Overview

Air pollution continues to be a major threat to health in both developed and developing countries

Long-term exposure to fine particles shortens life expectancy: the effect is a result of an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease

Indoor air pollution in developing countries is now recognised as a very serious public health problem

Some of the effects on health of the ambient aerosol might be explained by very small particles but this is, as yet, uncertain.

Pollution of the air, soil and water is a major problem in many parts of the world. In developed countries the worst excesses of industrial pollution are coming under control but have been replaced by pollutants generated by motor vehicles. In developing countries the rapid increase in industrialization combined with the increased use of motor vehicles is producing conditions as bad, if not worse, than those seen in developed countries a century ago. Dense chemical smog is common in megacities such as Mexico City and So Paulo and is an increasing problem in many of the cities of China and India.

Photochemical air pollution is a problem in the Mediterranean area; in fact, only the dense and damp smogs so characteristic of London until the late 1950s seem to have disappeared (Figure 21.1). The combination of a damp, foggy climate and intensive use of soft coal in inefficient household fireplaces does not seem to have been repeated on such a scale elsewhere, although similar conditions may have occurred in Eastern European countries and in Istanbul. High concentrations of coal smoke and sulphur dioxide do occur in some Chinese cities, and forest fires have, over recent years, caused significant ‘haze’ conditions in South East Asia.

Air pollution is not solely an outdoor problem: in many countries indoor pollution produced by the use of biomass as a fuel damages health, especially that of women and young children who may be exposed for much of a 24-hour day. The seemingly inevitable link between poverty and poor environmental conditions persists, and efforts to resolve this and instil a sense of environmental justice are only now beginning. (see also Chapter 22).

Air pollution is a major problem, but so is pollution of water. Attention has been drawn to the contamination of drinking water with arsenic leached from soil in West Bengal. High levels of lead, nitrates and pesticides have also been detected in drinking water in various countries. A problem in California has been the seepage of methyl tert butyl ether (MTBE) into drinking water: an ironic problem as MTBE was added to petrol as an oxygenating agent designed to reduce the production of air pollutants. In October 2010, the collapse of a storage reservoir for waste produced by an aluminium refinery in Hungary led to widespread contamination of the Danube. Local residents were exposed to deep red slurry: iron oxide accounted for the colour. Concerns about heavy metals reaching the food chain were expressed widely.

Air Pollution

Air pollution is a worldwide problem. Concentrations in cities in developing countries often exceed the WHO Air Quality Guidelines by a wide margin (WHO 2005). The impact of air pollution on health is large: some 3 million deaths each year are attributed by the WHO to air pollution. Of these, 2.8 million result from indoor exposure (1.9 million occurring in developing countries) and only 0.2 million occur as a result of outdoor exposure. It is salutary to consider how much effort is put into controlling outdoor concentrations of air pollutants compared with indoor concentrations (Figure 21.2).

Particulate Air Pollution

Until about 1990 it was believed that ambient concentrations of particles in countries like the United Kingdom had fallen to such levels that effects on health had essentially disappeared. This is now known to be untrue.

An increase in the daily average concentration of particles monitored as PM10 (the mass of particles of, generally, less than 10 μm diameter per cubic metre of air) of 10 μg/m3 is associated with about a 0.7% increase in non-accidental, daily deaths. The effect on hospital admissions is of the same order. Even in a small country like the United Kingdom, this leads to a large impact on health: 8100 deaths brought forward (all causes) and 10 500 hospital admissions (respiratory) either advanced in time (i.e. the admissions would have occurred but occur earlier as a result of exposure to pollution) or caused de novo.

It has been argued that the extra deaths calculated in this way are merely deaths advanced by just a few days in those who are already seriously ill: an example of a so-called ‘harvesting effect’. This does not seem to be true: recent work by Schwartz has suggested that at least some of the deaths may be advanced by months. Studies in the United States have shown that living in a city with a comparatively high level of particles leads to a reduction in life expectancy. The effect is significantly larger than that of daily variations in concentrations of particles: an increment of 10 μg/m3 in the long-term average concentration of particles monitored as PM2.5 (the mass of particles of, generally, less than 2.5 μm diameter per cubic metre of air) is associated with a 6% increase in non-accidental all-cause mortality at all adult ages. The effect seems to be mainly on deaths from cardiovascular disease.

Calculating the extent of the impact at an individual level is impossible because we do not know how many in a population are affected. If all people were affected equally, then at levels of particles found in the United Kingdom, the individual impact would be of the order of a 6-month loss of life expectancy. This effect can be represented by the number of premature deaths occurring each year due to long-term exposure to current levels of fine particles. The effect, expressed in this way, is large: more than 30 000 premature deaths per year in the UK. Whether expressing the effect in these terms is informative, though arithmetically accurate, is open to debate. It is very unlikely that all these deaths can be attributed solely to the effects of exposure to particles; it is more likely that exposure increases the risk of death in a large number of people in whom other contributing causes play a large, and perhaps more important, role.

If this is the case in the relatively unpolluted United Kingdom then the effect in much more polluted developing countries must be large indeed. Predicting the size of the effect in developing countries is not easy as it will, in part, depend on the background prevalence of disease. If the effect of exposure is to increase the rate of development of disease, then as the background level of cardiovascular disease rises so will the impact of particles.

These calculations of the impact of particles on health have produced a revolution in thinking in inhalation toxicology.

Some, being unable to understand the mechanism of effect of ambient particles, have argued that the reported associations are not causal. Others, rather more usefully, have set out to find the mechanisms of action of ambient particles and research has flourished.

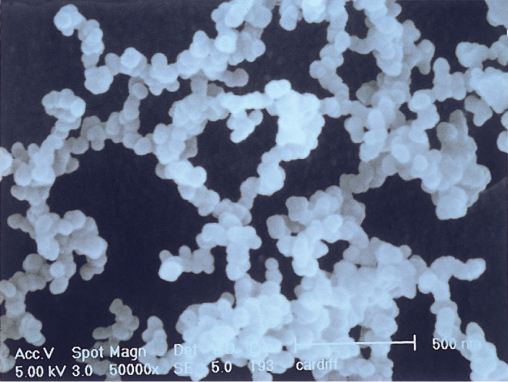

Ultrafine particles (less than 100 nm in diameter) have been suggested to play an important role (Figure 21.3). These particles contribute little to the mass concentration of the ambient aerosol but a great deal to its number concentration. The idea that the number of particles in every cubic metre of air may be more important than the mass per cubic metre has gained ground since it was suggested in 1995. More recently, the idea that total particle surface area per unit volume of air may be important has been suggested. If this is true then air quality standards, currently defined in terms of mass concentrations, will need revision (Box 21.1).

Figure 21.3 Electron micrograph of diesel particles. Individual particles are about 25 nm in diameter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree