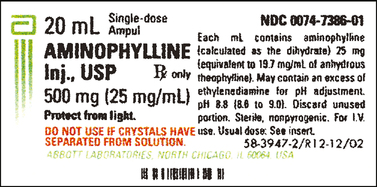

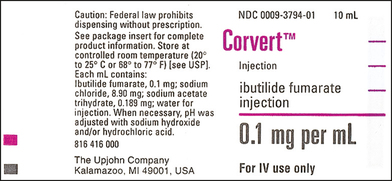

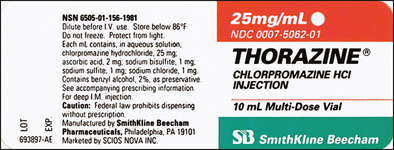

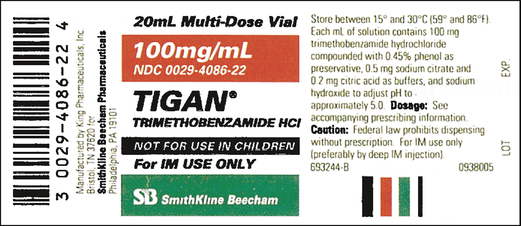

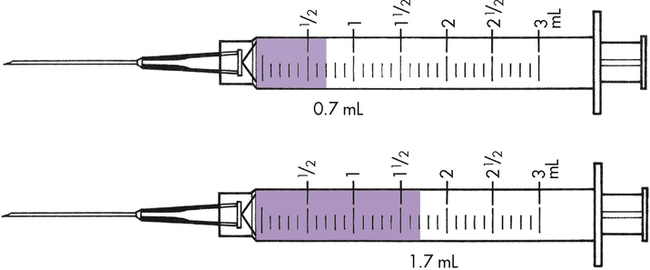

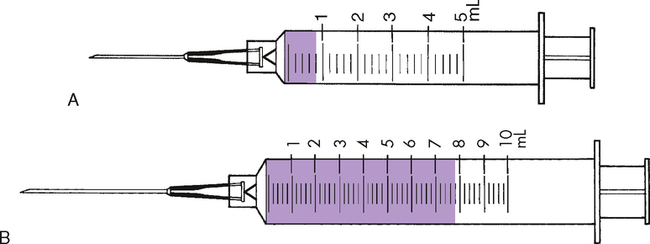

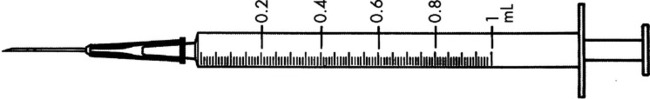

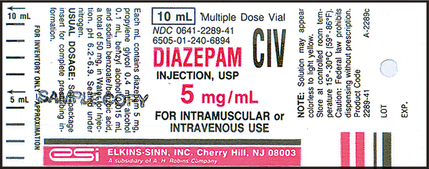

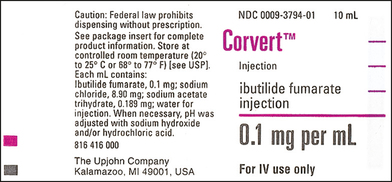

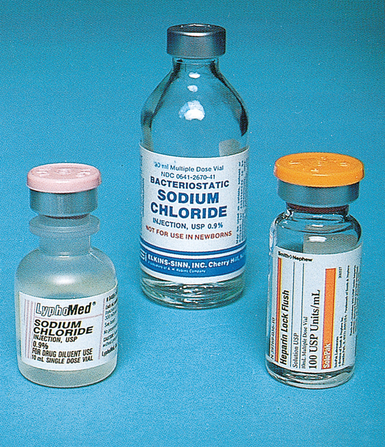

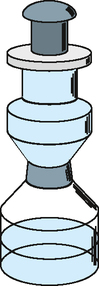

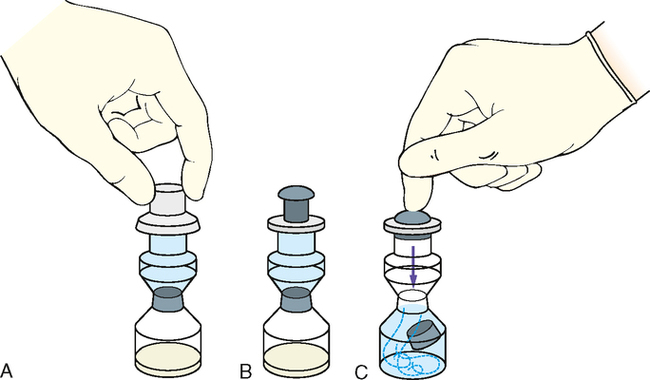

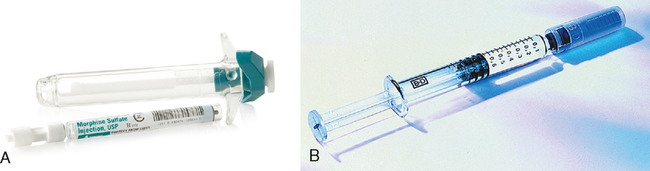

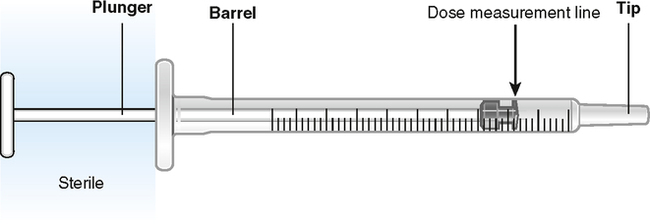

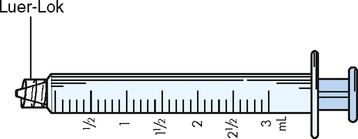

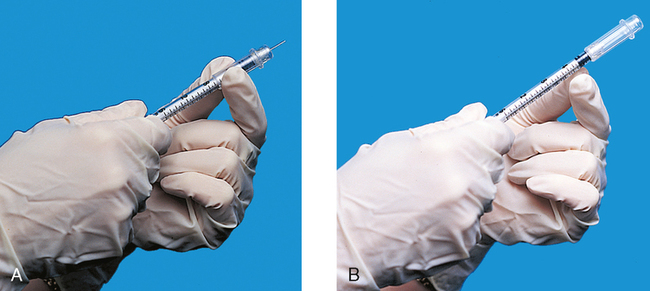

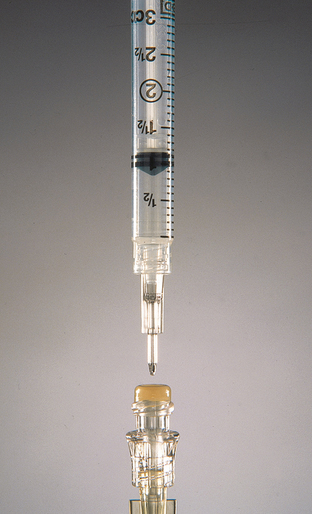

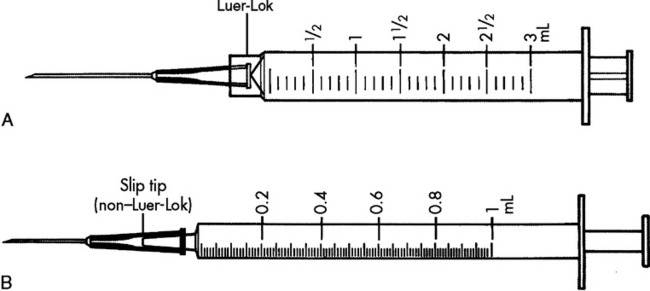

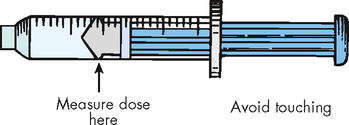

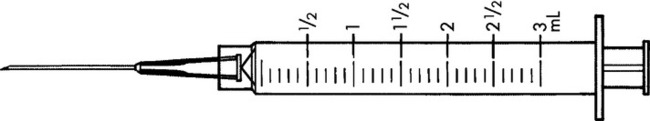

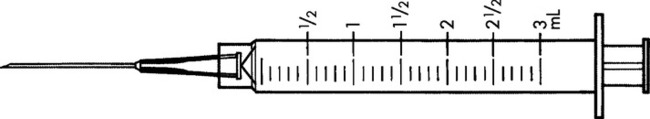

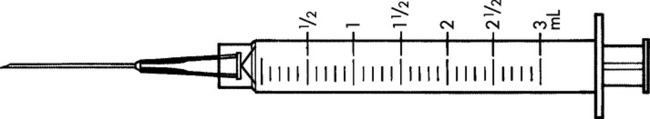

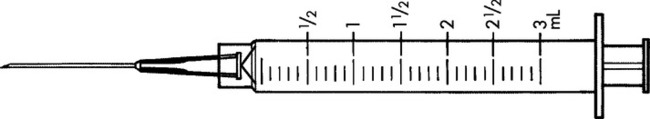

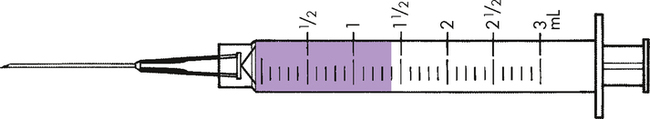

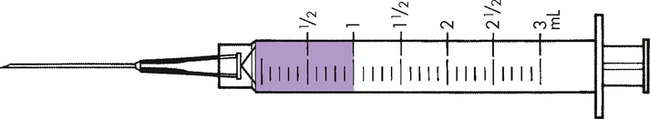

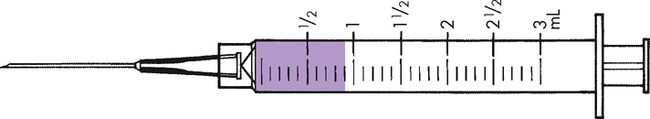

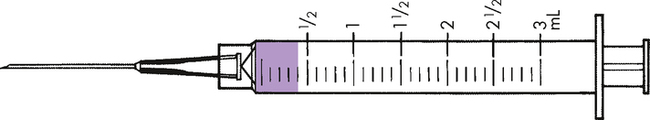

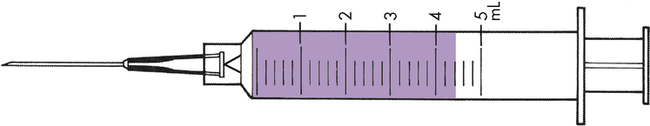

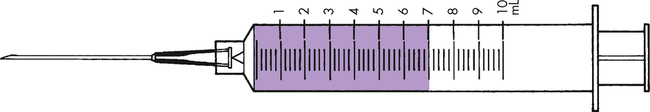

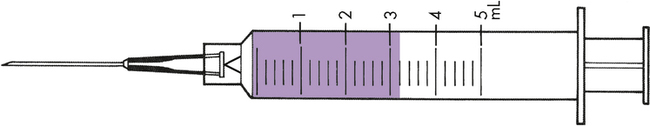

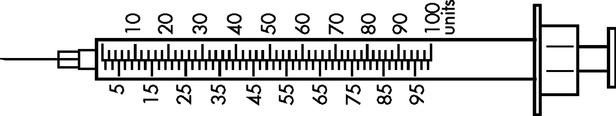

CHAPTER 18 After reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Identify the various types of syringes used for parenteral administration 2. Read and measure dosages on a syringe 3. Read medication labels on parenteral medications 4. Calculate dosages of parenteral medications already in solution 5. Identify appropriate syringes with which to administer dosages calculated Medications for parenteral use are available as a sterile solution or liquid that can be absorbed and distributed without causing irritation to the tissues. Parenteral medications are also available in powder form that must be diluted with a liquid or solvent (reconstituted) before they can be used. Reconstitution of medications in powder form will be covered in Chapter 19. Medications for parenteral use come packaged in vials, ampules, and premeasured (prefilled) syringes and cartridges. Parenteral medications are packaged in various forms: 1. Ampule—An ampule is a sealed glass container designed to hold a single dose of medication. Ampules have a particular shape with a constricted neck. They are designed to snap open. The neck of the ampule may be scored or have a darkened line or ring around it to indicate where it should be broken to withdraw medication (Figure 18-1). 2. Vial—A vial is a plastic or glass container that has a rubber stopper (diaphragm) on the top. The rubber stopper is covered with a metal lid or plastic cover to maintain sterility until the vial is used for the first time (Figure 18-2). Some manufacturers do not guarantee a sterile top even though it is covered, and therefore it is necessary to wipe the top with alcohol even with first use. Vials are available in different sizes. Multidose vials contain more than one dosage of the medication. The label on the vial will specify the amount of medication in a certain amount of solution, for example, 60 mg per mL or 0.2 mg per 0.5 mL. Single-dose vials contain a single dosage of medication for injection. Many vials are single dose, because it is safer. Even if medication is in a single-dosage vial, it should still be measured and not just drawn up. The medication in a vial may be in liquid (solution) form, or it may contain a powder that must be reconstituted before administration. 3. Mix-o-vial—Some medications come in mix-o-vials (Figure 18-3), for example, Solu-Medrol and Solu-Cortef. The vial usually contains a single dosage of medication. The mix-o-vial has two compartments separated by a rubber stopper. The top compartment contains the sterile liquid (diluent), and the bottom compartment contains the powdered medication. When pressure is applied to the top of the vial, the rubber stopper that separates the medication and liquid is released. This allows the liquid and medication to be mixed, thereby dissolving the medication (Figure 18-4). A needle is inserted into the rubber stopper to withdraw the medication. 4. Cartridge—Some medications are packaged in a prefilled glass or plastic container. The cartridge is clearly marked, indicating the amount of medication in it. Certain cartridges require a special holder called a Tubex or Carpuject to release the medication from the cartridge. The cartridge contains a single dosage of medication. If the dosage to be administered is less than the amount contained in the unit, discard the unneeded portion if any, and then administer the medication (Figure 18-5). 5. Prepackaged syringe (premeasured)—The medication comes prepared for administration in a syringe with the needle attached or without a needle attached. A specific amount of medication is contained in the syringe. The amount desired is calculated, the excess disposed of, and the calculated dosage is administered. These syringes are for single use only. Valium and Lovenox are examples of medications that come in prepackaged syringes (see Figure 18-5, B). Various-sized syringes are available for use. They have different capacities and specific calibrations. Syringes are made of plastic and glass, but plastic syringes are more commonly used. They are disposable and designed for one-time use only. Syringes have three parts (Figure 18-6): 1. The barrel—The outer calibrated portion that holds the medication. 2. The plunger—The inner device that is moved backward to withdraw and measure the medication and is pushed to eject the medication from the syringe. 3. The tip—The end of the syringe that holds the needle. The tip can be plain (slip tip) or Luer-Lok (Figure 18-7). It is important to note that needle-stick prevention has become increasingly important in preventing transmission of blood-borne infections from contaminated needles. Consequently, this has resulted in special prevention techniques (e.g., no recapping of a needle after use) and development of special equipment, such as syringes with a sheath or guard that covers the needle after it is withdrawn from the skin, thereby decreasing the chance of needle-stick injury (Figure 18-8). Another advance in safety needle technology is the safety glide syringe, which contains a protective needle guard that can be activated by a single finger to cover and seal the needle after injection (Figure 18-9). Needleless syringe systems have also been designed to prevent needle sticks during intravenous administration (Figure 18-10). The three types of syringes are hypodermic, tuberculin, and insulin. Hypodermic syringes come in a variety of sizes from 0.5 to 60 mL and larger. Syringes are calibrated or marked in milliliters but hold varying capacities. Of the small-capacity syringes, the 3-mL syringe is used most often for the administration of medication that is more than 1 mL; however, hypodermic syringes are also available in larger sizes (10 mL 20 mL, 50 mL, and larger). Although many syringes are labeled in milliliters, a few syringes are still labeled with cubic centimeters (cc). It is important to note that milliliter (mL) is correct. The milliliter is a measure of volume, the cubic centimeter is a three- dimensional measure of space and represents the space that a milliliter occupies. The terms, although sometimes used interchangeably, are not the same. Many institutions are now purchasing syringes that indicate mL as opposed to cc. This text shows mL on syringes, not cc. Some of the small-capacity syringes (1, 2, 3 mL) may still indicate minims. The use of the minim scale is rare and discouraged because of its inaccuracy. Although a few syringes still have minim markings, more institutions are purchasing syringes that do not have minim markings on them to discourage their use (Figure 18-11). It has been found that most errors in dosage measurement occur from misreading the minim scale. For small hypodermics, decimal numbers are used to express dosages (e.g., 1.2 mL, 0.3 mL). Notice that small hypodermics up to 3-mL size also have fractions on them (see Figure 18-11). There are, however, some syringes that indicate 0.5 mL, 1.5 mL, etc., instead of fractions. The use of decimals on the syringes correlates with the use of decimals in the metric system; therefore a dosage should be stated in milliliters as a decimal. When looking at the syringe shown in Figure 18-12, notice the rubber ring. When you are measuring medication and reading the medication withdrawn, the forward edge of the plunger head indicates the amount of medication withdrawn. Do not become confused by the second, bottom ring or by the raised section (middle) of the suction tip. The point where the rubber plunger tip makes contact with the barrel is the spot that should be lined up with the amount desired. Let’s examine the syringes below to illustrate specific amounts in a syringe. The larger hypodermics (5, 6, 10, and 12 mL) are used when volumes larger than 3 mL are desired. These syringes are used to measure whole numbers of milliliters as opposed to smaller units such as a tenth of a milliliter. Syringes 5, 6, 10, and 12 mL in size are calibrated in increments of fifths of a milliliter (0.2 mL), with the whole numbers indicated by the long lines. Figure 18-13, A, shows 0.8 mL of medication measured in a 5-mL syringe, and Figure 18-13, B, shows 7.8 mL measured in a 10-mL syringe. Syringes that are 20 mL and larger are calibrated in whole milliliter increments and can have other measures, such as ounces, on them. A tuberculin syringe is a narrow syringe that has a capacity of 0.5 mL or 1 mL. The 1-mL size is used most often. The volume of a tuberculin syringe can be measured on the milliliter scale. On the milliliter side of the syringe, the syringe is calibrated in hundredths (0.01 mL) and tenths (0.1 mL) of a milliliter. The markings on the syringe (lines) are closer together to indicate how small the calibrations are (Figure 18-14). There are two types of insulin syringes: Lo-Dose and 1-mL size. The Lo-Dose syringe is used to measure small dosages and is 0.5 mL or 0.3 mL in size. It may be used for clients receiving 50 units or less of U-100 insulin. It has a capacity of 50 units. The scale on the Lo-Dose syringe is easy to read. Each calibration (shorter lines) measures 1 unit, and each 5-unit increment is numbered (long lines) (Figure 18-15, B). A 30-unit syringe, which is also a Lo-Dose syringe, is available for use with U-100 insulin only and is designed for small dosages of 30 units or less. Each increment on the syringe represents 1 unit (Figure 18-15, C). A 30-unit insulin syringe is commonly used in pediatrics to administer insulin. The 1-mL size syringe is designed to hold 100 units. There are currently two types on the market. One type of 1-mL (100-unit) capacity has each 10-unit increment numbered. This syringe is calibrated in 2-unit increments (see Figure 18-15, A). Odd-numbered units are therefore measured between the even calibrations. Measurement of dosages that are approximate (in between lines) should be avoided. The second type of 1-mL-capacity syringe has two scales on it. The odd numbers are on the left of the syringe, and the even numbers are on the right. The calibrations are in 1-unit increments. The best method for using this type of syringe is the following: Measure uneven dosages on the left, and measure even dosages using the scale on the right (see Figure 18-16). The calculation of insulin dosages and reading of the calibrations are discussed in more detail in Chapter 20. The diazepam label in Figure 18-17 tells us that the total size of the vial is 10 mL. The dosage strength is 5 mg per mL. The Corvert label shown in Figure 18-18 indicates that the total vial size is 10 mL and there are 0.1 mg per mL.

Parenteral Medications

PACKAGING OF PARENTERAL MEDICATIONS

SYRINGES

Types of Syringes

HYPODERMIC SYRINGES

TUBERCULIN SYRINGE

INSULIN SYRINGES

READING PARENTERAL LABELS

Parenteral Medications

Points to Remember

Points to Remember Practice Problems

Practice Problems

Practice Problems

Practice Problems

Critical Thinking

Critical Thinking Points to Remember

Points to Remember Practice Problems

Practice Problems