Pancreaticoduodenectomy: Pancreaticojejunostomy

Charles M. Vollmer

DEFINITION

Pancreaticojejunostomy is defined as the anastomosis of a remnant pancreas to the jejunum. This is a necessary step in restoring intestinal tract continuity following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD).

Although there are numerous options on how to restore continuity of the pancreas to the enteric tract following PD, central pancreatectomy, or distal pancreatectomy (rarely), pancreaticojejunostomy is the most frequently applied technique worldwide. Furthermore, there are a number of technical variations available for this procedure including “dunking” and “invagination” approaches. This chapter depicts construction of the widely prevalent double-layered, duct-to-mucosa, end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy.

This chapter’s importance lies in the following: Although the first half of PD hinges on the optimal resection of diseased tissue, which determines long-term (usually oncologic) outcomes, the reconstruction phase sets the tone for the immediate postoperative recovery period through the prevention of complications. Chief among these is pancreatic anastomotic failure, which occurs roughly 15% of the time.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

An improved, international consensus definition of this complication has been enthusiastically adopted by most pancreatic surgeons (International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula [ISGPF]).1 Subsequently, patient-specific risk factors for clinically relevant leaks have been identified as (1) soft gland texture, (2) small pancreatic duct diameter, (3) pathology exclusive of pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis, and (4) elevated blood loss.2 These variables are best elucidated at the time of the operation, but preoperative prediction of these important variables is possible, should factor into decision making, and understanding them can influence intra- and postoperative management techniques.3

TECHNIQUES

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Pancreatic Transection

A successful anastomosis begins well before the reconstruction phase of the procedure. Limiting blood loss and careful handling of the pancreas during the resection stage should be regular goals.

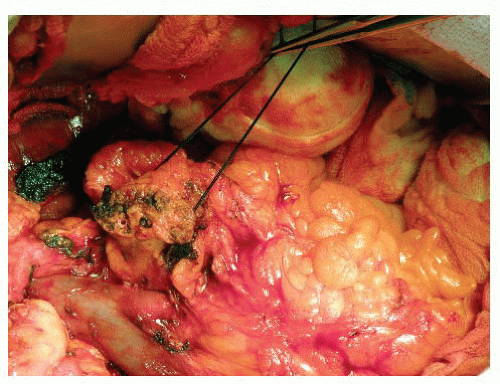

Once an appropriate site of transection over the portal vein (PV) canal is chosen, it is helpful to place hemostatic transfixion sutures on each side of the proposed plane. There are reproducible horizontal arterial arcades a few millimeters within the superior and inferior borders of the pancreas. A 2-0 silk, figure-of-eight suture is deeply placed into each border and on each side of the transection plane (total of four). Care must be taken to not place these too deeply in to the parenchyma on the left (stay) side, such that the pancreatic duct is inadvertently occluded. This is not a concern on the right side where the pancreatic head specimen will ultimately be removed. Once tied down, these sutures are not cut but rather maintained long on a snap to aid in leverage of the distal gland during the reconstruction phase (FIG 1).

Transection can occur via a number of techniques including scalpel or staplers. However, Bovie cautery is preferred for its ability to limit blood loss. A needle-tipped cautery provides good precision with focused coagulation. The cut mode is used to transect the capsule and most of the parenchyma, whereas focal use of the coagulation mode is valuable to control distinct blood vessels when encountered. This approach proceeds through the majority of the gland until the area of the duct is anticipated. Sharp transection of this area is preferred to prevent thermal damage to the duct.

Cautery is then focally applied to dry up any oozing from the cut edge of the pancreas. There is quite often a reproducible arterial vessel on the posterior edge of the gland just beneath where the duct lies.

The distal pancreatic remnant should be elevated off of the splenic vein beneath it for a distance of at least 2 to

3 cm. This, along with traction on the transfixion sutures, will expose the back side of the gland so that the posterior row of the outer anastomotic layer can eventually be created. This is generally an avascular plane until the point where the splenic vein becomes incorporated by pancreatic parenchyma.

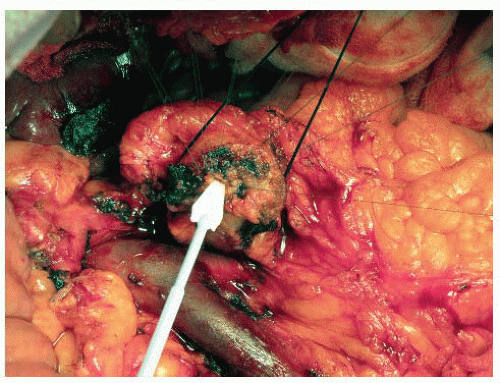

The Setup

Once hemostasis of the pancreatic transection planes is achieved, the pancreaticobiliary drainage limb is introduced to the right upper quadrant (RUQ). Although many achieve this by placing it through the transverse mesentery in a retrocolic position, the author prefers to lay the limb in a completely retromesenteric fashion. The limb is introduced from the infracolic compartment (left side of midline) through the previous ligament of Treitz canal to the RUQ. Once placed in apposition with the remnant pancreas and the transected bile duct, this, in essence, becomes a “neoduodenum” (FIG 2). However, this may also be achieved in the more traditional fashion mentioned earlier, particularly in the cases where the patient has significant central obesity.

Remember the hallmark surgical dictum that the success of an anastomosis is predicated on the following factors: (1) healthy tissue with a good blood supply, (2) lack of tension, and (3) freedom of distal obstruction. You can assure that the pancreaticobiliary drainage limb has a good pulse by palpating the vascular arcade within the mesentery after it has been placed in the desired position. Meticulous technique during the jejunal resection should assure that there is not a mesenteric hematoma, which might compromise the health of the limb. Do not shortchange the amount of proximal jejunum, which is originally resected, as this will shorten the mesenteric “leash” and therefore place tension on the limb as it reaches to the RUQ.

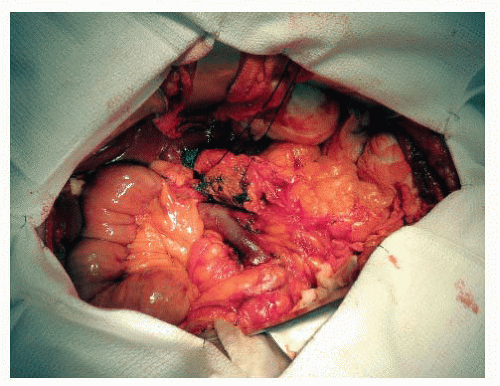

Hemostasis of the transection plane of the neck of the pancreas is achieved by judicious use of the needletipped Bovie cautery on a low power (15 to 20). Energy near the pancreatic duct is avoided.

The pancreatic duct diameter is examined and measured with a flexible ruler. An absorptive “Weck-Cel” arrowhead spear is useful in keeping the duct dry both now, and later, when precision is needed during suture placement in the duct (FIG 3).

The duct can be actively dilated by placing the tips of a fine instrument (Gemini or pediatric right angle) within the duct and gently spreading and holding them open, being careful to not disrupt the duct tissue. Finally, the patency of the course of the pancreatic duct should be assured by advancing a 5- or 8-Fr pediatric feeding tube within the duct in a retrograde manner. These are flexible and safer than a rigid probe, which might be advanced inadvertently through the duct wall and even the parenchyma.

The operative field is then prepared by covering the retraction devices with an arrangement of white towels which, in effect, excludes the retractor from the field and provides a neutral background to better visualize fine, colored monofilament sutures (FIG 4).

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The inner (duct-to-mucosa) anastomosis is constructed with monofilament absorbable suture. A 6-0 caliber is favored for normal to small ducts, but a 5-0 caliber can be used on larger, dilated ducts (≥8 mm). In select circumstances in extremely small diameter ducts (1 to 2 mm), a 7-0 caliber may be necessary. Remember that smaller grade suture has smaller needles, and thus creates smaller puncture holes. Double-armed sutures provide the most flexibility for needle placement, as some sutures are best applied from in to out, whereas others are optimally placed from out to in. This should be determined on a suture-for-suture basis, depending on how the arc of the needle is applied the most effortlessly through the duct.

Due to the precision required for this step, a Castro Viejo needle driver is recommended rather than a bulky, longer driver controlled in the palm. Finer sized ducts (<3 mm) may benefit from the use of Loupe glasses for magnification.

The author routinely avoids placing a pancreatico-enteric stent across the anastomosis, in light of its inefficiency in preventing pancreatic fistula, particularly in high-risk patients.4 However, to increase precision of the needle placement in precarious ducts, some surgeons find value in creating the anastomosis with a small pediatric feeding tube temporarily in place during the anastomotic construction.

THE INNER LAYER—FRONT ROW

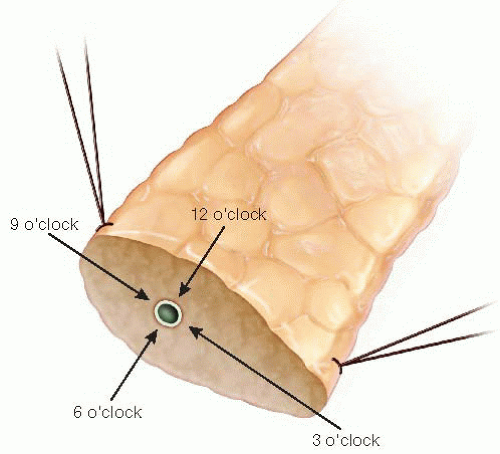

The objective of this step is to “open” the duct orifice and further elevate the face of the transection plane into the field. The appearance of the transected duct can be compared to the face of a clock (FIG 5).

Start by placing the 12 o’clock suture. These needles are curved considerably, and thus, the hand motion should allow for perpendicular placement of the needle tip into the parenchyma about 2 mm behind the duct. A curving motion will deliver it about a millimeter into the duct lumen, where it should be retrieved using a smooth “roll out” motion rather than a “tugging” technique.

The two limbs of the suture are gathered, and the needle from the parenchymal side is removed while the needle attached to the limb emanating from the duct is maintained. A straight snap is used to identify that this is an ordinal point (3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock positions; FIG 5) and is placed off the field in a manner that elevates the pancreas out of the incision slightly.

FIG 5 • Clockface orientation of the pancreatic duct at the transection plane.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access