6 Physical examination and clinical investigation

Other ways of knowing

The Nature of Physical Examination

• Hearing: hoarseness in the patient’s voice; a cough; laboured or altered breath sounds; or sniffing. All these phenomena could be detected in a preliminary telephone consultation before seeing the patient for the first time

• Seeing: the patient’s difficulty in rising from a chair; observing their posture and gait; tremor; skin tone and colouration. Such significant areas of examination can be noted from the time of first greeting a patient in the waiting room, to the moment they sit down in the consulting room

• Touching: the patient’s hand when shaking it for the first time provides information regarding temperature and moisture or dryness; as well as strength or frailness; hesitancy or confidence

• Smelling: tobacco, alcohol, urine, etc., odour around patient; this can be one of the earliest and strongest sensory impressions.

• The practitioner’s approach to handling bodies – in general and in particular. There is a difference for example, between sensory and sensual engagement; and between an appropriately ‘clinical’ manner and objectification of the patient’s body

• Whether the practitioner demonstrates positive regard or disregard for the patient

• Whether the patient is processed mechanically or tended organically

• Whether the reasons triggering formal examination have been clearly explained and justified

• The practitioner’s skill and fluency

• The degree to which the patient’s comfort is catered for and their modesty respected.

The classical interpretation of the role of the physical examination is dual:

• To provide a means of testing hypotheses regarding differential diagnoses that have been generated during the case history (directed examination)

• To scrutinize the patient for additional new information regarding their condition (general examination, or routine screening, such as taking the pulse and blood pressure).

These represent entirely diagnostic goals, which do not fully account for the urge to examine. The predicaments and conditions of many patients (such as those classed as mood disorders) are not readily suggestive of the need for formal physical examination of any particular type, while many of the presentations that do indicate the involvement of a body system that is susceptible to examination fail to yield classical findings. In the latter case, either nothing of obvious consequence is found or the significance of the findings are unclear or deemed of poor legitimacy, e.g. generalized mild abdominal tenderness in the absence of other signs is conventionally read as indicating that, whatever the problem is, it probably isn’t serious. While classical findings may be encountered relatively frequently in acute or severe pathology, they are rather rare in day-to-day practice outside of hospitals. Routine physical examination is typically similarly unproductive in generating clear evidence of pathology. The value of physical examination is brought into further question by the superior ability of many laboratory and technological techniques to see into the body and by the rise of evidence-based physical examination, which has highlighted the deficiencies of many examination techniques, as we will see shortly. Despite all this, however, physical examination continues to be taught as an essential facet of the consultation. In my view, Greaves (1996) critique of, and rationale for, the use of physical examination in conventional medicine could apply equally to herbal practitioners:

Examination Versus Investigation

‘Physical examination’ is also known as ‘physical diagnosis’ and ‘clinical examination’. It can be contrasted with ‘clinical investigation’, which refers to laboratory and other types of testing such as blood studies and imaging techniques. A group of differences between ‘examination’ and ‘investigation’ are implied here and are summarized in Table 6.1. The two key distinguishing features between these two notions have to do with the proximity of the practitioner to the patient, and with the means applied to make the assessment.

Table 6.1 Summary of differences between physical examination and clinical investigation

| Examination | Investigation |

|---|---|

| Performed by the practitioner | Performed by another |

| Embedded in the consultation | Occurring outside of the consultation |

| Human | Mechanical |

| Sensory | Technological |

| Personal | Abstract |

| ‘Soft’ evidence | ‘Hard’ evidence |

| Considered subjective | Considered objective |

| Immediate results | Mostly delayed results |

| Generally non-invasive | More likely to be invasive |

| Very low to no risk of adverse effects | Adverse effects more likely |

Physical examination is an attempt to conjecture from manifestations appearing on the surface of the body about what may be taking place inside of it. Ancient systems of medicine developed sophisticated schemas of interpretation around key examination areas such as those of the pulse and tongue to the extent that these were relied upon to provide definitive accounts of the patient’s condition. (Previously, we quoted Kuriyama 1999: ‘In the second century B.C.E., in the earliest case histories of China, the sick summon Chunyu Yi not with vague pleas for succor, but with the specific wish that he come and feel their pulse’.) The pulse remains a ‘vital sign’ in biomedicine but it is not felt anymore – rather it is counted or transmogrified into a line on an ECG trace, the varied and multiplied forms of which suggest the outlines of mountains in early Chinese landscape art.

In Chinese medicine, the pulse is categorized with words such as: floating, deep, empty, slippery, choppy, soggy, hollow, scattered, wiry, overflowing, knotted, hasty; words which relate to natural phenomena and qualities drawing on such reference points as the properties and activities of water. Pulses are further described and taught in terms that relate to the natural world, for example, regarding the ‘slippery’ pulse: ‘In ancient times, it was described as feeling like ‘pearls rolling in a basin’ or ‘raindrops rolling on a lotus leaf’’ (Maciocia 2004). In contemporary biomedicine the lexicon relating to the pulse retains some connection with the natural world (fast, slow, full, empty, bounding, collapsing) but is primarily concerned with the number of beats and their rhythm. The music of beats and rhythms is considered to be ‘heard’ better by machines so that heart monitoring, such as by the ECG, is taken as the ultimate authority on the patient’s situation. The technical language associated with this type of investigative scrutiny is accorded greater credibility than the nature-terms used in examination – the precision of identifying a ‘variable PR interval’ is preferred to physical detection of an ‘irregularly irregular’ pulse.

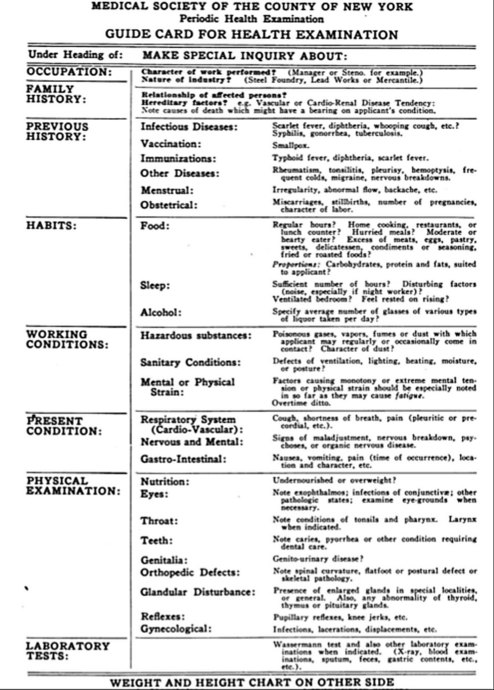

The idea of providing periodic health examinations to ‘apparently healthy persons’ (Dodson 1925) crystallized in the 1920s and began to be variably implemented from that time. The format of the examination differed across America at the outset and has never been universally standardized. An early example of a ‘Guide Card’ for the examination is shown in Figure 6.1. This shows that the ‘examination’ combined history-taking (including focus on diet and work-related issues) with a mix of physical examinations and minimal reference to ‘laboratory tests’ ‘when indicated’ (Thomson 1925).

Prochazka et al. (2005) showed that the annual physical examination is today based largely on a range of blood tests (such as lipid panel, liver function tests, thyroid and complete blood count) and urinalysis as well as height, weight and blood pressure measurements and cervical smears and mammograms in women, with these ingredients being variously combined. Investigation has moved from an optional extra in the 1920s to occupy centre stage in the early twenty-first century. The authors questioned public and practitioner attitudes towards the examination and contrasted their background understanding that: ‘Current evidence does not support an annual screening physical examination’, with their study findings that ‘a relatively high percentage of the general public desired an annual physical examination’ and that most primary care physicians believe that such an examination ‘detects subclinical illness’. Interestingly, while 63% of physicians believed that the examination was of proven value (contrary to the evidence), ‘94% believed that an annual physical examination improved the physician–patient relationship and provided valuable time for counselling on preventive health behaviours’. This latter belief returns us to Greaves’ insight that, beyond diagnosis, physical examination ‘would seem to have an additional significance’ and adds to our earlier discussion of the extra dimensions of the examination.

Following a personal reflection on the issues surrounding the annual physical examination Laine (2002) concludes that:

In an accusation that could be levelled more generally at the change in emphasis of conventional medicine as a whole over the course of the twentieth century, Han (1997) contends that the American annual physical examination has changed:

Evidence-Based Physical Examination

Perhaps surprisingly, Reilly (2003) was able to observe that:

In response to research suggesting that there are ‘widespread deficits in the physical examination skills of practising physicians’, Ortiz-Neu et al. (2001) investigated the competency of 3rd-year medical students in conducting cardiovascular examination in eight medical schools, concluding that their results suggested: ‘fundamental inadequacies in the current paradigm for teaching physical examination skills’. Other authors (such as Bordage 1995) have expressed concern regarding the decline of the emphasis on, and competence in, physical examination skills on the part of medical students and physicians. My experience, as a teacher and examiner working with herbal medicine students and practitioners suggests that physical examination skills are often inadequately taught (teaching is frequently partial, rushed, with insufficient time allowed for practise); that a desirable level of examination-related knowledge and fluency is rarely achieved by the time of the final clinical examination; and that herbal practitioners soon reduce their use of physical examination techniques to a narrow base when in practice.

Physical examination is a largely subjective art and a number of papers have found poor interexaminer (or ‘interrater’) reliability in conducting particular examination techniques (such as Yen et al. 2005, looking at abdominal examination of children), while others have found a good degree of reliability (such as Weiner et al. 2006, studying examination of chronic lower back pain). One issue here has to do with the degree of expertise possessed by the examiner. For example, a skilled examiner who is able to help patients relax and who uses ‘reinforcement’ (a technique that causes momentary relaxation of the body part being examined) in testing reflexes is more likely to be able to elicit them.

A further concern regarding the value of physical examination is raised by studies that have shown certain investigative techniques to be superior to examination techniques in particular cases. For example: Kolb et al. (2002) found that combined mammography and ultrasound was superior to palpation in detecting small breast cancers; Spencer et al. (2001) showed that the use of a portable echocardiography device was more effective than physical examination in assessing the heart in cardiovascular patients; Wipf et al. (1999) showed that chest examination was unable to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pneumonia and that X-rays provided the best diagnostic test. None of these studies called for the abandonment of physical examination however, some (e.g. Spencer et al. 2001) have drawn attention to the areas of strength as well as weakness for examination techniques, but all have suggested the need to become more aware of the accuracy and reliability of physical examination. Other studies have clarified the value of examination. For example, in a small study, Nardone et al. (1990) explored the value of physical examination in suggesting whether patients had anaemia. They looked at pallor in the conjunctivae, face, nails, palms and palmar creases and concluded that ‘the absence of pallor does not rule out anaemia’; that examination of nailbeds and palmar creases was of no value in assessing anaemia; and that if combined pallor of the conjunctivae, face and palms was found this did indicate the presence of anaemia.

In the foregoing discussion, we have drawn on the developing evidence base for physical examination, which has both raised and addressed concerns regarding the credibility of this part of the consultation. An influential paper in developing the notion of evidence-based physical examination was that of Sackett and Rennie (1992), which justified and introduced a series of articles in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) that scrutinized examination methods. The authors first noted the value of physical examination in:

• Frequently providing ‘everything we need to clinch a diagnosis’ (ruling in)

• Permitting ‘us to rule out diagnostic hypotheses’ (ruling out)

• ‘Developing rapport with, and understanding of, our patients’

Subsequent JAMA articles appeared under the banner of ‘rational clinical examination’, eventually leading to the publication of a book with that title (Simel & Rennie 2009). An earlier attempt at providing a manual of Evidence-based physical diagnosis was made by McGee (2001). The work done by these authors in increasing the scrutiny applied to physical examination amounts to an effort to save it, as if it were an endangered species, in the face of a movement that considers, as McGee put it: ‘that physical diagnosis has little to offer the modern clinician and that traditional signs, although interesting, cannot compete with the accuracy of our more technologic diagnostic tools’.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree