Medicines that are prescribed but not taken by patients represent a large loss in drug and prescribing costs and an enormous waste of expensive health professionals’ time. In 2007 the National Audit Office estimated that about £100 million is wasted each year on medication dispensed but returned to pharmacies. The aim of this chapter is to introduce the reader to the concepts of adherence, compliance and concordance with respect to medicine management. Nurses need to have an understanding of pharmacology at a level which will allow them to inform and educate the patients in their care. Without effective information and education surrounding their medications, many patients are unable to understand the need for them to take their medications as prescribed to ensure optimum drug performance.

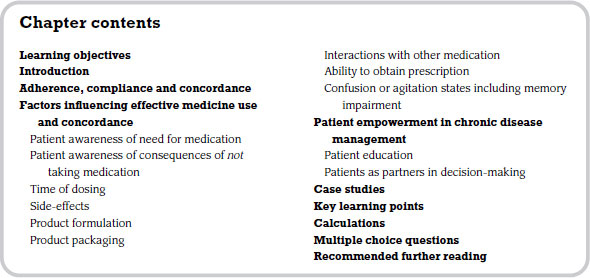

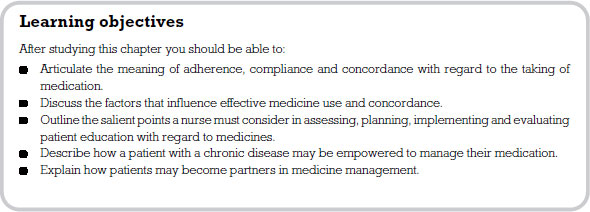

Adherence, compliance and concordance

Much of the time, we use the terms adherence, compliance and concordance almost interchangeably, when in fact they each have quite different and specific meanings.

Adherence has a dictionary definition that suggests sticking to something. When we talk about patients adhering to their medication regimen we quite literally mean: are they sticking to the prescribed instructions for taking their medication? For a patient to adhere to their medication regimen, they need very little information from the prescriber. They attend a consultation and present the prescriber with a problem or symptom. The prescriber makes a diagnosis, prescribes the medication and the patient is issued with a prescription to take for dispensing. Information needs to be given verbally to the patient about how to take their medication, and printed instructions are issued with their drugs. The patient needs to read the instructions or follow the prescriber’s guidance and adhere to that. The knowledge gained from the information given should make the reasons for adherence clear to the patient. The prescriber should also consider aspects of the medication regimen that may make adherence difficult for the patient and factor them into any decision-making. This adherence may seem an obvious thing for patients to do, but patients frequently, and for many reasons, take their medication in a manner other than the instructions with which they were issued with by the prescriber. Non-adherence to medication regimens can have serious consequences, depending on the medication being prescribed. Failure to adhere is, not surprisingly, a particular problem in the management of chronic illness, especially when the patient does not feel ill. Some of the drug therapies covered in Chapter 7 of this book like asthma, diabetes and hypertension incur especially high levels of non-adherence and it is common for patients to alter or abandon taking their drugs.

Compliance with a medication regimen differs from the act of simply adhering to it. By complying with the prescriber’s instructions the patient automatically adheres to the medication regimen. But compliance suggests that information is given to allow the patient to make the choice to comply. There is some involvement of the patient in the medication regimen, but compliance relies largely on the patient following the prescriber’s recommendations. Some patients do not like the term ‘compliant’ as it suggests that if they diverge from the regimen, they are seen as non-compliant, a negative term.

Concordance is where the patient–prescriber relationship surrounding medication regimens is seen to be more equal in footing and there is a current initiative to further involve patients in the treatment process and so improve their compliance and adherence. This requires an active participation by the patient, and a confident and self-aware prescriber or medicines educator. Concordance involves the sharing of knowledge, understanding and beliefs by both parties. The prescriber offers their knowledge and expertise of the condition to be treated and the range (if appropriate) of treatment options available, be they pharmacological or non-pharmacological. The prescriber then provides information about the medicines to be considered including any cautions, contraindications and side-effects. This gives the patient an informed choice. Patients bring their knowledge of their lifestyle and practices to the equation. This can include work patterns, social, religious and cultural aspects, and practicalities, such as an ability to open medicine bottles. This can help the prescriber to narrow the range of prescription options available. By good knowledge-sharing and communication an effective decision as to the most appropriate medicine to be prescribed can more easily be reached and the result is likely to improve concordance and compliance. It could be argued that all of this should happen in the adherence model and for many patients it does. The goal is ultimately for the patient to take their prescribed medicine in the most effective way in order for their condition to improve. In 2009, NICE published guidance on medicines adherence which is concerned with enabling patients to make informed choices by involving and supporting them in decisions about prescribed medicines. At this time it is the most up-to date resource for prescribing in the UK.

Factors influencing effective medicine use and concordance

There are many factors which can influence a patient’s ability to adhere, comply or demonstrate concordance when it comes to medications. Non-compliance and non-adherence may be an intentional act on behalf of the patient or may be an involuntary act of which they are not even aware. Both can often be associated with the amount and quality of education and information given by the prescriber, dispenser and administrator of the medication at the time treatment is initiated. It may be that the impact of the medication regimen on the patient’s daily routine is intolerable to them. They may not be able to take the medication as prescribed or even attend to the filling of their prescription. It may equally be that they feel that by taking the medication in a way other than prescribed by the doctor, they are exerting control over the situation to improve, in their minds, the likely outcome.

The main factors to consider can be summarized as follows:

- patient awareness of need for medication;

- patient awareness of consequences of not taking medication;

- time of dosing;

- side-effects;

- product formulation;

- product packaging;

- interactions with other medication;

- ability to obtain prescription;

- confusion or agitation states including memory impairment.

Patient awareness of need for medication

It is important that patients are fully aware of the need for them to take their medication. This may seem an obvious statement, but in some cases patients do not want to take medication, and if they are not fully cognizant of the need for the medication, non-adherence can occur. This can be especially true in patients who have received a diagnosis when they had not been feeling unwell. An example is when a condition is picked up on routine screening (e.g. raised blood pressure). The importance of taking antihypertensive medication should be explained thoroughly and the prescriber should also outline the consequences of not taking the medicine.

Patient awareness of consequences of not taking medication

This is perhaps more important than the reasons for taking medication. Patients’ perceptions of the benefits and risks of taking medication have been shown to influence compliance. Using the example of high blood pressure, there are many consequences of not taking antihypertensive medication. The continual presence of a raised blood pressure increases the patient’s risk of stroke and heart attack, both of which can lead to premature death. It cannot therefore be understated how important good information and education are in this area.

This can be very important for some patients. A good example is antibiotic prescriptions. Some schools will not administer medications to children during school hours but insist on a parent coming in to give the medicines. For a child who is prescribed antibiotics three or four times per day and is well enough to attend school, necessitating dosing during school hours, this can be problematic. It could lead to the child being kept off school, the parent missing work or the antibiotics being taken inappropriately. It may be prudent therefore to consider prescribing an antibiotic that can be taken once or twice daily that can be appropriately administered around school hours.

Side-effects

Intolerable side-effects are one of the main reasons for non-compliance with medicine regimens. No drug is completely free from side-effects, but some effects are tolerable for some patients but may not be for others. Information and education about potential side-effects is vital in medicines management. If a patient experiences side-effects it may lead to them stopping the medication and possibly not seeking advice from the prescriber. A good example here is Citalopram, an antidepressant medication which can cause nausea as a side-effect. This nausea is usually transient and will pass after about two weeks, hence it is important to educate the patient about this, as most people can put up with a mild side-effect for a short period if they know it will pass, and they will continue with the medication.

Some side-effects can be severe and may even become adverse for the patient if left unchecked. It is very important to stress to patients that if they experience any side-effects they should seek advice at once.

Product formulation

In some cases, the simple formulation of the medication makes adhering to the regimen difficult if not impossible. Children are an important group to consider from this point of view. Many children under the age of 10 have great difficulty in swallowing tablets, so liquid medicine is the preferred choice. Some children, especially smaller children, will also dislike the taste of their medicine. If this is analgesia, it is worth the parent trying different brands, as they can be obtained in different flavours to help them find a product suitable for their child.

In inflammatory bowel disease the use of rectal medication can be a cause for concern. For some patients rectal medication is unacceptable and produces anxiety regarding the route of administration. Even with a clear educational plan of action, to expect a patient to use medication that produces such anxiety may be unrealistic. This issue should be thoroughly explored with the patient before treatment is prescribed.

Product packaging

The elderly or those with manual dexterity problems can often have trouble with product packaging. The main problem is child-proof caps on medicine bottles, but some blister packs can prove difficult to get into as well. Dispensing pharmacies are able to help with this if asked. Tablets can be supplied in bottles with normal caps on request. Medication can also be supplied in easy-to-open packs.

Interactions with other medication

Although patients may be taking their medication as prescribed, it is important to consider other medication or specific instructions on timing of dosing. Some drugs are not fully absorbed from the stomach if they are taken at the same time as an antacid preparation. Some should be taken with food, others after food and still others before food, so it is important that the patient takes their medicines exactly as prescribed to ensure optimum effect.

Ability to obtain prescription

For some elderly or infirm patients this could be a hurdle to medication adherence. If the patient cannot physically go to the pharmacy to collect their prescription, it follows that they cannot take the medication. This has become much less of a problem as a result of initiatives by some pharmacies to collect prescriptions, issue the medication and deliver it to the patient’s home. Many community pharmacies offer this service and will collect repeat prescriptions direct from the doctor’s surgery. It is important that patients are made aware of this service where it exists.

Obtaining a prescription for some people may start with the priority of which medications they can afford. Not all people who require a large number of medicines get help in paying for them. Some people in employment who have to pay for their prescriptions ration themselves to those medications that they perceive to be the most important or most obviously efficacious. The ‘lesser’ medications (in the patient’s eyes) may not be purchased.

Confusion or agitation states including memory impairment

If patients who suffer from agitation states and/or memory impairment are on several different medications, their condition in itself can cause problems in terms of adherence and compliance. Multi-dose boxes and dated boxes are available and can be made up by pharmacies for all the medicines needed. Such boxes have a strip for each day, with time to take the medication highlighted. This allows patients to see whether or not they have taken their medication. In more severe cases, patients may need family or carers to administer their medicines.

Forgetfulness is a major cause of non-compliance. Patients should be taught behaviour strategies such as reminders, self-monitoring tools, cues and reinforcements. The use of aids, such as the dosette box, should not be viewed as just having a use for older people, but for those with unstructured or hectic lifestyles such as the young.

Patient empowerment in chronic disease management

Patients who suffer from long-term or chronic diseases often want to be empowered in the management of their conditions, and this can include the choice and modification of any medications prescribed. They can feel despondent about having to take medication for life, and naturally want the medication to treat their condition with minimal impact on their lifestyle and routine. More and more patients want to be involved and to feel in control of their disease, rather than it controlling them. Education and information is the key in patient empowerment. Education allows patients to develop a knowledge and understanding of their disease and its management, and is sometimes equivalent to that of the health professional involved in their care. There is a wealth of sources of information for patients. The internet and its many search facilities have dramatically opened up the amount of information available, however there can be problems with accessing the internet. In areas of low socioeconomic status, access to global information may become entangled with economics and therefore inequalities in medicine information almost certainly exist.

For patients not able to access the internet, information can be provided by leaflet format, or by attendance at ‘help’ groups, often formed for many chronic diseases. This is no substitute for good information provided by health care professionals, but can serve to augment that information.

Patient education

This should be individualized to the patient and is an important component of nursing care. Patients should have an individualized medication programme as part of their discharge plan. The nurse should provide the patient with medication leaflets to promote recall of details given to them during any medication teaching. Before teaching patients, nurses should plan what the session aims to achieve and what the outcomes of the session should be. When developing a teaching plan, nurses should allocate time to discuss with patients what they would like to know about their medication. Do not forget that some patients are very knowledgeable about their condition and the medicines that they take. Therefore it is important not to be patronizing and to seek out the patient’s level of knowledge prior to undertaking an educational role. The importance of the nurse understanding aspects of pharmacology is paramount. This is why you need to carry on increasing your knowledge in this area.

Once patients leave hospital other members of the primary care team have a duty to continue a more long-term education plan with regard to their medicines. Primary care specialists, GPs and pharmacists should be involved in information-giving and evaluation of the patient’s level of concordance. This is especially important with elderly people as the medication regimens in this group tend to be complex.

Patients as partners in decision-making

Except when patients are in hospital, it is they who have to manage their own medication. Ironically it is often patients themselves who remain passive when it comes to consulting with health care professionals about their medicine management and behavioural changes. It is a relatively new concept for us to consider the patient as a partner in any decision-making process with regard to the management of their care, let alone bringing medication into the arena. This is, however, the main factor to consider in promoting concordance. The good consultation skills of a health care professional should always include the patient at all stages of the consultation. Patient trust and cooperation can enhance the information obtained by the health care professional which subsequently improves the outcome of the session.

Many patients want to be active partners in decision-making and this should be encouraged. People are often more likely to take their medication if they can hear themselves putting forward solutions. Therefore, asking patients’ views, listening and helping them think the problem through and make a decision is more effective than telling them what to do.

Listening skills are important in information exchange so that both parties can think about and reflect on each other’s viewpoint. The nurse needs to be aware of verbal and non-verbal cues which may indicate that the patient is becoming reluctant or defensive. Such a reaction usually means that the approach taken by the nurse is making the patient feel uncomfortable. The nurse therefore must develop an increased level of sensitivity and understanding of the interaction taking place.

It is however essential that the partnership is functional. Some patients feel that because this is their disease they will make the decisions. This can lead to an inappropriate balance in the partnership and may be detrimental, with the knowledge and expertise of the health care professional not being acknowledged.

Some patients do not want to be active partners in decision-making, and their wishes should not be ignored. Many patients come to see their doctor with a symptom or problem, want the doctor to make a diagnosis and prescribe treatment. They respect the doctor’s knowledge and expertise and many feel that ‘doctor knows best’. This attitude actually requires more skill on behalf of the prescriber who, in order to most appropriately prescribe, requires information about lifestyle and practices that will enable them to make a more informed decision.

Relapse is common, so the need for open discussion is extremely important. All nurses need to acknowledge that it is possible that a patient may want to stop or change their medication.

A number of psychological models have been developed in order to understand health behaviours relevant to compliance. The most popular model is the health belief model which puts forward the view that health-related behaviours or the seeking of health interventions depend on four factors:

1. perceived susceptibility (the person’s assessment of their risk of getting an illness);

2. perceived severity (the person’s assessment of the seriousness of the illness, and what this could mean for them);

3. perceived barriers (the person’s assessment of any influences which may discourage the adoption of health-related behaviours);

4. perceived benefits (the person’s assessment of the beneficial outcomes of adopting a health-related behaviour).