Pharmacy information systems are, simply put, the computer systems that the pharmacy uses to manage all the information required to care for patients.1 Although such systems may appear straightforward at first glance (see Figure 7-1), they accommodate some of the most important clinical, documentation, and communication functions in the pharmacy, such as

- Clinical screening for drug interactions

- Prescription order entry

- Prescription and inventory management

- Patient profiles

- Reports of medication use

- Interactions with other systems related to payment, regulatory compliance, and so on

These systems have led to many improvements in data management and patient safety, including faster processing of orders and prescriptions, reduced medication errors, and improved adherence to medication-use policies or drug formularies (see Chapter 13) within an institution.2,3 Table 7-1 includes some terminology related to pharmacy information systems and their most common functions, as described below.

Clinical Screening

When information is entered into the patient profile, the pharmacy information system stores the records and applies the information to future prescriptions filled in the pharmacy. The pharmacy computer screens a patient’s medication list, drug allergy information, current or former smoking or alcohol history, pregnancy status, age, weight, and much more information every time a new prescription or medication order is entered. Some pharmacy information systems also allow you to document previous medication adverse events or patient risk factors. When entering information into the computer, be complete and accurate to ensure that all data are correct and properly updated.

|

DEFINITION |

|

|

Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) |

Physicians or other providers enter medication orders directly into the computer system on the patient-care unit or floor instead of transmitting a written or verbal order to the pharmacy for order entry. |

|

Electronic medical record (EMR) |

An electronic or digital version of a patient’s chart that allows providers to track patient data, identify ongoing patient needs, monitor specific laboratory or other parameters over time, and handle many other components of a patient’s care within a single pharmacy or institution. |

|

Electronic health record (EHR) |

Similar to an EMR, but often provides additional information about the patient’s history outside of a single institution. In some cases, patients may have access to their EHR information when they see providers in different institutions or practices. |

|

Clinical information system |

A computerized pharmacy information system that also provides information on the clinical care of patients, such as electronic medication administration records, laboratory and other patient data, and diagnoses. |

|

Clinical decision support (CDS) |

Electronic tools to help pharmacists, physicians, and other providers or individuals involved in health care make informed decisions about treatment or other options. CDS systems may include drug-interaction alerts with alternative treatments, predetermined order sets for high-risk medications, links to clinical guidelines, and many other resources. |

|

Electronic prescribing (e-prescribing, e-Rx) |

Computer-based generation and transmission of a prescription directly from the prescriber, usually to an outpatient or mail-order pharmacy. In contrast to CPOE, which generally occurs within a single closed system, e-prescribing transmits a prescription electronically between separate systems (e.g., from the provider’s office to the pharmacy), taking the place of paper, faxes, or telephone orders. E-prescribing can reduce medication errors because it removes subjective factors such as illegible handwriting, but it may also introduce new types of errors, such as a prescriber selecting the wrong medication from a drop-down menu. |

Prescription Records and Management

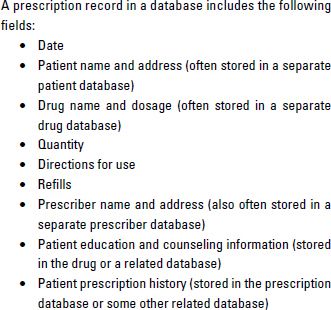

At minimum, a patient’s prescription record will include basic information about their current and past prescriptions (Table 7-2). Although specific details depend on which computer system your pharmacy uses, nearly all pharmacy systems use prescription records in the dispensing process. Many also interface prescription records with inventory to verify if a specific product is in stock or even track which stage of dispensing any given prescription or medication order is currently in. As a technician, understanding the prescription records and management components of your pharmacy’s information system will be a key to your success in the pharmacy.

Inventory Management

With the number of drugs and pharmaceutical products on the market, it would be nearly impossible to keep track of pharmacy inventory (see Chapter 13) without computerized systems. Pharmacy computer systems are often used to maintain accurate counts of current inventory, display an alert when products go below a preset quantity, identify appropriate suppliers for product replacement, or automatically reorder products.

Patient Profiles

Although the patient profile serves as the electronic repository of the patient’s drug and medical history, it has grown to serve many more functions. In a community chain pharmacy, patient profiles are often integrated among different pharmacy locations to facilitate data sharing and prescription transfers. In a health system, the patient profile may interface with the larger clinical information system in a health system to allow the pharmacist access to important disease state and monitoring information when filling medication orders.

Reports

As pharmacy systems have grown larger and more complex, managing patient and drug-related information in the larger computer database has become more important. The pharmacy information system allows pharmacists and administrators to generate reports that can assist with overall patient care and management of the pharmacy or institution. Key reports, which allow administrators to identify trends or problems that might otherwise be missed, include the following:

- Inventory activity

- Drug usage

- Overrides

- User access

- Controlled substances

- Drug diversion

For example, if a major drug–drug interaction warning is nearly always overridden, patients may be at risk of adverse events. Identifying high usage rates of a very expensive drug when an equal but more cost-effective option is available within a health system can help target an intervention that could lower system-wide costs.

Computerized Systems for Pharmacy Dispensing

Now that you have a better understanding of the big picture of pharmacy information systems and their importance, let’s look more closely at the individual computerized systems used within the dispensing process to increase accuracy and efficiency.

Pharmacists have been using computer technology for prescription ordering, processing, and dispensing since the late 1970s. Although computerized physician order entry and electronic prescribing are rapidly growing more prevalent, pharmacists and technicians are still closely tied to the prescription or medication order entry process.2,4,5 Computerized order entry screens (Figure 7-2) use codes for drug names and strengths as well as instructions for use. Although it may take time to become accustomed to these codes, they greatly speed the rate at which you can enter prescriptions into the system without having to type out everything in full.

Computer-related technology is also now used routinely to improve accuracy and efficiency of the dispensing processes, especially in health systems, mail-order pharmacies, high-volume community pharmacies, or pharmacies utilizing centralized fill procedures at a remote location. The types of computer-related technology in routine use include the following:

- Automated prescription-dispensing systems—For community pharmacies, automated prescription-dispensing systems fill one-half or more of the daily workload in the pharmacy department. The process begins when the technician enters an order into the prescription software system and the actual prescription is scanned into the system. Using drug products that have been placed into bins—usually by technicians—robotic-like devices interpret the prescription order, prepare a label, place medication into a vial or other container, and transfer the prescription label onto the container. The pharmacist then checks the entire process and uses computer-generated patient-counseling materials to make sure the patient knows how to take the medication properly.

- Automated cart-fill machines—A similar type of machine used in hospital and nursing home operations is the automated cart-fill machine. In institutions, medications are often transferred from the pharmacy to the patient-care areas using carts. These carts have drawers, called cassettes. Each cassette contains the medications ordered by the physician for one patient for a given period of time (usually 24 hours in a hospital, but up to 30 days for a long-term care facility such as a nursing home). The automated cart-fill machine picks the drugs that are on each patient’s computerized profile from medication bins filled by pharmacy technicians. It then places the correct number of medications into the patient’s cassette. These automated systems rely on bar codes to be certain that the right medication is being prepared based on each prescription order.

- Automated point-of-care dispensing machines—Another type of technology in use in institutions is the automated point-of-care dispensing machine, often called the Pyxis, after the company that markets it. These dispensing machines are placed in patient-care areas so nurses can obtain directly from them some of the medications needed for each patient. A common use for these point-of-care devices is storing controlled substances—that is, those medications that can be abused (see Chapter 3, Pharmacy Law and Regulation). Because controlled substances cannot be placed in unlocked cassettes on the carts (from which they could be easily diverted for personal use or for illegal sale on the street), point-of-care machines restrict access to medications and require the nurse to record the name of the patient who is to receive each dose.

- Robots for product delivery—Primarily in very large hospitals, automated devices that are just like robots seen in movies are used for delivering medications to patient-care areas. These machines roll through the halls, get on and off elevators, and talk to people that they sense nearby. On the nursing unit, they deliver patient medications to nurses, recording who accepted transfer of the drugs. The robots can be very useful in hospitals that do not have other, less expensive delivery mechanisms, such as pneumatic tube systems. Just as in drive-in banking centers, pneumatic tubes are used in many hospitals to bring medication orders to the pharmacy and to send medications to the patient-care areas.

As automated systems continue to develop, they will surely present more challenges and opportunities to pharmacists and technicians. Computerized technology will become more sophisticated and will start performing tasks that humans now do. Increasingly, the job of humans will be to program, manage, fill, and repair automated systems. As a pharmacy technician, you may find yourself becoming more of an information manager and computer technician in the years ahead.

Computerized Systems for Medication Therapy Management Activities

Just as information technology is an essential feature of pharmacy-dispensing processes, computers are increasingly important in medication therapy management (MTM) services. In several key areas, pharmacists are using technology to manage clinical tasks and information. Two needs of MTM services match perfectly with the capabilities of computer programs: documentation and billing.

Documentation involves recording information about the patient and the interventions made by the pharmacist and other pharmacy personnel. This record keeping is essential for two reasons. First, to be paid by third-party payers, the pharmacist must have a record of the work performed. Second, if something goes wrong and the patient later becomes ill or dies, the pharmacist will need information that can be presented in court to show that the interventions made were necessary and appropriate.

Billing, which is covered in more detail in Chapter 11, Pharmacy Billing and Reimbursement, is the process of obtaining payment from insurance companies, the government, or health plans. Pharmacy owners sign contracts with these third-party payers, and the contract requires the pharmacy to keep records of the prescriptions dispensed and other interventions made. The records must be made available to the third-party payer on demand so the payer can be sure the pharmacy has, in fact, done what it was paid for. These records are critically important to avoid contract cancellation or criminal charges that the pharmacy has defrauded the third-party payer.

For pharmaceutical care, many types of information are recorded in computer software programs:

- Care plans (what problems the pharmacist has found and how they are to be treated)

- Disease management (interventions unique to various diseases)

- Therapeutic outcomes (the effects of interventions on the patient’s clinical condition as well as quality of life)

- Progress notes (what the pharmacist observes in each visit with the patient)

- Billing information (when and how payment was requested)

If you are asked to enter pharmaceutical care information into the computer, you will need to complete training for the systems used in your workplace.

Computer-Related Issues in Pharmacy Practice

Information today is a very powerful—and valuable—commodity. But just as people are concerned about companies sharing or selling information about their credit card transactions, they are troubled to learn that their pharmacy provides information to outside parties. This practice has become a part of a broader discussion of confidentiality with respect to health care information. Confidentiality is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3, Pharmacy Law and Regulation, and Chapter 8, Interacting with Patients, but a brief mention is merited here with respect to computers.

The data available in pharmacy computer systems is of interest to several outside parties, but its confidentiality must be respected. If patients cannot share private information with their pharmacists without fear that other people or outside companies will learn about it, then they are not likely to tell the pharmacist everything necessary for pharmacists to provide quality pharmaceutical care. Pharmacies have sometimes encountered public outcry or lawsuits when they have engaged in the following practices:

- Using pharmaceutical industry grants to pay outside companies to send prescription refill reminders to patients.

- Providing names and addresses of patients who have had prescriptions filled for certain drugs to the manufacturers of those or competing drugs, and providing the names of prescribing physicians to manufacturers.

Conclusion

Pharmacy information and computer systems have become workhorses of the pharmacy to manage all the complex aspects of patient care in our health care system. Even so, you must never forget the “people” side of pharmacy practice. Everything you do is aimed at producing positive effects on people’s lives. In your role as a pharmacy technician, you will interact with patients—who are in all respects the reason the pharmacy was established and continues to operate—and with the health professionals who take care of these patients. In Chapter 8, let’s look at ways of communicating with and pleasing the important people you deal with every day.

For More Information

If you are preparing for a certification examination for pharmacy technicians and need more information about the topics discussed in this chapter, consider studying these sources of additional information:

- Fox BI, Thrower MR, Felkey BG. Building Core Competencies in Pharmacy Informatics. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2010.

- Snipe K. Automated systems. In: The Pharmacy Technician Skills-Building Manual. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2007:143–8. (Note: New edition due out in 2014.)

- References for this chapter.

REFERENCES

1. Biohealthmatics.com. Pharmacy information systems. Available at: http://www.biohealthmatics.com/technologies/his/pis.aspx. Accessed August 11, 2013.

2. Chaffee BW, Bonasso J. Strategies for pharmacy integration and pharmacy information system interfaces, part 1: history and pharmacy integration options. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004; 61:502–6.

3. Chaffee BW, Bonasso J. Strategies for pharmacy integration and pharmacy information system interfaces, part 2: scope of work and technical aspects of interfaces. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:506–14.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Benefits of electronic health records. Available at: http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/benefits-electronic-health-records-ehrs. Accessed August 11, 2013.

5. Odukoya OK, Chui MA. Relationship between e-prescriptions and community pharmacy workflow. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52: e168–74.

Pharmacy information systems are, simply put, the computer systems that the pharmacy uses to manage all the information required to care for patients.1 Although such systems may appear straightforward at first glance (see Figure 7-1), they accommodate some of the most important clinical, documentation, and communication functions in the pharmacy, such as

- Clinical screening for drug interactions

- Prescription order entry

- Prescription and inventory management

- Patient profiles

- Reports of medication use

- Interactions with other systems related to payment, regulatory compliance, and so on

These systems have led to many improvements in data management and patient safety, including faster processing of orders and prescriptions, reduced medication errors, and improved adherence to medication-use policies or drug formularies (see Chapter 13) within an institution.2,3 Table 7-1 includes some terminology related to pharmacy information systems and their most common functions, as described below.

Clinical Screening

When information is entered into the patient profile, the pharmacy information system stores the records and applies the information to future prescriptions filled in the pharmacy. The pharmacy computer screens a patient’s medication list, drug allergy information, current or former smoking or alcohol history, pregnancy status, age, weight, and much more information every time a new prescription or medication order is entered. Some pharmacy information systems also allow you to document previous medication adverse events or patient risk factors. When entering information into the computer, be complete and accurate to ensure that all data are correct and properly updated.

|

DEFINITION |

|

|

Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) |

Physicians or other providers enter medication orders directly into the computer system on the patient-care unit or floor instead of transmitting a written or verbal order to the pharmacy for order entry. |

|

Electronic medical record (EMR) |

An electronic or digital version of a patient’s chart that allows providers to track patient data, identify ongoing patient needs, monitor specific laboratory or other parameters over time, and handle many other components of a patient’s care within a single pharmacy or institution. |

|

Electronic health record (EHR) |

Similar to an EMR, but often provides additional information about the patient’s history outside of a single institution. In some cases, patients may have access to their EHR information when they see providers in different institutions or practices. |

|

Clinical information system |

A computerized pharmacy information system that also provides information on the clinical care of patients, such as electronic medication administration records, laboratory and other patient data, and diagnoses. |

|

Clinical decision support (CDS) |

Electronic tools to help pharmacists, physicians, and other providers or individuals involved in health care make informed decisions about treatment or other options. CDS systems may include drug-interaction alerts with alternative treatments, predetermined order sets for high-risk medications, links to clinical guidelines, and many other resources. |

|

Electronic prescribing (e-prescribing, e-Rx) |

Computer-based generation and transmission of a prescription directly from the prescriber, usually to an outpatient or mail-order pharmacy. In contrast to CPOE, which generally occurs within a single closed system, e-prescribing transmits a prescription electronically between separate systems (e.g., from the provider’s office to the pharmacy), taking the place of paper, faxes, or telephone orders. E-prescribing can reduce medication errors because it removes subjective factors such as illegible handwriting, but it may also introduce new types of errors, such as a prescriber selecting the wrong medication from a drop-down menu. |

Prescription Records and Management

At minimum, a patient’s prescription record will include basic information about their current and past prescriptions (Table 7-2). Although specific details depend on which computer system your pharmacy uses, nearly all pharmacy systems use prescription records in the dispensing process. Many also interface prescription records with inventory to verify if a specific product is in stock or even track which stage of dispensing any given prescription or medication order is currently in. As a technician, understanding the prescription records and management components of your pharmacy’s information system will be a key to your success in the pharmacy.

Inventory Management

With the number of drugs and pharmaceutical products on the market, it would be nearly impossible to keep track of pharmacy inventory (see Chapter 13) without computerized systems. Pharmacy computer systems are often used to maintain accurate counts of current inventory, display an alert when products go below a preset quantity, identify appropriate suppliers for product replacement, or automatically reorder products.

[/membership]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree