CHAPTER 80 Pelvic girdle, gluteal region and thigh

The pelvic girdle consists of the paired hip bones (each consisting of the ilium, ischium and pubis) and a single sacrum. The two pubic bones articulate anteriorly at the pubic symphysis and the sacrum articulates posteriorly with the two iliac bones: however, the bones are virtually incapable of independent movement except in the female during parturition. The pelvic girdle is massively constructed and serves as a weightbearing and protective structure, as an attachment for trunk and limb muscles, and as the skeletal framework of a birth canal capable of accommodating a large-headed fetus.

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUES

SKIN

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

Thigh

The skin of the thigh distal to the inguinal ligament and gluteal fold is supplied mainly by branches of the femoral and profunda femoris arteries. There is some contribution from the obturator, inferior gluteal and popliteal arteries and from direct cutaneous, musculocutaneous and fasciocutaneous vessels. For further details consult Cormack & Lamberty (1994).

SOFT TISSUE

Fascia

Deep fascia

Fascia lata

Iliotibial tract

Over the flattened lateral surface of the thigh, the fascia lata thickens to form a strong band, the iliotibial tract. The upper end of the tract splits into two layers, where it encloses and anchors tensor fasciae latae and receives, posteriorly, most of the tendon of gluteus maximus. The superficial layer ascends lateral to tensor fasciae latae to the iliac crest; the deeper layer passes up and medially, deep to the muscle, and blends with the lateral part of the capsule of the hip joint. Distally, the iliotibial tract is attached to a smooth, triangular facet (Gerdy’s tubercle) on the anterolateral aspect of the lateral condyle of the tibia where it is superficial to, and blends with, an aponeurotic expansion from vastus lateralis. When the knee is extended against resistance it stands out as a strong, visible ridge on the anterolateral aspect of the thigh and knee.

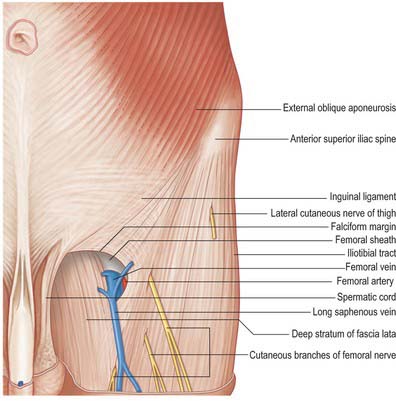

Saphenous opening

The saphenous opening is an aperture in the deep fascia, inferolateral to the medial end of the inguinal ligament, which allows passage to the long saphenous vein and other smaller vessels (Fig. 80.1). The cribriform fascia, which is pierced by these structures, fills in the aperture and must be removed to reveal it. Adjacent subsidiary openings may exist to transmit venous tributaries. In the adult the approximate centre of the opening is 3 cm lateral to a point just distal to the pubic tubercle. The length and width of the opening vary considerably. The fascia lata in this part of the thigh displays superficial and deep strata (not to be confused with the superficial and deep layers of the superficial fascia described above). They lie, respectively, anterior and posterior to the femoral sheath; with the saphenous opening situated where the two layers are in continuity. This serves to explain the somewhat oblique and spiral configuration of the saphenous opening.

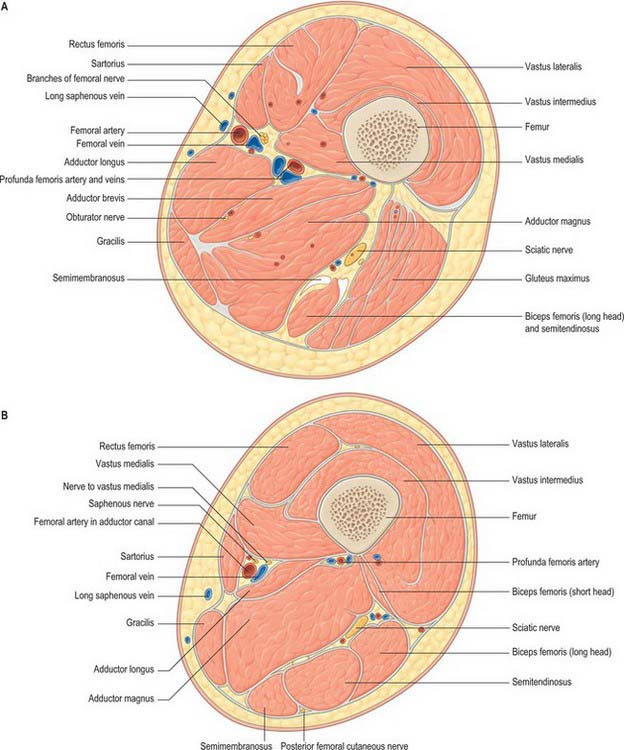

Fascial compartments

There are three functional groups of muscle in the thigh, namely, anterior (extensor), posterior (flexor) and medial (adductor). The anterior and posterior groups occupy separate osteofascial compartments that are limited peripherally by the fascia lata and separated from each other by the femur and the medial and lateral intermuscular septa (Fig. 80.2). The adductor muscles, though distinct in terms of function and innervation, do not possess a separate compartment limited by fascial planes. Nevertheless it is customary to speak of three compartments: anterior, posterior and medial. The muscles of the three compartments are described below. Adductor magnus, adductor longus and pectineus could each be considered to be constituents of two compartments, i.e. adductor magnus in the posterior and the medial compartments, and adductor longus and pectineus in the anterior and the medial compartments.

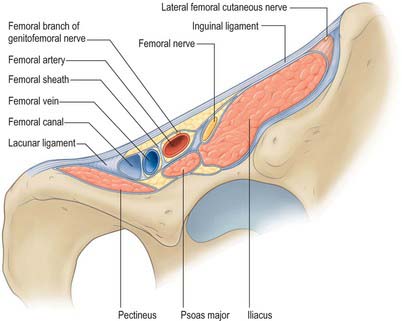

Femoral sheath

The femoral sheath is a funnel-shaped distal prolongation of extraperitoneal fascia, formed of transversalis fascia anterior to the femoral vessels, and of the iliac fascia posteriorly (Fig. 80.3). It is wider proximally and its tapered distal end fuses with the vascular adventitia 3 or 4 cm distal to the inguinal ligament. At birth the sheath is shorter; it elongates when extension at the hips becomes habitual. The femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve perforates its lateral wall. The medial wall slopes laterally and is pierced by the long (great) saphenous vein and lymphatic vessels. Like the carotid sheath, the femoral sheath encloses a mass of connective tissue in which the vessels are embedded. Three compartments are described: a lateral one containing the femoral artery, an intermediate one for the femoral vein, and a medial compartment, the femoral canal, which contains lymph vessels and an occasional lymph node embedded in areolar tissue. The presence of this canal allows the femoral vein to distend. The canal is conical and approximately 1.25 cm in length. Its proximal (wider) end, termed the femoral ring, is bounded in front by the inguinal ligament, behind by pectineus and its fascia and the pectineal ligament, medially by the crescentic, lateral edge of the lacunar ligament and laterally by the femoral vein. The spermatic cord, or the round ligament of the uterus, is just above its anterior margin, while the inferior epigastric vessels are near its anterolateral rim. It is larger in women than in men: this is due partly to the relatively greater width of the female pelvis and partly to the smaller size of the femoral vessels in women. The ring is filled by condensed extraperitoneal tissue, the femoral septum, which is covered on its proximal aspect by the parietal peritoneum. The femoral septum is traversed by numerous lymph vessels that connect the deep inguinal to the external iliac lymph nodes.

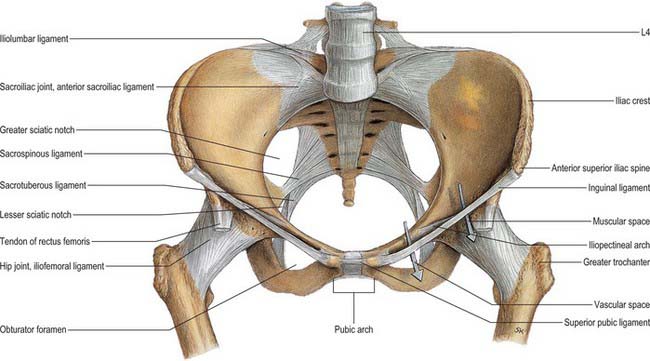

Iliac fascia

The iliac part is connected laterally to the whole of the inner lip of the iliac crest and medially to the pelvic brim, where it blends with the periosteum. It is attached to the iliopubic ramus, where it receives a slip from the tendon of psoas minor, when that muscle is present. The external iliac vessels are anterior to the fascia but the branches of the lumbar plexus are posterior. The fascia is separated from the peritoneum by loose extraperitoneal tissue. Lateral to the femoral vessels, the iliac fascia is continuous with the posterior margin of the inguinal ligament and the transversalis fascia. Medially it passes behind the femoral vessels to become the pectineal fascia, attached to the pecten pubis. At the junction of its lateral and medial parts it is attached to the iliopubic ramus and the capsule of the hip joint. It thus forms a septum between the inguinal ligament and the hip bone, dividing the space here into a lateral part, the muscular space, containing psoas major, iliacus and the femoral nerve, and a medial part, the vascular space, transmitting the femoral vessels (Fig. 80.3). The iliac fascia continues downward to form the posterior wall of the femoral sheath.

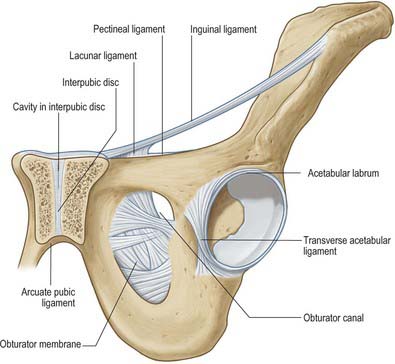

Obturator membrane

The obturator membrane (Fig. 80.4) is a thin aponeurosis that closes (obturates) most of the obturator foramen, leaving a superolateral aperture, the obturator canal, through which the obturator vessels and nerve leave the pelvis and enter the thigh. The membrane is attached to the sharp margin of the obturator foramen except at its inferolateral angle, where it is fixed to the pelvic surface of the ischial ramus, i.e. internal to the foramen. Its fibres are arranged mainly transversely in interlacing bundles; the uppermost bundle, which is attached to the obturator tubercles, completes the obturator canal. The outer and inner surfaces of the obturator membrane provide attachment for the obturator externus and internus respectively. Some fibres of the pubofemoral ligament of the hip joint are attached to the outer surface.

BONE

HIP BONE

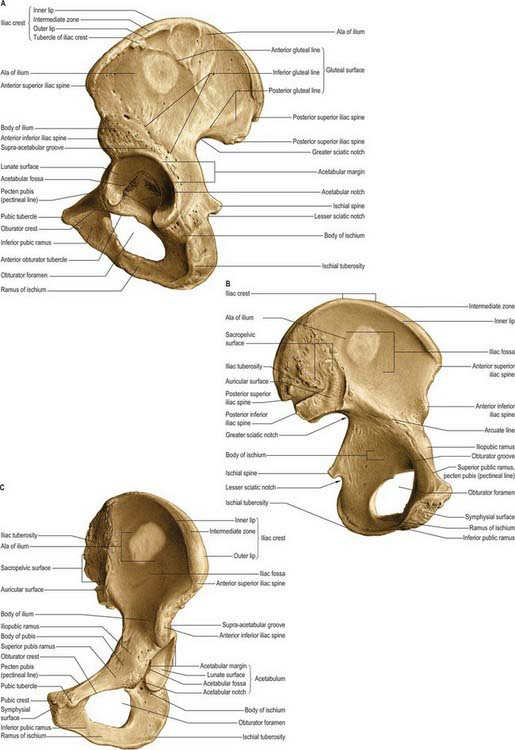

The hip bone is large, irregular, constricted centrally and expanded above and below (Fig. 80.5A,B). Its lateral surface has a deep, cup-shaped acetabulum, articulating with the femoral head, anteroinferior to which is the large, oval or triangular obturator foramen. Above the acetabulum the bone widens into an undulant plate surmounted by a sinuously curved iliac crest.

Fig. 80.5 Left hip bone. A, Outer aspect. B, Inner aspect. C, Anterosuperior view.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

Acetabulum

The acetabulum (Fig. 80.5A,C) is an approximately hemispherical cavity situated about the centre of the lateral aspect of the hip bone. It faces anteroinferiorly and is circumscribed by an irregular margin deficient inferiorly at the acetabular notch. The acetabular fossa forms the central floor and is rough and non-articular. The articular lunate surface is widest above (the ‘dome’), where weight is transmitted to the femur. Consequently, fractures through this region tend to be associated with unsatisfactory outcomes. All three components of the hip bone contribute to the acetabulum, although unequally. The pubis forms the anterosuperior fifth of the articular surface, the ischium forms the floor of the fossa and rather more than the posteroinferior two-fifths of the articular surface, and the ilium forms the remainder. Occasionally a linear defect may be seen to cross the acetabular surface from the superior border to the acetabular fossa This does not correspond to any junction between the main morphological parts of the hip bone.

Structure

The thicker parts of the hip bone are trabecular, encased by two layers of compact bone, while the thinner parts, as in the acetabulum and central iliac fossa, are often translucent and consist of a single lamina of compact bone. In the upper acetabulum and along the arcuate line, i.e. the route of weight transmission from the sacrum to the femur, the amount of compact bone is increased and the subjacent trabecular bone displays two sets of pressure lamellae. These start together near the upper auricular surface and diverge to meet two strong buttresses of compact bone, from which two similar sets of lamellar arches start and converge on the acetabulum. The anterior part of the iliac crest has been much studied with regard to distribution of cortical and trabecular bone. For a survey of these studies consult Whitehouse (1977). Additionally, Whitehouse’s observations, based on scanning electron micrography, indicate that the cortical bone is very porous, being only 75% bone, decreasing to 35% near the anterior superior iliac spine. Denser cortical bone starts at the margins of the crest and thickens rapidly below it on both aspects of the iliac blade.

Studies of the internal stresses within the hip bone have revealed a pattern of trabeculae that corresponds well with the theoretically expected patterns of stress trajectories (Holm 1980). These patterns are considerably more complex than in any other major bone. Stresses are higher in the acetabular than in the iliac region. In the ilium, the pelvic surface is subjected to considerably less stress than is the gluteal surface.

Vascular supply

In the infant, nutrient arteries are clearly demonstrable for each component of the hip bone. Each nutrient artery branches in fan-like fashion within its bone of supply (Crock 1996). Later, a periosteal arterial network develops, with contributions from numerous local arteries (see under individual bones).

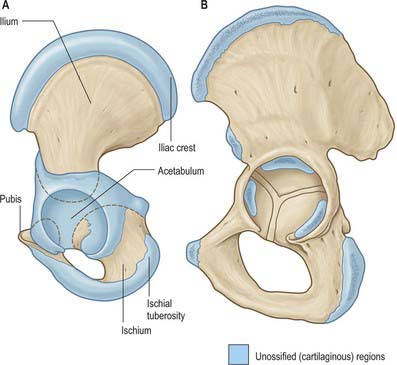

Ossification

Ossification (Figs 80.6, 80.7) is by three primary centres, one each for the ilium, ischium and pubis. The iliac centre appears above the greater sciatic notch prenatally at about the ninth week; the ischial centre in its body in the fourth month, and the pubic centre in its superior ramus between the fourth and fifth months. At birth the whole iliac crest, the acetabular floor and inferior margin are cartilaginous. Gradual ossification of the three components of the acetabulum results in a triradiate cartilaginous stem extending medially to the pelvic surface as a Y-shaped epiphysial plate between the ilium, ischium and pubis, and including the anterior inferior iliac spine. Cartilage along the inferior margin also covers the ischial tuberosity, forms conjoined ischial and pubic rami, and continues to the pubic symphysial surface and along the pubic crest to its tubercle.

Between the ages of 8 and 9 years three major centres of ossification appear in the acetabular cartilage. The largest appears in the anterior wall of the acetabulum and fuses with the pubis, the second in the iliac acetabular cartilage superiorly, fusing with the ilium, and the third in the ischial acetabular cartilage posteriorly, fusing with the ischium. At puberty these epiphyses expand towards the periphery of the acetabulum and contribute to its depth (Ponseti 1978). Fusion between the three bones within the acetabulum occurs between the 16th and 18th years. Delaere et al (1992) have suggested that ossification of the ilium is similar to that of a long bone, possessing three cartilaginous epiphyses and one cartilaginous process, although it tends to undergo osteoclastic resorption comparable with that of cranial bones. During development the acetabulum increases in breadth at a faster rate than it does in depth.

Pubis

Topography

The pubis (Figs 80.5, 80.6) is the ventral part of the hip bone and forms a median cartilaginous pubic symphysis with its fellow. The body of the pubis occupies the anteromedial part of the bone, and from the body a superior ramus passes up and back to the acetabulum and an inferior ramus passes back, down and laterally to join the ischial ramus inferomedial to the obturator foramen.

Superior pubic ramus

The superior pubic ramus passes upwards, backwards and laterally from the body, superolateral to the obturator foramen, to reach the acetabulum. It is triangular in section and has three surfaces and borders. Its anterior, pectineal surface, tilted slightly up, is triangular in outline and extends from the pubic tubercle to the iliopubic ramus. It is bounded in front by the rounded obturator crest and behind by the sharp pecten pubis (pectineal line) which, with the crest, is the pubic part of the linea terminalis (i.e. anterior part of the pelvic brim). The posterosuperior, pelvic surface, medially inclined, is smooth and narrows into the posterior surface of the body, which is bounded above by the pecten pubis and below by a sharp inferior border. The obturator surface, directed down and back, is crossed by the obturator groove sloping down and forwards. Its anterior limit is the obturator crest and its posterior limit is the inferior border.

Ilium

Topography

The ilium has upper and lower parts and three surfaces (Figs 80.5, 80.6). The smaller, lower part forms a little less than the upper two-fifths of the acetabulum. The upper part is much expanded, and has gluteal, sacropelvic and iliac (internal) surfaces. The posterolateral gluteal surface is an extensive rough area; the anteromedial iliac fossa is smooth and concave; the sacropelvic surface is medial and posteroinferior to the fossa, from which it is separated by the medial border.

Gluteal surface

The gluteal surface, facing inferiorly in its posterior part and laterally and slightly downwards in front, is bounded above by the iliac crest, below by the upper acetabular border and by the anterior and posterior borders. It is rough and curved, convex in front, concave behind, and marked by three gluteal lines. The posterior gluteal line is shortest, descending from the external lip of the crest approximately 5 cm in front of its posterior limit and ending in front of the posterior inferior iliac spine. Above, it is usually distinct, but inferiorly it is ill-defined and frequently absent. The anterior gluteal line, the longest, begins near the midpoint of the superior margin of the greater sciatic notch and ascends forwards into the outer lip of the crest, a little anterior to its tubercle. The inferior gluteal line, seldom well-marked, begins posterosuperior to the anterior inferior iliac spine, curving posteroinferiorly to end near the apex of the greater sciatic notch. Between the inferior gluteal line and the acetabular margin is a rough, shallow groove. Behind the acetabulum the lower gluteal surface is continuous with the posterior ischial surface, the conjunction marked by a low elevation.

Sacropelvic surface

The sacropelvic surface, the posteroinferior part of the medial iliac surface, is bounded posteroinferiorly by the posterior border, anterosuperiorly by the medial border, posterosuperiorly by the iliac crest and anteroinferiorly by the line of fusion of the ilium and ischium. It is divided into iliac tuberosity, auricular and pelvic surfaces. The iliac tuberosity, a large, rough area below the dorsal segment of the iliac crest, shows cranial and caudal areas separated by an oblique ridge and connected to the sacrum by the interosseous sacroiliac ligament. The sacropelvic surface gives attachment to the posterior sacroiliac ligaments and, behind the auricular surface, to the interosseous sacroiliac ligament. The iliolumbar ligament is attached to its anterior part. The auricular surface, immediately anteroinferior to the tuberosity, articulates with the lateral sacral mass. Shaped like an ear, its widest part is anterosuperior, its ‘lobule’ posteroinferior and on the medial aspect of the posterior inferior spine. Its edges are well defined, but the surface, though articular, is rough and irregular. It articulates with the sacrum and is reciprocally shaped. The anterior sacroiliac ligament is attached to its sharp anterior and inferior borders. The narrow part of the pelvic surface, between the auricular surface and the upper rim of the greater sciatic notch, often shows a rough preauricular sulcus (that is usually better defined in females) for the lower fibres of the anterior sacroiliac ligament. For the reliability of this feature as a sex discriminant, refer to Finnegan (1978) and Brothwell & Pollard (2001). The pelvic surface is anteroinferior to the acutely recurved part of the auricular surface, and contributes to the lateral wall of the lesser pelvis. Its upper part, facing down, is between the auricular surface and the upper limb of the greater sciatic notch. Its lower part faces medially and is separated from the iliac fossa by the arcuate line. Anteroinferiorly it extends to the line of union between the ilium and ischium. Though usually obliterated, it passes from the depth of the acetabulum to approximately the middle of the inferior limb of the greater sciatic notch.

Ischium

Topography

The ischium, the inferoposterior part of the hip bone, has a body and ramus. The body has upper and lower ends and femoral, posterior and pelvic surfaces (Figs 80.5, 80.6). Above, it forms the posteroinferior part of the acetabulum; below, its ramus ascends anteromedially at an acute angle to meet the inferior pubic ramus, thereby completing the boundary of the obturator foramen. The ischiofemoral ligament is attached to the lateral border below the acetabulum.

Ischial ramus

The ischial ramus has anteroinferior and posterior surfaces continuous with the corresponding surfaces of the inferior pubic ramus: the anteroinferior surface is roughened by the attachment of the medial femoral muscles. The smooth posterior surface is partly divided into perineal and pelvic areas, like the inferior pubic ramus. The upper border completes the obturator foramen; the rough lower border, together with the medial border of the inferior pubic ramus, contributes to the pubic arch. The fascia overlying the superficial perineal muscles is attached below the ridge between the perineal and pelvic areas of the posterior surface of the ischial ramus. Above the ridge areas give attachment to the crus of the penis or clitoris and the sphincter urethrae. The lower border of the ramus provides an attachment for the fascia lata and a membranous layer of the superficial perineal fascia.

Ischial spine

The ischial spine projects downwards and a little medially (Fig. 80.8). The sacrospinous ligament is attached to its margins, separating the greater from the lesser sciatic foramen. The ligament is crossed posteriorly by the internal pudendal vessels, pudendal nerve and the nerve to obturator internus.

SKELETAL PELVIS AS A WHOLE

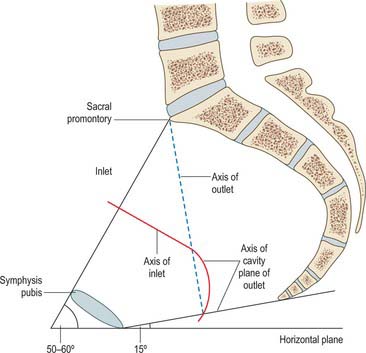

Pelvic axes and inclination

The axis of the superior pelvic aperture traverses its centre at right angles to its plane, directed down and backwards (Fig. 80.9). When prolonged (projected) it passes through the umbilicus and midcoccyx. An axis is similarly established for the inferior aperture: projected upwards it impinges on the sacral promontory. Axes can likewise be constructed for any plane, and one for the whole cavity is a concatenation of an infinite series of such lines (Fig. 80.9). The fetal head, however, descends in the axis of the inlet as far as the level of the ischial spines; it is then directed forwards into the axis of the vagina at right angles to that axis. The form of this pelvic axis and the disparity in depth between the anterior and posterior contours of the cavity are prime factors in the mechanism of fetal transit in the pelvic canal.

In the standing position the pelvic canal curves obliquely backwards relative to the trunk and abdominal cavity. The whole pelvis is tilted forwards, the plane of the pelvic brim making an angle of 50–60° with the horizontal. The plane of the pelvic outlet is tilted to about 15°. Strictly, the pelvic outlet has two planes, an anterior passing backwards from the pubic symphysis and a posterior passing forwards from the coccyx, both descending to meet at the intertuberous line. In standing, the pelvic aspect of the symphysis pubis faces nearly as much upwards as backwards and the sacral concavity is directed anteroinferiorly. The front of the symphysis and anterior superior iliac spines are in the same vertical plane. In sitting, body weight is transmitted through inferomedial parts of the ischial tuberosities, with variable soft tissues intervening. The anterior superior iliac spines are in a vertical plane through the acetabular centres, and the whole pelvis is tilted back with the lumbosacral angle somewhat diminished at the sacral promontory.