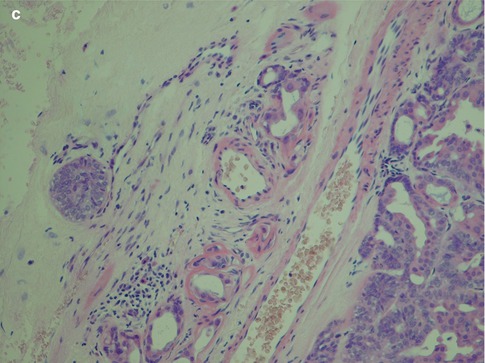

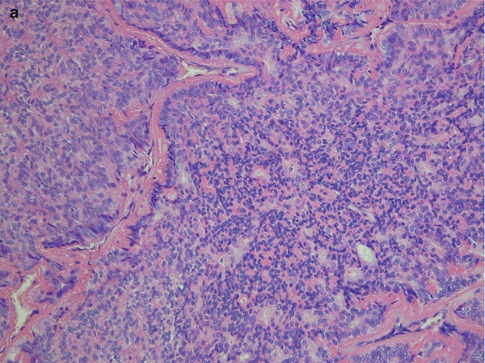

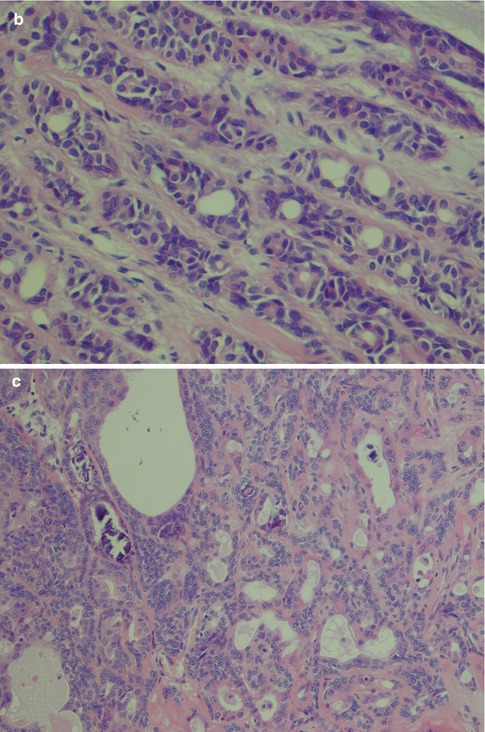

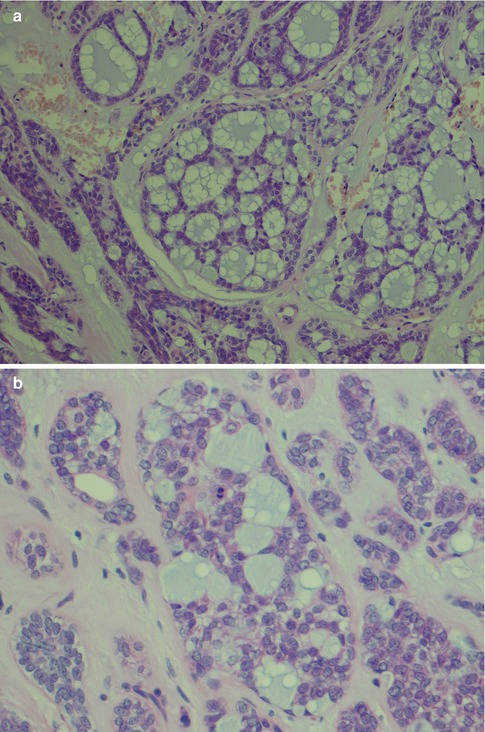

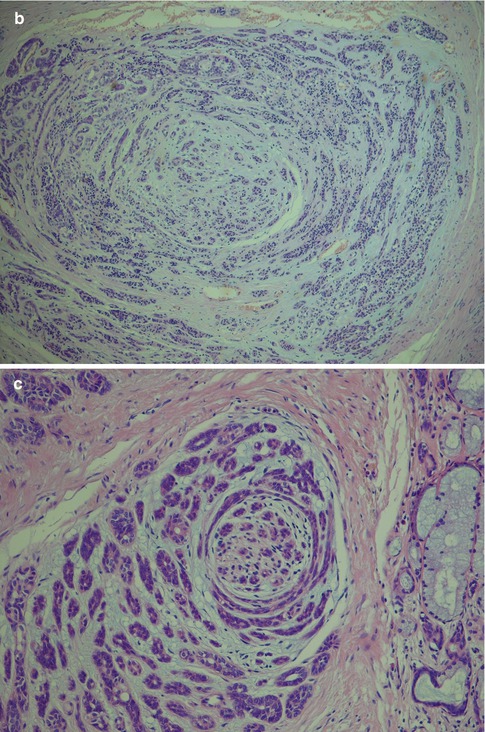

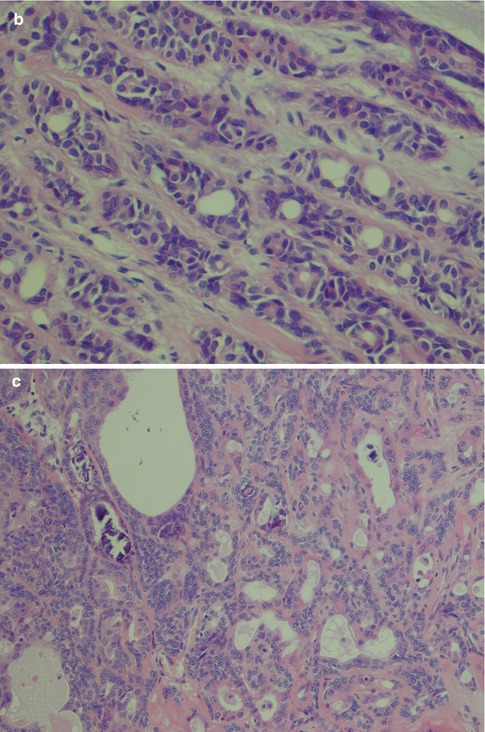

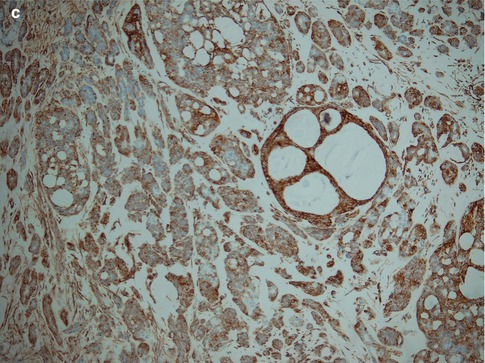

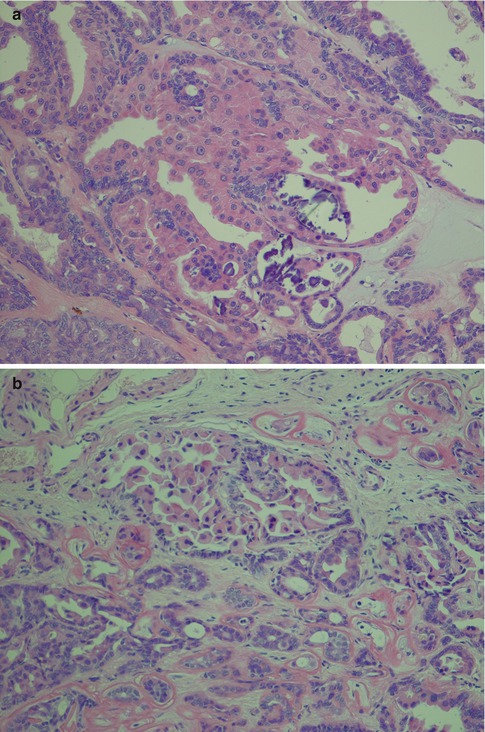

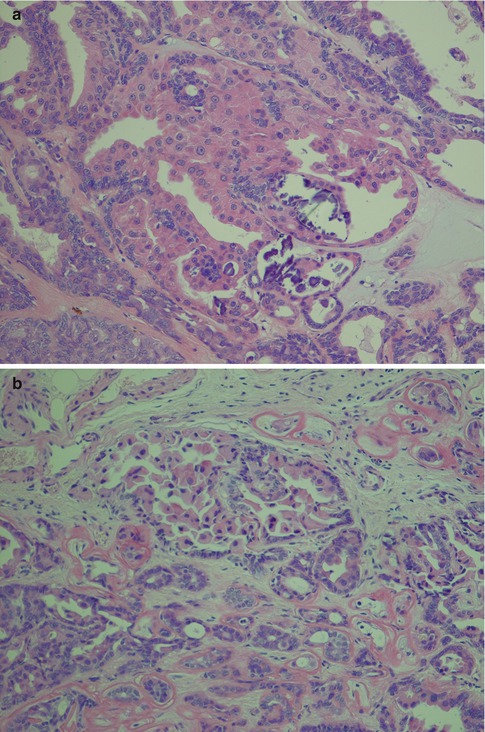

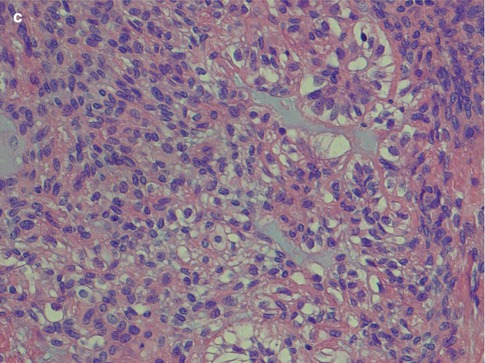

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma consists of luminal and non-luminal cells. Their relative proportion and distribution will create a variety of morphological patterns. The non-luminal cells are characteristically pale round, oval or spindled and regular with finely dispersed chromatin. There are inconspicuous or small, single nucleoli. A predominance of non-luminal cells will form solid nests and cribriform areas with pseudoluminal spaces. Tumours with solid tumour nests thus consist primarily of non-luminal cells creating solid tumour nests of varying sizes. The cells are often closely packed and sometimes appear to be lying on top of each other and giving a blurred, out-of-focus appearance in the microscope. The cells are cytologically bland, and the angular nuclei and atypia seen in solid nests of adenoid cystic carcinoma are not present. The islands are often separated by thin cords of stroma and can be arranged in a lobular fashion. The peripheral cells of the tumours island can be seen to be palisading (Fig. 12.3). Necrosis is very rare in PLGA but occasionally appears in solid areas as comedo-type necrosis. Mitotic activity is inconspicuous. Predominance of luminal cells will create tubules and small duct–like structures that have distinct central lumens lined by a single layer of often cuboidal cells. The luminal cells exhibit ductal differentiation and show moderate or strong expression of LMWK, S-100 and vimentin with weak or negative expression of CEA and EMA and only occasional staining for HMWK [86]. They contain intraluminal mucin and may be seen in a hyalinised stroma (Fig. 12.4). These tubules and ductal structures do not have two cell layers as seen in pleomorphic adenoma. The lack of a surrounding layer of myoepithelial or basal cells can be highlighted by immunostain for p63 or other basal/myoepithelial markers (Fig. 12.5). Groups of small tubular structures with bland cytology that infiltrate and partly replace the surrounding minor salivary gland tissue are a characteristic feature of PLGA. Small tumour nodules separated away from the main tumour constitute another feature of PLGA (Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.3

(a) Solid nests of tumour cells separated by a collagenous stroma and faintly outlined palisading of peripheral cells. (b) Solid area with crowded appearance, no mitoses and no necrosis. (c) Solid growth pattern with a slightly fascicular arrangement of cells, some of which are spindle-shaped rather than round or oval

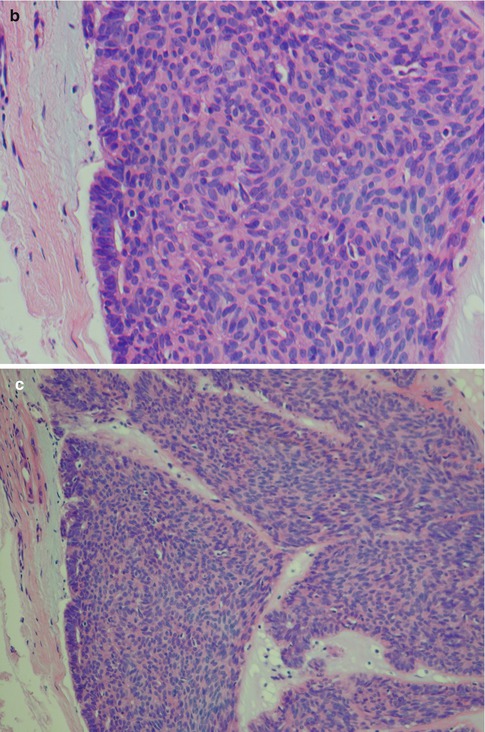

Fig. 12.4

(a) Three larger tubules or duct-like structures separated by a fibrous stroma. There are also tubules as well as pseudocysts in the cellular trabeculae. (b) Higher magnification showing tubules (true cysts) lined by one cell layer only

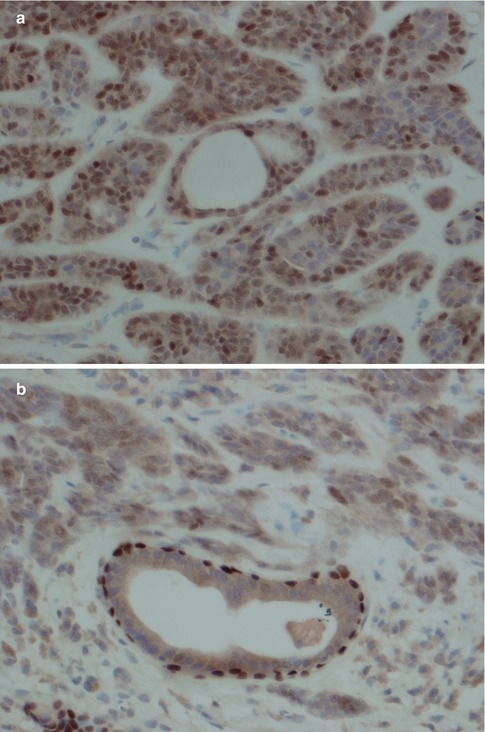

Fig. 12.5

(a) PLGA stained with p63. In the centre a duct structure with one cell layer only. (b) For comparison a normal duct entrapped in the same tumour showing p63 staining of outer surrounding myoepithelial cells

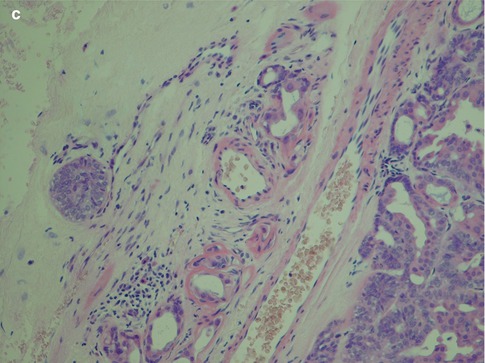

Fig. 12.6

(a) Neoplastic tubules infiltrating adjacent minor salivary tissue. (b) Diffuse infiltration into the surrounding fat of very small clusters of tumour cells. (c) A satellite tumour nodule (left) separated from the main tumour

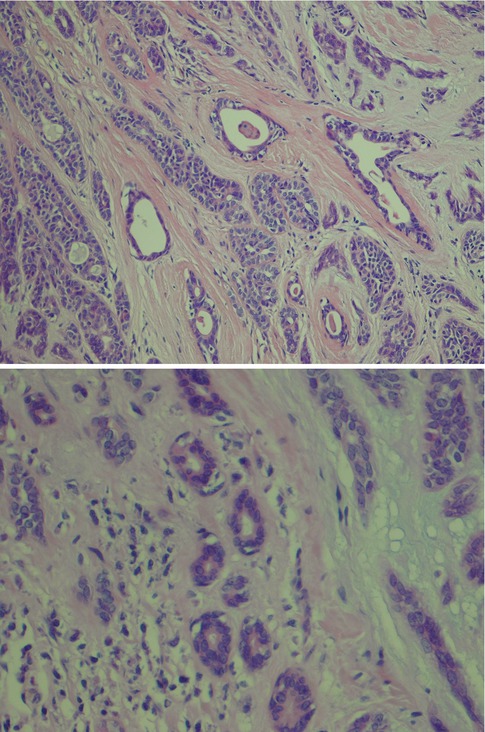

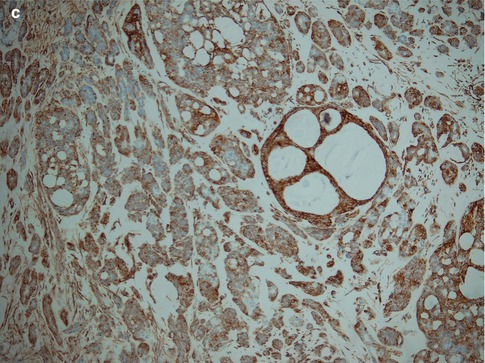

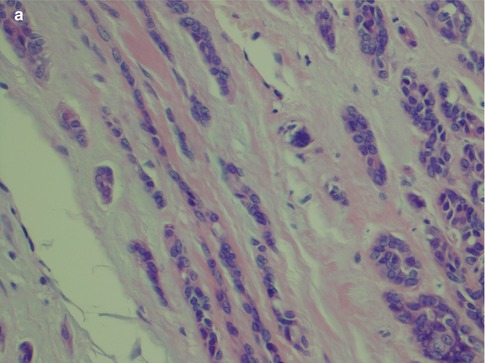

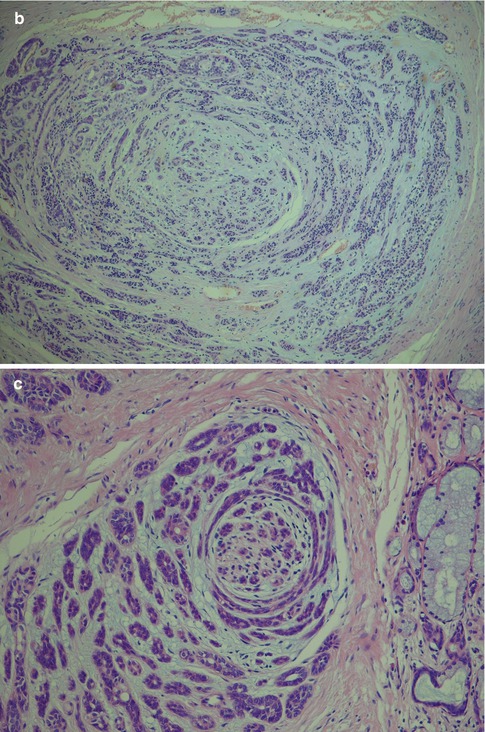

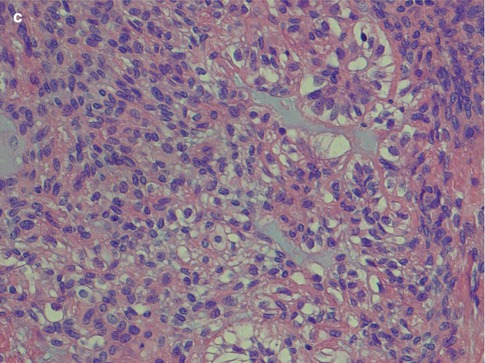

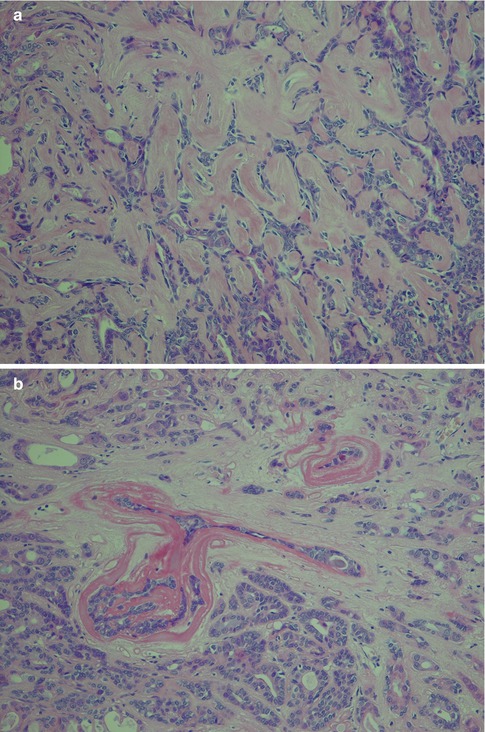

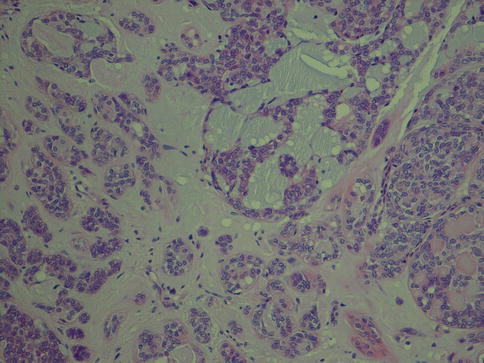

With an increased number of non-luminal cells in relation to luminal cells, growth patterns of cords and trabeculae will be seen. The cords and trabeculae hence consist predominantly of non-luminal cells. These often streaming rows of cell clusters have numerous cystic spaces (punched out holes, pseudoadenoid cystic) and to a lesser degree are also true duct structures. Intratubular calcifications are not infrequent, whilst luminal crystalloids only rarely can be seen as eosinophilic crystalline material in glandular spaces (Fig. 12.7). Cribriform areas consist of non-luminal cells that form prominent pseudoluminal spaces as seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma. These areas are very similar to the typical appearance of adenoid cystic carcinoma, but the cells are cytologically bland and not as basaloid and atypical as seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Necrosis may occasionally be seen in PLGA and is hence not a distinguishing factor for adenoid cystic carcinoma (Fig. 12.8). PLGA has a high tendency for single-cell invasion consisting of individual or two to three cells arranged in thin rows, so-called ‘Indian file’ pattern. The tumour cells are often arranged concentrically around a central nidus, creating a targetoid appearance. Neurotropism is frequently present, and the nidus is often a small nerve (Fig. 12.9).

Fig. 12.7

(a) Trabecular growth patterns with streaming rows and cords of non-luminal cells with tubules and pseudocysts. (b) Higher magnification shows tubules or ductal structures but also pseudocysts. (c) Several intratubular calcifications

Fig. 12.8

(a) Cribriform patterns with pseudoluminal spaces (‘pseudocysts’) with bubbly appearance and typical bluish colour. (b) Higher magnification demonstrating bland tumour cells but also a mitotic figure. The cells in a corresponding cribriform area of adenoid cystic carcinoma would show considerably more atypia. (c) PLGA is uniformly positive for vimentin with cribriform pattern highlighted in the centre

Fig. 12.9

(a) Streaming rows of single-cell invasion (Indian file pattern; left). (b) Targetoid appearance with tumours cells arranged concentrically around a nidus of tumour cells. (c) Perineural invasion with similar targetoid appearance around a nerve

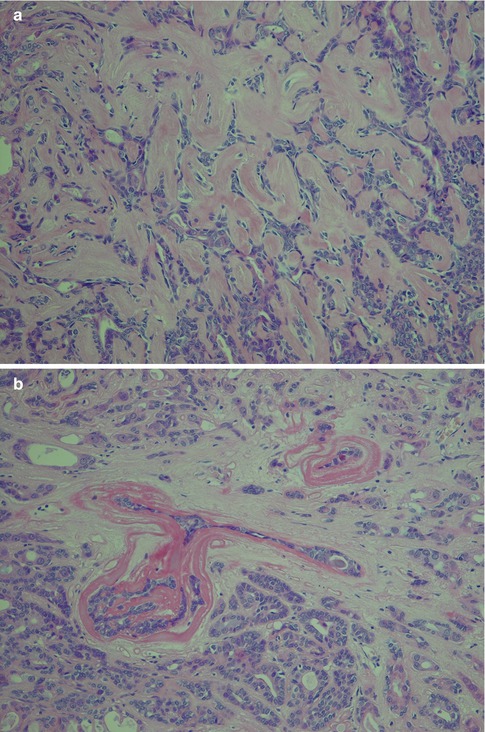

Papillary and cystic areas can be prominent and frequently display oncocytic metaplasia. Mucinous or clear cell metaplasia can also occur (Fig. 12.10). In yet other cases, the papillary pattern is very scarce or absent and to the extent that they have been described as a non-papillary subtype of PLGA [37]. The stroma can be hyalinised to various degrees and sometimes almost sclerotic (Fig. 12.11). The hyalinised stroma is often slightly eosinophilic in certain areas whilst mucohyaline or mucoid-myxoid in others, adding to the polymorphous appearance. The latter is typical for PLGA and appears as a slate blue-grey stroma that does not resemble the mucoid-myxoid matrix of pleomorphic adenoma but rather that of adenoid cystic carcinoma (Fig. 12.12).

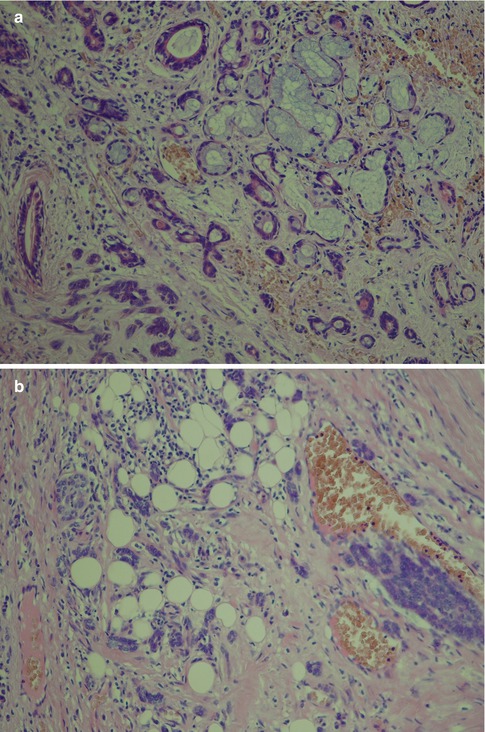

Fig. 12.10

(a) Oncocytic metaplasia, partly papillary patterns and calcifications. (b) Papillary growth pattern of partly oncocytic cells. (c) Clear cell metaplasia

Fig. 12.11

(a) PLGA with a hyalinised stroma. (b) Marked hyalinised stroma around individual tumour nests

Fig. 12.12

PLGA with a mucoid blue-grey stroma

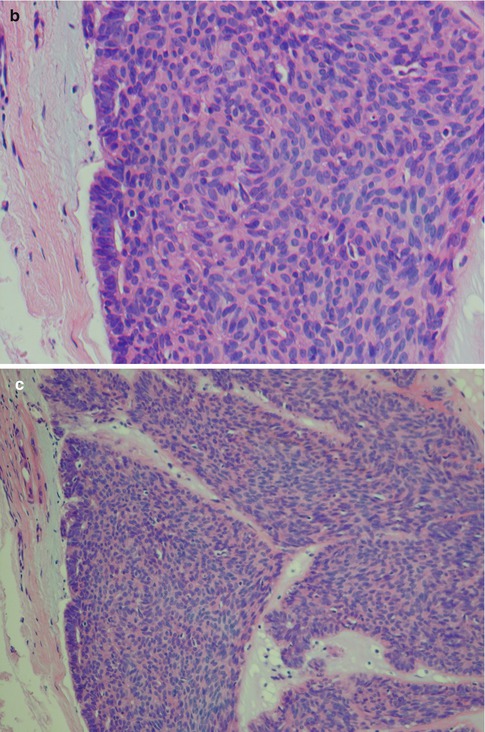

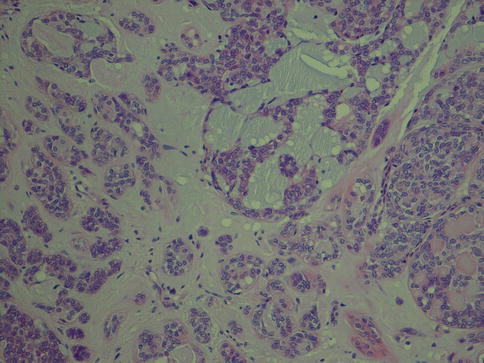

Transformation of PLGA to high-grade carcinoma (dedifferentiation previously being the preferred term) is very rare, and less than ten cases are described in the literature (see also Chap. 16). These tumours underwent transformation to poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas with predominantly solid and cystic growth pattern and foci of necrosis. The cells had lost their typical bland cytology and showed atypia with prominent nucleoli [19, 63, 72, 74, 83, 103] (Fig. 12.13).

Fig. 12.13

Transformation into vesicular nucleoli with prominent nucleoli

The so-called cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue described by Michal and associates [70] is by some regarded as a variant of PLGA, yet by others as a separate entity. There is some histological overlapping, but the demographic and clinical features are not typical of PLGA; in fact, they would be unusual to represent a subtype of PLGA. The eight cases of cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue described by Michal and associates [70] were all hence located in the tongue which is not a common location for PLGA. Furthermore, the typical female predominance of PLGA was not apparent and all eight patients presented with synchronous metastases in lateral neck lymph nodes. Further, in 2011 an additional study, now consisting of 23 cases (not all in the tongue), was published and that further supports cribriform adenocarcinoma to be a separate entity [105]. Therefore, at the time being, it seems more prudent to regard cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue as an entity not related to PLGA, and a brief description of its features is given in Chap. 14. Low–grade papillary adenocarcinoma (LGPA), on the other hand, has been described as a rare variant of PLGA but also at the same time distinct from PLGA [51]. The low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma is considered to be oncologically distinct from PLGA in being more aggressive than conventional PLGA. Low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma was first described by Allen and associates in 1974 and later by Mills and associates in 1984 [3, 72]. Further work by Brandwein-Gensler and associates suggested that a cutoff value of 10 % or greater papillary formation is necessary to separate LGPA from PLGA, as at the moment uniform diagnostic criteria for LGPA are lacking [51]. It may be worth to remind ourselves that in the early 1990s the issue of papillary low-grade oral tumours was discussed and illuminated by Slootweg. The designation papillary low-grade adenocarcinoma was used for polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma with papillary structures as well as for papillary cystadenocarcinomas. Personally, we are inclined to agree with his conclusion that the use of the diagnosis of papillary low-grade adenocarcinoma should be discontinued. The terms papillary low-grade adenocarcinoma and low-grade papillary adenocarcinoma are confusing in relation to polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Slootweg’s recommendation is also in agreement with that of the latest WHO classification of 2005, i.e. to continue to term these tumours cystadenocarcinomas (with or without papillary structures) contrasting to polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) [8, 66, 106].

12.3 Molecular Pathology

Several studies have indicated that the neoplastic cells of PLGA in the vast majority of cases are positive for cytokeratin (100 %), vimentin (100 %) and S-100 (97 %). They are also positive for CEA (54 %) and for EMA, SMA and GFAP in 12–15 % of cases. The data above are given in the 2005 WHO classification [66], and reference was given to studies performed in the late 1980s and in the 1990s [13, 86, 122] and in particular the 164-case large study by Castle et al. from 1999. It that study, however, although the study comprised 164 cases of PLGA, immunohistochemistry was only performed on 39 of those cases [13]. During the last 10 years, several molecular, genetic and immunohistochemical studies have been performed and consequently more knowledge obtained. Recent studies have indicated that PT53 mutations are not a frequent event in salivary gland tumours, benign as well as malignant [44]. Similarly, no amplification/overexpression of HER2 is seen in PLGA [16]. The translocation t(11;19)(q21;p13) involving the MECT1 and MAML2 genes is seen so frequently in mucoepidermoid carcinomas that it has been suggested as a diagnostic marker for that tumour (see Chap. 7). In PLGA, however, no such 11q21 rearrangements have been observed so far [17]. There are few cytogenetic studies of PLGA, but chromosome 12 abnormalities affecting both the q and p appear to be frequent [68]. Comparative genomic hybridisation has recently demonstrated a relative loss of material on chromosome 6q23-qter and 11q23-qter [46]. In fact, no recurrent genetic aberrations have so far been identified in PLGA. A recent study showed that the PLGA genome is stable and contains few copy number alterations. One out of nine cases of PLGA did however express the adenoid cystic carcinoma-associated MYB-NFIB gene fusion (see Chap. 8) [87].

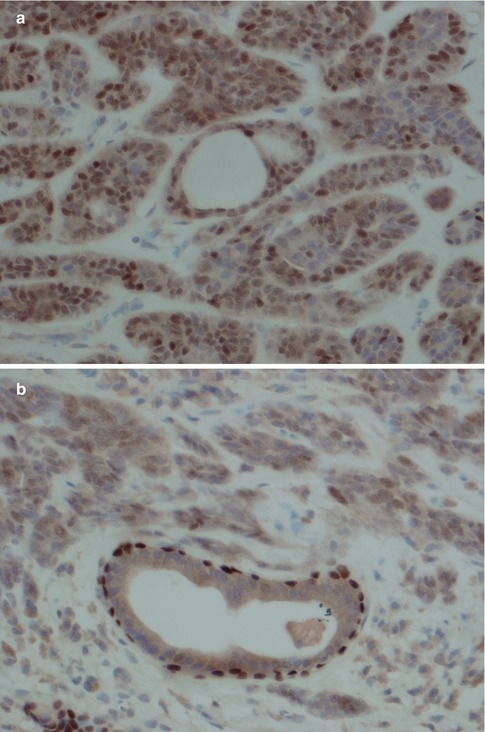

12.3.1 Cytokeratins, p63 and Nestin

The tumour cells of PLGA are immunoreactive for many different cytokeratins, e.g. low and high molecular weight cytokeratins (LMWK and HMWK, respectively), CK7, AE1/AE3, CK1 and CK8. Staining with low molecular weight cytokeratins is usually stronger than that of HMWK. PLGAs are variably positive for CK14, EMA and CEA, but often negative for cytokeratins 13 and 19 [86]. The demonstration of cytokeratin is hence of very limited diagnostic value as they are expressed in most epithelial salivary tumours. The luminal cells of PLGA exhibit ductal differentiation and strong staining for HMWK, but weak or negative for EMA and CEA, and only occasional positive staining for HMWK. The non-luminal cells show a phenotype in keeping with basal cell differentiation and possibly less commonly with myoepithelial cells, staining positive for both LMWK and HMWK [86]. The non-luminal cells are rather uniformly positive for p63 [27, 35, 90]. Nestin (an intermediate filament first identified in neural progenitor cells) is becoming a novel wide-spectrum abluminal cell marker in salivary neoplasms. Hence nestin was not detected in Warthin tumour, ACC, MEC or SDC, but in all PLGAs and most PAs [124].

12.3.2 Vimentin

Vimentin is like keratins expressed in a very high percentage of PLGAs [13], but contrary to keratins, vimentin is more occasionally or not at all expressed in some other salivary gland tumours, e.g. adenomas like canalicular adenoma [38]. Vimentin is however also expressed in both pleomorphic adenoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma which are the two main differential diagnoses to PLGA. A strong vimentin stain would favour PLGA (Fig. 12.8c).

12.3.3 S-100

Similarly, PLGAs are positive for S-100 in the vast majority of cases but so are other salivary gland tumours with participating neoplastic myoepithelial cells. It is noteworthy that in a number of studies every single case investigated has been positive for keratins (particularly LMWK), vimentin and S-100 (with the exception of one S-100-negative case of 39 cases in the study by Castle and associates) [4, 13, 43, 93, 102]. A significant co-expression of S-100 and mammaglobin is seen in 60 % of PLGAs but only in a minority of ADCCs [82].

12.3.4 Smooth Muscle Actin

12.3.5 Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is expressed by a number of cells in the central nervous system but also in some tumours not generally considered to be of glial origin. In this context, its presence has been demonstrated in a high percentage of particularly pleomorphic adenomas and to a much lesser degree in PLGA. In one study of 36 cases of pleomorphic adenoma, all 36 were positive whilst only 11 out of 42 PLGAs showed a faint patchy reactivity [20]. Contrary, in another study, all their seven cases of PLGA were reported to be negative for GFAP, whilst pleomorphic adenomas consistently were positive [4, 5]. This paucity or total absence of GFAP in PLGAs has been documented in other studies as well [43, 78, 93]. GFAP can thus often be a useful ancillary marker in distinguishing cases of PLGA from pleomorphic adenoma, especially in small palatal incisional biopsies where the histological features may be very similar.

12.3.6 Bcl-2, Galectin-3, Laminin and Collagen IV

PLGAs are reported to be immunoreactive to bcl-2 in a very high proportion of cases [13, 86] but so are many other salivary gland tumours as well, adenoid cystic and acinic cell carcinoma included. The intensity and extent of bcl-2 tend to be stronger in benign tumours compared to malignant salivary neoplasms and stronger in low-grade malignant neoplasms than in high-grade tumours, and its value as adjuvant marker in the differential diagnosis remains uncertain or very limited [48, 49, 55, 75, 77, 107]. Studies have shown PLGA (and adenoid cystic carcinoma) to be immunopositive for galectin-3, a nonintegrin β-galactosidase-binding lectin, implicated in a variety of biological events such as tumour cell adhesion and proliferation [24, 34, 84]. Similarly, both PLGAs and adenoid cystic carcinomas have shown immunoreactivity for extracellular matrix components like laminin and collagen IV [64]. The value of these three proteins as possible diagnostic and/or prognostic tools remains to be clarified.

12.3.7 Ki-67 and MCM-2

The use of proliferative cell marker Ki-67 can be helpful in distinguishing PLGA from adenoid cystic carcinoma. The initial study by Skálová and associates [104] demonstrated the proliferative rate in PLGA to be below 6.4 % (average 2.4 %) and considerably higher rate (average 21.4 %, range 11.3–56.7 %) in adenoid cystic carcinoma. These findings are in agreement with later studies [13, 99], but there are also other investigations indicating a somewhat higher proliferation rate for PLGA with an average of 7 % [86] and considerably lower proliferation rate in both PLGA in adenoid cystic carcinoma (average of 1.2 and 3.71 %, respectively) [10] or no major difference at all [61]. We still feel that Ki-67 staining still can be useful as an additional tool in the differential diagnosis between PLGA and PA on one hand versus adenoid cystic carcinoma. The diagnosis of PLGA will never depend on the Ki-67 index, but the labelling index can be rather supportive of one or the other of the two diagnoses, should the individual index be very low or very high. In practical terms, a very low labelling index would be that the proliferating cells constitute less than 5 % of cells and a very high index more than 15 %. The so-called minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins have recently been used as proliferation marker. There are six minichromosome maintenance proteins (MCM-2 to MCM-7) which are essential for the initiation and elongation of DNA replication. Vargas and associates showed the labelling index for MCM-2 to be higher than that of Ki-67 and can hence be useful in distinguishing between PLGA and adenoid cystic carcinoma [116]. The superior sensitivity of the MCM proteins over, e.g. Ki-67 as proliferation marker resides in the fact that MCMs also identify non-cycling cells with proliferative potential, as well as cycling cells [109]. It thus appears as MCM-2 may serve as a novel and better biomarker for diagnostic and prognostic purposes but has hitherto not gained any important impact in routine surgical pathology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree