EAC, external auditory canal; OM, otitis media; TM, tympanic membrane.

TREATMENT

- The EAC should be carefully cleaned by flushing out excess cerumen, desquamated skin, purulent material, and any foreign body, thereby allowing topical treatments to reach the affected skin.

- In advanced cases, proper cleansing may require referral to an otolaryngologist for the use of a binocular microscope and otologic instruments.

- There are a large number of topical otic preparations for treatment: acidifying agents, antiseptics, antibiotics, and corticosteroids, individually or in combination. All appear to have similar efficacy, but antibiotics with or without steroids are most commonly used.4,5

- The most common topical otic antibiotics

- Polymyxin B and neomycin (with 1% hydrocortisone, previously sold under the brand name Cortisporin Otic, now generic, dosed tid to qid). With prolonged use, neomycin may actually cause chronic OE secondary to allergic dermatitis.

- Ciprofloxacin 0.2% (with 1% hydrocortisone, Cipro HC Otic, dosed bid) and 0.3% (with 0.1% dexamethasone, Ciprodex Otic, dosed bid).

- Ofloxacin 0.3% (Floxin Otic, dosed bid).

- Polymyxin B and neomycin (with 1% hydrocortisone, previously sold under the brand name Cortisporin Otic, now generic, dosed tid to qid). With prolonged use, neomycin may actually cause chronic OE secondary to allergic dermatitis.

- Initial duration of therapy is 7 to 10 days, but that can be extended if the infection is not resolved. To deliver drops, another person should fill the EAC with drops while the patient lies with the infected ear up, and some gentle tragal manipulation can help the drops disperse throughout the EAC.

- Antibiotics are clearly better than placebo, and no single antibiotic has been clearly shown to be superior to any other. However, those treated with a quinolone may improve somewhat faster than those treated with a nonquinolone.4,5

- The addition of oral antibiotics is usually unnecessary except in patients with diabetes, immunodeficiency, or infection beyond the EAC.

- The addition of topical steroids to topical antibiotics does not seem to substantially improve clinical cure rates, though they may speed pain relief.

- When there is a suspected or known TM rupture, ototoxic agents (alcohol, acidifiers, Cortisporin, and aminoglycosides) should not be used. Ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin/dexamethasone are approved for middle ear use.4

- If the EAC is significantly narrowed because of edema, topical therapy may be difficult to deliver and a wick (Otowick, Merocel, or ribbon gauze) should be placed. The wick should be gently inserted into the EAC to provide a conduit for the antibiotic drops. As the edema recedes, the wick can be removed, usually after 24 to 72 hours.

- Otomycosis treatment is with acidifying drops such as 50% white vinegar solution, aluminum sulfate-calcium acetate (Domeboro), or antifungals solutions (clotrimazole, Lotrimin).

- Necrotizing OE requires hospital admission with otolaryngology consultation, topical and intravenous high-dose antipseudomonal antibiotic therapy, and ear cleaning, and occasionally, surgical debridement is required.

Otitis Media

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- OM is inflammation of the middle ear.

- Acute otitis media (AOM) is defined by the presence of middle ear effusion with acute symptoms and signs of illness and middle ear inflammation.6 It is an infectious process caused by viruses or bacteria and is far more common in young children than adults, but it does occur in adults.

- The most common viruses are rhinoviruses, influenza viruses, adenoviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus.

- The most common bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.7

- AOM is generally thought to be preceded by inflammation of the upper respiratory tract (e.g., a viral infection or allergic) resulting in obstruction of the isthmus of the eustachian tube (ET). Fluid accumulates in the middle ear due to negative pressure, with subsequent growth of microorganisms.

- The most common viruses are rhinoviruses, influenza viruses, adenoviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus.

- Otitis media with effusion (OME, otherwise known as serous otitis) is a chronic form of middle ear inflammation with a persistent effusion without acute signs of infection.

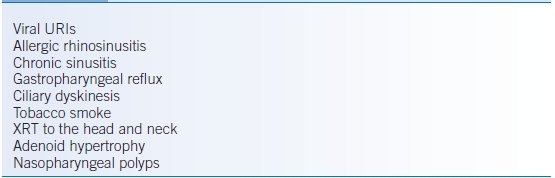

- The ET, which is responsible for ventilation of the middle ear, is normally closed at rest, but opens during swallowing or autoinsufflation (Valsalva maneuver). Apart from AOM and OME, difficulty opening the ET, termed eustachian tube dysfunction (ETD), can result in long-term negative middle ear pressure, causing thinning and inward collapse (atelectasis) of the TM, hearing impairment, difficulty with pressure changes (flying or scuba diving), and potentially cholesteatoma.8 Causes and risk factors for ETD are presented in Table 40-2.

TABLE 40-2 Causes and Risk Factors for Eustachian Tube Dysfunction

URI, upper respiratory infection; XRT, radiation therapy.

DIAGNOSIS

- The most common symptoms of AOM are abrupt onset of otalgia, hearing loss, and occasionally fever.

- OME typically presents with ear fullness and hearing loss. Symptoms of acute infection like pain are absent.

- Otorrhea may develop if there is a TM perforation, which can be caused by excessive middle ear pressure.

- Otoscopy during AOM will show a bulging, sometimes erythematous, opaque TM with decreased mobility on pneumatic otoscopy. Normal middle ear landmarks, like the incudostapedial joint, will be obscured. Yellow purulent fluid is present behind the TM. Viral infection can display vesicles or bullae on the TM (bullous myringitis).

- Otoscopy during OME will show an opaque TM with decreased mobility, loss of middle ear landmarks, possibly air-fluid level or bubbles, or a TM with a radially injected vascular pattern. A clear effusion in the middle ear can be harder to visualize than a colored effusion (typically amber).

TREATMENT

- Acute otitis media

- There are no evidence-based treatment recommendations specifically for adults with AOM. The recommendations here are based on those for pediatric patients.6

- Observation of otherwise healthy patients with mild-to-moderate uncomplicated AOM for 2 to 3 days is appropriate.6

- Antibiotic therapy may be helpful for those who are initially severely symptomatic or for those with persistent symptoms after 2 to 3 days.

- Amoxicillin 500 mg tid for 5 to 10 days is a reasonable first-line choice for the majority of patients.6

- Alternative first-line antibiotics include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole DS, 1 bid; azithromycin, 500 mg qd; or clarithromycin, 500 mg bid.

- When patients fail to respond to first-line treatment or when there are significant concerns regarding resistance, amoxicillin-clavulanate, 875 mg bid, or cefuroxime axetil, 500 mg bid, may be used.

- Tympanocentesis, performed by an otolaryngologist, for culture is rarely necessary but may be helpful in immunocompromised patients, patients whose symptoms fail to respond, or patients in whom complications of AOM, such as intracranial infection, develop.

- There are no evidence-based treatment recommendations specifically for adults with AOM. The recommendations here are based on those for pediatric patients.6

- Otitis media with effusion

- Because OME is not itself an infectious process, antibiotic therapy is usually not indicated.

- Autoinsufflation (Valsalva maneuver), where air is forced up the ET by exhaling against a closed mouth and pinched nostrils, may be beneficial.9

- Watchful waiting is a reasonable approach in the majority of adults. Referral to an otolaryngologist if persistent effusion after 2 to 3 months is reasonable for examination of the nasopharynx for an anatomic obstruction, like a tumor, and to consider ear tube placement.

- Antihistamines, decongestants, and nasal corticosteroids are of uncertain efficacy with regard to OME.10,11

- Because OME is not itself an infectious process, antibiotic therapy is usually not indicated.

- The treatment of ETD most often involves treatment of the underlying cause (Table 40-2), including decongestants and antihistamines.8 There is no evidence in humans that systemic steroids are effective; however, topical nasal steroids would be appropriate for ETD thought due to allergic rhinitis. Surgical treatments are possible but uncommonly used.

Tinnitus

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Tinnitus is a very common and oftentimes very bothersome complaint and is defined as the perception of sound that is not related to any external source. It can affect one or both ears and can be intermittent or continuous.

- Objective tinnitus refers to sounds arising from within the body that an examiner can also perceive. It is usually secondary to turbulent blood flow through vessels near the ear and is often pulsatile. Rarely, it can be caused by myoclonus of palatal or middle ear muscles, producing a clicking sound.

- Subjective tinnitus, on the other hand, is the perception of sound in the absence of an actual acoustic stimulus (internal or external). Subjective tinnitus is much more common than objective tinnitus.

- Prevalence of tinnitus increases with age. Tinnitus is often associated with hearing loss.

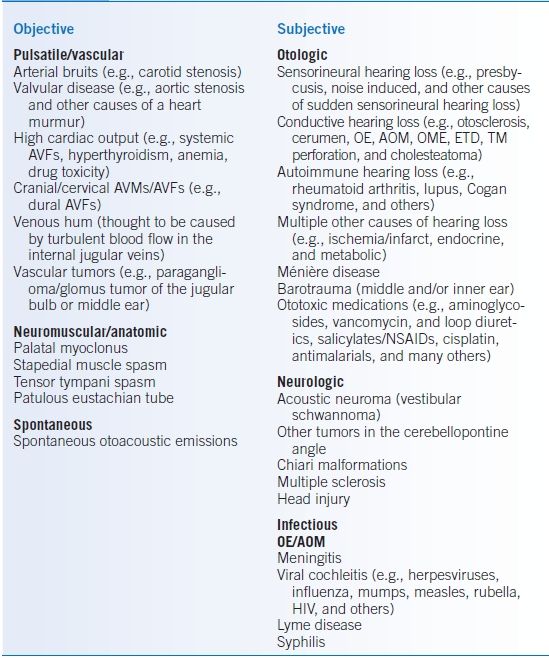

- There are many potential etiologies, some of them quite serious, but the cause is benign in the overwhelming majority of patients (Table 40-3).12

TABLE 40-3 Causes of Tinnitus

AOM, acute otitis media; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; ETD, eustachian tube dysfunction; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OE, otitis externa; OME, otitis media with effusion; TM, tympanic membrane.

Data from Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Burkard RF. Tinnitus. N Engl J Med 2002;347:904–10.

DIAGNOSIS

- Tinnitus may be described by patients in many ways including pulsing, humming, rushing, whooshing, clicking, cricket-like ringing, buzzing, hissing, whining, whistling, and high or low pitched.

- Particular attention should be paid to the otologic history including hearing loss, noise exposure, history of ear infections or ear surgery, cerumen impaction, vertigo, focal neurologic deficits, and exposure to ototoxins.

- Some patients with bothersome tinnitus have significant quality of life impairment, including sleep disturbance, impaired concentration, and mood alterations; they may require more aggressive treatment.

- Perform a head and neck exam, including otoscopy, neurologic exam including the cranial nerves, auscultation around the ear and of the carotid artery, and cardiac auscultation. Glomus tumors, which can cause pulsatile tinnitus, can be seen as reddish masses present inferiorly in the middle ear space.

- Audiometry will be indicated for most patients.

- In patients with a straightforward cause for the tinnitus (e.g., symmetric high-frequency hearing loss in a patient with noise exposure), no further workup is required. Referral to an otolaryngologist is appropriate when other abnormalities are seen on audiogram or there is evidence of objective tinnitus not clearly due to carotid stenosis, heart murmur, or a high flow state.

- Imaging of the brain should be undertaken in patients with focal neurologic signs.

TREATMENT

- Objective tinnitus, while much less common, may be amenable to specific therapies, such as surgery, to correct the underlying cause.

- Competing environmental sounds can mask the tinnitus. Common choices for masking include background noise including music, television, or a room fan. This strategy is especially useful for patients with difficulty sleeping.

- Masking devices are sometimes used to provide relief from intractable tinnitus. These are essentially sound generators worn like a hearing aid that produce low-level broadband noise and are available from audiologists. There are limited data on their effectiveness.13

- Drugs that are known to cause tinnitus, such as aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aminoglycosides, and heterocyclic antidepressants, should be discontinued, if possible. In addition, stimulants like caffeine, nicotine, and decongestants should be avoided.

- Many medications have been studied as treatments for tinnitus, including benzodiazepines, gabapentin, melatonin, and antidepressants.14–16 While none have been clearly shown to be effective in eliminating tinnitus, in some patients, they do provide some benefit. Of those, melatonin has minimal side effects and is a reasonable option for patients with sleep disturbance from tinnitus.

- Tinnitus retraining therapy, which includes counseling and sound therapy several hours a day, may be helpful. The goal is to habituate the patient to the sound and to decrease its negative associations.17

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy may be helpful as well, especially in patients with underlying psychiatric disease.18

Vertigo

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Dizziness is a nonspecific term, and further characterization as vertigo, presyncope, or disequilibrium is helpful.

- Characteristics of vertigo help distinguish between central or peripheral causes.

- The most common peripheral causes of vertigo include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière disease, and vestibular neuritis.

- BPPV is caused by loose particles (otoliths) in the semicircular canals (usually posterior canal).

- Ménière disease is thought to be caused by elevated fluid pressures in the inner ear (endolymphatic hydrops).

- Vestibular neuritis is thought to be caused by inflammation of the vestibular nerve.

- BPPV is caused by loose particles (otoliths) in the semicircular canals (usually posterior canal).

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Try to determine whether the dizziness is vertigo (the illusion of movement of self or environment), disequilibrium (general imbalance), or presyncope (patient feeling like he or she is going to pass out).

- If the patient has vertigo, ask about onset, triggers, duration of each episode, frequency of episodes, and associated symptoms (headaches, hearing loss, tinnitus, ear fullness, otalgia, postural instability).

- Look for red flags such as focal neurologic signs that may suggest stroke or brain lesion.

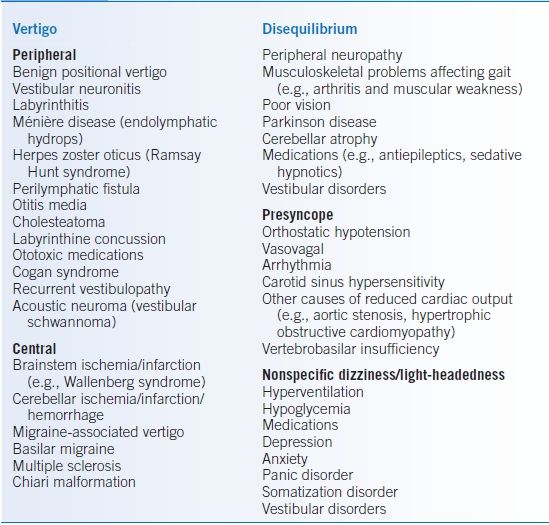

- Table 40-4 lists causes of vertigo, and Table 40-5 lists characteristics of each.19

- BPPV: Sudden, intense vertigo lasting for seconds triggered by laying head back to one side or looking up.20

- Ménière disease: Intermittent vertigo lasting minutes to hours, without a clear trigger, typically associated with unilateral aural fullness, tinnitus, and fluctuating hearing loss.

- Vestibular neuritis: Severe sudden vertigo lasting for days associated with nausea and vomiting. If this is accompanied by sudden hearing loss, it is classified as labyrinthitis.

- BPPV: Sudden, intense vertigo lasting for seconds triggered by laying head back to one side or looking up.20

TABLE 40-4 Causes of Dizziness and Vertigo

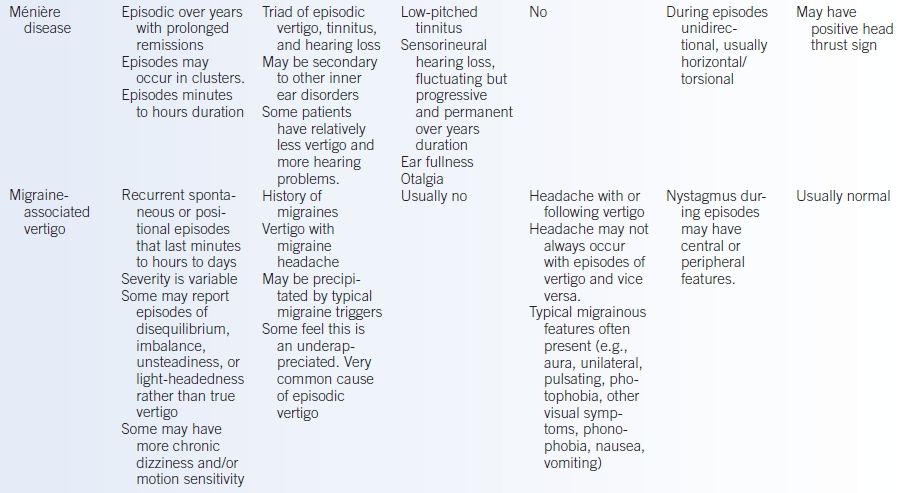

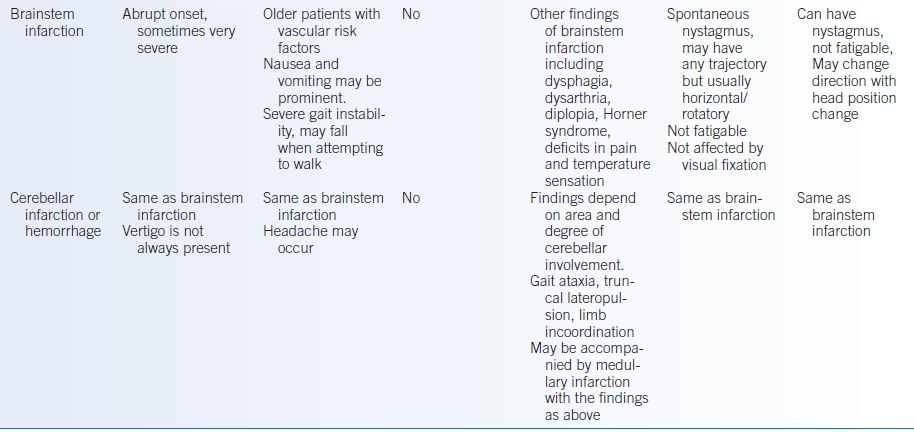

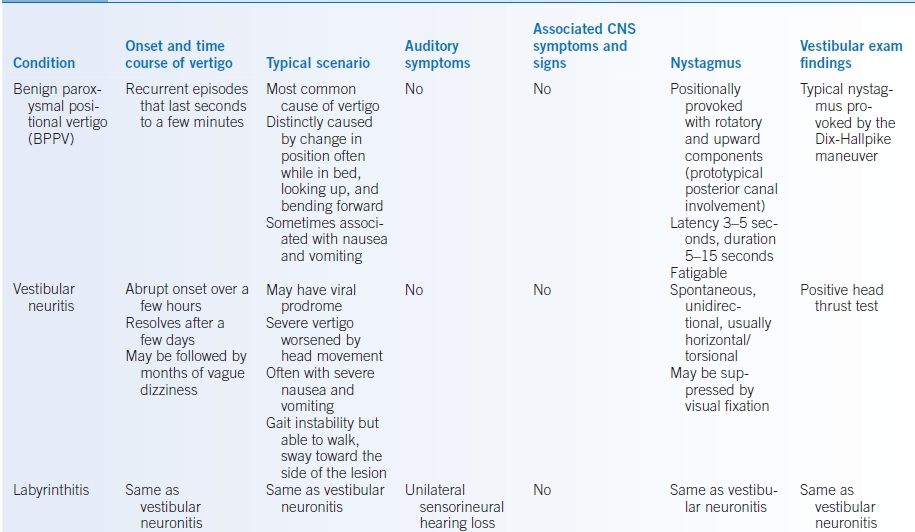

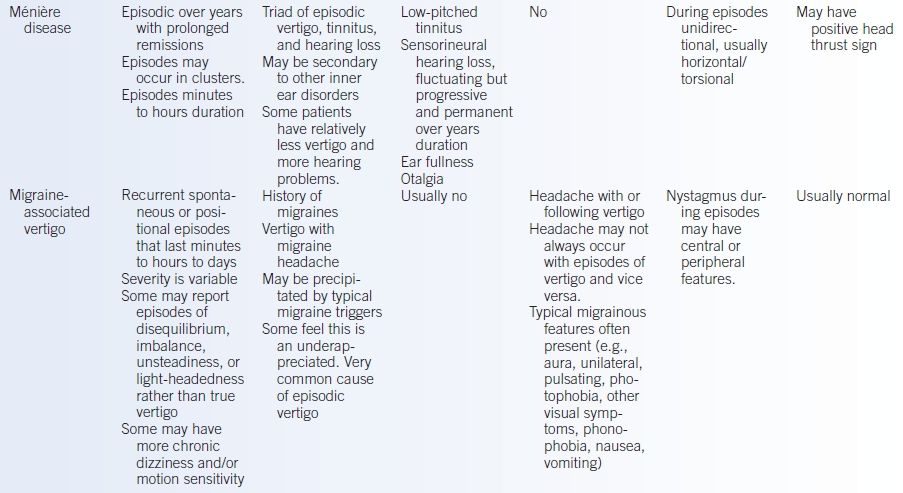

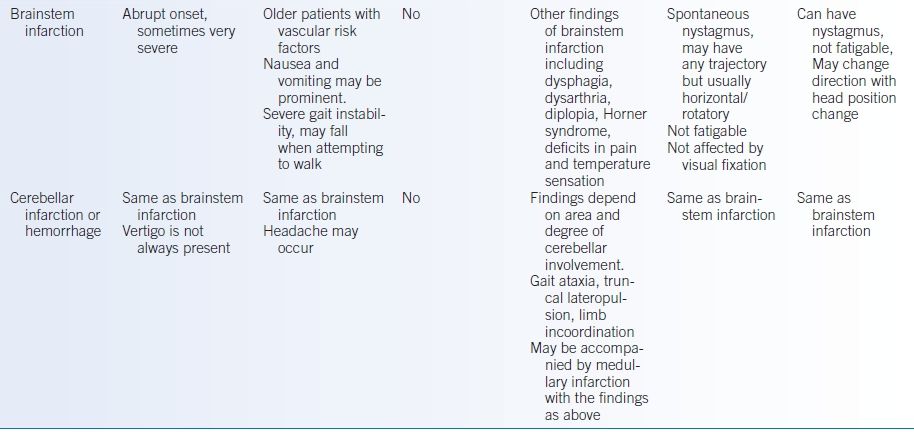

TABLE 40-5 Clinical Features of Common Causes of Vertigo

Physical Examination

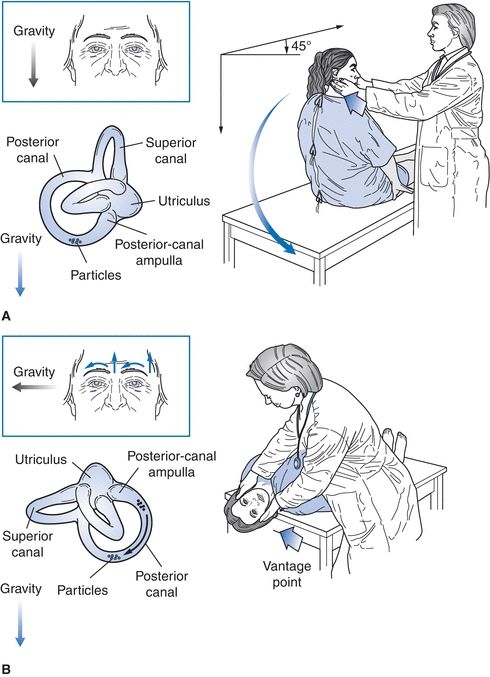

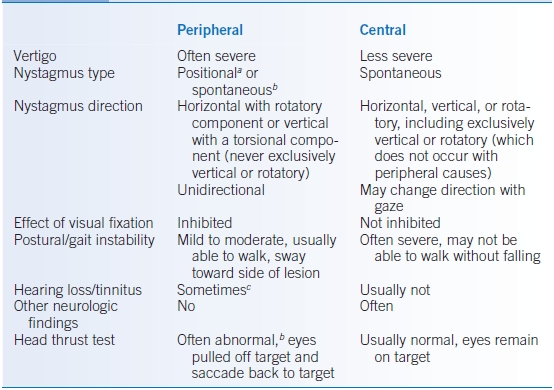

- The goal of the exam is to determine whether the vertigo is peripheral (inner ear) or central (brain) (Table 40-6). The exam should include a full cranial nerve exam, otoscopy, and careful evaluation of the eyes for nystagmus in the following situations: looking straight ahead, gazing 30 degrees left and right, and while performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Fig. 40-1).20

- In BPPV, rotary nystagmus may be observed with the head turned toward the affected side during the Dix-Hallpike maneuver.

- In Ménière disease, the physical exam is often normal with the exception of possible hearing loss.

- In vestibular neuritis, there is a mostly horizontal nystagmus that beats away from the affected ear.

- Table 40-5 provides additional details along with findings seen with stroke and migraine.19

Figure 40-1 Dix-Hallpike maneuver. (From Furman JM, Cass SP. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1590–1596, with permission.)

TABLE 40-6 Distinguishing Peripheral and Central Vertigo

aBenign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière disease, and migraine-associated vertigo.

bVestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis.

cLabyrinthitis, Ménière disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree