33 Pain

Acute pain may be thought of as a physiological process having a biological function, allowing the patient to avoid or minimise injury. Persistent pain, on the other hand, may be described more as a disease than a symptom (Woolf, 2004).

Aetiology and neurophysiology

Neuroanatomy of pain transmission

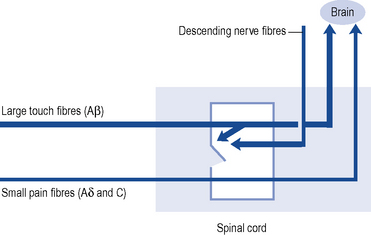

Pain transmission further within the Central Nervous System (CNS) is far more complex and understood less well. The most important parts of this process are the wide dynamic range cells in the spinothalamic tract that project to the thalamus and to the somatosensory cortex beyond. Modulation or inhibition of these neurones within the spinal cord result in less activity in the pain pathway. This modulatory action can be activated by stress or certain analgesic drugs such as morphine and is an important component of the gate theory of pain (Fig. 33.1). The gate control theory recognises the pivotal role the spinal cord plays in the continual modulation of neuronal activity by the relative activity of large (Aβ) and small (Aδ and C) fibres and by descending messages from the brain. Conversely, other influences can lead to an increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli. The most important of these is pain itself and further painful stimuli can lead to increased pain from relatively trivial insults. This occurs through neurochemical and anatomical changes within the CNS that have been termed central sensitisation.

Assessment of pain

Pain is a subjective phenomenon and quantitative assessment is difficult (Breivik et al., 2008). The most commonly used instruments are visual analogue and verbal rating scales. Visual analogue scales are 10 cm long lines labelled with an extreme at each end; usually ‘no pain at all’ and ‘worst pain imaginable’. The patient is required to mark the severity of the pain between the two extremes of the scale. Verbal rating scales use descriptors such as ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ and ‘excruciating’. More elaborate questionnaires such as the Brief Pain Inventory and the McGill Pain Questionnaire help to describe other aspects of the pain, and pain diaries record the influence of activity and medication on pain.

Management

Analgesic ladder

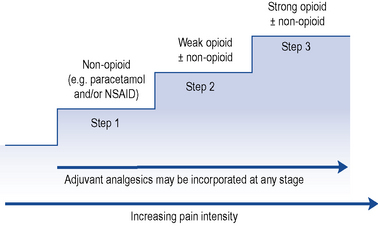

The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (Fig. 33.2) forms the basis of many approaches to the use of analgesic drugs. There are essentially three steps: non-opioid analgesics, weak opioids and strong opioids. The analgesic efficacy of non-opioids, such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g. aspirin, ibuprofen and diclofenac), is limited by side effects and ceiling effects, that is, beyond a certain dose, no further pharmacological effect is seen. If pain remains uncontrolled, then a weak opioid, such as codeine or dihydrocodeine, may be helpful. There may be additional benefit in combining a weak opioid with a non-opioid drug, although many commercial preparations contain inadequate quantities of both components and are no more effective than a non-opioid alone. Strong opioids, of which morphine is considered the gold standard, have no ceiling effect and therefore increased dosage continues to give increased analgesia but side effects often limit effectiveness. Adjuvant drugs, such as corticosteroids, antidepressants or anti-epileptics, may be considered at any step of the ladder.

Analgesic drugs

Paracetamol

Despite being used in clinical practice for over 50 years and much investigation, the mechanism by which paracetamol exerts its analgesic effect remains uncertain. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis within the CNS has been proposed, although this is probably not the only mechanism. Interaction with the serotonin (Tjolsen et al., 1991) and endocannabinoid (Högestätt et al., 2005) neurotransmitter systems have been demonstrated in animal models.

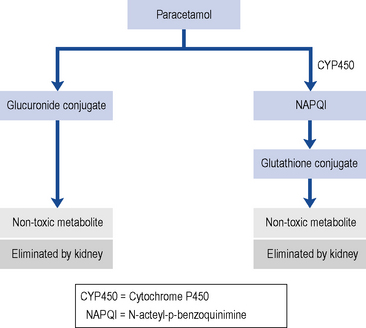

With normal doses, the majority of paracetamols are metabolised and inactivated in the liver, undergoing a phase II conjugation reaction with glucuronic acid (Fig. 33.3). A small P450 mediated reaction that forms a reactive intermediate, N-acteyl-p-benzoquinimine (NAPQI). Usually, NAPQI can be deactivated by conjugation with glutathione in the liver. However, following ingestion of a large amount of paracetamol the hepatic stores of both glucuronic acid and glutathione become depleted leaving free NAPQI, which causes liver damage.

The usual therapeutic dose for adults is paracetamol 1 g taken four times daily. It is very important that this dose is not exceeded, otherwise hepatotoxicity is more common. This may be particularly problematic for malnourished adults with low body weight (Claridge et al., 2010). A reduced maximum daily infusion dose (3 g/24 hours) is recommended for patients with hepatocellular insufficiency, chronic alcoholism or dehydration. Paracetamol is also available as an over-the-counter (OTC) medicine and is a component of many cold and influenza remedies. Compared with other analgesics, paracetamol is not as potent; however, when taken in combination with a NSAID or opioid, there is an additive analgesic effect.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Mode of action

NSAIDs exert their analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects through inhibition of the enzyme cyclo-oxygenase. NSAIDs are used widely to relieve pain, with or without inflammation, in people with acute and persistent musculoskeletal disorders. In single doses, NSAIDs have superior analgesic activity compared to paracetamol (Hyllested et al., 2002). In regular higher dosages, they have both analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects, which makes them particularly useful for the treatment of continuous or regular pain associated with inflammation. NSAIDs have been shown to be suitable for the relief of pain in dysmenorrhoea, toothache and some headaches and to treat pain caused by secondary bone tumours, which result from lysis of bone and release of prostaglandins.

Guidance on NSAID use

The lowest effective dose of NSAID or COX-2 selective inhibitor should be prescribed for the shortest time necessary. The need for long-term treatment should be reviewed periodically. Prescribing should be based on the safety profiles of individual NSAIDs or COX-2 selective inhibitors, on individual patient risk profiles, for example, gastro-intestinal and cardiovascular. Prescribers should not switch between NSAIDs without careful consideration of the overall safety profile of the products and the patient’s individual risk factors, as well as the patient’s preference (Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency, 2006).

Weak opioids

Dextropropoxyphene

Historically, dextropropoxyphene was prescribed in combination with other analgesics such as paracetamol (co-proxamol). There are few data on its therapeutic value, and at least one review concluded that analgesic efficacy is less than aspirin and barely more than placebo. At best, dextropropoxyphene failed to show any superiority over paracetamol (Li Wan Po and Zhang, 1997). At worst, it is a dangerous drug which has the potential for steadily developing toxicity. Patients with hepatic dysfunction and poor renal function are particularly at risk. It is associated with problems in overdose, notably a non-naloxone reversible depression of the cardiac conducting system. Dextropropoxyphene interacts unpredictably with a number of drugs, including carbamazepine and warfarin. In 2005, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) announced concerns about the safety and effectiveness of co-proxamol and directed that it should be withdrawn from clinical use in the UK; however, it still remains available as an unlicensed medicine for the small number of patients who do not obtain analgesia with other analgesic medicines.

Strong opioids

Other strong opioids

The relative potencies of the commonly used opioids are summarised in Table 33.1.

Table 33.1 Relative potencies of opioid drugs

| Drug | Potency (morphine = 1) |

|---|---|

| Codeine | 0.1 |

| Dihydrocodeine | 0.1 |

| Tramadol | 0.2 |

| Pethidine | 0.1 |

| Morphine | 1 |

| Diamorphine | 2.5 |

| Hydromorphone | 7 |

| Methadone | 2–10 (with repeat dosing) |

| Fentanyl (transdermal) | 150 |

Clinical considerations

Use of opioids is almost universally accepted in cancer pain but many patients with persistent non-cancer pain can find considerable relief with strong opioids; however, barriers to their use in this context appear to be based more on ignorance and political fashions than clinical evidence (Ballantyne and Mao, 2003). As a general rule, strong opioids effective in the management of neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain, including osteoarthritis, are less effective for sympathetically maintained pain.

Adverse effects of opioids

Tolerance, dependence and addition

Persistent treatment with opioids often causes tolerance to the analgesic effect, although the mechanism remains unclear (Holden et al., 2005). When this occurs the dosage should be increased or, alternatively, another opioid can be substituted, since cross-tolerance is not usually complete. Addiction is very rare when opioids are prescribed for pain relief.

Smooth muscle spasm

Opioids cause spasm of the sphincter of Oddi in the biliary tract and may cause biliary colic, as well as urinary sphincter spasm and urinary retention. Thus, in biliary or renal colic, it may be preferable to use another drug without these effects. Pethidine was believed to be the most effective in these circumstances but the evidence for this has been questioned (Thompson, 2001).