Diagnostic Testing

- No diagnostic test is available to provide objective assessment of pain.

- Diagnostic testing is indicated when the history and physical examination point toward sources of pain, which may be amenable to curative treatment.

- Additional testing is sometimes indicated for pain that may require specialized interventions such as surgery, although a discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this text.

TREATMENT

- A thorough history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests as indicated should identify potentially curable causes of pain. If treatable causes of pain are discovered, pain control should be pursued along with curative therapy.

- When no curable cause of pain is found, therapy should proceed with a combination of nonpharmacologic treatments, medications, and possibly targeted procedures, if applicable.

- All interventions and therapies should be tailored to meet the needs of each patient. Complete relief of pain may not be possible; satisfactory control of pain, however, may allow participation in important activities or other specific goals of the patient.

Historical Perspective

- The World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder, developed in 1982, was the result of a public health initiative designed to provide a framework to improve pain control for patients with cancer worldwide. In this simple algorithm, treatment of pain is addressed in three steps. If pain persists at a given step, treatment is advanced to the next step. All steps recommend the use of adjuvant therapy, if indicated.

- Step 1 (mild pain): Nonopioid analgesic, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Step 2 (moderate pain): Weak opioid +/− nonopioid analgesic.

- Step 3 (severe pain): Strong opioid +/− nonopioid analgesic.

- Step 1 (mild pain): Nonopioid analgesic, such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- The WHO ladder helped change attitudes toward pain management and heightened physician awareness of the importance of pain management.

- With rational pain management, addiction and tolerance are less likely to be clinical problems.9

- While most patients can achieve improved pain relief using this algorithm, the WHO ladder does have limitations.

- It does not include an assessment step.

- It does not take into account targeted therapy for neuropathic pain.

- It does not allow for nonpharmacologic strategies.

- While it is common practice to follow the WHO’s recommendation to combine NSAIDs with opioids, there is no evidence base to support a clinical difference in pain relief when opioids are given in combination with NSAIDs as compared with either drug alone.10

- It does not include an assessment step.

Basic Pain Management Principles

- For acute self-limited pain, short-acting agents can be used as needed.

- Analgesics may be used before engaging in activities that provoke pain, for example, dressing changes or physical therapy.

- For chronic pain, adequate analgesia is best obtained with a combination of long-acting basal pain medication and doses of short-acting medications as needed for breakthrough pain.

- Breakthrough doses should be 5% to 15% of total daily dose.

- Basal dose should be increased in patients consistently requiring >2 to 3 breakthrough doses per day.

- Dose escalation for inadequate pain control should increase the 24-hour dose by 30% to 50%.

- Breakthrough doses should be 5% to 15% of total daily dose.

- While neuropathic pain is responsive to opioid therapy, adjuvant therapy with antidepressants or anticonvulsants may confer additional benefit.11

- Start with the lowest effective dose of medication and titrate up as needed.

- Be careful to avoid acetaminophen overdose when using opioid/acetaminophen combination pills.

Medications

Nonopioid Analgesics

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- NSAIDs exert antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of cyclooxygenase isoenzymes (COX1 and/or COX2 depending on the agent), which leads to decreased production of thromboxane and prostaglandins via the arachidonic acid pathway.

- NSAIDs are effective for mild pain, especially pain with an inflammatory component.

- Most NSAIDs have an analgesic ceiling effect, a dose above which there is little improvement in analgesia, but increased risk of adverse effects.

- These drugs are relatively contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency or with a history of peptic ulcer disease.

- Adverse effects of NSAIDs include gastrointestinal tract bleeding via gastritis or ulcer formation, platelet dysfunction, and renal insufficiency. Aspirin may precipitate bronchospasm in patients with severe asthma.

- Gastrointestinal side effects may be reduced by using proton pump inhibitors or H2-blockers to suppress gastric acid production.

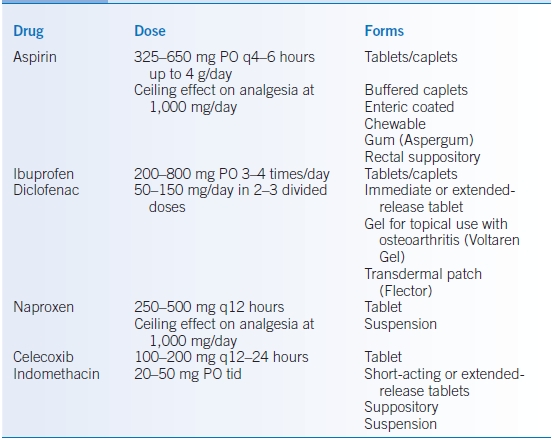

- Details regarding commonly used NSAIDs are presented in Table 37-2.

- NSAIDs exert antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of cyclooxygenase isoenzymes (COX1 and/or COX2 depending on the agent), which leads to decreased production of thromboxane and prostaglandins via the arachidonic acid pathway.

- Acetaminophen

- Acetaminophen exerts analgesic and antipyretic effects. Its exact mechanism of action is poorly understood.

- Analgesic dosing is 325 to 650 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours or 1 g 3 to 4 times/day. Maximum daily dose should not exceed 4 g/day for patients with normal hepatic function; patients with liver disease should not take >2 g/day. The recommended maximum dose for patients >70 years of age is 3 g/day.

- An analgesic ceiling effect likely occurs at doses of 1 g.12

- The major adverse effect of acetaminophen is liver toxicity, ranging from mild transaminitis to fulminant hepatic failure. Patients with underlying liver disease or heavy alcohol use can experience liver damage at lower doses.

- Acetaminophen is available in tablet, oral liquid, intravenous, and suppository forms.

TABLE 37-2 Commonly Used Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- Acetaminophen exerts analgesic and antipyretic effects. Its exact mechanism of action is poorly understood.

Opioids

- Opioids exert analgesic effects to alter pain perception via opioid receptors in both the central nervous system and the spinal cord.

- Unlike other classes of analgesics, opioids have a very large titration range. The analgesic ceiling effect generally occurs only at extremely high doses of opioids.

- Opioids offer flexibility in dosing routes that can be customized to a patient’s needs.

- Doses can be given via oral, transdermal, sublingual, intravenous, rectal, subcutaneous, intrathecal, intraventricular, buccal, and epidural routes.

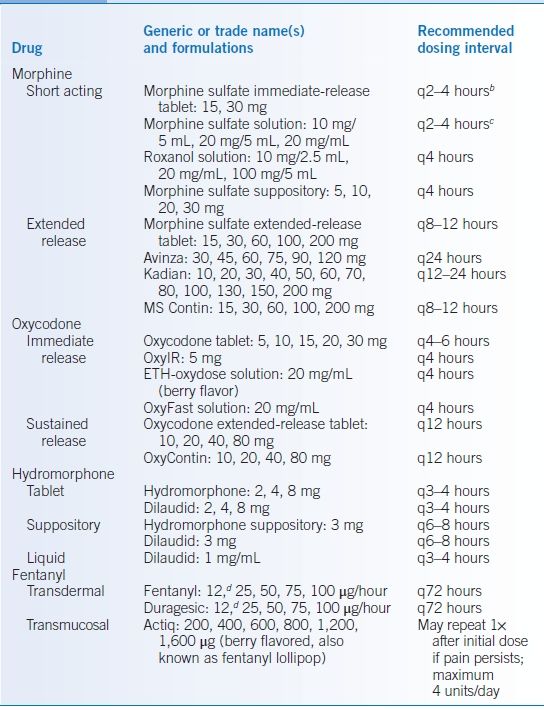

- Refer to Table 37-3 for commonly prescribed opioids and dosing.13

- Data comparing opioid efficacy are limited, and the results are largely equivocal. Opioid selection may be based on desired route of administration, availability, and individual patient tolerance for a given drug.

- Meperidine

- Meperidine is NOT recommended for treatment of pain because of limited efficacy and a very short duration of analgesia with significant euphoria. Historically, it has been a significant prescription drug of abuse.

- Its active metabolite normeperidine accumulates in renal failure and can lower the seizure threshold.

- Meperidine is NOT recommended for treatment of pain because of limited efficacy and a very short duration of analgesia with significant euphoria. Historically, it has been a significant prescription drug of abuse.

- Tramadol

- Tramadol is both an opioid agonist and a centrally acting nonopioid analgesic that acts on pain processing pathways.

- Dosing is 50 to 10 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours. Maximum daily dose is 400 mg/day.

- Side effects include flushing, headache, dizziness, insomnia, somnolence, nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspepsia, and pruritus. Dose titration starting with 25 mg and gradually increasing can improve tolerance.

- Tramadol is metabolized by the liver and excreted largely by the kidneys. It is not dialyzable. It has an active metabolite that can lower the seizure threshold, particularly when taken in combination with some antidepressant medications. It should not be used in patients with known seizure disorders.

- Tramadol is both an opioid agonist and a centrally acting nonopioid analgesic that acts on pain processing pathways.

- Codeine

- Codeine is an opioid prodrug with modest antitussive effects.

- To exert analgesic effect, codeine must be metabolized to morphine by the liver. Up to 10% of the US population lacks the appropriate enzyme for codeine metabolism. In these patients, codeine will provide analgesia similar to acetaminophen, but with higher rates of constipation. Like morphine, its clearance is reduced in the setting of renal impairment.

- Codeine is an opioid prodrug with modest antitussive effects.

- Morphine

- Morphine is often the first-line opioid given its safety profile, ease of use, availability, and physician experience with its use.

- Two active metabolites of morphine can accumulate in renal insufficiency, so alternate opioids may be considered for patients with renal impairment.

- Morphine is often the first-line opioid given its safety profile, ease of use, availability, and physician experience with its use.

- Oxycodone

- While a single meta-analysis found pain control to be slightly better with morphine than with oxycodone, dry mouth and drowsiness were less prevalent with oxycodone.14

- Oxycodone has few renally cleared active metabolites.

- While a single meta-analysis found pain control to be slightly better with morphine than with oxycodone, dry mouth and drowsiness were less prevalent with oxycodone.14

- Hydromorphone

- Available data suggest no significant difference in analgesia or side effects between hydromorphone and other opioids.15

- Hydromorphone has few renally cleared active metabolites.

- Available data suggest no significant difference in analgesia or side effects between hydromorphone and other opioids.15

- Methadone

- Methadone is an opioid agonist as well as an N-methyl-d-aspartic acid antagonist, producing analgesia with additional adjuvant effects for neuropathic pain.

- The half-life of methadone is relatively long and varies significantly between patients. The duration of methadone’s analgesic effect is much shorter than its half-life.

- Methadone interacts with many common medications resulting in further pharmacokinetic variability.

- Methadone has similar efficacy to morphine for cancer pain with similar side effects in short-term studies. However, in long-term studies, methadone side effects were more pronounced.16 In addition, recent data suggest an increase in mortality in patients using methadone, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has urged caution and careful titration of methadone in pain therapy.17

- Methadone can be a very useful drug for chronic pain, but it is best prescribed by physicians experienced with its use. Close follow-up during dose titration is essential.

- Methadone is an opioid agonist as well as an N-methyl-d-aspartic acid antagonist, producing analgesia with additional adjuvant effects for neuropathic pain.

- Fentanyl

- Fentanyl may cause less constipation than other opioids; however, the difference is likely to be small.18,19

- Transdermal fentanyl is best used for stable pain syndromes.

- Fentanyl has no renally cleared active metabolites.

- Fentanyl patch absorption requires skin adhesion and subcutaneous fat. Response is less predictable in patients with cachexia, fever, or diaphoresis.

- Fentanyl may cause less constipation than other opioids; however, the difference is likely to be small.18,19

- Alternative opioid formulations

- Opioid combination pills with acetaminophen or ibuprofen are available in a wide variety of doses, but dose titration is limited by the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Commonly prescribed combination pills are presented in Table 37-4.

- Considerations for patients unable or unwilling to take oral analgesics.

- Transdermal fentanyl is useful if pain is stable.

- Extended-release formulations of any oral opioids must not be chewed or crushed. Special coatings on the tablets or granules slow the medication’s release; destroying the integrity of the coating can result in potentially fatal overdose.

- Liquid formulations of short-acting opioids can be given at scheduled intervals to provide basal analgesia. For example, 10 mg liquid morphine sulfate every 6 hours as basal medication, with 5 mg liquid morphine every 4 hours as needed for breakthrough pain.

- Kadian (morphine sulfate extended release) comes in a capsule that can be opened. The granules must not be crushed but may be sprinkled in water and administered via gastrostomy tube (≥16 French).

- Transdermal fentanyl is useful if pain is stable.

- Opioid combination pills with acetaminophen or ibuprofen are available in a wide variety of doses, but dose titration is limited by the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Commonly prescribed combination pills are presented in Table 37-4.

- Conversion between opioids

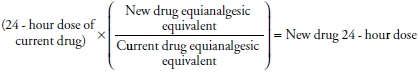

- Use caution when converting between opioids as equianalgesic doses are approximations only (refer to Table 37-5).

- Calculate the 24-hour dose of the current drug.

- Convert this drug to the equivalent dose of the desired new drug with the following equation:

- Reduce dose by 25% to 35% of the calculated new drug equivalent dose to account for incomplete cross-tolerance between opioids.

- Divide the calculated new 24-hour dose by the number of doses planned per day. For example, divide by 2 for twice daily OxyContin or by 4 for doses of oxycodone given every 6 hours.

- If using a basal dose of analgesic, calculate breakthrough doses of the new drug as 5% to 15% of the total daily dose, given at a frequency based on drug half-life.

- Calculate the 24-hour dose of the current drug.

- Ensure that the patient has adequate doses of breakthrough analgesia available when converting between opioids.

- The basal analgesic dose is intentionally reduced during opioid conversion to avoid risks of oversedation and respiratory depression with incomplete opioid cross-tolerance. This means that a patient’s pain may initially be undertreated with the new basal dose.

- Short-acting opioids can be given as frequently as every 2 hours for breakthrough pain during opioid transitions to avoid pain crises in the setting of lowered basal analgesia.

- Patients consistently requiring more than 2 to 3 doses of breakthrough pain medication per day may require an increase in their basal dose.

- Conversion to/from fentanyl

- Use Table 37-6 when converting between fentanyl transdermal patches and oral morphine.

- Increase the dose of fentanyl patch on the basis of the amount of daily breakthrough opioid required.

- Do not titrate patch dose more frequently than every 72 hours.

- Patches may not be cut. The lowest dose fentanyl patch is 12.5 μg/hour.

- Converting to the fentanyl patch: The fentanyl patch takes 8 to 12 hours to reach peak effect, so place the patch at the same time as the last dose of oral long-acting medication is given.

- Discontinuing the fentanyl patch: Remove the patch and start the new extended-release opioid 12 hours later.

- Short-acting oral opioids can be used as needed every 2 hours for breakthrough pain during transitions to and from fentanyl patches.

- Use Table 37-6 when converting between fentanyl transdermal patches and oral morphine.

- Use caution when converting between opioids as equianalgesic doses are approximations only (refer to Table 37-5).

TABLE 37-3 Commonly Prescribed Opioidsa

aOpioids are generally administered intravenously only in the hospital setting, although occasionally they are given subcutaneously in the outpatient setting. This usually occurs in a home hospice setting, and dosing is equivalent to intravenous dosing. Intravenous administration of opioids will not be discussed in this outpatient care manual.

bPeak serum concentration of most short-acting oral morphine preparations occurs after 1 hour. Short-acting doses can be given as frequently as every 2 hours without stacking/overlapping doses. While relatively stable pain is appropriately treated with breakthrough doses every 4 hours as needed, out-of-control pain can be addressed by dosing short-acting opioids every 2 hours.

cInitial dosing of short-acting oral morphine for opioid-naïve patients is 5–10 mg every 4 hours as needed. For an opioid-naïve patient starting oral morphine, solution should be used, as short-acting tablets are only available in 15- and 30-mg formulations.

dDuragesic and fentanyl 12 μg/hour patches actually supply 12.5 μg/hour.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree