Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Imaging and Intervention

Brian S. Geller

DEFINITION

Cholangiography is the term used to describe the evaluation of the biliary system by fluoroscopy after injection of radiopaque material (contrast). The introduction of contrast can be performed either in a retrograde (via endoscope) or an antegrade manner.

The antegrade introduction of contrast requires percutaneous transhepatic access into the biliary system. A percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram (PTC) is commonly performed when a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were inconclusive or unable to be performed.

When an obstruction of the biliary system cannot be managed by endoscopic means, a drainage catheter can be placed. This procedure is known as percutaneous transhepatic drainage (PTHD).

Numerous biliary pathologies are routinely managed by the percutaneous route: stone/debris removal, stricture dilation, long-term catheter drainage, and metallic stent placement.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A PTC is an invasive procedure and as such, non- or less invasive imaging of the biliary system should be attempted; these include MRCP and ERCP. If these options fail to make the diagnosis or cannot be performed due to the patient’s anatomy, then a PTC should be performed.

Indications for cholangiography include biliary stenosis or obstruction, or bile leak. The underlying pathology includes stones, malignancy, infection, inflammation, fibrosis/scarring, and iatrogenic complications.

Patients with biliary obstruction or moderate- to high-grade stenosis usually present jaundice with elevations of the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and total bilirubin (TB). ALP is a more sensitive identifier of biliary pathology and typically precedes elevation of the TB. If the bile has become infected, the patient can also present with fever, leukocytosis, and sepsis. Bile leaks present with abdominal pain (secondary to a chemical peritonitis), fever, leukocytosis, nausea/vomiting, and jaundice.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Ultrasound (US) or computed tomography (CT) can be used to diagnose biliary dilation. Note: Posttransplant livers do not normally have dilated ducts when obstructed.

First-line imaging of the biliary system is routinely a US. This modality is readily available, inexpensive, and uses no radiation. US is optimal for detection of biliary dilation, gallbladder pathology, and ascites. It also serves a role in the identification and characterization of hepatic masses and Doppler mode provides information regarding potential vascular pathology (FIG 1).

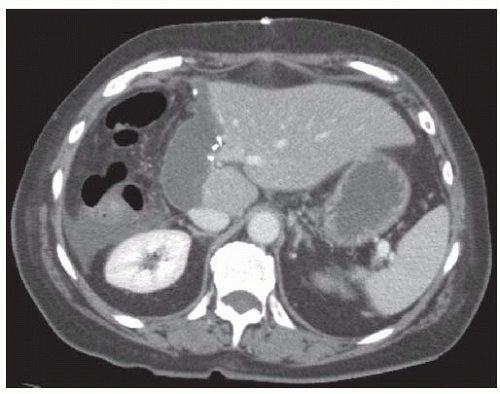

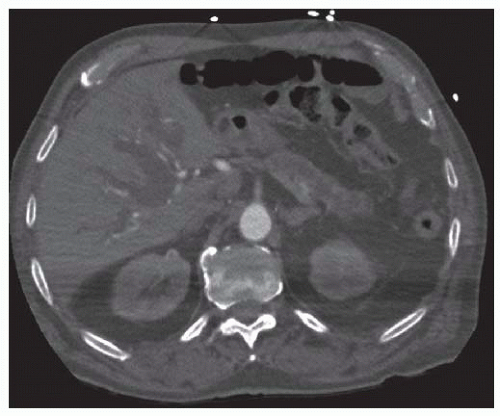

When a broader view of the abdomen is needed, a CT scan can be performed. Intravenous (IV) contrast is routinely administered, and due to the nature of the exam, the patient will be exposed to radiation (equivalent of ∽100 chest x-rays) (FIGS 2 and 3).

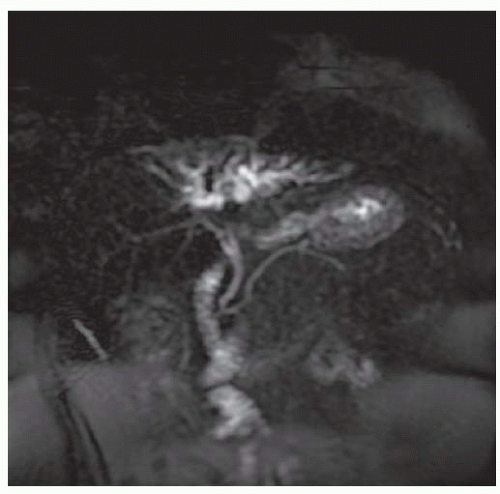

MRCP can also be performed to evaluate the biliary system and surrounding liver parenchyma. Note that the nature of the magnetic resonance (MR) protocol that is required to optimally visualize, the biliary system, does not optimally assess surrounding structures, thus limiting the evaluation of nonbiliary pathology (FIG 4).

FIG 2 • Axial CT image with marked intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation and pancreatic ductal dilation.

FIG 4 • Coronal image from MRCP demonstrating dilation of the right anterior and left hepatic ducts. The right posterior, common hepatic, and pancreatic ducts are of normal caliber.

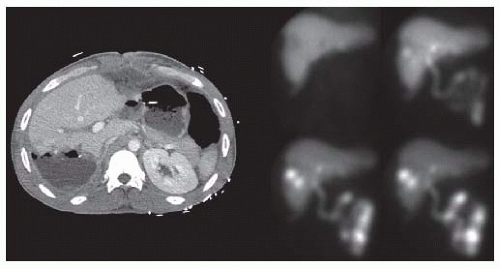

When evaluating for a bile leak, cholescintigraphy (also known as a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid [HIDA] or diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid [DISIDA] scan) can be performed. The radiopharmaceutical is taken up by the liver and excreted into the bile. When the tracer is seen accumulating outside of the liver, or in intrahepatic cavities, the diagnosis of leak can be confirmed (FIG 5).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preprocedure Planning

All related imaging to the patient’s condition should be reviewed. A PTC/PTHD can be performed either under conscious sedation or with general anesthesia (preferred). Thus, the patient ideally will be nil per os for at least 6 hours prior to the procedure.

For any procedure that manipulates the biliary system, there is an increased risk of septicemia and endotoxemia. The patient should receive antibiotics within 1 hour of start time. The mix of gastrointestinal flora should guide antibiotic choice (gram negatives and anaerobes). At our institution, piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g is routinely used. In patients who are penicillin allergic, ciprofloxacin 400 mg and metronidazole 500 mg are given.

Unless the left-sided ducts are unilaterally dilated, a rightsided approach is routinely used, as this will drain a larger portion of the liver and will decrease radiation exposure to the interventionalist.

Positioning

Biliary procedures are performed with the patient in the supine position, arms at the side.

TECHNIQUES

PERCUTANEOUS TRANSHEPATIC CHOLANGIOGRAPHY

Immediate Preprocedure

The patient’s abdomen should be cleaned and prepped from the nipple line to the left midaxillary line to 5 cm below the umbilicus and beyond the right posterior axillary line.

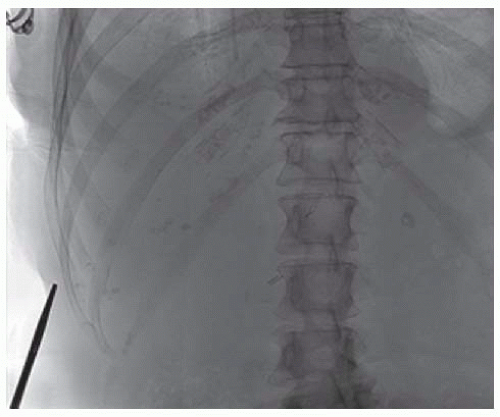

When right-sided access is warranted, a hemostat should be placed at the right midaxillary line at the selected access site during deep inspiration (FIG 6). This is used to verify that the entrance site is below the greatest diaphragmatic excursion. Access above this mark should not be attempted as it exposes the patient to the risk of violating the pleura, resulting in pneumothorax or biliary-pleural fistula.

Local anesthetic should be used and a small incision (2 to 3 mm) made to facilitate needle passage.

Duct Cannulation

Duct cannulation can be performed with a 15-cm, 21-or 22-gauge Chiba needle. These needles are relatively small (thereby reducing bleeding risk) and can accept a 0.018-in wire.

When left-sided access is required, US is routinely used to localize a relatively superficial duct. The duct is then cannulated under direct US guidance.

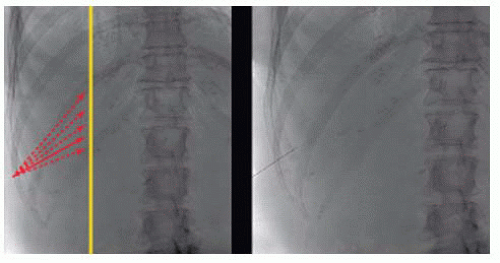

Due to the overlying ribs, right-sided access is usually accomplished with a “blind” technique, which can either be subclassified into an antegrade or retrograde approach.

When using the retrograde approach, the Chiba needle is advanced from the liver margin to the midaxillary line. The stylet is removed, and under fluoroscopy, a small amount of dilute contrast is injected as the needle is pulled back.

When using the antegrade approach, the stylet is removed from the Chiba needle, and under fluoroscopic guidance, the needle is advanced while injecting dilute contrast until reaching the midclavicular line.

Regardless of approach, multiple passes through the liver at different obliquities (cranial-caudal and anterior-posterior) are often required before a duct is cannulated (FIG 7). The technical challenge and number of passes required for successful cannulation is directly related to the extent of intrahepatic biliary dilation. This is particularly problematic in the setting of bile duct injury with a biliary tree that is fully decompressed into the peritoneal space.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree