Chapter 8 Traditional plant medicines as a source of new drugs

HISTORICAL DIMENSION

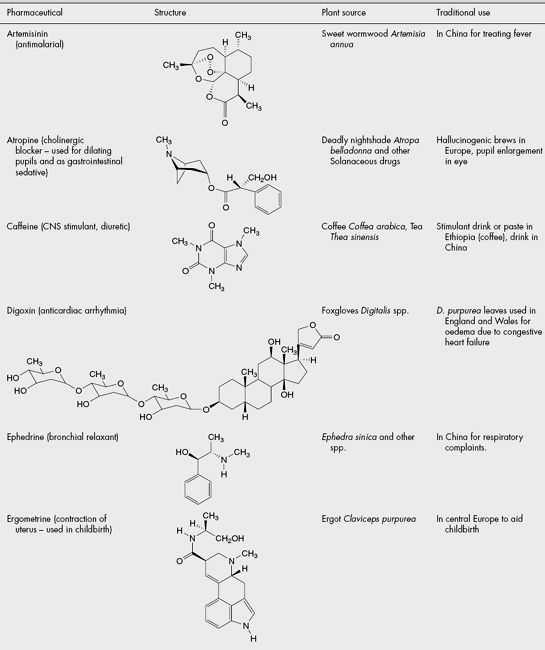

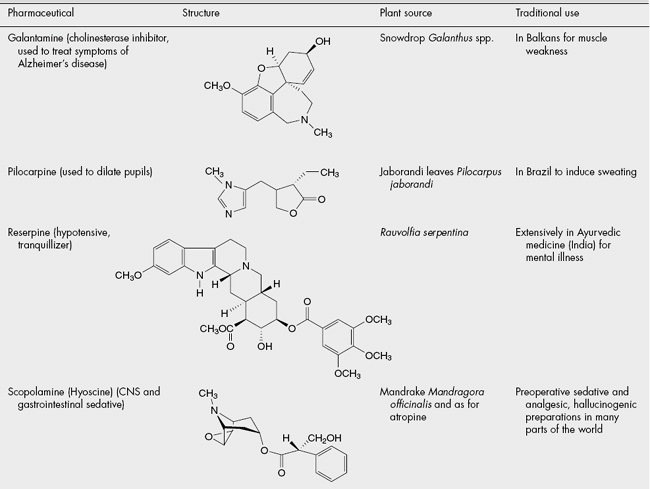

The isolation of some of the opium alkaloids in the early nineteenth century was a key event in the development of modern pharmacy. It showed that isolated compounds had much the same activity as the existing ethnopharmacological material and so paved the way for current orthodox Western medicine, which uses pure compounds for treatment. Since then, a vast amount of money has been spent on the synthesis of novel compounds but also on the isolation of molecules from natural sources and their development into medicines. The contribution of traditional plant medicines to this process has been significant and some notable examples are shown in Table 8.1.

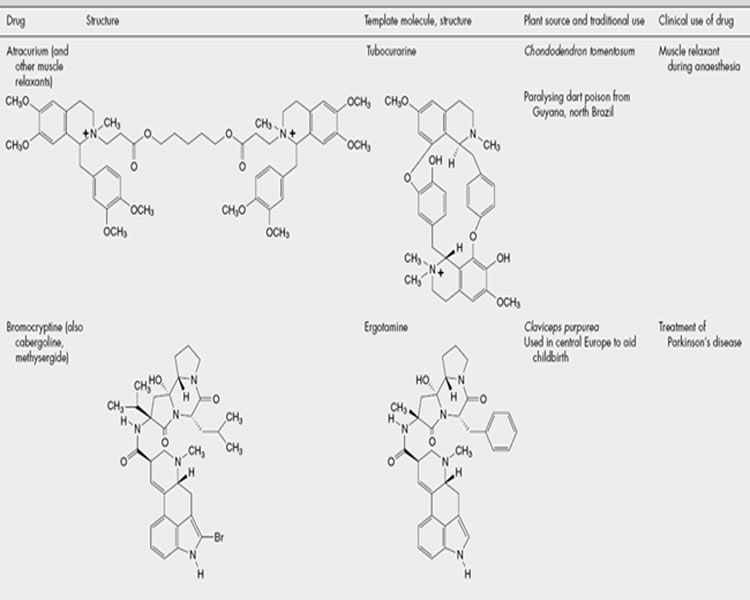

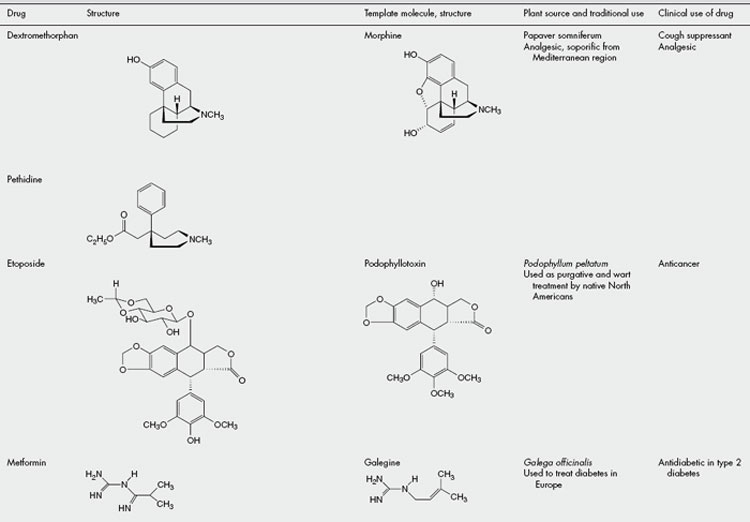

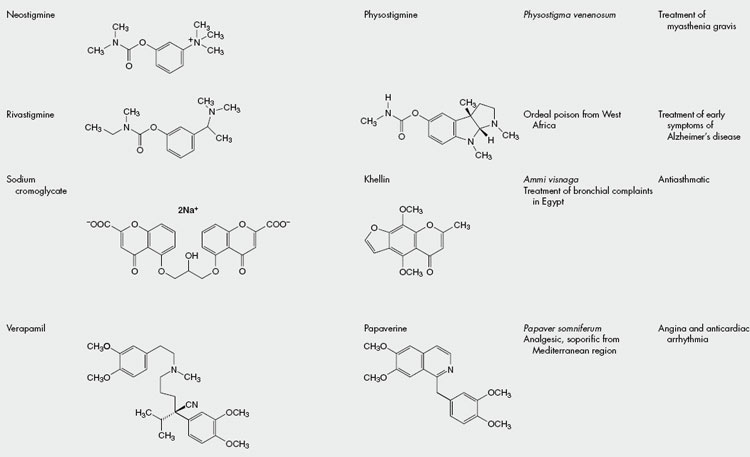

It should also be remembered that the active molecules isolated from traditional medicinal plants might not only provide valuable drugs butare also valuable as ‘lead molecules’, which might be modified chemically or serve as a template for the design of synthetic molecules incorporating the pharmacophore responsible for the activity. Examples of drugs having this origin are shown in Table 8.2.

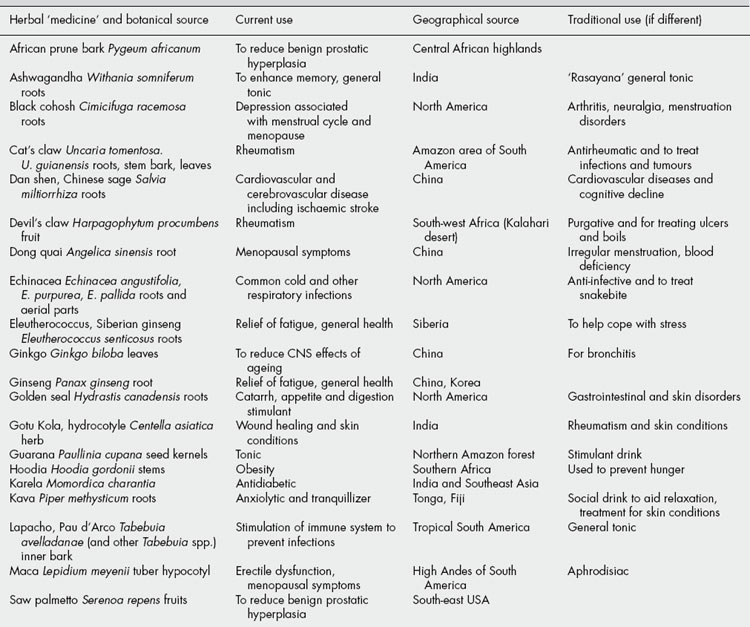

Although the term ‘drug discovery’ is generally used to refer to the isolation of molecules with activity, it should also be remembered that there is increasing interest and recognition that a ‘drug treatment’ might consist of a mixture of compounds. This has always been the case for plant extracts (and most other natural substances), which contain several ‘active ingredients’. It should be noted that such extracts, usually based on a reputed traditional use somewhere in the world, are being introduced and increasingly used as a complementary therapeutic approach in the West. A selection of common ones, together with their ethnopharmacological roots, is shown in Table 8.3.

Although primarily concerned with human aspects, there has been a recent upsurge of interest in veterinary ethnopharmacology, i.e. methods and materials used to treat animals, particularly those important to the local economy as providers of food, transport and fibres. Other expansions from a strict definition of ethnopharmacology as being the study of medical practices include aspects of plants and other materials used in the diet, those used for ritualistic purposes, for poisons of various types, as cosmetics and as adjuncts to social gatherings. The increasingly blurred distinction between food and medicine, which has become a notable feature in ‘Western’ society, is a situation that has always been the case in other medical systems, such as Ayurveda and TCM, and it is now widely recognized that particular plants comprise part of the regular diet as much as for health maintenance as fortheir macronutritional properties. Attention has also been focused on the ways in which the role of a substance can change through time or as it is transferred from one culture to another. Thus, coffee was thought of as primarily medicinal when it was first introduced into northwest Europe in the seventeenth century, but quite rapidly became a beverage. It is also of interest that cultural restraints might minimize abuse of a substance in its indigenous context but that, when these restraints are removed as the plant begins to be used in another part of the world or society, it becomes a problem to that society. An example of this situation is seen with the abuse of kava-kava in Australia by aboriginal peoples, who do not have the framework of ritualistic use of these roots in the Pacific islands of Fiji and Tonga, where it originates.

Several recent surveys have shown that using ethnopharmacology as a basis of selecting species for screening results in a significant increase in the ‘hit rate’ for the discovery of novel active compounds compared with random collection of samples. It should be noted that several ‘classical’ drugs stated to have derived from ethnopharmacological investigations, e.g. several shown in Table 8.1, arise from plants known as poisons rather than those with a more ‘gentle’ action, which comprise the bulk of many herbal medicine species. The latter group often relies on a mixture of compounds with a mixture of activities, where synergism and polyvalence might be occurring, and where the isolation of one ‘active constituent’ is much less likely.

THE PROCESS OF MODERN DRUG DISCOVERY USING ETHNOPHARMACOLOGY

The discovery process is composed of several stages. The first stage must be the reported use of a naturally occurring material for some purpose that can be related to a medical use. Consideration of the cultural practices associated with the material is important in deciding possible bases of the reputed activity. If there is an indication of a genuine effect, then the material needs to be identified and characterized according to scientific nomenclature. It can then be collected for experimental studies, usually comprising tests for relevant biological activity linked with isolation and determination of the structure of any chemicals present that might be responsible. The ‘active’ compounds are usually discovered by several cycles of fractionation of the extract linked with testing for the activity of each fraction, until pure compounds are isolated from the active fractions, a process known as bioassay-guided fractionation. These compounds, once their activity is proven and their molecular structure ascertained, serve as the leads for the development of clinically useful products. These various stages are discussed in detail below.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree