CHAPTER 46 Pectoral girdle, shoulder region and axilla

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

SKIN

Cutaneous vascular supply

The area over the lateral end of the clavicle is supplied by the supraclavicular artery which pierces the deep fascia superior to the clavicle and anterior to trapezius (Fig. 45.4). In the majority of cases this artery arises from the superficial cervical/transverse cervical artery, but it occasionally arises from the suprascapular artery. The area over the deltoid is supplied by the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries. The deltoid branch of the thoraco-acromial axis contributes to the blood supply of the anterior aspect of the shoulder via musculocutaneous perforators through deltoid. For details of the cutaneous supply to the anterior, lateral and posterior chest wall see page 915.

Cutaneous innervation

The segmental supply is described in Chapter 45, page 789. The cutaneous supply to the shoulder region comes from the supraclavicular nerves (p. 436, Fig. 45.15). The floor of the axilla together with part of the upper medial aspect of the arm is supplied by the intercostobrachial nerve (lateral branch of the second intercostal nerve). Occasionally the lateral branch of the third intercostal nerve contributes to the supply of skin in the floor of the axilla. The upper lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm supplies the skin over the inferolateral part of the shoulder.

SOFT TISSUE

Deep fascia

Pectoral and axillary fascia

The pectoral fascia is a thin lamina which covers pectoralis major and extends between its fasciculi. It is attached medially to the sternum, above to the clavicle and is continuous inferolaterally with the fascia of the shoulder, axilla and thorax. Although thin over pectoralis major, it is thicker between this muscle and latissimus dorsi, and forms the floor of the axilla as the axillary fascia. The latter divides at the lateral margin of latissimus dorsi into two layers, which ensheathe the muscle and are attached behind to the spines of the thoracic vertebrae. As the fascia leaves the lower edge of pectoralis major to cross the axilla, a layer ascends under cover of the muscle and splits to envelop pectoralis minor: it becomes the clavipectoral fascia at the upper edge of pectoralis minor. The hollow of the armpit is produced mainly by the action of this fascia in tethering the skin to the floor of the axilla, and it is sometimes referred to as the suspensory ligament of the axilla. The axillary fascia is pierced by the tail of the breast (Ch. 54).

BONE

CLAVICLE

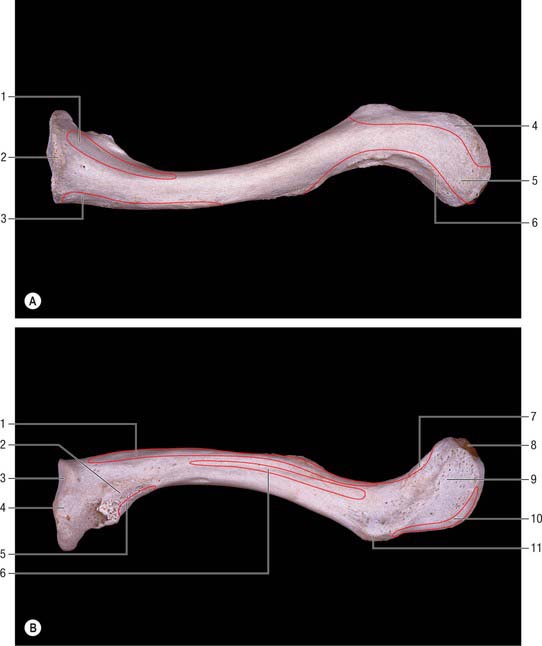

The clavicle lies almost horizontally at the root of the neck and is subcutaneous throughout its whole extent (Fig. 46.1). It acts as a prop which braces back the shoulder and enables the limb to swing clear of the trunk and transmits part of the weight of the limb to the axial skeleton. The lateral or acromial end of the bone is flattened and articulates with the medial side of the acromion, whereas the medial or sternal end is enlarged and articulates with the clavicular notch of the manubrium sterni and first costal cartilage. The shaft is gently curved and in shape resembles the italic letter f, being convex forwards in its medial two-thirds and concave forwards in its lateral third. The inferior aspect of the intermediate third is grooved in its long axis. The clavicle is trabecular internally, with a shell of much thicker compact bone in its shaft. Although elongated, the clavicle is unlike typical long bones in that it usually has no medullary cavity.

The female clavicle is shorter, thinner, less curved and smoother, and its acromial end is carried lower than the sternal in comparison with the male. In males the acromial end is on a level with, or slightly higher than, the sternal end when the arm is pendent. Midshaft circumference is the most reliable single indicator of sex: a combination of this measurement with weight and length yields better results. The clavicle is thicker and more curved in manual workers, and its ridges for muscular attachment are better marked.

Lateral third

The posterior border, also roughened by muscular attachments, is convex backwards. The superior surface is roughened near its margins but is smooth centrally, where it can be felt through the skin. The inferior surface presents two obvious markings. Close to the posterior border, at the junction of the lateral fourth with the rest of the bone, there is a prominent conoid tubercle which gives attachment to the conoid part of the coracoclavicular ligament. A narrow, roughened strip, the trapezoid line, runs forwards and laterally from the lateral side of this tubercle, almost as far as the acromial end (Fig. 46.1B). The trapezoid part of the coracoclavicular ligament is attached to it. A small oval articular facet, for articulation with the medial aspect of the acromion, faces laterally and slightly downwards at the lateral end of the shaft.

Subclavius lies in a groove on the inferior surface (Fig. 46.1B). The clavipectoral fascia is attached to the edges of the groove; the posterior edge of the groove runs to the conoid tubercle, where fascia and conoid ligament merge. Lateral to the groove there is a laterally inclined nutrient foramen. Deltoid (anterior) and trapezius (posterior) are attached to the lateral third of the shaft: both muscles reach the superior surface. The coracoclavicular ligament, which is attached to the conoid tubercle and trapezoid line (Fig. 46.1B), transmits the weight of the upper limb to the clavicle, counteracted by trapezius which supports its lateral part. From the conoid tubercle this weight is transmitted through the medial two-thirds of the shaft to the axial skeleton.

Medial two-thirds

The medial two-thirds provide attachment, anteriorly, for the clavicular head of pectoralis major: the area is usually clearly indicated on the bone. The clavicular head of sternocleidomastoid is attached to the medial half of the superior surface, but the marking on the bone is not very conspicuous. The smooth, posterior surface is devoid of muscular attachments except at its lower part immediately adjoining the sternal end, where the lateral fibres of sternohyoid are attached. Medially, this surface is related to the lower end of the internal jugular vein (from which it is separated by sternohyoid), the termination of the subclavian vein, and the start of the brachiocephalic vein. More laterally, it arches in front of the trunks of the brachial plexus and the third part of the subclavian artery. The suprascapular vessels are related to the upper part of this surface. The inferior surface gives insertion to subclavius in the subclavian groove: the clavipectoral fascia, which encloses subclavius, is attached to the edges of the groove. The posterior lip of the groove runs into the conoid tubercle and carries the fascia into continuity with the conoid ligament. A nutrient foramen is found in the lateral end of the groove, running in a lateral direction: the nutrient artery is derived from the suprascapular artery. The impression for the costoclavicular ligament is very variable in its character.

Ossification

The clavicle begins to ossify before any other bone in the body, and is ossified from three centres. The shaft of the bone is ossified in condensed mesenchyme from two primary centres, medial and lateral, which appear between the fifth and sixth weeks of intrauterine life, and fuse about the 45th day. Cartilage then develops at both ends of the clavicle. The medial cartilaginous mass contributes more to growth in length than does the lateral mass: the two centres of ossification meet between the middle and lateral thirds of the clavicle. A secondary centre for the sternal end appears in late teens, or even early twenties, usually 2 years earlier in females (Fig. 46.2). Fusion is probably rapid but reliable data are lacking. An acromial secondary centre sometimes develops at around 18 to 20 years, but this epiphysis is always small and rudimentary and rapidly joins the shaft.

SCAPULA

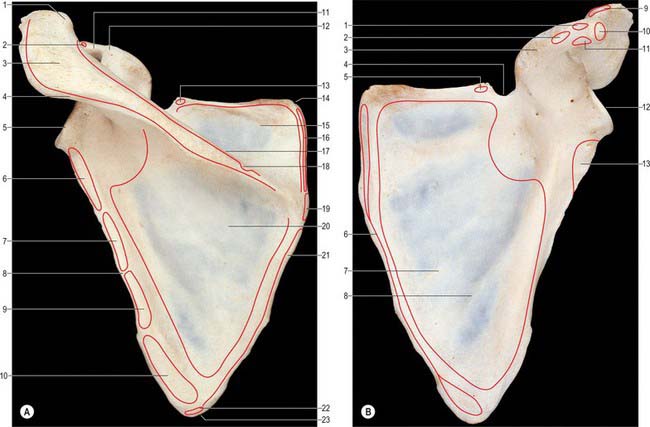

The scapula is a large, flat, triangular bone which lies on the posterolateral aspect of the chest wall, covering parts of the second to seventh ribs (Fig. 46.3, Fig. 46.4). It has costal and dorsal surfaces, superior, lateral and medial borders, inferior, superior and lateral angles, and three processes, the spine, its continuation the acromion and the coracoid process. The lateral angle is truncated and bears the glenoid cavity for articulation with the head of the humerus. This part of the bone may be regarded as the head, and it is connected to the plate-like body by an inconspicuous neck. The long axis of the scapula is nearly vertical and the relatively featureless costal surface can easily be distinguished from the dorsal surface, which is interrupted by the shelf-like projection of the spine (Fig. 46.3A). The bone is very much thickened in the immediate neighbourhood of the lateral border, which runs from the inferior angle below, to the glenoid cavity above. The main processes, and thicker parts of the scapula, contain trabecular bone; the rest consists of a thin layer of compact bone. The central supraspinous fossa and the greater part of the infraspinous fossa are thin and even translucent; occasionally the bone in them is deficient, and the gaps are filled by fibrous tissue.

Costal surface

The costal surface, which is directed medially and forwards when the arm is by the side, is slightly hollowed out, especially in its upper part (Fig. 46.3B).

Dorsal surface

The dorsal surface is divided by the shelf-like spine of the scapula into a small upper and a large lower area, which are confluent at the spinoglenoid notch between the lateral border of the spine and the dorsal aspect of the neck (Fig. 46.3A).

Superior border

The superior border, thin and sharp, is the shortest. At its anterolateral end it is separated from the root of the coracoid process by the suprascapular notch (Fig. 46.3B). Near the suprascapular notch it gives origin to the inferior belly of omohyoid. The notch is bridged by the superior transverse ligament which is attached laterally to the root of the coracoid process and medially to the limit of the notch. The ligament is sometimes ossified. The foramen, thus completed, transmits the suprascapular nerve to the supraspinous fossa, whereas the suprascapular vessels pass backwards above the ligament.

Lateral border

The lateral border of the scapula forms a clearly defined, sharp, roughened ridge, which runs sinuously from the inferior angle to the glenoid cavity. At its upper end it widens into a rough, somewhat triangular area, which is termed the infraglenoid tubercle (Fig. 46.4B). The lateral border separates the attachments of subscapularis and teres minor and major. These muscles project beyond the bone and, with latissimus dorsi, cover it so completely that it cannot be felt through the skin. The long head of triceps is attached to the infraglenoid tubercle.

The grooved part of the costal surface, the narrow flat lateral strip of the dorsal surface and the adjacent thickened ridge (Fig. 46.4B), are often included in the ‘lateral border’ during clinical examination.

Scapular angles

The inferior angle overlies the seventh rib or intercostal space. Palpable through the skin and covering muscles, it is also visible as it advances round the thoracic wall when the arm is raised. It is covered on its dorsal aspect by the upper border of latissimus dorsi, a small slip from which is frequently attached to the inferior angle. The superior angle, at the junction of the superior and medial borders, is obscured by the upper part of trapezius. The lateral angle, truncated and broad, bears the glenoid cavity which articulates with the head of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint. It provides a shallow, and limited, socket for the humeral head. Its outline is piriform, narrower above (Fig. 46.4B). The glenohumeral ligaments are attached to its anterior margin. When the arm is by the side, the cavity is directed forwards, laterally and slightly upwards. When the arm is raised above the head it is directed almost straight upwards. Just above it a small rough supraglenoid tubercle encroaches on the root of the coracoid process. The anatomical neck, the constriction adjoining the rim of the glenoid cavity, is most distinct at its inferior and dorsal aspects. Anteriorly and posteriorly it extends between the infraglenoid and supraglenoid tubercles, passing lateral to the root of the coracoid process. The long head of biceps brachii is attached to the supraglenoid tubercle, and the long head of triceps brachii is attached to the infraglenoid tubercle.

Spine of the scapula

The spine of the scapula forms a shelf-like projection on the upper part of the dorsal surface of the bone, and is triangular in shape (Fig. 46.3A). Its lateral border is free, thick and rounded and helps to bound the spinoglenoid notch, which lies between it and the dorsal surface of the neck of the bone. Its anterior border joins the dorsal surface of the scapula along a line which runs laterally and slightly upwards from the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the medial border. The plate-like body of the bone is bent along this line, which accounts for the concavity of the upper part of the costal surface. The dorsal border is the crest of the spine, and is subcutaneous throughout nearly its whole extent. At its medial end the crest expands into a smooth, triangular area. Elsewhere the upper and lower edges and the surface of the crest are roughened for muscular attachments. The upper surface of the spine widens as it is traced laterally, and is slightly hollowed out. Together with the upper area of the dorsal surface of the bone, the upper surface of the spine forms the supraspinous fossa. The lower surface is overhung by the crest at its medial, narrow end, but is gently convex in its wider, lateral portion. Together with the lower area of the dorsal surface of the bone, the lower surface of the spine forms the infraspinous fossa, which communicates with the supraspinous fossa through the spinoglenoid notch.

Coracoid process

The coracoid process arises from the upper border of the head of the scapula and is bent sharply so as to project forwards and slightly laterally (Fig. 46.3B, Fig. 46.4A). When the arm is by the side, the coracoid process points almost straight forwards and its slightly enlarged tip can be felt through the skin, although it is covered by the anterior fibres of deltoid. The supraglenoid tubercle marks the root of the coracoid process where it adjoins the upper part of the glenoid cavity. There is another impression on the dorsal aspect of the coracoid process at the point where it changes direction: it gives attachment to the conoid part of the coracoclavicular ligament.

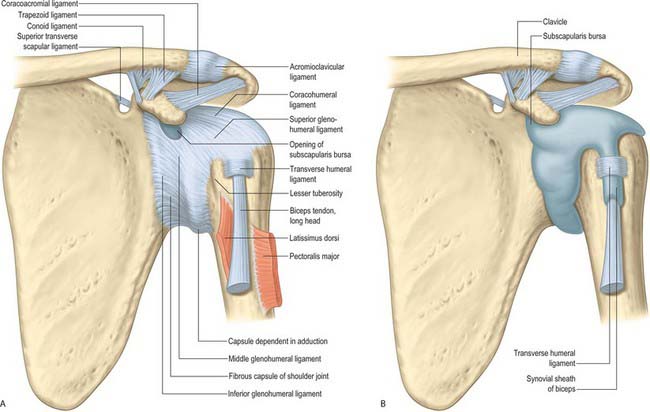

Ligaments

The main scapular ligaments are the coracoacromial and superior transverse scapular; there may also be a weaker, variable inferior transverse scapular (spinoglenoid) ligament (see below Fig. 46.13, see below Fig. 46.14).

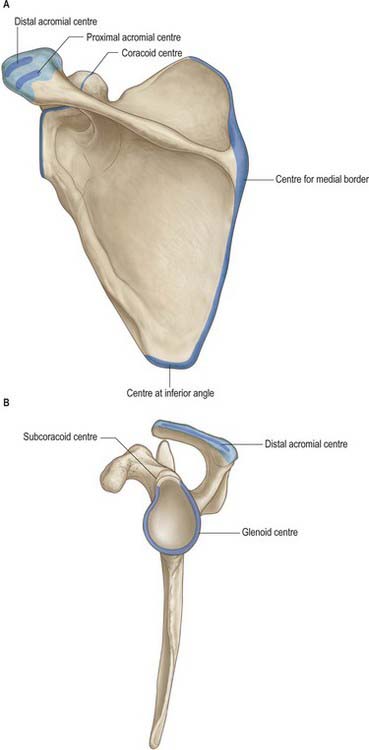

Ossification

The cartilaginous scapula is ossified from eight or more centres: one in the body, two each in the coracoid process and the acromion, one each in the medial border, inferior angle and lower part of the rim of the glenoid cavity (Fig. 46.5). The centre for the body appears in the eighth intrauterine week. Ossification begins in the middle of the coracoid process in the first year or in a small proportion of individuals before birth and the process joins the rest of the bone about the 15th year. At or soon after puberty centres of ossification occur in the rest of the coracoid process (subcoracoid centre), in the rim of the lower part of the glenoid cavity, frequently at the tip of the coracoid process, in the acromion, in the inferior angle and contiguous part of the medial border and in the medial border. A variable area of the upper part of the glenoid cavity, usually the upper third, is ossified from the subcoracoid centre; it unites with the rest of the bone in the 14th year in the female and the 17th year in the male. A horse-shoe shaped epiphysis appears for the rim of the lower part of the glenoid cavity; thicker at its peripheral than at its central margin, it converts the flat glenoid cavity of the child into the gently concave fossa of the adult. The base of the acromion is formed by an extension from the spine; the rest of the acromion is ossified from two centres which unite and then join the extension from the spine. The various epiphyses of the scapula have all joined the bone by about the 20th year.

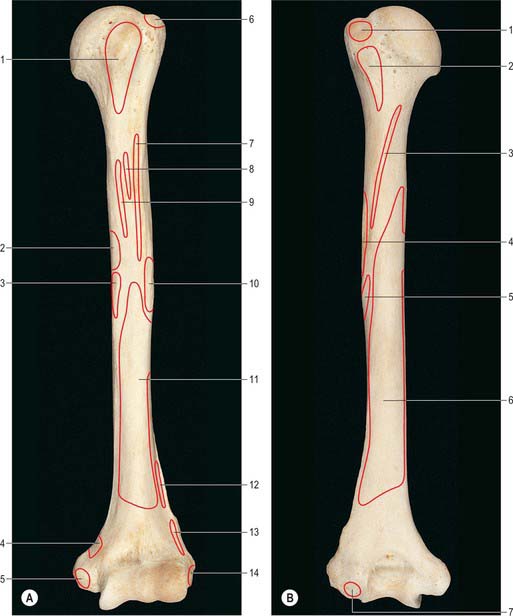

HUMERUS

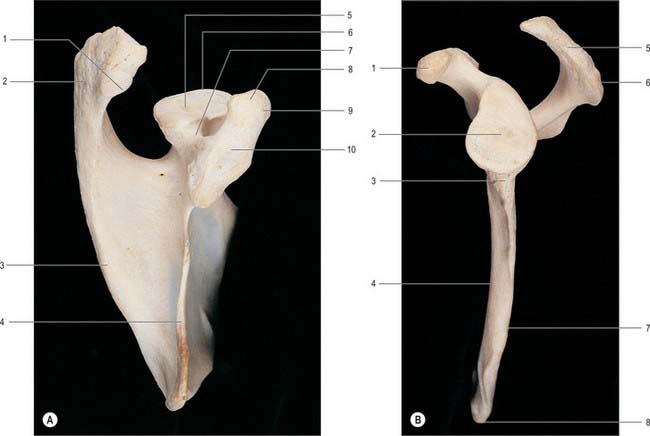

The humerus, the longest and largest bone in the upper limb, has expanded ends and a shaft (Fig. 46.6, Fig. 46.7, Fig. 46.8). The rounded head occupies the proximal and medial part of the upper end of the bone and forms an enarthrodial articulation with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. The lesser tubercle projects from the front of the shaft, close to the head, and is limited on its lateral side by a well-marked groove. The distal end, loosely termed ‘condylar’, is adapted to the forearm bones at the elbow joint.

Proximal end

The proximal end of the humerus consists of the head, anatomical neck and the greater and lesser tubercles. It joins the shaft at an ill-defined ‘surgical neck’, which is closely related on its medial side to the axillary nerve and posterior humeral circumflex artery (Fig. 46.7).

Head

The head of the humerus forms rather less than half a spheroid; in sectional profile it is spheroidal (strictly ovoidal) (Fig. 46.7). Its smooth articular surface is covered with hyaline cartilage, which is thicker centrally. When the arm is at rest by the side, it is directed medially, backwards and upwards to articulate with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. The humeral articular surface is much more extensive than the glenoid cavity, and only a portion of it is in contact with the cavity in any one position of the arm.

Anatomical neck

The anatomical neck of the humerus immediately adjoins the margin of the head and forms a slight constriction, which is least apparent in the neighbourhood of the greater tubercle, and superiorly, and for some distance anteriorly and posteriorly: it indicates the line of capsular attachment of the shoulder joint (Fig. 46.7), other than at the intertubercular sulcus, where the long tendon of biceps emerges. Medially, the capsular attachment diverges from the anatomical neck and descends 1 cm or more onto the shaft.

Lesser tubercle

The lesser tubercle is anterior to and just beyond the anatomical neck. It has a smooth, muscular impression on its upper part palpable through the thickness of deltoid 3 cm below the acromial apex. The bony prominence slips away from the examining finger when the humerus is rotated. The lateral edge of the lesser tubercle is sharp and forms the medial border of the intertubercular sulcus. Subscapularis is attached to the lesser tubercle (Fig. 46.6A), and the transverse ligament of the shoulder joint is attached to the lateral margin.

Greater tubercle

The greater tubercle is the most lateral part of the proximal end of the humerus. It projects beyond the lateral border of the acromion. Its posterosuperior aspect, near the anatomical neck, bears three smooth flattened impressions for the attachment of supraspinatus (uppermost), infraspinatus (middle) and teres minor (lowest and placed on the posterior surface of the tubercle) (Fig. 46.6). The attachments of subscapularis and teres minor are not confined to their respective tubercles, but extend for varying distances on to the adjacent metaphysis. The projecting lateral surface of the tubercle presents numerous vascular foramina and is covered by the thick, fleshy deltoid, which produces the normal rounded contour of the shoulder. A part of the subacromial bursa may cover the upper part of this area and separate it from deltoid.

Shaft

Surfaces

The anterolateral surface is bounded by the anterior and lateral borders and is smooth and featureless in its upper part, which is covered by deltoid. About, or a little above, the middle of this surface, deltoid is inserted into the deltoid tubercle; further distally the surface gives origin to the lateral fibres of brachialis, which extend upwards into the floor of the lower end of the groove for the radial nerve (Fig. 46.6). Brachioradialis is attached to the proximal two-thirds of the roughened anterior aspect of the lateral supracondylar ridge, and extensor carpi radialis longus is attached to its distal third. Behind these muscles, the ridge gives attachment to the lateral intermuscular septum of the arm.

The anteromedial surface is bounded by the anterior and medial borders. Rather less than its upper third forms the rough floor of the intertubercular sulcus; the rest of the surface is smooth. Distal to the intertubercular sulcus a small area of the anteromedial surface is devoid of muscular attachment, but its lower half is occupied by the medial part of brachialis (Fig. 46.6A). Coracobrachialis is attached to a roughened strip on the middle of the medial border. The humeral head of pronator teres is attached to a narrow area close to the lowest part of the medial supracondylar ridge, and the ridge itself gives attachment to the medial intermuscular septum of the arm.

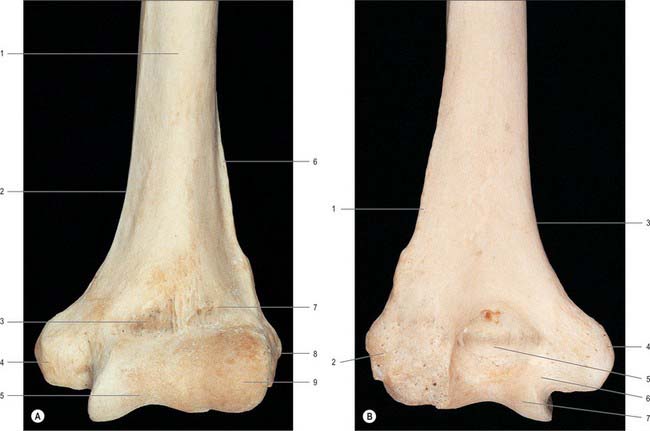

Distal end

The distal end of the humerus is a modified condyle: it is wider transversely and has articular and non-articular parts (Fig. 46.8, Fig. 46.9). The articular part is curved forwards, so that its anterior and posterior surfaces lie in front of the corresponding surfaces of the shaft. It articulates with the radius and the ulna at the elbow joint, and is divided by a faint groove into a lateral capitulum, and a medial trochlea.

Lateral epicondyle

The lateral border of the humerus terminates at the lateral epicondyle, and its lower portion constitutes the lateral supracondylar ridge. The lateral epicondyle occupies the lateral part of the non-articular portion of the condyle, but does not project beyond the lateral supracondylar ridge. It turns slightly forwards, unlike the medial epicondyle, which turns slightly backwards. Its lateral and anterior surfaces show a well-marked impression for the superficial group of the extensor muscles of the forearm (Fig. 46.6B), which arise from the lateral side of the lower humeral epiphysis, and, like the flexors, are situated outside the articular capsule. The posterior surface, which is very slightly convex, is easily felt in a depression visible behind the extended elbow. A small area on the posterior surface gives origin to anconeus.

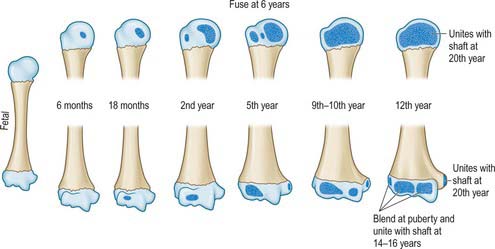

Ossification

The humerus is ossified from eight centres, in the shaft, head, greater and lesser tubercles, capitulum with the lateral part of the trochlea, the medial part of the trochlea, and one for each epicondyle (Fig. 46.10). The centre for the shaft appears near its middle in the eighth week of intrauterine life, and gradually extends towards the ends. Before birth (20%), or in the first six months afterwards, ossification begins in the head, during the first year in females and second year in males in the greater tubercle, and about the fifth in the lesser tubercle. The existence of a centre in the lesser tubercle is often questioned, perhaps because it is often obscured in the usual anteroposterior radiological views (Fig. 46.11).

JOINTS

STERNOCLAVICULAR JOINT

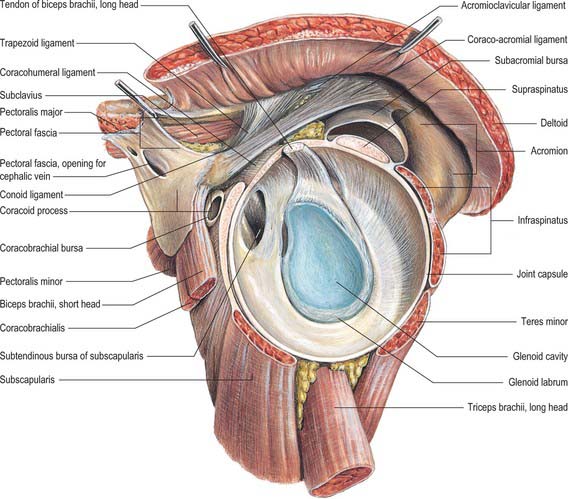

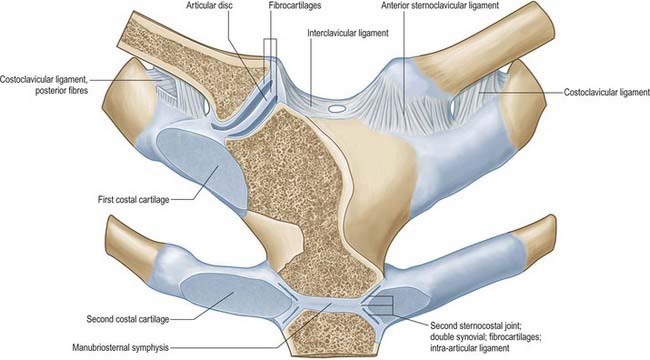

The articulating surfaces are the sternal end of the clavicle and the clavicular notch of the sternum, together with the adjacent superior surface of the first costal cartilage (Fig. 46.12). The larger clavicular articular surface is covered by fibrocartilage, which is thicker than the fibrocartilaginous lamina on the sternum. The joint is convex vertically but slightly concave anteroposteriorly, and is therefore sellar; the clavicular notch of the sternum is reciprocally curved, but the two surfaces are not fully congruent. An articular disc completely divides the joint.

The costoclavicular ligament is like an inverted cone, but short and flattened. It has anterior and posterior laminae which are attached to the upper surface of the first rib and costal cartilage, and ascends to the margins of an impression on the inferior clavicular surface at its medial end. Fibres of the anterior lamina ascend laterally and those of the posterior lamina (which are shorter) ascend medially (Fig. 46.12); they fuse laterally and merge medially with the capsule.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree