(1)

Department of Pathology, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, UK

Abstract

This chapter deals with uncommon primary cervical neoplasms. Tumours covered in this chapter include neuroendocrine neoplasms of which the most common are small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Transitional tumours and various mesenchymal, mixed epithelial and mesenchymal, melanocytic and haematopoetic neoplasms are also covered.

Keywords

Neuroendocrine carcinomaTransitional cell carcinomaMesenchymal neoplasmsMalignant melanomaMalignant lymphomaIntroduction

Apart from squamous carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma, other primary cervical epithelial neoplasms are uncommon or rare. The most prevalent are neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms (mixed Mullerian tumours) occur in the cervix but much more uncommonly than in the uterine corpus. Pure mesenchymal neoplasms, especially smooth muscle tumours, also occur in the cervix, as do rarely lymphoid and melanocytic lesions and a variety of other uncommon neoplasms. These various neoplasms are discussed in this chapter.

Neuroendocrine Neoplasms

Definition and General Comments

The current 2003 World Health Organization (WHO) classifies cervical neuroendocrine neoplasms as carcinoid tumour, atypical carcinoid tumour, small cell carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) [1]. The term small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC) is preferred rather than small cell carcinoma (see below). The WHO classification is identical to the classification currently employed for pulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms but different than that used for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours where the terms grade 1, 2 and 3 neuroendocrine tumour are used. In the cervix, SCNEC is the most common of these neoplasms followed by LCNEC; carcinoid and atypical carcinoid are extremely rare and are morphologically identical to the corresponding neoplasms in other organs [2–8]. It is recommended that the term SCNEC should be used rather than simply small cell carcinoma since a small cell variant of squamous carcinoma exists and use of the term small cell carcinoma can result in confusion. This is important since the management of SCNEC and LCNEC differs significantly from non-neuroendocrine carcinomas. For example, if a diagnosis of SCNEC or LCNEC is made on a biopsy specimen, surgical resection will generally not be undertaken even if the tumour is small and clinically and radiologically confined to the cervix. In addition, the chemotherapy regime will include specific agents which are active against neuroendocrine carcinomas and prophylactic cranial irradiation may be administered.

Cervical SCNEC and LCNEC are HPV-associated neoplasms, the most common HPV types being 16 and 18; in most studies, HPV18 has been more common than 16 [6, 8]. There is a definite association between cervical neuroendocrine carcinomas and premalignant or malignant endocervical glandular lesions; foci of CIN or squamous carcinoma are also occasionally present. Occasional neoplasms are composed of an admixture of SCNEC and LCNEC and in some cases, the morphological features are such that it may be difficult to categorise an individual neoplasm as SCNEC or LCNEC. LCNEC is likely underdiagnosed and may be misclassified as poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, since the pathologist may not think of the diagnosis and fail to perform appropriate immunohistochemical studies.

Morphological Features of SCNEC

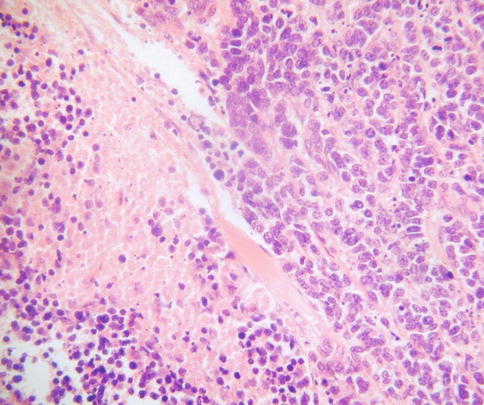

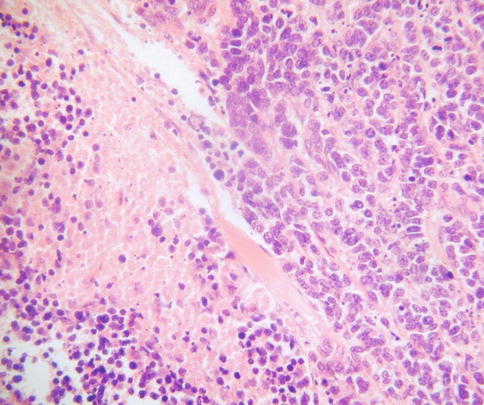

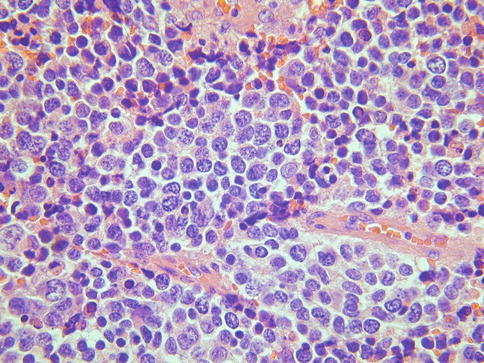

SCNEC is characterised by the presence of a monotonous population of cells with ovoid or slightly spindled hyperchromatic nuclei, often exhibiting moulding, and scanty cytoplasm (Fig. 5.1). There is usually abundant mitotic and apoptotic activity. There may be extensive crush artefact, nuclear fragmentation and necrosis. The growth pattern is usually predominantly diffuse but nests, trabeculae, glandular and rosette-like structures are sometimes present. As discussed, a premalignant or malignant endocervical glandular lesion may also be present (Fig. 5.2) and more uncommonly there is a component of CIN or squamous carcinoma.

Fig. 5.1

Cervical small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma composed of cells with scant cytoplasm. There is nuclear moulding and necrosis

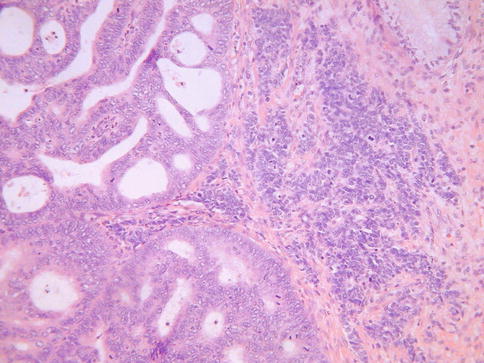

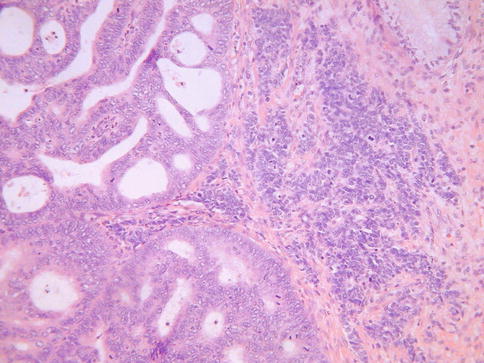

Fig. 5.2

Combined cervical small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma

Morphological Features of LCNEC

LCNEC, as defined by Travis et al. [9] for the corresponding pulmonary tumours, is characterised by:- (a) cells of large size, polygonal shape and low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, (b) nuclei with coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli, (c) mitotic activity in excess of 10 per 10 high power fields, (d) immunohistochemical or ultrastructural evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation. Insular, nested, trabecular, glandular and solid growth patterns are often present, either alone or in combination (Fig. 5.3). There is often extensive geographic necrosis. Nuclear palisading may be apparent around the periphery of cell nests and eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules are present in some cases. A premalignant or malignant squamous or glandular lesion may be present and occasionally there is a component of SCNEC. It should be noted that, analogous to the situation in other organs, small numbers of neuroendocrine cells, as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry, may be present in cervical squamous carcinomas and more commonly in adenocarcinomas, especially when poorly differentiated [10, 11], and this does not justify a diagnosis of LCNEC.

Fig. 5.3

Cervical large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma composed of cells with abundant cytoplasm and an organoid growth pattern

Immunohistochemistry

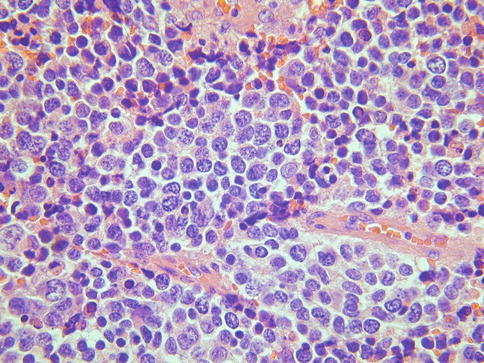

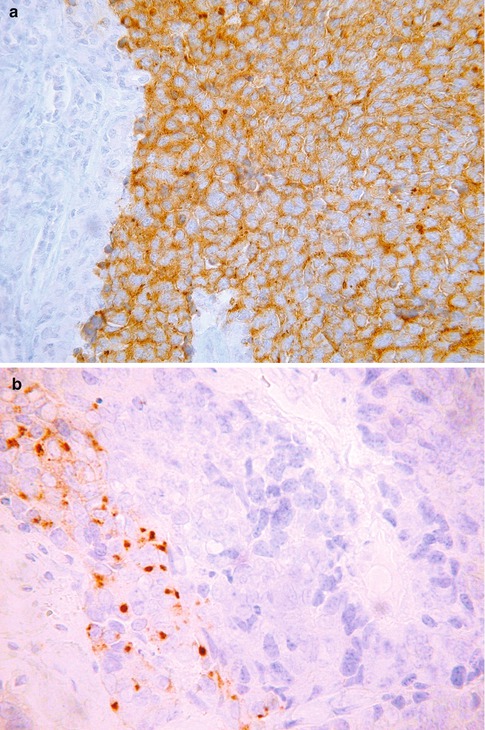

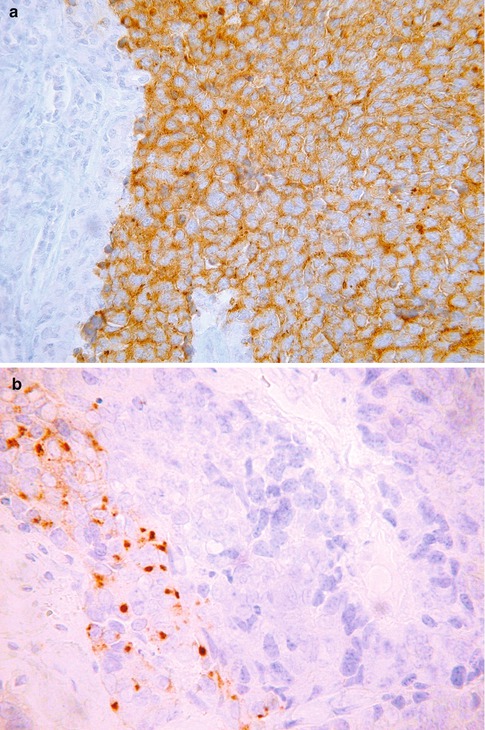

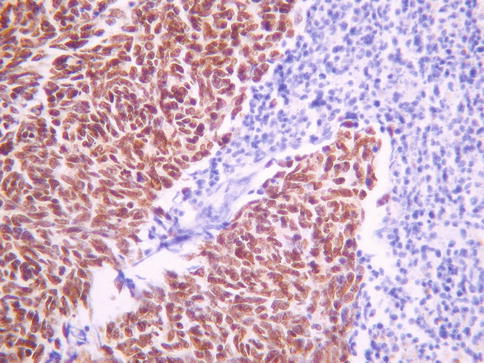

SCNEC is variably positive with the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin, CD56, synaptophysin and PGP9.5 (Fig. 5.4a). Of these, CD56 and synaptophysin are the most sensitive but CD56 lacks specificity. Chromogranin is the most specific neuroendocrine marker but lacks sensitivity with only about 50 % of these neoplasms being positive [12]. Chromomogranin positivity may be very focal with punctuate cytoplasmic immunoreactivity which is only visible on high power magnification (Fig. 5.4b). A diagnosis of SCNEC can be made in the absence of neuroendocrine marker positivity if the morphological appearances are typical. SCNEC may be only focally positive (often punctuate cytoplasmic staining) or even negative with broad spectrum cytokeratins. A diagnosis of LCNEC requires neuroendocrine marker positivity and most of these neoplasms are diffusely positive with broad spectrum cytokeratins.

Fig. 5.4

Cervical small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma exhibiting diffuse cytoplasmic staining with synaptophysin (a) and focal punctuate cytoplasmic staining with chromogranin (b)

A high percentage of primary cervical SCNEC and LCNEC are TTF1 positive, including some with diffuse immunoreactivity (Fig. 5.5), and this marker is of no value in distinction from a pulmonary metastasis [12, 13]. Most SCNEC and LCNEC are diffusely positive with p16 secondary to the presence of high risk HPV [12]. Diffuse p63 nuclear positivity is useful in confirming a small cell variant of squamous carcinoma rather than SCNEC [14, 15]. However, occasional SCNEC and LCNEC exhibit p63 nuclear immunoreactivity [12]. Some SCNEC and LCNEC are positive with CK7, CK20, neurofilament or CD99; such aberrant staining reactions may result in misdiagnosis as a Merkel cell carcinoma or a tumour in the Ewing family [12]. Peptide hormones, including ACTH, serotonin, somatostatin, calcitonin, glucagon and gastrin, have been demonstrated in some of these neoplasms [7].

Fig. 5.5

Cervical small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma exhibiting diffuse nuclear staining with TTF1

Prognosis

Cervical neuroendocrine carcinomas of small cell and large cell type are highly aggressive neoplasms with a propensity for widespread systemic metastasis; even neoplasms with a minor component of SCNEC or LCNEC may behave aggressively. The overall prognosis is poor with survival rates of 25–35 % [2–8]. Involvement of regional and distant lymph nodes, lung, liver, bone and brain is common.

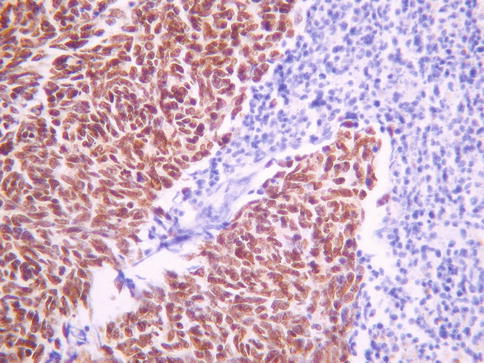

Transitional Neoplasms

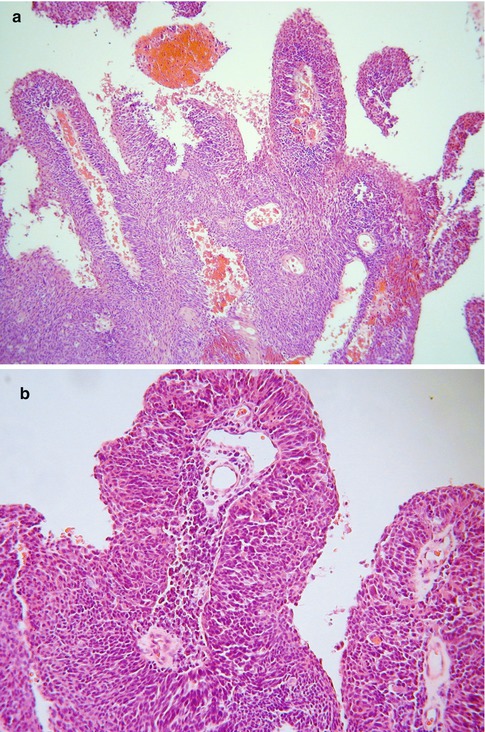

Occasional cervical neoplasms morphologically resemble transitional cell tumours of the urological tract. These usually take the form of papillary neoplasms which are similar to papillary transitional cell carcinomas of the urological tract [16–18]. These have been variously termed papillary transitional cell carcinoma or papillary squamotransitional carcinoma. Morphologically they are composed of broad papillary arrangements of stratified epithelium (Fig. 5.6a) sometimes, but not always, with relatively bland nuclear features (Fig. 5.6b). Nuclear grooves may be present and there can be evidence of squamous differentiation in the form of keratinisation. Rare neoplasms have also exhibited glandular differentiation [19]. Often these neoplasms are entirely located on the mucosal surface with no underlying stromal invasion, although this is not always the case. These are usually HPV related neoplasms, most commonly type 16. Given the close morphological overlap between transitional and squamous epithelium, it is likely that these are related to papillary squamous carcinomas and in some cases the distinction between a papillary variant of squamous carcinoma, squamotransitional carcinoma and transitional carcinoma will be subjective. Occasional invasive cervical carcinomas with transitional features and high grade cytology have been reported but these may simply be unusual variants of squamous carcinoma [17]. A cervical neoplasm morphologically resembling inverted transitional papilloma of the urinary bladder has been reported (Fig. 5.7); both this neoplasm and a similar vaginal lesion contained HPV 42 [20].

Fig. 5.6

Papillary transitional carcinoma of cervix with broad papillary arrangements of epithelial cells (a). On higher power examination, the nuclear features are relatively bland (b)

Fig. 5.7

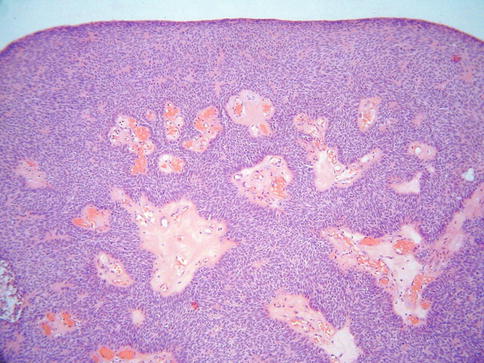

Cervical neoplasm resembling inverted transitional papilloma of urinary tract

Mesenchymal Neoplasms

Mesenchymal neoplasms are much more uncommon in the cervix than in the uterine corpus and some involve the cervix by direct spread from the corpus.

Smooth Muscle Neoplasms

Leiomyomas are by far the most common mesenchymal neoplasm to occur within the cervix but are much more uncommon than in the uterine corpus. The morphological features are usually those of a typical leiomyoma but compared to their counterparts in the corpus, cervical leiomyomas are more likely to exhibit nuclear palisading, reminiscent of a neurilemmoma (“neurilemmoma-like” leiomyoma or “schwannoma-like” leiomyoma) (Fig. 5.8). Leiomyoma variants, similar to those occurring in the corpus, also occur in the cervix. Leiomyosarcomas, including epithelioid and myxoid variants, occasionally occur as primary cervical neoplasms.

Fig. 5.8

Leiomyoma of cervix exhibiting nuclear palisading, in keeping with “neurilemmoma-like” leiomyoma

Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (sarcoma botryoides) occurs as a primary cervical neoplasm, most commonly in the late teens and early twenties (mean age 18 years), although the age range is relatively wide [21–25]. The usual presentation is vaginal bleeding or a mass protruding from the introitus. There is a rare association between cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumour and pleuropulmonary blastoma and this is thought to be due to underlying DICER1 mutation [24, 26].

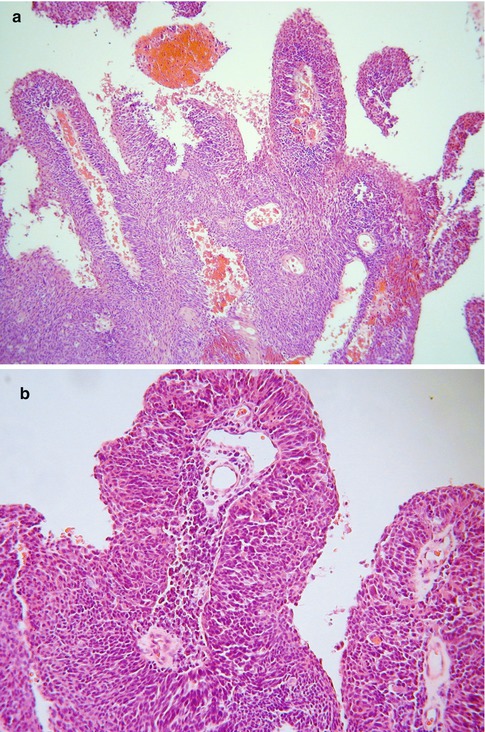

Grossly, cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma usually takes the form of a polypoid mass or multiple polyps which may be totally removed by polypectomy. Occasionally, there is an infiltrative growth pattern without a polypoid architecture but this is uncommon. The cut surface may be myxoid with areas of necrosis and some neoplasms have an overtly botryoid (grape-like) gross appearance.

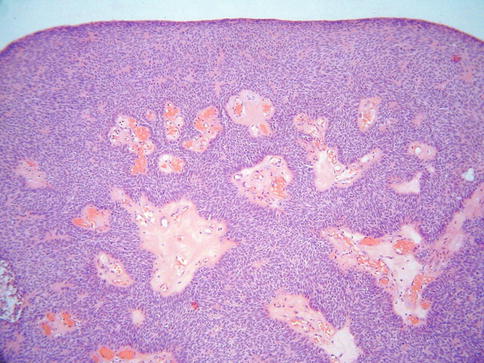

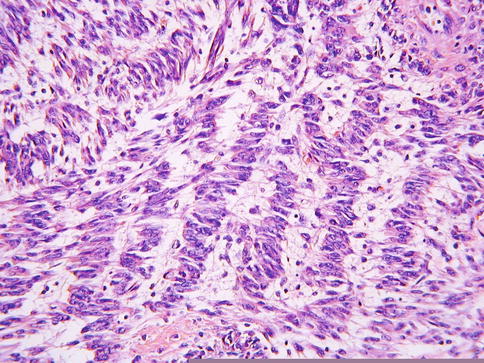

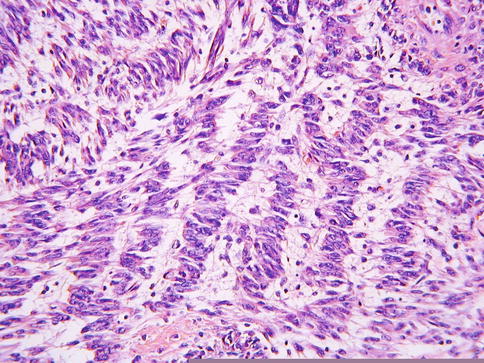

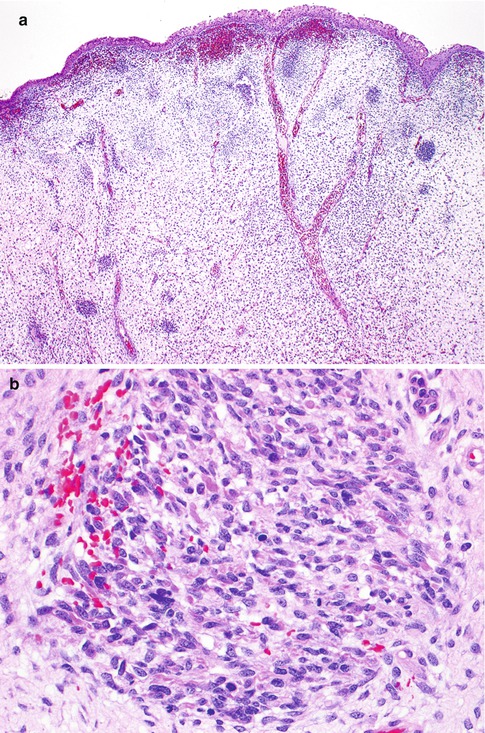

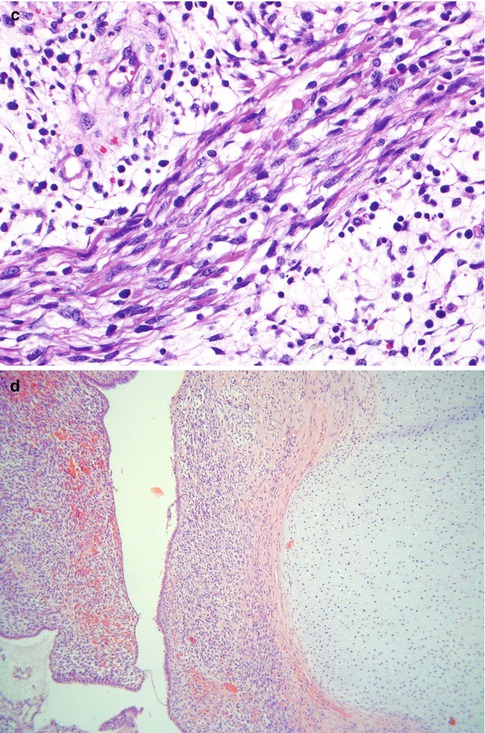

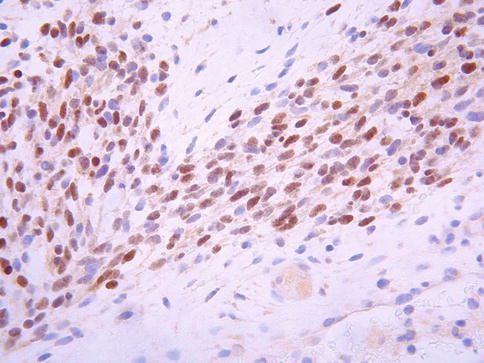

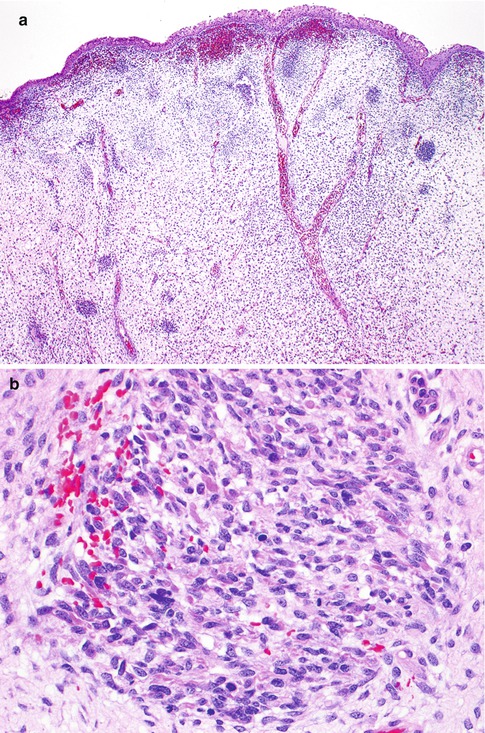

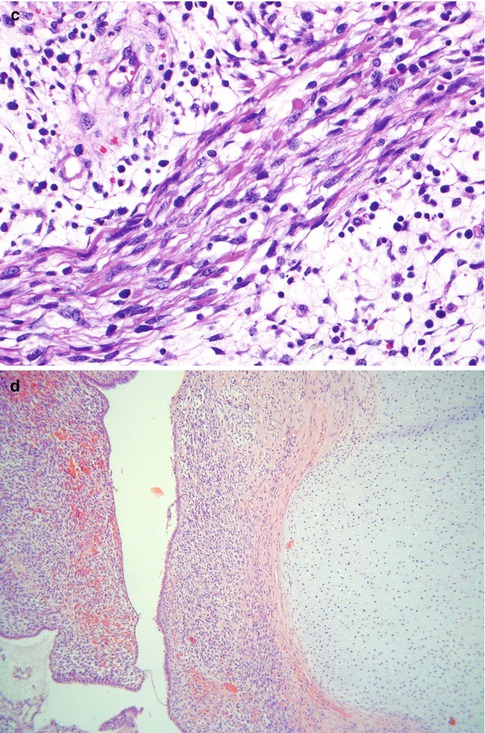

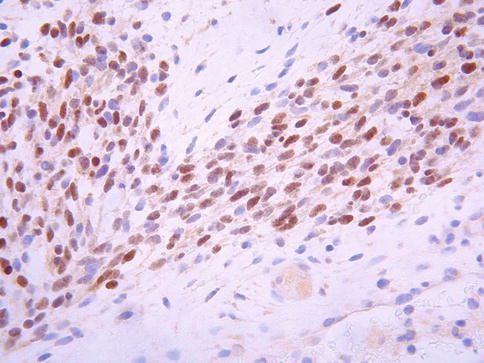

Histological examination characteristically shows a polypoid lesion covered by a variety of types of benign glandular Mullerian type epithelium, sometimes with focal squamous differentiation (Fig. 5.9a). Glands may also be present quite deep within the core of the neoplasm. The features of malignancy may be subtle in that, in large part, the stroma can be hypocellular and myxoid or oedematous. However, tightly packed hypercellular foci are also present which sometimes coalesce to form large cellular aggregates. There is usually mitotic and apoptotic activity within the cellular foci (Fig. 5.9b). Characteristically there is increased cellularity around the glandular elements, resulting in a cambium layer and here mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies are usually apparent. Most of the stromal cells have small hyperchromatic nuclei with scant cytoplasm and delicate cytoplasmic processes but cells with larger nuclei and an almost epithelioid appearance may be present. Cells with more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and cytoplasmic cross striations may also be identified (Fig. 5.9c) but these are typically difficult to find, are not present in all cases and are not necessary for the diagnosis. Islands of hyaline or cellular, but benign, cartilage are a common feature being found in approximately 50 % of these neoplasms (Fig. 5.9d), a much higher incidence than in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma arising at other sites [21–25]. In occasional cases, there are foci resembling alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma or collections of pleomorphic cells with multilobated nuclei are present; the clinical significance of these features is uncertain [24, 27]. Hyaline globules may be present in association with the pleomorphic cells. There are commonly areas of haemorrhage with extravasated erythrocytes or necrosis. Positive nuclear staining with the skeletal muscle markers myogenin and myoD1 assists in diagnosis but typically only a minor proportion of the nuclei are immunoreactive (Fig. 5.10). Desmin is usually positive but it should be noted that normal cervical stroma is also desmin positive. Hormone receptors (ER and PR) are generally negative.

Fig. 5.9

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of cervix with low power polypoid architecture. The lesion is covered by squamous epithelium and the underlying stroma is somewhat oedematous with cellular foci (a). Cellular aggregates exhibiting mitotic activity (b). Collections of cells with more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm are present in some cases (c). Islands of cellular cartilage are present in some cases (d)

Fig. 5.10

Cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma exhibiting nuclear staining with myogenin

Given the polypoid nature of the lesion and the presence of a cambium layer, one of the main differential diagnoses is adenosarcoma with heterologous stromal elements, especially in those cases where glands are present deep within the core of the neoplasm. An absence of the typical phyllodes-like (club-like or leaf-like) architecture of adenosarcoma is helpful, as is the usual relative paucity of glands deep within the stroma. Adenosarcomas usually occur in an older age group. However, in some cases the distinction between embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and adenosarcoma may be arbitrary and it is possible that some cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas represent a form of adenosarcoma with heterologous stromal elements and stromal overgrowth. Given the hypocellular background, an unusual benign endocervical or endometrial polyp or endometriosis may also be considered in the differential diagnosis but these are usually easily excluded given the morphological features described above.

Most cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas are treated by a combination of surgery (which may be radical or comprise local conservative excision) and chemotherapy and the overall prognosis is good with an 80 % overall survival [21, 24, 25]. The main adverse prognostic feature is deep invasion of the cervical stroma but this is uncommon.

Myofibroblastoma of the Lower Female Genital Tract

Myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital (also referred to as superficial cervicovaginal myofibroblastoma) is an uncommon mesenchymal neoplasm most commonly occurring in the vagina but also arising more uncommonly in the cervix [28–30].

This lesion was first described by Laskin et al. who reported a distinctive mesenchymal tumour arising in the superficial lamina propria of the cervix and vagina [28]. The term superficial cervicovaginal myofibroblastoma was proposed to encompass the superficial location in the cervix or vagina and presumed myofibroblastic differentiation. A subsequent series of cases involved the vagina and the vulva and the term superficial myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract was proposed since some neoplasms have a vulval location [29].

These neoplasms occur in premenopausal or postmenopausal women and usually present as polypoid lesions. Some patients have been taking tamoxifen, raising the possibility of an association with this medication [28–30]. Based on the morphology and follow up, superficial myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract is a benign lesion, although there is uncommonly local recurrence following excision [28–30]. Metastasis or malignant transformation has not been reported.

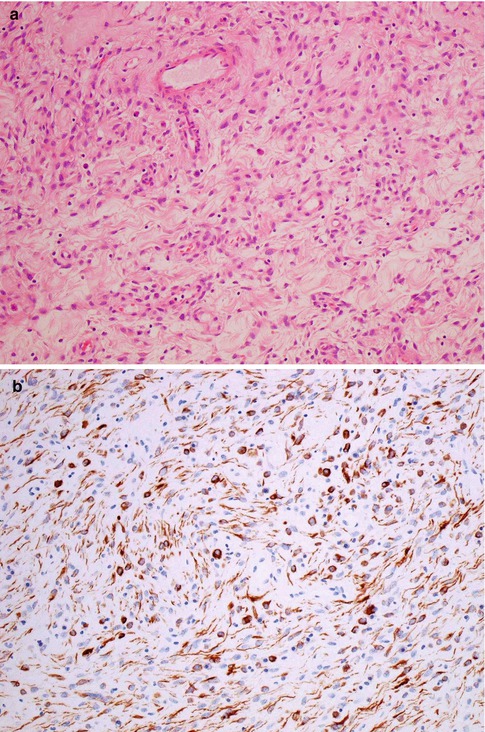

Grossly these are well circumscribed and are often, but not always, polypoid in appearance. Histological examination shows a well-circumscribed but unencapsulated lesion covered by unremarkable squamous or glandular epithelium. Deep to the surface epithelium, there is usually an uninvolved Grenz zone, although sometimes the lesion extends up to the epithelial-stromal junction. There are typically areas of varying cellularity, the constituent cells having bland ovoid, spindled or stellate nuclei, sometimes with a somewhat wavy appearance, embedded in a finely collagenous stroma, sometimes with thicker collagen bundles (Fig. 5.11a). Multiple architectural patterns, including lace-like, sieve-like and fascicular, which result in a heterogeneous appearance, are a characteristic feature, as are myxoid or oedematous foci. Few or no mitoses are present.

Fig. 5.11

Superficial myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract with bland spindle shaped cells in an oedematous stroma (a). There is diffuse staining with desmin which highlights dendritic cell processes (b)

The cells are positive with vimentin and usually with desmin [28–30]. CD34 and smooth muscle actin (SMA) are positive in some cases and most are ER and PR positive. S100, EMA, h-caldesmon, HMGA2 and cytokeratins are negative. Desmin staining typically highlights the ramifying dendritic processes of many of the tumour cells (Fig. 5.11b) [28–30]. The immunophenotype is nonspecific and identical to that of many of the other site specific mesenchymal lesions which involve the lower female genital tract, especially the vulva and vagina.

The main differential diagnosis in the cervix is likely to be an unusual endocervical polyp and focally the stroma of endocervical polyps may resemble myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract. However, mucinous glands are usually present throughout endocervical polyps while more than an occasional entrapped gland is unusual in myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract. A fibroepithelial polyp may also enter into the differential diagnosis. The Grenz zone which is typical of superficial myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract is not a feature of fibroepithelial polyp and the former is characterised by a more heterogenous appearance with a variety of architectural patterns. Negative staining with S100 helps to exclude a neural lesion since some of the morphological features, such as the presence of wavy nuclei, may raise this possibility.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree