CHAPTER 6 Outcomes

QUALITY-ADJUSTED LIFE-YEARS (QUALY)

Most QOL measurements are done by questionnaire. The surveys are completed by individuals who have the disease being studied, or by caregivers when the subject is unable to respond. These instruments often use Likert scales to measure graded responses (e.g., poor, fair, good, very good, excellent). They undergo rigorous testing for validity and reliability before they are released for use. Validity addresses the question of whether an instrument measures what is intended. Most methods to check for validity employ another external measure to see how the methods correlate. Reliability is a reflection of reproducibility. A reliable instrument will show some variability but will demonstrate consistency over time.

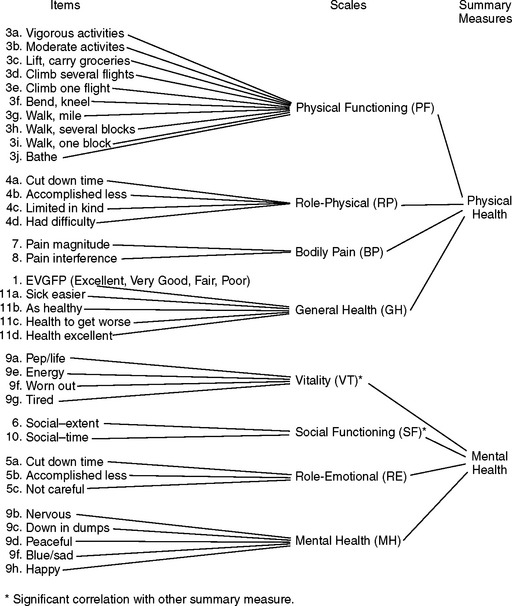

Some surveys cover generic QOL issues, such as the Short Form Health Status Questionnaire, known as the SF-36R. This instrument poses 36 questions that cover multiple health-related categories (also known as domains). These attempt to measure physical, emotional, social, and cognitive levels of functioning. They can therefore be used in various situations to assess general functional status and overall well-being. There are several versions of this type of questionnaire. Figure 6-1 shows a breakdown of the types of domains that are captured in one of these instruments.

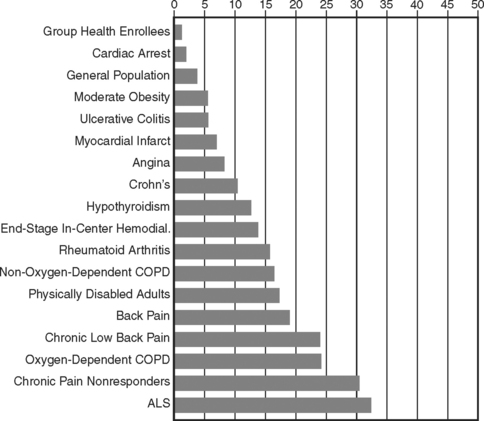

Figure 6-2 shows the results when a cross section of patients with varying types of diseases were asked to evaluate their QOL using a generic measure known as the Sickness Impact Profile score. These are descriptive data that compare different disease states in terms of perceived overall well-being, although the results were not adjusted for age or other factors and the disease states shown are by no means all-inclusive. The longer bars represent poorer QOL perception.

In addition to general QOL measures, other instruments focus on disease-specific issues related to QOL. These are more applicable in chronic, prevalent diseases and can also be used to make comparisons over time within the same sample. For instance, surveys have been developed to measure the QOL experienced by patients with congestive heart failure (CHF.) The often-quoted New York Heart Association classification1 is a simple instrument that assesses the level of symptoms experienced by the individual, using Class I (asymptomatic during normal activities) through Class IV (symptoms occur at rest.) Physicians use this classification to monitor the success of treatment in the individual patient. It is also applied to groups of CHF patients to assess the efficacy of large-scale programs and interventions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree