and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

3.1 Definition, Site and Incidence

Since its first description by Billroth in 1859, the terminology for this entity has veered to and fro between ‘mixed tumour’, complex adenoma and pleomorphic adenoma. Although the tumour often has a prominent mesenchyme-appearing ‘stromal’ component, it is not truly a mixed neoplasm derived from more than one germ layer; it is of purely epithelial origin. The importance of pleomorphic adenoma (PA) lies primarily in the fact that it is by far the most common salivary gland neoplasm and that it may recur. However, it is also important to recall that malignancy develops in at least 5–10 % of cases, hence making carcinoma in pleomorphic adenoma the fourth most common malignant salivary gland tumour. In a compilation of 60 individual studies, Gnepp reported that the average rate of malignant change was 6.2 % of all pleomorphic adenomas (range 1.9–23.3 %) and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma represents approximately 12 % of all malignant salivary gland neoplasms [40] (see Chap. 10). Its bad reputation for recurrence was obtained from decades of surgical enucleating procedures, but since superficial parotidectomy has been more widely applied, the recurrence rate has greatly improved. The term pleomorphic adenoma defines its benign, entirely epithelial origin, at the same time emphasising its variable histological appearance. The histological pleomorphism is both architectural and cellular, but the term pleomorphism does not imply atypical cells but instead pleomorphic, irregular cells of different histological appearances. The old WHO classification is still valid in defining pleomorphic adenoma as ‘a tumour of pleomorphic structure containing luminal-type ductal epithelial cells, myoepithelial cells and tissue of mucoid, myxoid or chondroid appearance’ [98, 103].

The majority of PAs, about 80 %, are situated in the parotid gland, particularly in its tail and inferior parts. Of the remaining 20 %, approximately half are located in the submandibular gland and half in the minor salivary glands of the upper respiratory tract. The palate is the most common site for pleomorphic adenomas of the minor salivary glands, accounting for approximately 60 % of intraoral examples. This is followed by lip (20 %) and buccal mucosa (10 %) [61, 81]. A sublingual origin is very rare but does occur in 0.3–1 % of cases [20]. Intraosseous PA is exceedingly rare with only some ten reported cases [7, 138]. Malignant intragnathic salivary neoplasms are considerably more common although still rare and mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the predominant type. A few cases of pleomorphic adenomas in the external ear canal have been reported. These are thought to arise from the ceruminous glands and/or from the ectopic salivary tissue [8, 13, 76, 119]. Occasionally PA may be found in ectopic salivary gland tissue in the neck, often in the lymph nodes, but also in the thyroid isthmus [68, 72, 123] (see also Sect. 1.4). Pleomorphic adenomas may also be encountered outside the aerodigestive tract, for example, in the lacrimal gland, breast, vulva and sella turcica [26, 113, 114] and also possibly in the kidney [85]. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common salivary gland neoplasm in adults, irrespective of the site with the exception of the sublingual gland, and accounts for approximately 60–70 % of all salivary gland neoplasms. It is also by far the most common epithelial salivary gland tumour in children [30, 37, 46, 109].

The relative frequency of individual salivary gland tumours is very difficult to estimate with accuracy (see also Chap. 7). This is due to that available data derive from numerous different settings, some studies include minor salivary gland tumours only, many series are relatively small, and there are also real differences between different parts of the world. All figures given below, and in other parts of this book as well, shall hence be interpreted with caution. In a compilation of some of the major series of salivary gland tumours in the literature, pleomorphic adenoma is found to comprise about 70 % of all parotid tumours, about 50 % of those in the submandibular gland and 40 % of salivary tumours in the oral cavity [80]. Pleomorphic adenoma occurs at any age but is most common in adults between the ages 30 and 50, and there is a slight female predilection. The annual incidence is 2.4–3.05 per 100,000 population [31]. In a large and thorough study from one institution, Jones and associates [57] describe the range and demographics of 741 major and minor salivary gland tumours in a UK population. In their study, PA was the most common tumour accounted for 68.4 % of benign tumours and 44.4 % of all salivary tumours. Similar figures were reported in one of the largest retrospective studies comprising 6,982 salivary gland neoplasms in an eastern Chinese region. Pleomorphic adenoma represented 69 % of tumours of all tumours, and 80 % of PAs were located in the major salivary glands [120].

3.2 Clinical Features and Gross Appearances

Pleomorphic adenomas are generally slowly growing tumours often present for years before the patients seek medical advice. The most common clinical presentation is that of a painless, slowly growing, parotid mass, which is firm and mobile. Facial nerve palsy and pain are rare. Approximately 10 % of parotid tumours present in the deep portion of the gland beneath the facial nerve and may present as a parapharyngeal mass. Palatal tumours are frequently found at the junction of the soft and hard palate, and when located in the hard palate, they are appreciated as fixed rather than mobile due to proximity of the underlying mucoperiosteum. Similarly, recurrent parotid tumours are often fixed to the underlying tissues. Pleomorphic adenomas vary in size usually being 2–6 cm in diameter in the major salivary glands, whilst they are much smaller in the minor salivary glands. There are also some huge ones on record and referred to as giant pleomorphic adenoma. Most giant PAs have been reported in the parotid gland (85 %), but a giant submandibular PA has been reported, for example, a 2.2 kg [45] and one measuring 16 × 15 × 12 cm [89]. Schultz-Coulon made a literature review of the 140 years before 1989 and found 31 cases of giant PAs. The weight of the tumours varied from 1 to 26.5 kg [96].

Pleomorphic adenomas are usually solitary although may be synchronous or metachronous with other tumours, usually Warthin tumour but also mucoepidermoid carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma, but also a case synchronous with a mandibular keratocystic odontogenic tumour has been reported [3, 88, 99]. Recently, Southorn and associates reported metachronous PAs (6 months), one occurring in the parotid and the other in a minor salivary gland in a 32-year-old patient [108]. Pleomorphic adenoma is a circumscribed and encapsulated, often lobulated tumour with a fibrous capsule of varying thickness. On gross examination of a superficial parotidectomy specimen, part of the PA often tends to bulge out from the parotid tissue only being surrounded by a thin capsule. On microscopic examination, this may be misinterpreted as incomplete excision which emphasises the need that both macroscopical and microscopic examination is done by the same reporting pathologist. The cut surface is usually homogeneous and whitish, but with increasing amount of cartilaginous material, it may be glistening. Haemorrhage and necrosis may be present but are not frequent findings.

3.3 Histopathology

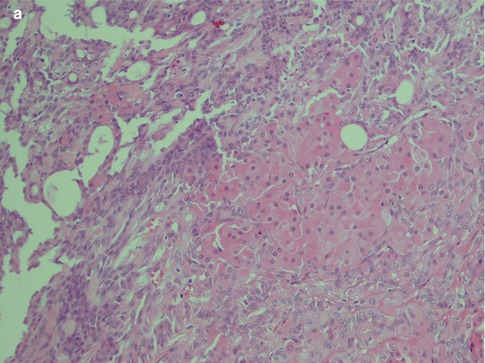

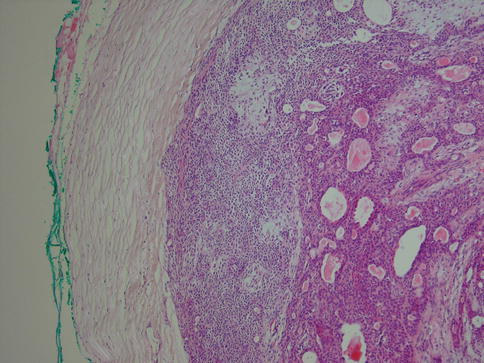

Pleomorphic adenoma is of purely epithelial origin with ductal and the pluripotent myoepithelial cells, and its mesenchymal stroma, being the neoplastic components. All cell types proliferate. Pleomorphic adenoma thus consists of a mixture of myoepithelial cells and ductal cells within a mesenchymal background. The cells of mesenchymal histological appearance are partly stromal cells, partly metaplastic myoepithelial cells. On rare occasions, sebaceous and mucinous and serous acinar cells can be seen [21, 29]. When acinar cells are present, they are often found towards the periphery of the tumour and likely represent residual acinar structures entrapped in the tumour (Fig. 3.1). A substantial proportion of stromal cells in pleomorphic adenomas have also been identified as dendritic cells of the interdigitating variety. The capsule of pleomorphic adenoma consists of fibrous tissue of varying thickness (Fig. 3.2). The capsule may be poorly developed and partly absent and particularly so in minor salivary gland tumours and in tumours that are predominantly mucoid/myxoid. The partial lack of capsule in a particular histological section of the tumour and infiltration of neoplastic cells into an existing capsule are normal findings and should hence not be confused with malignancy arising in a pleomorphic adenoma (Fig. 3.3). The partial lack of a capsule is a feature that pleomorphic adenoma shares with myoepithelioma. Pleomorphic adenoma is seldom truly multifocal, and the multifocal appearance frequently observed by the pathologist is on many occasions artefactual and produced by cutting across fingerlike protrusions of a nodular tumour (Fig. 3.4).

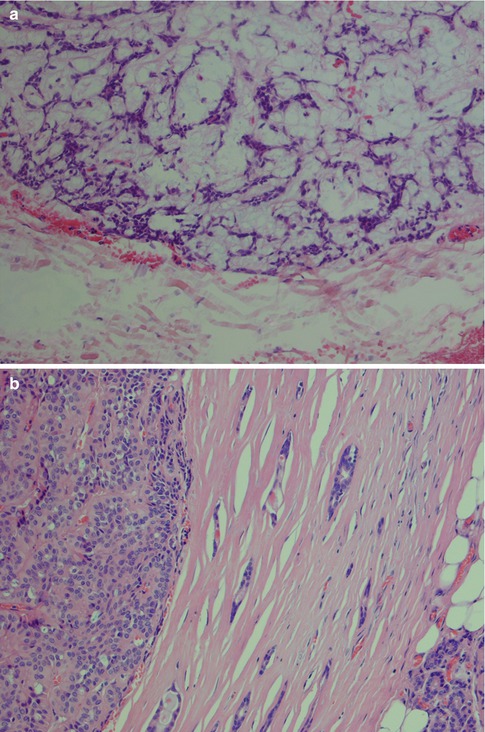

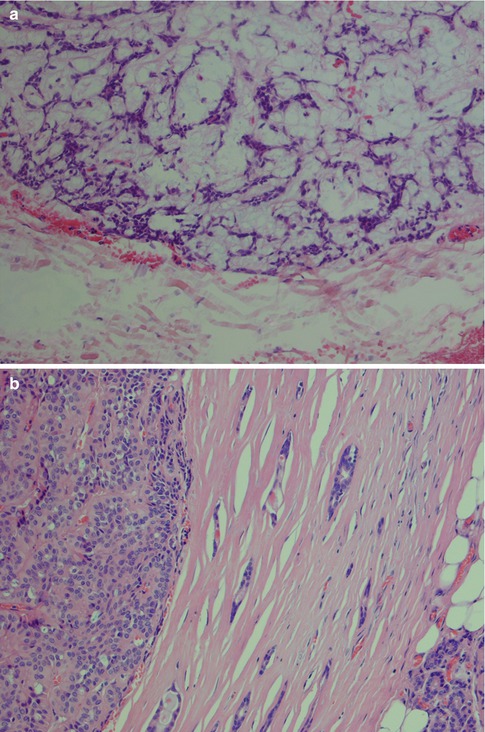

Fig. 3.1

Pleomorphic adenoma with a few groups of acinar cells (left)

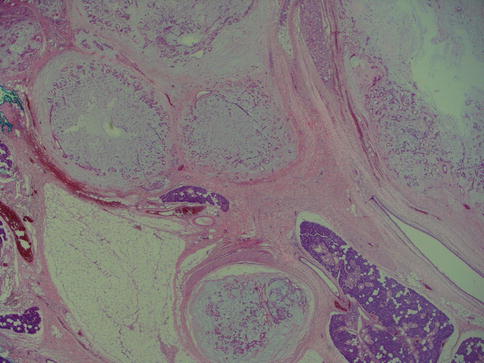

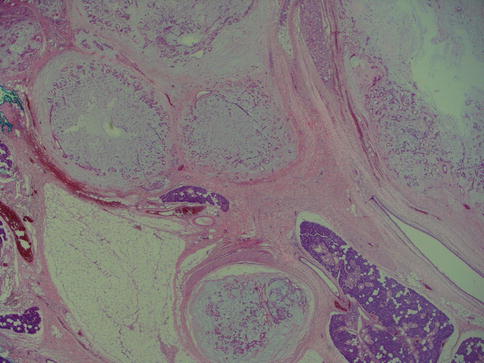

Fig. 3.2

Pleomorphic adenoma with a rather thick fibrous capsule

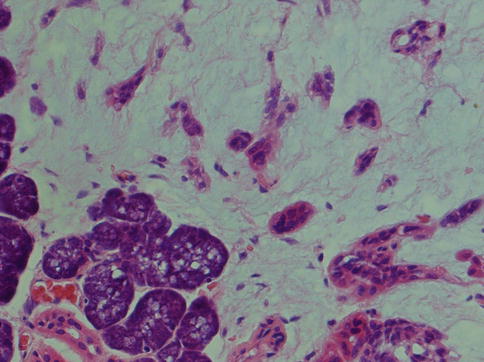

Fig. 3.3

(a) A parotid PA that in areas is lacking capsule. (b) Capsule violation

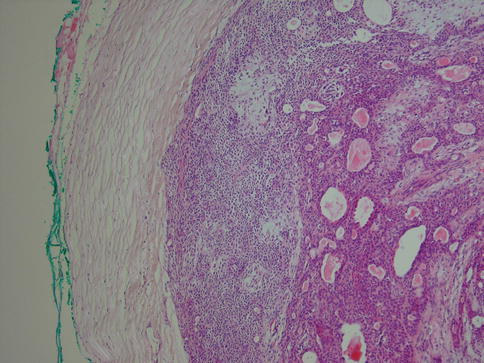

Fig. 3.4

Three small nodules (left) that are seen outside the main bulk of the tumour (right)

The neoplastic myoepithelial cells show a variety of morphologies including stellate or myxoid, spindle-shaped or myoid, epithelioid, plasmacytoid or hyalin, and clear (see Chap. 1, Fig. 1.3). Most of the neoplastic myoepithelial cells hence have a modified morphology different from the typical flattened or stellate form seen surrounding normal acini and intercalated ducts. Their immunoprofile also modifies. The ductal epithelial cells are often cuboidal and form duct-like structures, interlacing fascicles and sheets. The duct structures consist of inner ductal epithelial cells with or without surrounding layers of abluminal myoepithelial cells. The myoepithelial outer cells of the duct structures may be spindle-shaped, epithelial or clear cell in appearance (Fig. 3.5). This is a feature not only of pleomorphic adenoma but also of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas and some adenoid cystic carcinomas. The stroma is primarily mucoid/myxoid and chondroid but may also be fibrous and hyalinised, or hypocellular and richly vascularised. Long-standing tumours may show increased hyalinisation of the stroma. The chondroid stroma component appears to be true cartilage and is positive for type II collagen and keratin sulphate. The myoepithelial cells around the chondroid component express bone morphogenetic protein [BMP], whilst the ductal cells as well as the chondroid lacunar cells express BMP-6 [51, 62]. Most pleomorphic adenomas have areas showing different types of stroma, and only rarely will one see one sole type. The epithelial cellularity varies considerably between tumours but also within a tumour. An equal amount of cellular and stromal tissue is found in about one-third of neoplasms, and one-third are predominantly ‘stromal’ and one-third predominantly cellular. Within the hypercellular group, there are some that are very cellular, constituting approximately 10 % of all pleomorphic adenomas. The cellular variants are more often seen in minor salivary gland pleomorphic adenomas. There is no known correlation between cellularity and recurrence, neither to development of malignancy. The mucoid/myxoid variant of mesenchymal stroma is the most common followed by chondroid stroma. In some mucoid/myxoid forms of pleomorphic adenoma, the tumour cells are separated by a loose, oedematous, almost avascular stroma. This stroma may also be arranged in small or larger nodules that usually are poorly delineated. The nodules of myxoid stroma may however sometimes be rather well circumscribed which is rarely seen with chondroid nodules. A transition zone between myoepithelial cells and the mesenchymal-like tissue is usually present, suggesting a metaplasia of the former (Fig. 3.6). In cases with a mucoid/myxoid stroma with typical stellate and epithelioid myoepithelial cells, both the ductal-like and myoepithelial cells stain positively for p63. Both cell types show a distinct nuclear staining but also a moderate cytoplasmic staining. Similarly, in this myxoid/mucoid variant, both cellular elements are positive for vimentin and S-100, whilst pancytokeratin, SMA and SMM usually stain ductal cells and many but not all of the myoepithelial cells are negative. Other keratin markers like pancytokeratin, CK5/6, CK14 and CK8/18 similarly give a strong staining of the ductal cells but may also stain the myoepithelial cells, although weaker [23]. Further, in this setting, both cellular components tend to be negative for CD10. The most reliable markers for both types of cellular elements in this type of pleomorphic adenoma are hence p63, CK5/6, CK8/18, vimentin and S-100 (Fig. 3.7). It may be emphasised again that p63 and p73 genes are members of the p53 family and contrary to p53 play important roles in stem cell identity and cellular differentiation. Both are expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells, but it appears that p63 is a more specific marker of myoepithelial differentiation than p73 [97]. All isoforms of p63 are said to be expressed in normal salivary tissue, whereas pleomorphic adenomas (as well as myoepitheliomas and basal cell adenomas) dominantly express the transactivation-incompetent truncated isoforms [128]. On the other hand, studies have indicated that in normal salivary gland tissue, the two main isoforms are present, whereas the spliced variant DeltaNp73L is absent. The latter is however present in several tumours with myoepithelial/basal cell participation indicating its possible involvement in the neoplastic transformation [34]. A recent study indicates that nestin (an intermediate filament first identified in neural progenitor cells) may be a useful and reliable marker of abluminal cells in salivary tumours like PA, basal cell adenoma and epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma [135].

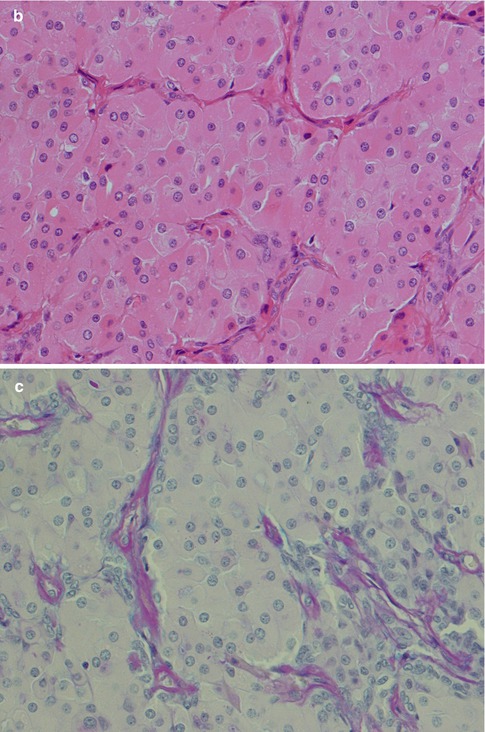

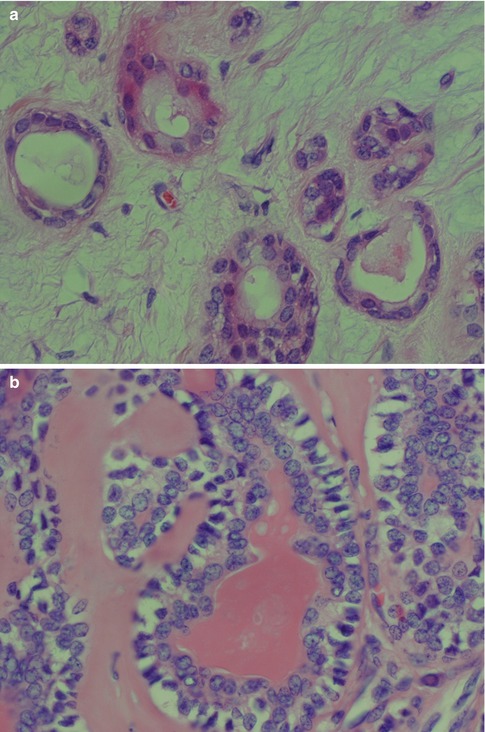

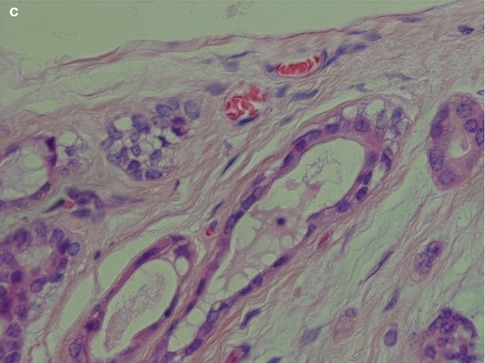

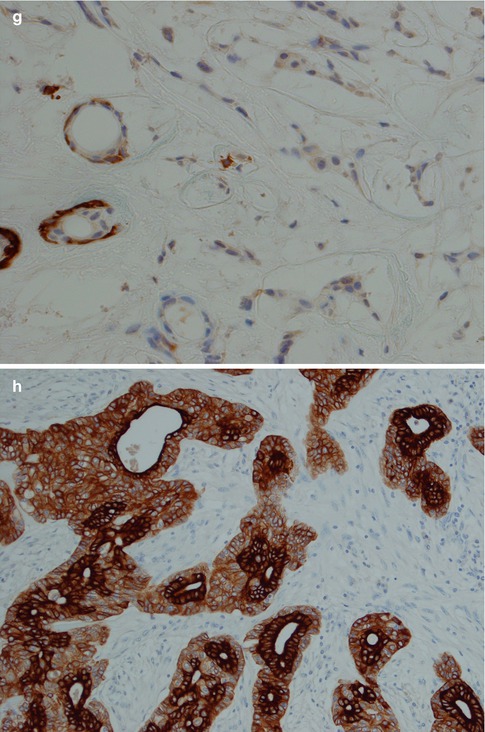

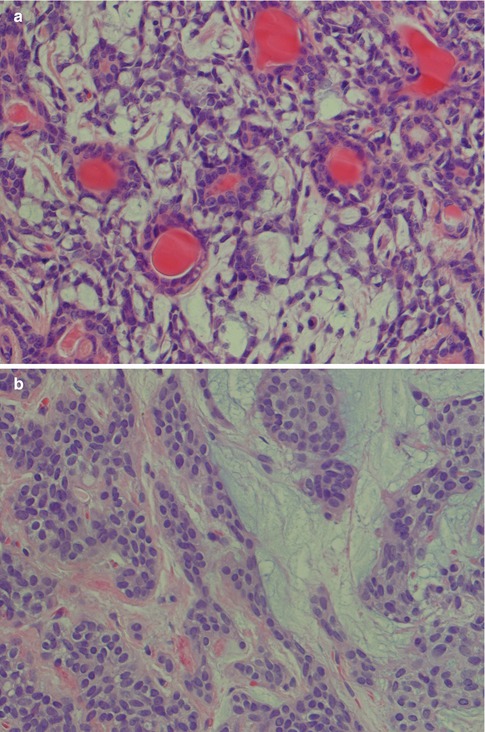

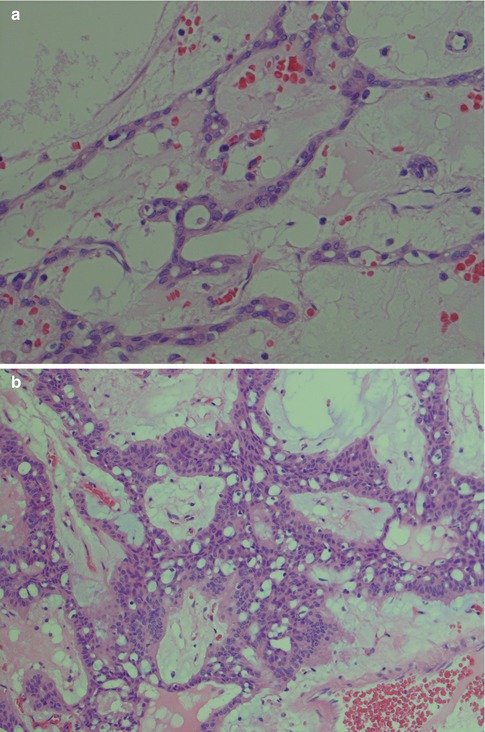

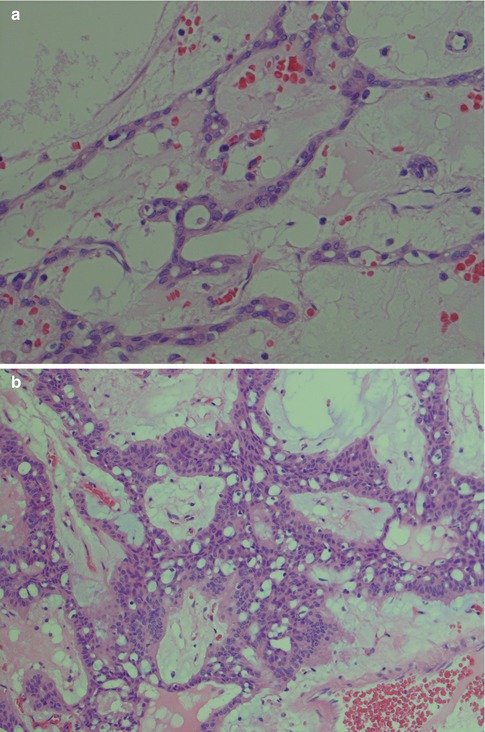

Fig. 3.5

(a) Ductal structures lined with flattened, cuboidal epithelium without any prominent layer of outer clear myoepithelial cells. (b) Ductal structure with inner, eosinophilic cells and outer clear myoepithelial cells. (c) Small ducts lined with partly flattened epithelial cells surrounded by clear myoepithelial cells. Top right a small duct without any visibly myoepithelial cells

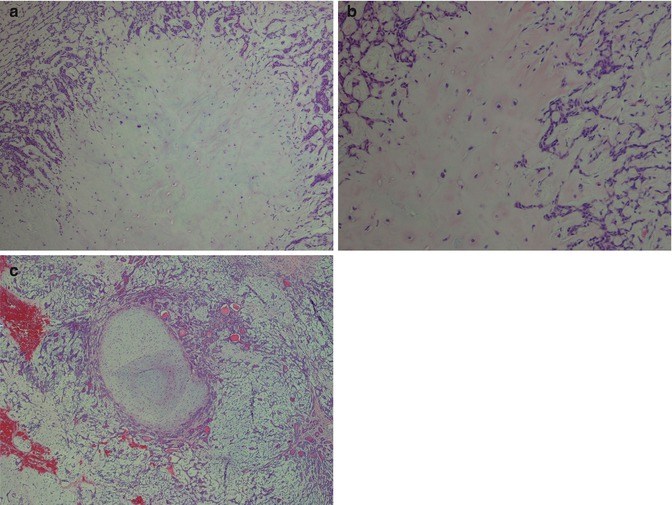

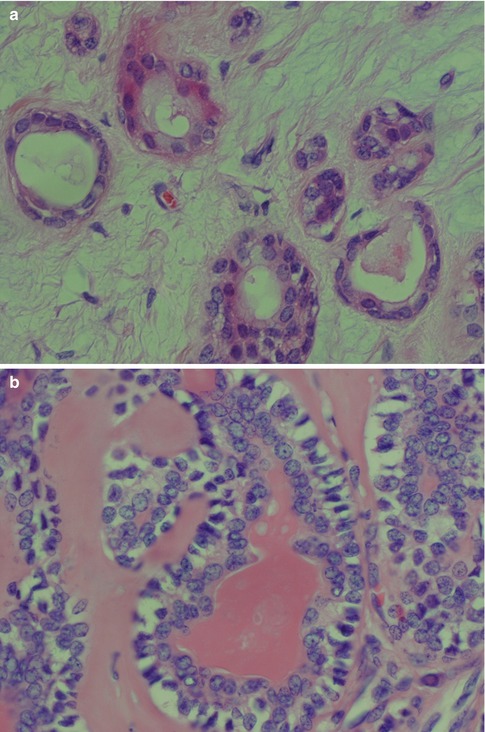

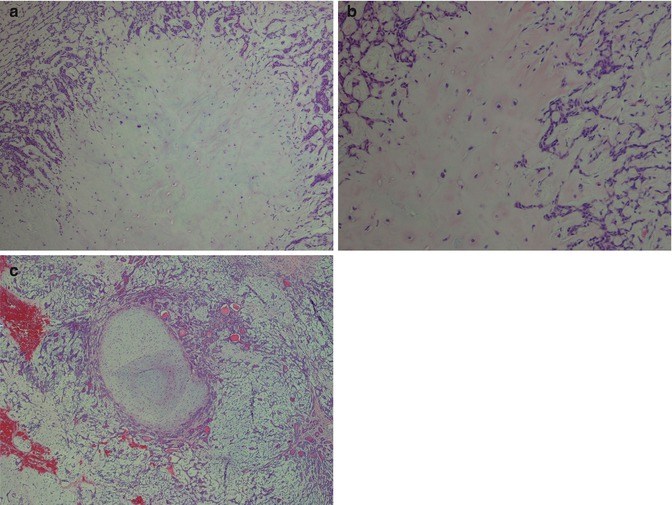

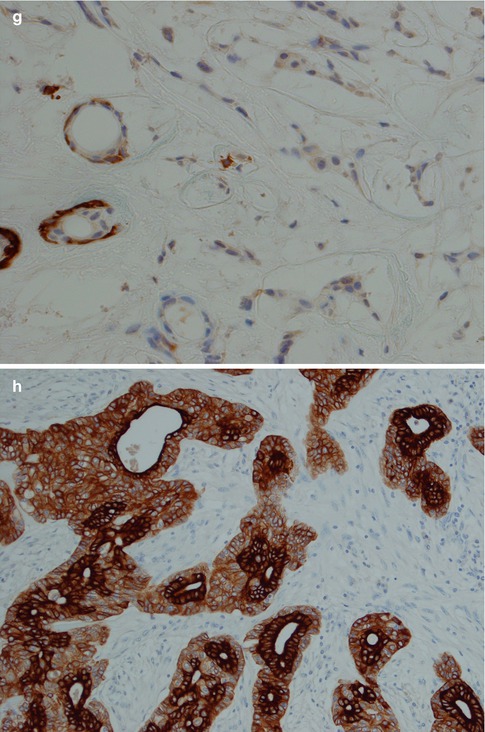

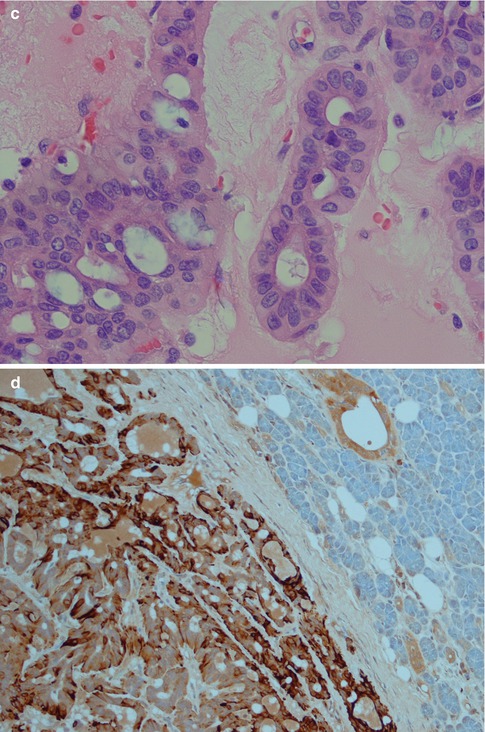

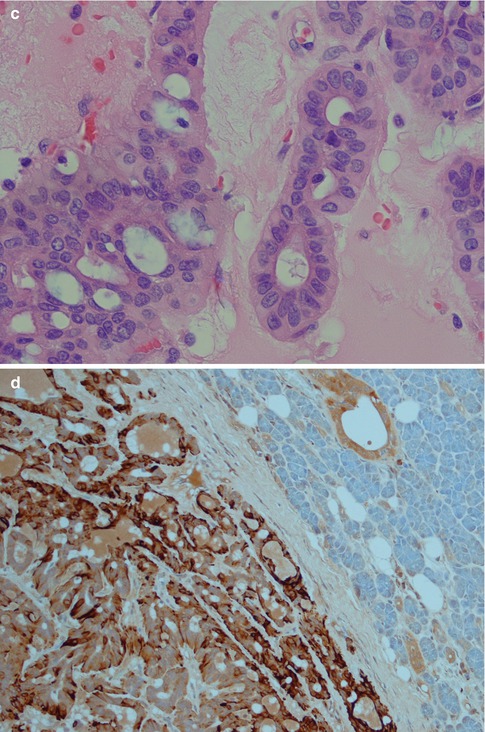

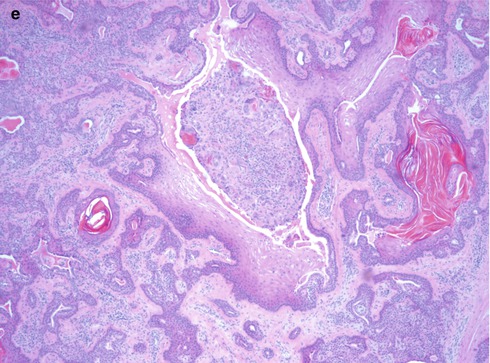

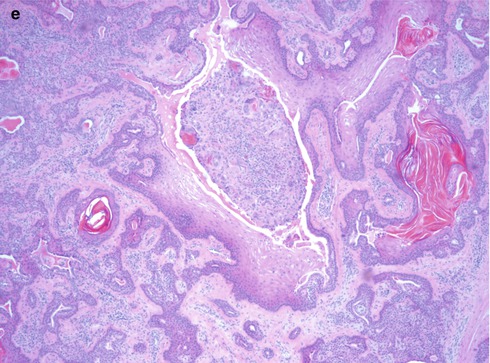

Fig. 3.6

(a) Myxoid stroma diffusively delineated from the more cellular area. (b) Chondroid stroma which appears to merge with the myoepithelial cells. (c) A rather well-delineated, almost circumscribed nodule of myxoid stroma. (d) Myoepithelial and ductal cells in a hyalinised, fibrous stroma. (e) Typical stellate myoepithelial cells in a mucoid/myxoid stroma

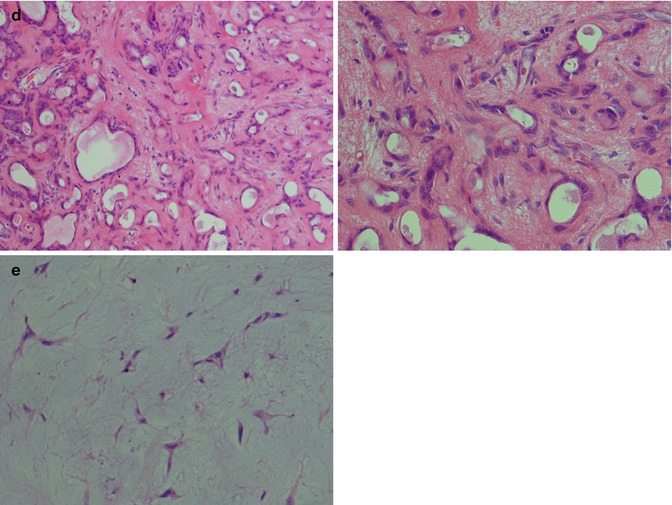

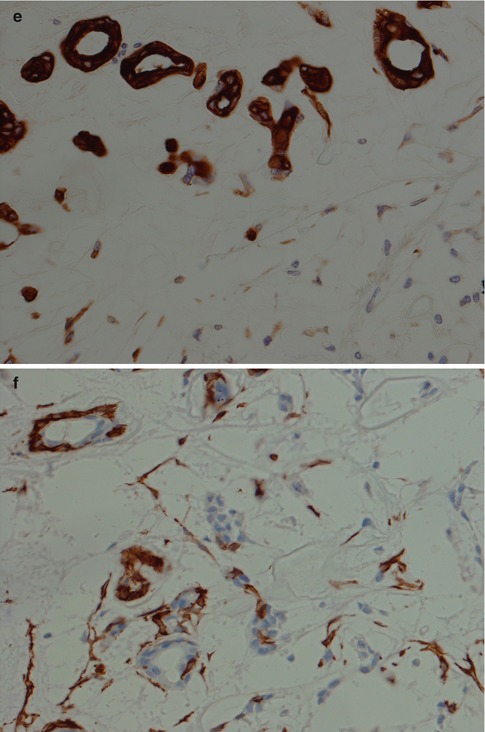

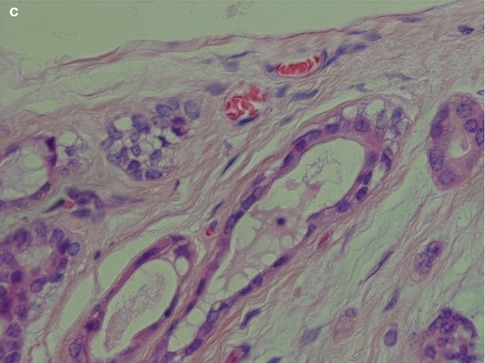

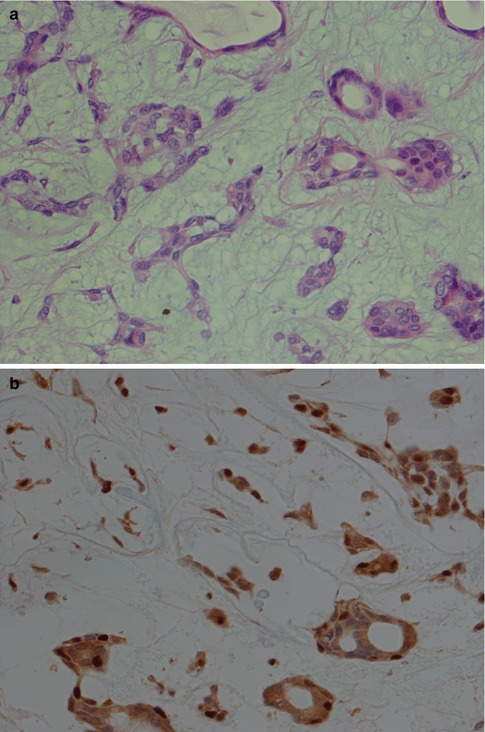

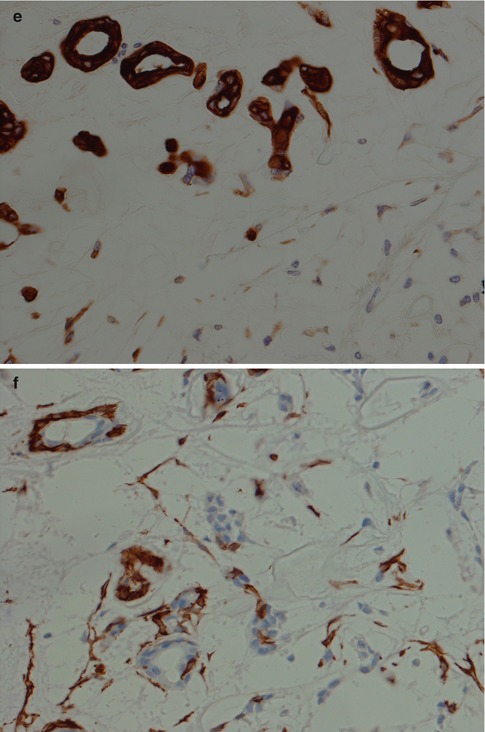

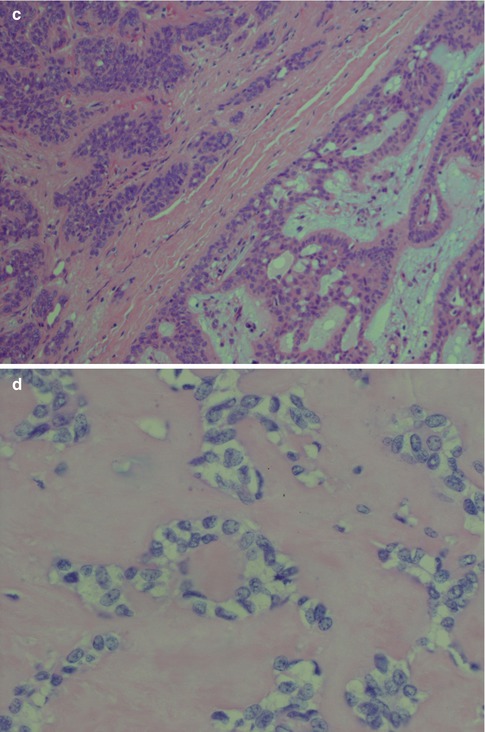

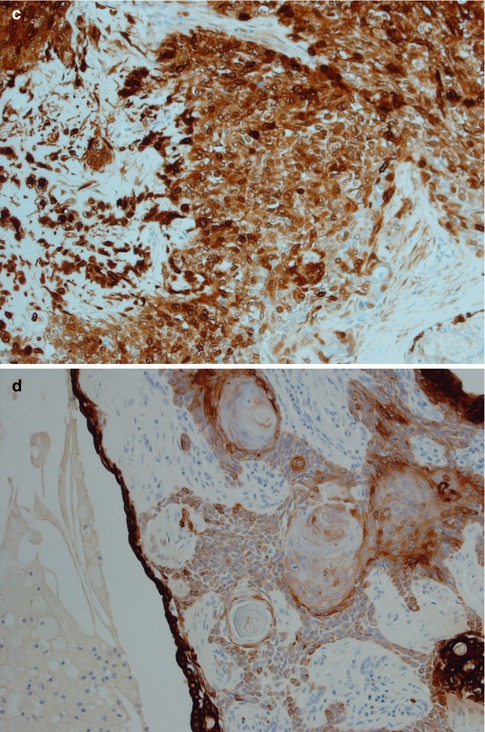

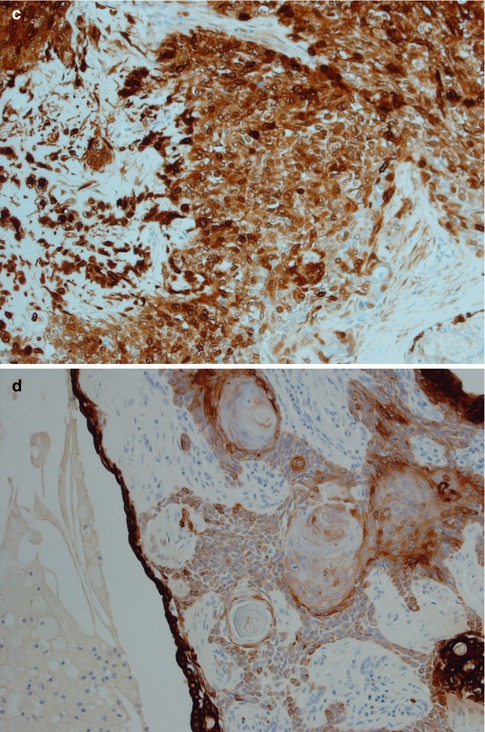

Fig. 3.7

(a) PA with ductal and myoepithelial cells in a myxoid stroma. (b) p63 immunostaining with positive nuclear staining of both ductal and myoepithelial cells. (c) Both ductal and myoepithelial cells positive for vimentin. (d) Similar staining with S-100. (e) Ductal cells positive but several myoepithelial cells are negative for pancytokeratin. (f) SMA-positive cells around most ducts but stellate myoepithelial cells in stroma mainly negative. (g) SMM shows a similar pattern to SMA. (h) CK8/18 stain with strongly positive ductal cells but also a moderate staining of myoepithelial cells

During the recent years, much increased knowledge has been obtained about the pleomorphic adenoma gene 1, PLAG1. This is a zinc finger transcription factor gene and is the target gene and consistently rearranged and overexpressed in pleomorphic adenomas with 8q12 abnormalities, often t(3;8)(p21;q12) translocations (see below, Sect. 3.6). For example, one study showed tumour cells in all 45 cases of PA tested to be immunopositive for PLAG1, irrespective of PLAG1 rearrangements. There was a limited expression in glandular cells but almost invariably positive in myoepithelial and cartilaginous parts of the tumours. The same study also included 46 non-pleomorphic adenoma neoplasms, 39 of which were negative [78]. These findings make immunohistochemical investigation with PLAG1 very useful. PLAG1 is of course not a stand-alone discriminatory staining for PA, but a PLAG1 immunonegative staining will constitute a rather strong support that salivary tumour is not a pleomorphic adenoma.

Pleomorphic adenomas show a vast number of different microscopic patterns depending on the arrangement of the epithelial cells and how much and what type of stroma is present. The relative proportion of ductal cells and myoepithelial cells varies from case to case and within the same tumour. The ducts may have very few surrounding myoepithelial cells and be seen lying free in a hypocellular stroma. The ductal cells tend to be eosinophilic and cuboidal, but often somewhat flattened. The ducts are usually small but may be distended to form microcysts. They often contain clear fluid but also a PAS-positive, eosinophilic secretory material. In other areas, the inner duct-lining cells and outer myoepithelial cells are clearly visible (Fig. 3.5b). The outer myoepithelial cells often tend to form sheets of cells around the ducts and gradually merge into the stromal component. In other areas, the surrounding myoepithelial cells are not clear cell in type but are small, flattened and dark, sometimes spindle-shaped. In many tumours, one will find areas with numerous ducts without prominent surrounding myoepithelial cells that are instead forming a kind of network of cords and strands in a rather loose stroma. The myoepithelial cells in these tumours are stellate and spindle-shaped in form and rarely clear cell or plasmacytoid in type. In yet other tumours, there are prominent solid sheets of myoepithelial cells that are epithelial and plasmacytoid in appearance. The epithelioid and the plasmacytoid type of myoepithelial cells are often placed in a bluish, slightly myxoid stroma but may also be found in fibrous and hyalinised stroma (Fig. 3.8). In some pleomorphic adenomas, there are areas with proliferating cells that have a reticular (canalicular-like) form and may mimic a canalicular adenoma. The histological appearance is somewhat monotonous with interlacing fascicles or cords of epithelial cells in a hypocellular mucoid, richly vascularised stroma. In these cases, the typical areas of chondroid or myxoid stroma can be difficult to find. The fascicles are usually composed of ductal cells forming small tubules and of spindle-shaped and epithelioid myoepithelial cells. The predominant epithelial cell may however be spindle-shaped myoepithelial cells with only few ductal cells present, the former sometimes having a basaloid appearance and may hence mimic a basal cell adenoma. In these cases, the myoepithelial immunophenotype and lack of one of the four typical morphological patterns seen in basal cell adenoma will help to distinguish pleomorphic adenoma. In other cases, the proportion of ductal cells in the interlacing fascicles is more prominent. There are true ductal structures but also numerous non-glandular spaces like ‘punched out’ holes similar to those seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Such pleomorphic adenomas consist primarily of epithelial ductal cells with a limited amount of myoepithelial cells. The latter are more epithelioid in type rather than spindle or plasmacytoid which is reflected in their immunoreactivity. They are positive for different keratins, S-100 and vimentin whilst mainly negative for SMA and MSA and only scattered positivity for p63 (Fig. 3.9). Tumours with numerous myoepithelial cells of plasmacytoid type are more commonly found in pleomorphic adenomas (and myoepitheliomas) of the minor salivary glands. The plasmacytoid tumours tend to be positive for vimentin, cytokeratin, S-100 and GFAP whilst negative for SMA and MSA. This is in contrast to tumours with predominantly spindle-shaped myoepithelial cells which tend to be positive for SMA and MSA, in addition to sharing the positivity for the other four markers. The staining patterns for SMA and MSA are in keeping with the absence of myogenous differentiation in the plasmacytoid cells [35].

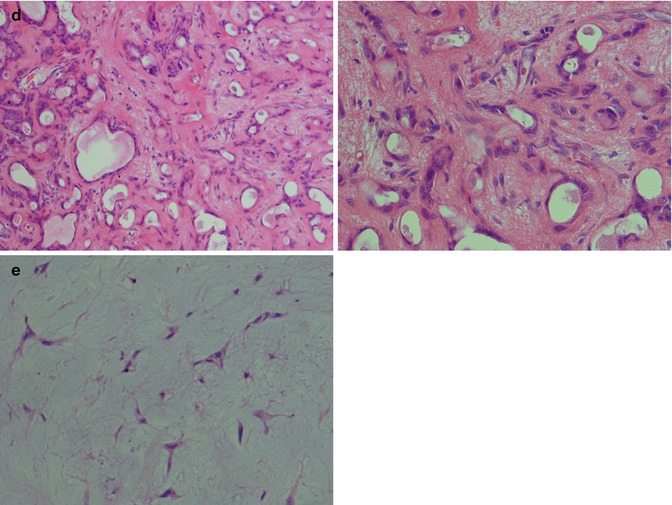

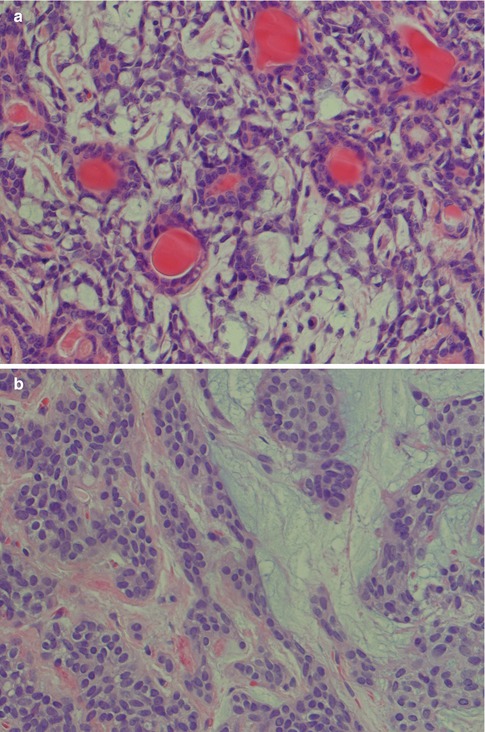

Fig. 3.8

(a) PA with numerous ducts without prominent surrounding myoepithelial cells. (b) Predominance of epithelioid myoepithelial cells in a myxoid stroma (right) and in a fibrous, partly hyalinised stroma (left). (c) Epithelioid and spindle-shaped myoepithelial cells in a partly hyalinised stroma (left) and eosinophilic ductal cells in a mucoid/myxoid stroma (right). This hyalinisation is not extensive and contains too many cellular elements to be regarded as an atypical feature. (d) Clear myoepithelial cells in a hyalinised stroma

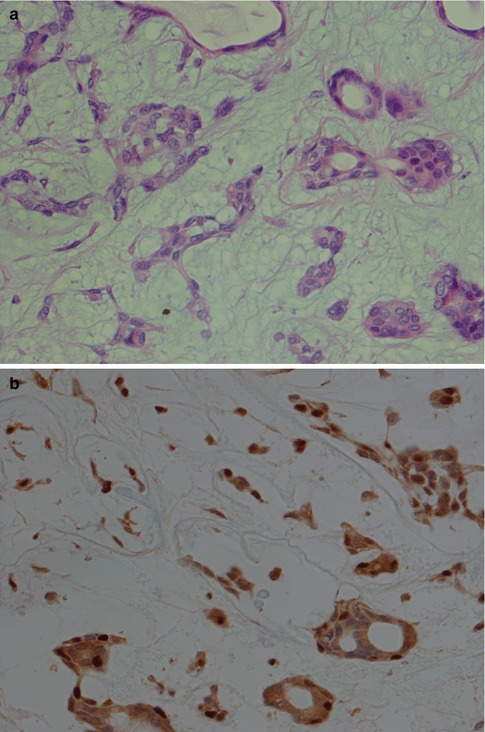

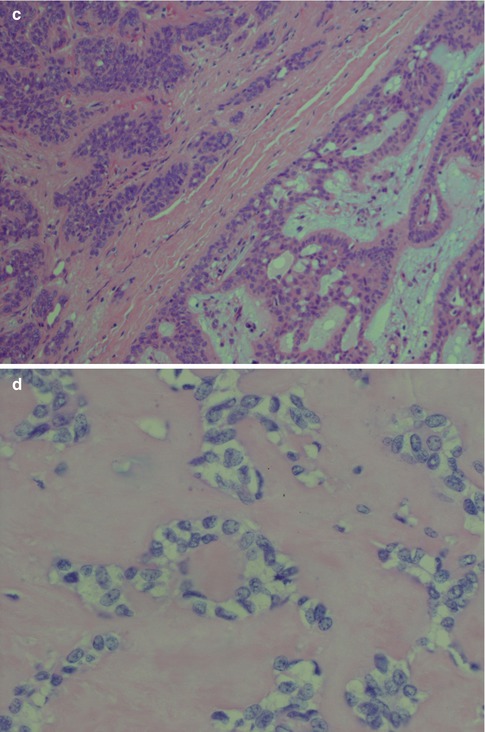

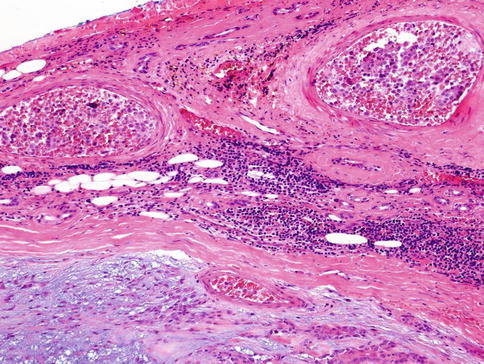

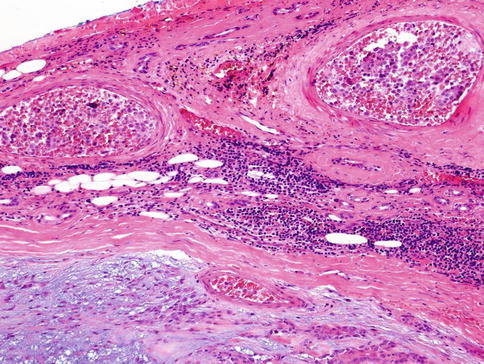

Fig. 3.9

(a) Interlacing fascicles of myoepithelial and ductal cells in a hypocellular and richly vascularised stroma. (b) Strands of myoepithelial and ductal cells with ‘punched out’ cysts or holes similar to those seen in adenoid cystic carcinoma. (c) Higher magnification showing several ‘punched out’ cysts (left) but also ductal columnar cells forming tubules (centre/right). (d) Typical strong positivity for GFAP

Pleomorphic adenoma may show areas of hyalinisation (please see below, PA with atypical histological features) and may be cystic. PA rarely presents with large cysts that can be seen in myoepithelioma. Vascular tumour invasion is another rare but well-known and much debated feature of PA (Fig. 3.10). The biological significance is not known, but the general concept is that this does not indicate malignancy. It may of course be related to the enigma of metastasising pleomorphic adenoma (see below). In a study by Skalova and associates, 22 cases of PA were demonstrated to have intravascular tumour deposits. In seven of these patients, a FNA had previously been performed which possibly could be related to the intravascular tumour deposits. Tumour cells were found in both thin-walled and muscular thick-walled vessels [106].

Fig. 3.10

PA with intravascular tumour invasion

Squamous metaplasia is not an uncommon feature in a number of salivary gland lesions and most commonly seen in necrotising sialadenitis and pleomorphic adenomas. It is usually seen in larger ducts but also as free-lying sheets of epidermoid tissue, sometimes with keratin pearls. Foreign body reaction may be present, possibly reaction to keratin or previous fine-needle aspiration. Occasionally there may in addition also be mucous metaplasia or clear cell change. Cyst formation is not unusual. The squamous metaplasia can be extensive, and cases of pleomorphic adenoma with as much as 95 % of the epithelial component composed of sheets of squamous metaplasia have been reported. Pleomorphic adenoma with these types of metaplastic changes can rather easily be confused with mucoepidermoid carcinoma [22, 43, 47, 64]. A low KI-67 labelling index but particularly a positive myoepithelial profile (S-100, vimentin and SMA) will support a diagnosis of pleomorphic adenoma rather than mucoepidermoid carcinoma (Fig. 3.11). It has previously been estimated that squamous metaplasia occurs in as much as approximately 25 % of pleomorphic adenoma [98], but the incidence is likely higher today due to the much more widespread use of FNA. Squamous metaplasia is one of the most common histological alterations following fine-needle aspiration. Only haemorrhage with inflammatory changes including giant cells, and granulation tissue with subsequent fibrosis, are more common [69]. Squamous metaplasia may be a finding in almost any salivary gland tumour that has been exposed to preoperative fine-needle aspiration.

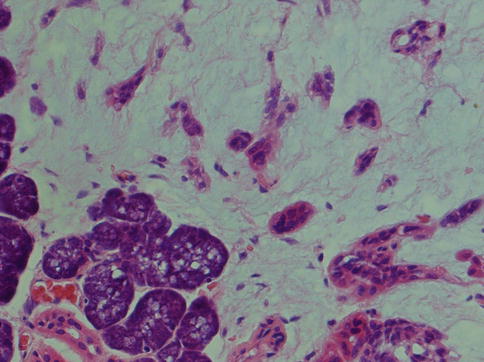

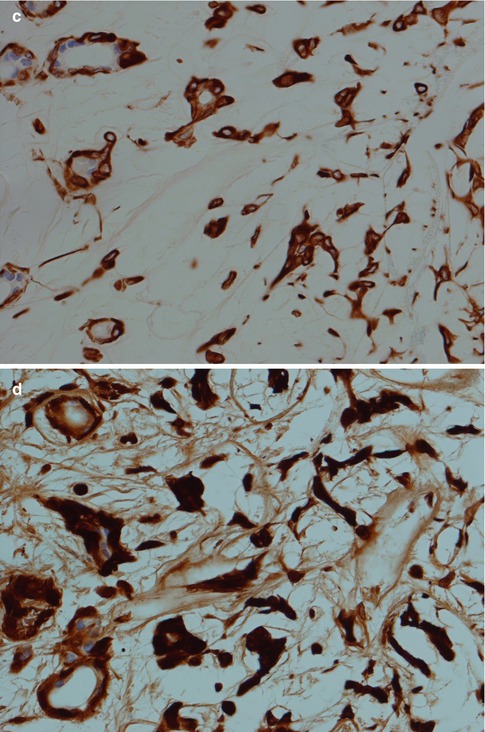

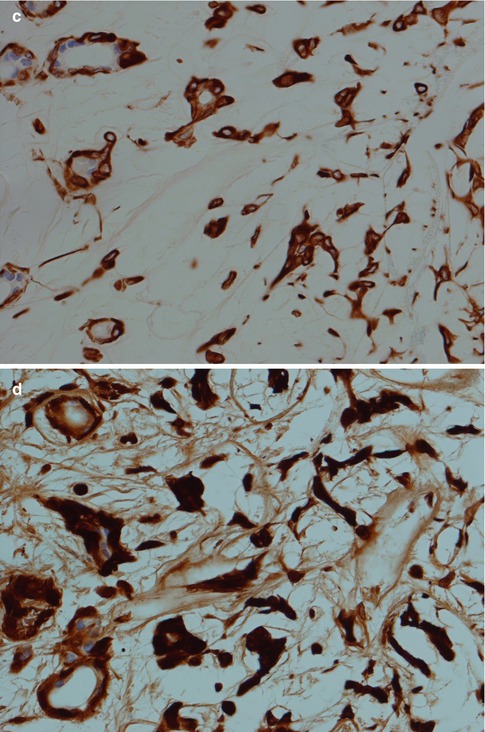

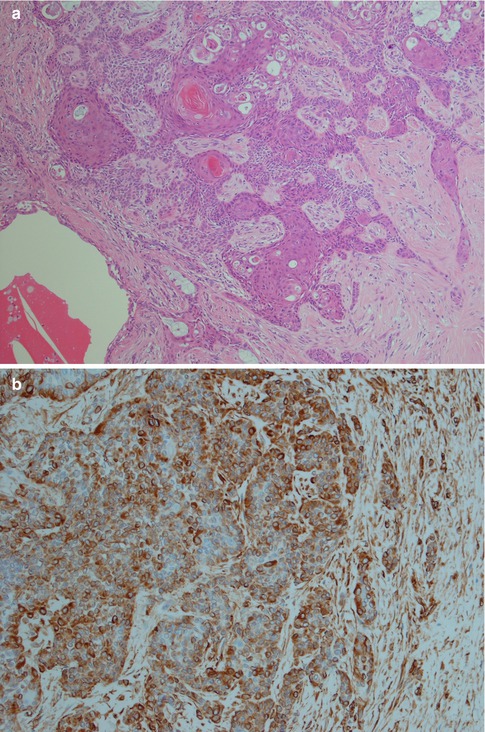

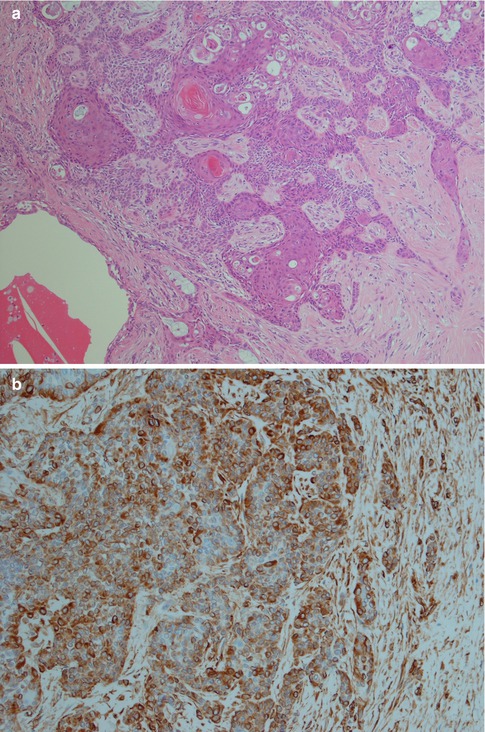

Fig. 3.11

PA with extensive squamous metaplasia. (a) Keratin pearls as well mucous metaplasia and cyst formation. (b) The epidermoid sheets are positive for vimentin. (c) The cells are also positive for S-100. (d) Strong staining CK8/18 in the ductal cyst lining but weak or no staining in epidermoid areas. (e) PA with foreign body reaction (centre)

Oncocytic metaplasia is not as common as squamous metaplasia and is usually present as focal changes. On rare occasions almost the entire adenoma can be affected, and the lesion can then be misdiagnosed as oncocytoma [86]. An oncocytoma consists by definition exclusively by oncocytic cells. The transformation of epithelial cells into oncocytes was formerly regarded as a degenerative process but is more likely to be a re-differentiation. The oncocytic cell is definitively not degenerative in the sense that it is not capable of proliferating and they show luminal rather than myoepithelial immunophenotype. In spite of its luminal immunophenotype, recent studies on gene amplification indicate that at least some of the oncocytic cells may originate from neoplastic pleomorphic adenoma cells, some of which being myoepithelial cells [25]. In tumours with extensive oncocytic metaplasia and clear cell change, such a pleomorphic adenoma may be confused with acinic cell carcinoma. The cytoplasmic granules in an oncocytic acinic cell carcinoma stain with PAS and are resistant to diastase digestion, whilst oncocytic cells in non-acinic tumours are not resistant to diastase (Fig. 3.12). Further, the acinic carcinoma cells are usually PTAH negative and amylase positive, whilst the reverse is applicable for oncocytic cells (see also Chaps. 6 and 9). In cases of oncocytic metaplasia with prominent clear cell changes, metastatic renal carcinoma can have overlapping histology. CD10 and CK20 are the most useful markers in these instances as most metastatic renal cell carcinomas are positive for CD10, variable positive for RCC (renal cell carcinoma marker) and negative for CK20, whilst oncocytic salivary cells can be positive for CK20 but are negative for CD10. EMA, CK7, vimentin and renal cell carcinoma marker are not as useful [84].