Chapter 6 Pharmacogenetics

The Promise of Personalized Medicine

Take the example of a new anticancer drug, considered to be a breakthrough therapy for lung cancer. As a collection of diseases rooted in genetics, cancer has become one of the clearest examples of the potential for pharmacogenomics in predicting pharmacodynamics of a given drug in a given patient, as outlined in the following example.

Take the example of a new anticancer drug, considered to be a breakthrough therapy for lung cancer. As a collection of diseases rooted in genetics, cancer has become one of the clearest examples of the potential for pharmacogenomics in predicting pharmacodynamics of a given drug in a given patient, as outlined in the following example. An anticancer drug may be considered successful if 10% to 20% of patients respond to it. From a clinician’s perspective and from the perspective of those 10% to 20% of patients, this is a success, but from a health economist’s perspective, a $30,000-per-year drug that fails in 80% to 90% of patients is not cost-effective. If the annual cost for a new anticancer drug is going to be around $30,000 to $60,000, the only way to make these promising new drugs cost-effective is to administer them to only the 10% to 20% of patients who will benefit from them.

An anticancer drug may be considered successful if 10% to 20% of patients respond to it. From a clinician’s perspective and from the perspective of those 10% to 20% of patients, this is a success, but from a health economist’s perspective, a $30,000-per-year drug that fails in 80% to 90% of patients is not cost-effective. If the annual cost for a new anticancer drug is going to be around $30,000 to $60,000, the only way to make these promising new drugs cost-effective is to administer them to only the 10% to 20% of patients who will benefit from them.Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics

Pharmacogenomics takes a broader view of the influence of an individual’s entire genome on his or her response to drug therapy.

Pharmacogenomics takes a broader view of the influence of an individual’s entire genome on his or her response to drug therapy.One can consider pharmacogenetics to be the original term for this field, coined in the days when tools such as microarrays did not exist and the human genome had not been mapped. In those early days it seemed unlikely or impossible that an entire genome could be analyzed in an efficient enough manner to become a useful tool in everyday medicine. Now that we have the means and the knowledge to envision a genome-wide approach to everyday prescribing, the term pharmacogenomics is often used to refer to this field. Table 6-1 lists some of the terms commonly used in pharmacogenetics.

TABLE 6-1 Definitions of Some Common Terms Used in Pharmacogenetics

| Gene | A sequence of nucleotides that corresponds to a sequence of amino acids in an entire protein or part of a protein. Genes are typically found at a specific location on a chromosome. |

| Genome | The full genetic complement of an individual. |

| Allele | Any of the alternative forms of a gene at a particular locus. These alternative forms may or may not result in different phenotypes. |

| Null allele | A mutation in a gene that leads to a loss of function. Either the gene is not expressed at all (i.e., no protein or RNA) or the product is not functional. |

| Polymorphism | Variation in DNA sequence present at a specific locus within a population. |

| Genotype | The genetic makeup of an individual. |

| Phenotype | The observable physical or biochemical characteristics of an organism. Determined by genotype and environment. |

| Monogenic | Related to or controlled by a single gene |

| Polygenic | Related to or controlled by multiple genes. A polygenic trait is a phenotype that is determined by multiple genes rather than a single gene (monogenic). |

| Germ line | Cellular lineage; genetic information that is passed from one generation to the next. |

| Haplotype | A group of alleles of different genes on a single chromosome that are so closely linked that they are inherited as a unit. |

| Somatic cell | Any cell in the body, with the exception of those involved in reproduction. |

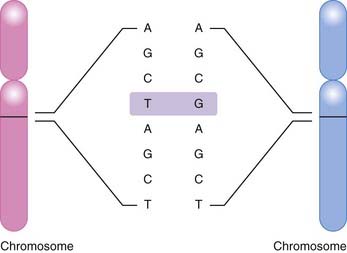

The most common basis for genetic variation, and thus the basis for a pharmacogenomic approach to drug therapy, is the single nucleotide polymorphism, or SNP (Figure 6-1). An SNP occurs when a single nucleotide is exchanged for another at a point in an individual’s genome. It is estimated that the human genome consists of approximately 3 billion nucleotides, which in specific combinations form 25,000 to 40,000 genes and encode approximately 100,000 proteins (at last count). SNPs that occur in coding regions of the genome have the potential to influence protein expression by altering an amino acid within the protein.

Nonsynonymous coding SNPs (cSNPs) or missense SNPs change the identity of an amino acid. Substitution of this amino acid may change the structure or function of the protein.

Nonsynonymous coding SNPs (cSNPs) or missense SNPs change the identity of an amino acid. Substitution of this amino acid may change the structure or function of the protein. Synonymous coding SNPs or sense SNPs do not change the identity of an amino acid and are not likely to affect the structure or function of the protein.

Synonymous coding SNPs or sense SNPs do not change the identity of an amino acid and are not likely to affect the structure or function of the protein. Nonsense mutations are SNPs that lead to a stop codon. A stop codon will halt translation of nucleotides into a protein.

Nonsense mutations are SNPs that lead to a stop codon. A stop codon will halt translation of nucleotides into a protein.Pharmacokinetics

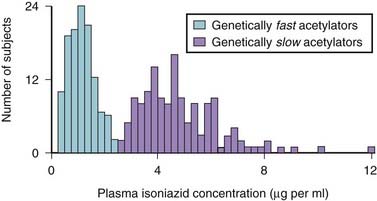

A classic example occurred with the antituberculosis drug isoniazid (Figure 6-2). Isoniazid is acetylated (metabolized) by N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), and it was observed that some patients metabolized this drug slowly (i.e., were slow metabolizers), whereas others were rapid metabolizers.

A classic example occurred with the antituberculosis drug isoniazid (Figure 6-2). Isoniazid is acetylated (metabolized) by N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), and it was observed that some patients metabolized this drug slowly (i.e., were slow metabolizers), whereas others were rapid metabolizers. The clinical consequence is that rapid metabolizers would have low plasma levels of the drug, increasing the potential for therapeutic failure, whereas slow metabolizers were predisposed to toxicities associated with the drug.

The clinical consequence is that rapid metabolizers would have low plasma levels of the drug, increasing the potential for therapeutic failure, whereas slow metabolizers were predisposed to toxicities associated with the drug. This wide variation in response to isoniazid led researchers to speculate that genetics might be playing a role. Isoniazid became one of the first drugs to be identified as having a genetic component to its pharmacologic actions.

This wide variation in response to isoniazid led researchers to speculate that genetics might be playing a role. Isoniazid became one of the first drugs to be identified as having a genetic component to its pharmacologic actions.