Summary by Robbie Bahl, MD, and Abigail J. Herron, DO

53

Based on “Principles of Addiction Medicine” Chapter by Richard D. Hurt, MD, FASAM, Jon O. Ebbert, MD, J. Taylor Hays, MD, and David D. McFadden, MD

Tobacco use disorder, like other addictive disorders, is a chronic relapsing and remitting medical condition. The efficient and rapid delivery of nicotine by cigarettes is a key factor in the development of tobacco dependence, and nicotine replacement products commonly used to treat tobacco dependence are relatively inefficient in delivering nicotine and deliver much lower concentrations much more slowly compared with cigarettes. Nicotine replacement products as well as other nonnicotine medications are indicated to treat tobacco dependence but have important limitations; thus, the clinician will need to use considerable skills to maximize their efficacy.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF TOBACCO DEPENDENCE

Nicotine has complex and wide-ranging effects on the central nervous system. Nicotine binds to and causes conformational changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are located in all areas of the human brain and, when stimulated, cause the release of dopamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, vasopressin, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, beta-endorphins, and other neurotransmitters. The mesolimbic dopamine system, important in pleasure and reward, and the locus caeruleus, important for cognitive function, contain high concentrations of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that exist in the mesolimbic dopamine system and locus caeruleus.

MEASURING NICOTINE EXPOSURE

One approach to the therapeutic use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is to determine the patient’s level of nicotine exposure and then provide a nicotine replacement dose approximating the dose the individual receives from smoking. Nicotine exposure can be quantified through the measurement of cotinine, which has a half-life of 18 to 20 hours and reflects nicotine exposure over 2 to 3 days versus venous nicotine concentrations, which reflect acute exposure. Anabasine is a tobacco alkaloid that is not a metabolic product of nicotine, which is present in the urine of tobacco users but not in the urine of patients using NRT, and can distinguish abstinent tobacco users who are using NRT from those who are continuing to use tobacco.

NICOTINE REPLACEMENT THERAPY

There are five FDA-approved nicotine replacement products: Gum, patches, and nasal spray are available over the counter, while the inhaler and lozenges are only available by prescription in the United States. A combination therapy of short-acting NRT (gum, lozenge, inhaler, or spray) with longer-acting medication such as the nicotine patch, bupropion, and/or varenicline has been shown to be beneficial.

Nicotine Gum

Both the 2- and 4-mg doses have been shown to be effective as monotherapy or in combination with other NRT. The higher dose is indicated for use in smokers with higher levels of physical dependence, such as those who smoke more than 20 cigarettes daily and smoke their first cigarette within 30 minutes of arising. The most common adverse effects of nicotine gum are nausea and indigestion, which can be minimized with the proper “chew-and-park” technique and avoiding the swallowing of saliva containing nicotine as it is released from the gum. Other adverse effects reported include gingival soreness and mouth ulcerations.

Nicotine Lozenge

The nicotine lozenge is available in 2- and 4-mg doses, with the latter for use in more dependent smokers. Although the method of delivery (transbuccal) is similar to that of nicotine gum, the lozenge is simpler to use and likely will demonstrate improved patient compliance. As with the other short-acting NRT products, it is most often used in combination with other NRT, bupropion, or varenicline

Nicotine Nasal Spray

Nicotine nasal spray delivers nicotine directly to the nasal mucosa and has been observed to be effective for achieving smoking abstinence as monotherapy. This method delivers nicotine more rapidly than do NRT delivery systems and has been shown to reduce withdrawal symptoms more quickly than does nicotine gum, due in part to the rapid absorption of nicotine from the nasal mucosa. The most common adverse side effects are rhinorrhea, nasal and throat irritation, watery eyes, and sneezing, which decrease significantly within the first week of use independent of dose.

Nicotine Inhaler

Although the device is called an inhaler, very little of the nicotine vapor actually reaches the lungs, even with deep inhalations. Instead, it delivers nicotine in vapor form that is absorbed across the oral mucosa. Each cartridge yields about 80 puffs, delivering about 4 mg of nicotine and lasts for approximately 20 minutes of active use. It has been shown to be effective as monotherapy with use of more than six cartridges per day. Adverse effects are generally mild and include mouth or throat irritations.

Nicotine Patch

Nicotine patch therapy delivers a steady dose of nicotine for up to 24 hours after a single application. Nicotine patches are available in doses of 7, 14, and 21 mg. Nicotine patches have repeatedly been shown to be effective when compared with placebo in achieving abstinence from smoking.

Patch doses up to 21 mg/day achieve a serum cotinine level about half of that achieved through smoking. Because of concerns about underdosing patients with standard patch doses, studies have been conducted assessing the efficacy of higher doses. High-dose nicotine patch therapy has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in patients who smoke more than 20 cigarettes per day, for those who previously failed single-dose patch therapy, or for those whose nicotine withdrawal symptoms are not relieved sufficiently with standard therapy. While the 2008 United States Public Health Service Guideline Panel concluded that high-dose nicotine patch therapy did not appear to produce benefit above and beyond that of standard-dose nicotine patch therapy, the panel observed that if the patient is severely addicted, the clinician may consider higher than the FDA-recommended dose and that higher doses have been shown to be effective in highly dependent smokers. Subsequent to the guideline publication, a Cochrane Review showed a small improvement in smoking abstinence outcomes with higher nicotine patch doses.

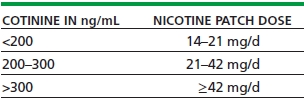

By employing the concept of therapeutic drug monitoring, clinicians can use serum cotinine concentrations to tailor the nicotine replacement dose so that it approaches 100% replacement. Table 53-1 shows the recommended initial dosing of nicotine patch therapy based on serum cotinine concentrations. Higher percentage replacement has been shown to reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms, but the efficacy for long-term smoking abstinence of such an approach has not been completely established. If serum cotinine testing is not available, the replacement dose can be estimated based on the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Table 53-2 shows the recommended initial dosing of nicotine patch therapy based on the number of cigarettes smoked per day, which has been shown to roughly correlate with the cotinine concentrations shown in Table 53-1.

TABLE 53-1. NICOTINE PATCH DOSE BASED ON BASELINE (WHILE SMOKING) BLOOD COTININE CONCENTRATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree