• Answer the same key question(s) of interest

• Provide appropriate and timely information

• Offer feasible and reasonable approaches to answering the key question(s), solving a similar problem, or meeting specific needs

• Represent findings from similar situations or settings or among similar populations

• Use best practices to conduct the review and report its findings

• Engage relevant stakeholders in the design, conduct, and interpretation of the review findings

If the search identifies a review that meets most of these criteria, its findings may be adequate to answer the question at hand, prompt the implementation of findings in a specific setting, “tee up” research based on research gaps identified in the review, or inform program or policy design.

If the identified reviews do not include recent literature on the key question(s), the review developer may choose to update the existing review. In this case, the review developer may have a significantly shortened planning process because it should be possible (and preferable) to replicate the prior review’s SR protocol as closely as possible with at least one notable exception—the inclusion dates for the review. The new review should start where the prior review ended and continue to the most recent, reasonable date. After searches for the new review are complete, the analysis can be replicated by either combining all the data, as would be necessary for a meta-analysis, or by examining the new findings and then doing a cross-walk with the findings of the existing review, an approach more suited to a qualitative synthesis strategy of determining review findings.

If the search for reviews is unsuccessful, the review developer may elect to complete a planning process for a new SR, taking into account the resources necessary to conduct the review and the research developer’s capacity to undertake the review. Reviews of complex questions can be quite expensive and time consuming, so a consideration of the costs and time constraints is very important in deciding to conduct a review. In the context of the Health Scenario, for example, the nurse researcher would likely need to engage the services of a reference librarian to identify the most efficient search strategy for the literature; find a colleague to be a second reviewer of abstracts and articles; and develop a process to involve community members in planning, conducting, and interpreting the SR findings. Each of these steps requires a consideration of how financial support will be obtained to cover the time individuals spend on the SR and other expenses associated with the review such as article retrieval.

Plan Development Steps

Methods and processes to create an SR plan are recommended by primary developers of SRs. We present our adaptation of the IOM Standards for Systematic Reviews published in 2011 as an orientation to the essential components of an SR plan. It is vitally important to document decisions made for each step so that the chosen approaches can be described in the presentation of SR findings. More details on how to approach each step can be found at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Finding-What-Works-in-Health-Care-Standards-for-Systematic-Reviews/Standards.aspx (IOM, 2011).

We offer approaches to each of seven steps necessary to plan a “new” review such as the one needed by the church leader and the nurse researcher to answer the following question: Is community-based screening for previously undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus among African Americans as effective in identifying affected individuals as is clinic-based screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus?

Step 1

Establish a team with appropriate expertise and experience to conduct the SR. The team should include individuals with expertise in the pertinent content areas, SR methods, searching for relevant evidence, quantitative and qualitative methods, and other expertise as appropriate.

Approach: The nurse researcher will confer with academic colleagues to identify members of an SR team with experience in designing and conducting SR and in methods necessary to conduct the SR. Individuals may be invited to join the team based on their experience in relevant content areas such as diabetes screening and treatment; primary care, especially as delivered in rural areas; and ways to reach underserved individuals in rural areas. A research librarian with experience in conducting searches for SR or for complex topics would be recruited along with a researcher well versed in the use of qualitative methods. This SR is not likely to need an expert in quantitative methods such as meta-analysis given the type of literature on this topic.

Step 2

Manage bias and conflict of interest (COI) of the SR team conducting the SR. A process should be established to require each team member to disclose potential COI and professional or intellectual bias, exclude individuals with a clear financial conflict, and exclude individuals whose professional or intellectual bias would diminish the credibility of the review in the eyes of the intended users.

Approach: Most academic institutions have COI processes in place, and if all team members are part of that process, the team leader may proceed to document any reported COI or inquire about any further COI that may be present given the location, content area, or scope of the SR. For any members of the team whose organizations may not require a COI, the team leader should establish a process for identifying and documenting COI. In some cases, it may be necessary to reconsider membership by a specific team member based on his or her declared COI.

Step 3

Ensure user and stakeholder input as the review is designed and conducted. Although user and stakeholder input is vital to planning the review, a process should be in place to protect the independence of the review team to make the final decisions about the design, analysis, and reporting of the review.

Recent efforts by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and others seek to assure greater transparency of the SR processes and to engage patients and other stakeholders in the review process. Stakeholder groups are identified variously by SR developers but are generally assumed in the areas of health and health care to include patients and their caregivers; clinicians, including physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals; payers; and policymakers, including guideline developers and other SR sponsors.

Patient and stakeholder involvement in each step of the SR process is critical. Their perspectives inform the development of key questions, primary and secondary outcomes, analytic frameworks, strength of evidence, and interpretation of findings. Including these perspectives help to ensure that reviews address outcomes meaningful to patients and other stakeholders and provides actionable recommendations for all stakeholder groups and their members.

Stakeholder participation may be hampered by their awareness and understanding of methods used to conduct an SR; their bias for or against SR processes, findings, and applications; their interpretation of the implications of review findings for themselves and their organizations; and their understanding of their role in the SR process.

Principles of community engagement can be applied to increase the quality of stakeholder involvement in SR processes. Stakeholders can be offered orientation sessions describing their roles and responsibilities as stakeholder advisory panel members. They can also be offered training to increase their knowledge of the SR process and appreciate the strengths and limitations of an SR. Materials associated with planning the SR can be presented in “plain language,” and ample time can be given for discussion or clarification.

Just as stakeholders may need to gain familiarity with the SR process, some review team members may need to learn more about the contextual and other factors affecting the topic of the review from the stakeholder perspective. This bidirectional learning is likely to enhance the relevance, credibility, and acceptance of review findings.

Approach: The church leader and nurse researcher spent time together to develop a list of potential stakeholders to advise their review team. Because individuals and groups in Bamberg County are the most likely short-term users of the SR findings, they decided to form a stakeholder advisory panel composed of county and state residents representing adults with and without diabetes (three members), clinicians and other health care professionals who regularly participate in screening events in the community and within the health care system (two members), a representative from the primary insurers of individuals in the county (Medicaid and Medicare program representatives) (one member), community leaders from the faith-based community (two members), a member of a local advocacy group for patients with diabetes (one member), and a policymaker such as a local member of the legislature (on member). They think that this group of 10 individuals represents most of the major stakeholder groups and that the number will be manageable from a logistical perspective. One of the review team members will be identified as the primary point of contact for the stakeholder advisory panel.

Step 4

Manage bias and COI for individuals providing input into the SR. Similar to the process for COI for review team members, individuals providing input to the review should be required, through a transparent, consistently used and applied process, to disclose potential COI and professional or intellectual bias. A process should include an approach to identifying and excluding from individuals whose COI or bias would diminish the credibility of the SR in the eyes of the intended users.

Approach: The review team’s point of contact will develop, with stakeholder input, a process for assuring identification and disclosure of COI for members of the stakeholder advisory panel.

Step 5

Formulate the topic for the SR. In this step, the review team should confirm the need for a new review and develop an analytic framework that clearly lays out the chain of logic linking the health intervention to the outcomes of interest and defining the key questions to be addressed by the SR. A standard format to articulate each question of interest should be developed that states the rationale for each question. Key questions should be shared with intended users and stakeholders and refined, if necessary, based on their input. Types of questions may encompass clinical, behavioral, systems, or policy concerns in a particular field (IOM, 2011).

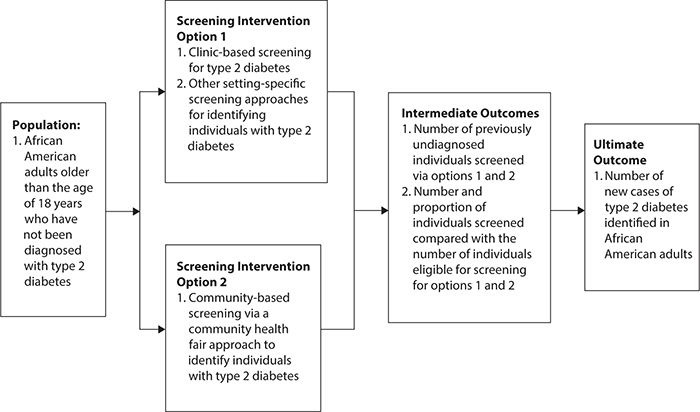

Approach: During the first combined meeting of the review team and the stakeholder advisory panel, a new key question is developed from the original PICO statement: for the population of African American adults older than age 18 years, is the proposed intervention of a community health fair more or less effective compared with other diabetes screening options such as clinic-based or other interventions to affect the outcome of increasing the percentage of adults screened for diabetes in a specific geographic area? During this meeting, the review team presents a preliminary analytic framework developed to link the PICO elements together and frame the review (Figure 12-1). The combined group agrees that this analytic framework is appropriate for taking the next two steps in the planning process.

Figure 12-1. Analytic framework for a systematic review to compare community versus clinic-based screening options to increase the number of individuals screened for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Step 6

Develop an SR protocol describing the following elements of the SR process:

1. The context and rationale for the SR from both a decision-making and research perspective

2. The study screening and selection criteria (inclusion and exclusion criteria)

3. The precise outcome measures, time points, interventions, and comparison groups to be addressed

4. The search strategy for identifying relevant evidence

5. The procedures for study selection

6. The data extraction strategy

7. The process for identifying and resolving disagreement between researchers in study selection and data extraction decisions

8. The approach to critically appraising individual studies

9. The method for evaluating the body of evidence, including the quantitative and qualitative synthesis strategies

10. Any planned analyses of differential treatment effects according to patient subgroups, how an intervention is delivered, or how an outcome is measured

11. The proposed timetable for conducting the review

12. The conduct and timing of a public comment period for the protocol and publicly report on disposition of comments (IOM, 2011)

Approach: The review team develops a draft of the protocol in consultation with its expert members and with input from the stakeholder advisory panel as necessary. The iterative process is completed in about 6 months and defines the scope and conduct of the review to answer the key question.

Step 7

Submit the protocol for peer review.

Approach: The final protocol is made publicly available via email and an online posting to all members of the review team and the stakeholder advisory panel. Members share the protocol with their constituents along with a timeline for submitting comments on the protocol. Comments received during this time frame are compiled, and preliminary answers are prepared by the review team for joint discussion and consideration with the stakeholder advisory panel. Any necessary adjustments are made as amendments to the protocol and communicated to all relevant stakeholders.

SUMMARY

An SR is a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular issue. Typically, an SR relies principally on the results of investigations that are published in the peer-reviewed literature but may also include “grey” literature (e.g., unpublished manuscripts, conference papers and posters, grant close-out reports) The findings of an SR may be summarized in a variety of ways, ranging from a qualitative assessment to a formal statistical summary referred to as a meta-analysis.

Systematic reviews are useful to a range of stakeholders, from patients and patient advocates, to care providers, professional societies, payers for health care services, researchers, and policymakers. The conduct of an SR typically follows a standardized process. First, a question of primary interest is formulated around considerations of populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes (PICO). An SR also must specify the types of studies to be included, a time period for the literature to be reviewed, and any underlying assumptions about the relationships of the parameters that serve as a basis for the key elements of the PICO.

Systematic reviews are most useful if they are relevant to the population of interest, are timely, address the critical PICO elements, engage stakeholders in their design and conduct, and use best practices from initial development through final interpretation. If an SR has been conducted and published already, the need for a new review may be obviated. Often, however, there is no existing SR on the topic of interest, it may not apply to the population of interest, or it is out of date. Under these circumstances, one might entertain conducting a new SR.

Planning and conducting a formal SR should follow well-established guidelines, focusing on the topic of interest, assembling an interprofessional team to work together, identifying potential stakeholders from various interested parties and soliciting their input, identifying and managing any conflicts of interest, developing a protocol, and submitting the protocol for peer review. In the following chapters, the elements of performing an SR are presented in detail.

1. A systematic review is

A. a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular issue.

B. a review of the literature for a topic relevant to health and health care.

C. always a meta-analysis.

D. a fair and balanced way to review available evidence.

2. PICO stands for

A. patients, interventions, consultations, and outcomes.

B. populations, inventions, comparisons, and observation.

C. populations, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes.

D. patients, inventions, comorbidities, and outcomes.

3. Which of the following is not true about systematic reviews?

A. Researchers and other persons developing systematic reviews use an organized method of locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature on a particular topic using a set of specific criteria

B. A systematic review typically includes a description of the findings of a collection of research studies

C. A systematic review may tailor presentation of findings for specific target audiences, including the general public

D. Systematic reviews present findings using only quantitative methods

4. Which item is not an expected outcome for a systematic review plan?

A. A well-framed question or set of questions specifying the PICO

B. A statement of what types of studies are to be included in the review (e.g., clinical trials, observational studies)

C. A description of how stakeholders are to be involved in the review

D. A description (often a logic model or analytic framework) that describes the relationship of PICO elements to one another

5. An existing review would be most helpful if it addressed all but one of the following items:

A. provided appropriate and timely information.

B. offered feasible and reasonable approaches to answering the key question(s), solving a similar problem, or meeting specific needs.

C. used best practices to conduct the review and report its findings.

D. answered a slightly different but very similar key question.

6. Which of the following is not a type of grey literature?

A. Unpublished manuscripts

B. Conference papers and posters

C. Newspaper articles

D. Grant close-out reports

7. Which of the following groups would be likely stakeholders in a systematic review of community-based screening for diabetes?

A. Insurance payers

B. Health care providers

C. Community leaders

D. All of the above

8. A prior published systematic review may be deemed not useful for addressing a subsequent issue because of

A. the study populations included.

B. all relevant literature was not included.

C. the review and its source studies are not current.

D. all of the above.

9. Which of the following stakeholders has a potential conflict-of-interest in advising a systematic review on the topic of community-based screening for diabetes mellitus?

A. A diabetes expert who also serves as a paid consultant to a pharmaceutical company

B. A physician in a clinic that serves the community and moonlights in emergency departments

C. An administrator with the state Medicaid agency

D. A retired school teacher who lives in the community and volunteers with various not-for-profit organizations

10. Which of the following is NOT an essential of the protocol for developing a systematic review of the comparative effectiveness of community-based versus routine clinical screening for diabetes in an African American community?

A. Define the criteria for selecting individual studies for inclusion.

B. Identify the outcome measures, interventions, and comparison groups of interest.

C. Exclude all studies that have not been published in the peer-reviewed literature.

D. Extract the key data elements from the selected studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree