aBased on 1992 U.S. Vital Statistic Data published by the Institute of Medicine in 1997.

Data from Committee on Care at the End of Life, Institute of Medicine; Field MJ, et al., eds. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

DIAGNOSIS

Palliative care and hospice services involve a multidisciplinary approach to address patient suffering.

Indications for Palliative and Hospice Care

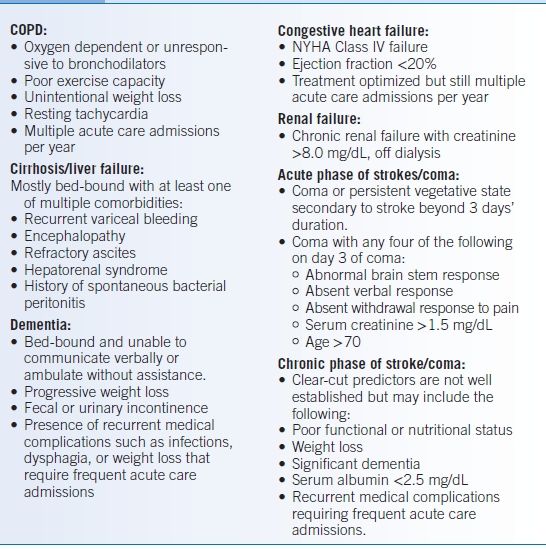

While palliative care consults may be considered at any point during the course of a person’s disease, national guidelines have been established to assist providers with determining when to consider hospice for specific life-limiting noncancer conditions.10 These are detailed in Table 36-2.

TABLE 36-2 Possible Indications for Hospice Care

NYHA, New York Heart Association. Data from Medical guidelines for determining prognosis in selected non-cancer diseases. Hosp J 1996;11:47–63.

Appropriate Timing

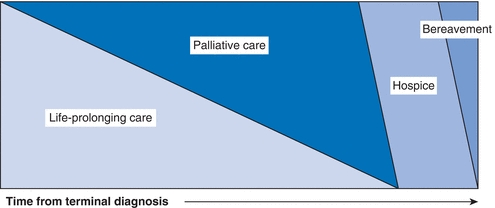

- Appropriate timing for palliative care and hospice interventions is presented in Figure 36-1.

- Palliative care does not exclude the continuation of life-prolonging treatment but rather complements curative therapy by helping clarify goals of care and improving symptomatic control.

- Based on Medicare guidelines, hospice eligibility requires a terminal diagnosis and a life expectancy of <6 months. Patients who live beyond 6 months must be reevaluated by their hospice agency, but may continue in hospice care as long as the conditions of their initial enrollment remain true.

Figure 36-1 Palliative and hospice care in the course of illness. (Adapted from National Consensus Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 2002 and Stanford University Faculty Development Center End-of-Life Curriculum.)

Venues for Palliative and Hospice Interventions

- Palliative care and hospice care may be provided in either inpatient or outpatient settings.

- In the outpatient setting, palliative care may be performed:

- By the primary care provider or treating specialists

- In a palliative care subspecialty clinic by a board-certified palliative care provider and a multidisciplinary group that may involve social workers, chaplains, nurses, and therapists

- By the primary care provider or treating specialists

- Outpatient hospice care can be arranged by a physician by contacting a local hospice organization that serves the patient’s residential area. Admission to hospice does not require a do not resuscitate order and can be concurrent to other therapies.

Goal of Palliative Care

The goal of palliative care is to use the strengths of a multidisciplinary team to improve quality of life for both patient and family in the remaining time a patient has. Specific aims include the following:

- Clarifying patient, family, and care team goals, preferences, and choices

- Providing holistic care of patient and family

- Providing aggressive control of bothersome symptoms

TREATMENT

The principles of palliative care can assist in the following:

- Addressing bothersome symptoms such as pain, nausea, and dyspnea

- Sharing bad news

- Clarifying patient, family, and healthcare provider goals

- Identifying additional stakeholders

- Facilitating discussions to align the goals of care with the treatment plan

Assessing the Experience of the Suffering Patient

- Traditional medical practice views symptoms and signs as evidence of disease. This evidence should disappear once the appropriate diagnosis is made and therapeutic measures initiated.

- The palliative care approach complements traditional models by emphasizing that symptoms themselves are appropriate targets for therapy. It uses the clues that the disease process provides to understand and treat the symptoms.

- Symptoms have both physical and psychological components.

- Physical aspects may be local (what is causing pain) or central (how pain is processed) components.

- Psychological components include affective (how an illness is emotionally experienced), cognitive (what patients understand about their illness), and spiritual (how symptoms are organized by patients into a framework that allows them to understand their illness).

- Physical aspects may be local (what is causing pain) or central (how pain is processed) components.

Steps to Sharing Bad News

- Many physicians have minimal formal training in sharing bad news during their preclinical years and few watch more experienced physicians model such conversations during their clinical rotations.11

- Discussions of bad news frequently involve raw emotion. They are difficult even under the best of circumstances and can be both personally and professionally challenging. Done skillfully, however, they can help patients, families, and health care providers move through difficult situations in a productive manner.

- Traditionally, effective communication has been viewed as something that physicians-in-training absorb through experience as a function of natural aptitude and not as a set of teachable skills. More recently, authors have emphasized that, regardless of affinity, there are several key steps to facilitating conversations about bad news.12

- Preparation is extremely important and includes the following:

- Understanding the medical condition and implications of available therapies and preparing resources if barriers exist.

- Arranging an in-person meeting (if possible) to share the news, along with having a support person available.

- Finding a quiet place and adequate time to sit and talk with minimal distractions. Turning pagers/cell phones to vibrate and instructing support staff not to interrupt, or when possible, including support staff who have a relationship with the patient may be helpful.

- Understanding the medical condition and implications of available therapies and preparing resources if barriers exist.

- Next, making a connection with the person hearing the news is important. This begins with introductions of all parties involved, followed by an assessment of their immediate needs, comfort, and their understanding of the situation.

- Sharing the news involves speaking slowly using clear and unambiguous language, prefacing the news with a statement, such as “I unfortunately have some bad news,” and giving the news briefly.

- After delivering the news, assessment of the reaction is key. A direct question about what the patient or family is thinking may prompt useful dialogue. Respond with brief, simple answers, and recognize that the emotional impact of the bad news may restrict the quantity of information that can be delivered. Follow-up is essential. If the recipient of the bad news is alone, ask whether someone should be called to provide additional support.

- Finally, transition to follow-up by establishing a concrete plan for a future meeting to address additional questions. If a referral is necessary, identify whom that provider will be and how he or she will be contacted. Close the meeting with a statement of concern and commitment to help.

- Preparation is extremely important and includes the following:

- It may be helpful after difficult discussions to debrief with other members of the health care team—pay attention to your feelings and needs as the provider who shares the bad news.

Goals of Care Discussions

Once the initial shock of bad news has subsided, it is important to establish clear goals for care in order to develop a rational therapeutic plan. One algorithm for addressing goals of care discussions is the GOOD acronym, developed as part of the Stanford End of Life Curriculum.13

Goals

- Before the discussion begins, it is essential to identify the stakeholders and assess their understanding of the current situation. The patient and his/her family are obvious stakeholders, but there are frequently many other people as well, including health care providers or members of the community.

- “Big picture goals” about the “who, what, when, and where” of living should be identified first because they provide the context. In addition, most “big picture” goals reveal underlying values that must be understood before moving onto specific aims.

Options

- Next, specific options are discussed by listing them and then narrowing them down by the requests of the involved stakeholders.

- Providers have an important role in discussing the benefits and burdens of the options available.

- Providers can help stakeholders understand the possible outcomes associated with available options.

- Values of the stakeholders are important because they help assign the relative importance of each outcome state.

Opinions

- Offer your opinion in a neutral manner, incorporating earlier data elucidated about patient and family views, clinician goals, benefits and burdens of care, probabilities of outcomes, and the values of the stakeholders involved.

- Many patients are interested to know what their caregivers’ opinions are and, in fact, appreciate information provided along with a recommendation.

Document

- Finally, write a note that includes key information from the meeting including the names and relationships of the participants, decisions regarding the “big picture goals,” the immediate care plan, and the care plan in the event of discussed scenarios.

- It is also helpful to include an assessment of the decision-making process, and whether it makes sense in light of the “big-picture goals.”

Addressing End-of-Life Nutrition and Artificial Nutritional Support

- Many clinicians recommend for or against artificial nutrition on the basis of cultural or personal biases (e.g., fear of starving the patient) rather than medical evidence. A review of the published literature indicates the following:

- Artificial nutrition can improve survival in acute catabolic states such as sepsis or in highly functional patients with advanced proximal gastrointestinal cancer, and in those with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who desire nutrition.14

- Tube feeding does not reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia.15,16

- Tube feeding does not prolong life in those with advanced cancer or dementia.17

- Tube feeding may not improve quality of life and can decrease quality of life by depriving a patient of the pleasure of eating.18

- Parenteral feeding carries risk of fluid overload, line infection, electrolyte imbalances, and hyperglycemia.

- Most actively dying patients do not complain of hunger or thirst, though dry mouth is prevalent.19

- Reduced appetite and weight loss are common in chronic disease.

- Artificial nutrition can improve survival in acute catabolic states such as sepsis or in highly functional patients with advanced proximal gastrointestinal cancer, and in those with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who desire nutrition.14

- Knowing these facts and addressing a patient’s nutritional preferences prior to the occurrence of cachexia or anorexia can reduce patient and family emotional stress and foster acceptance of the dying patient’s altered eating habits.20

- It is important to differentiate between the provision of artificial nutrition and the acts of eating or feeding. Most people enjoy eating (even if only a few bites of their favorite food) and feeding a loved one who is sick can be a significant and pleasant nurturing activity for both patient and family.

- Appetite stimulants may be considered if prognosis is unclear and death not imminent.

- Megestrol 400 to 800 mg/day, medroxyprogesterone 500 mg bid, or dexamethasone 2 to 4 mg bid have shown similar nonfluid weight gains but have no effect on mortality and equivocal effects on quality of life.21

- Mirtazapine should be considered for concurrent cachexia and depression (common in end of life care) with one study showing an average weight gain of 3.9% body weight after 3 months of 30 mg/day; mirtazapine is not recommended in the absence of depression.22,23

- Megestrol 400 to 800 mg/day, medroxyprogesterone 500 mg bid, or dexamethasone 2 to 4 mg bid have shown similar nonfluid weight gains but have no effect on mortality and equivocal effects on quality of life.21

- It is important to validate family members’ concerns, especially in terms of their intent as those who love and care for the patient.

- Acknowledging the difficulty of the situation and the commitment of all concerned to the patient’s well-being may help families make informed decisions regarding end of life nutritional preferences.

Assessing and Managing Nonpain Symptoms

Nausea and Vomiting

- Nausea and vomiting arise from the emetic center in the medulla, which receives input from, and is triggered by multiple sources including the following:

- Gastrointestinal tract (e.g., dysmotility, obstruction, or compression)

- Infection or inflammation (especially involving the gastrointestinal tract)

- Effects of medications that are sensed as toxins in the chemoreceptor trigger zone

- Vestibular instability

- Cognitive and affective components (e.g., environmental clues, underlying depression, or anxiety) that impact the cerebral cortex

- Gastrointestinal tract (e.g., dysmotility, obstruction, or compression)

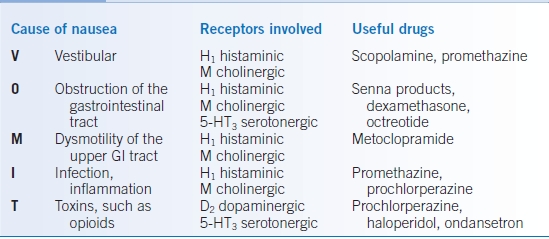

- Understanding the origin of nausea can help to guide more specific and effective therapies based on relative receptor activity and drug targets (Table 36-3).24

- Though the mechanism is unclear, corticosteroids have good antiemetic properties. Steroids, marijuana/dronabinol, and the antidepressant mirtazapine through 5-HT3 and 5-HT2 blockade are used primarily in cancer and chemotherapy-related nausea (see Chapter 35).25

- If nausea or vomiting persists, an agent from a different class should be used rather than one with a similar mechanism of action to minimize side effects.

TABLE 36-3 Antiemetics for Specific Causes

Modified from Hallenbeck J, Weissman D. Fast fact and concept #5: treatment of nausea and vomiting Center to Advance Palliative Care. www.capc.org. Last Accessed 1/12/15.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree