(1)

Department of Pathology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Keywords

Maxillofacial BoneNeoplasms11.1 Introduction

The maxillofacial skeleton harbours lesions that cannot be put among one of the categories that have been discussed in the previous chapters as they are not derived form the tooth forming tissues, neither are they forming bone of cartilage. However, as they either play a role in the differential diagnosis of the bone diseases discussed in the other Chapters or have the bones of the head and neck as unique location, they have to be included in a text devoted to maxillofacial bone pathology. The lesions discussed in this Chapter are: desmoplastic fibroma, non-ossifying fibroma, melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy, myoepithelioma of bone, chordoma, and epitheloid hemangioendothelioma.

11.2 Desmoplastic Fibroma

Desmoplastic fibroma is a rare bone tumor that may involve the jaws, predominantly the mandible in about one fifth of cases. Asymptomatic swelling of the jaw is the most often encountered sign at initial presentation [1]. Radiographs show a radiolucent and expansile lesion, an appearance shown by a lot of other intraosseous lesions and hence not specific.

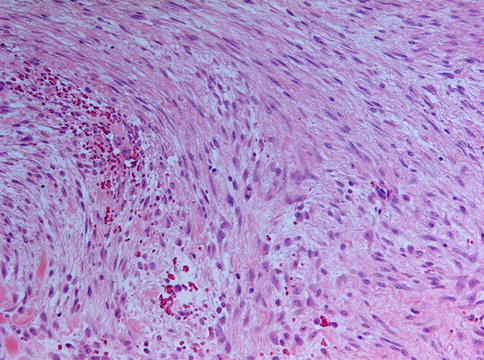

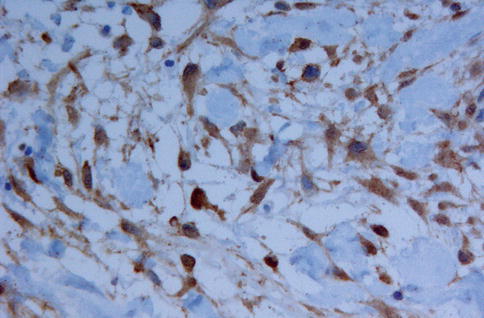

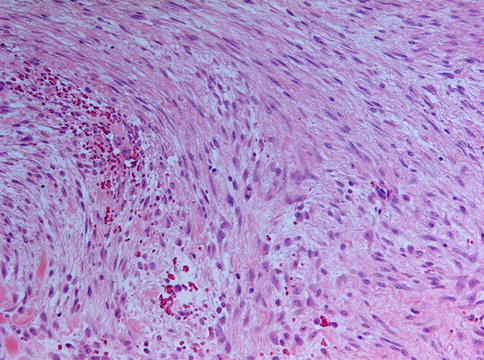

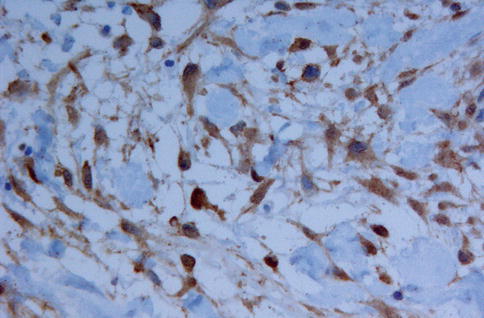

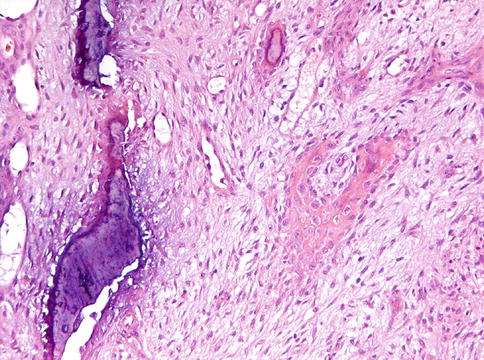

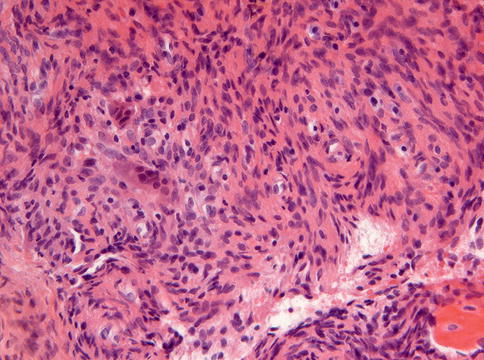

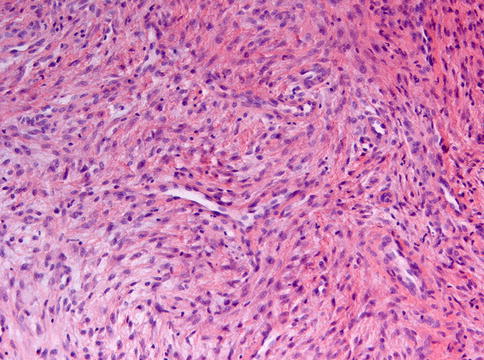

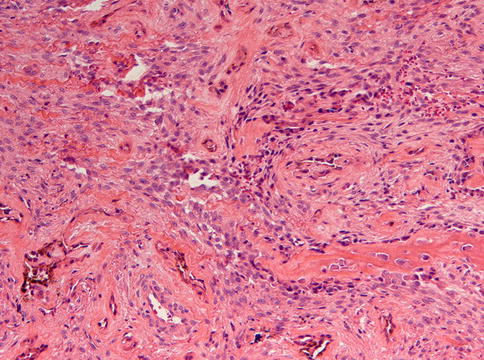

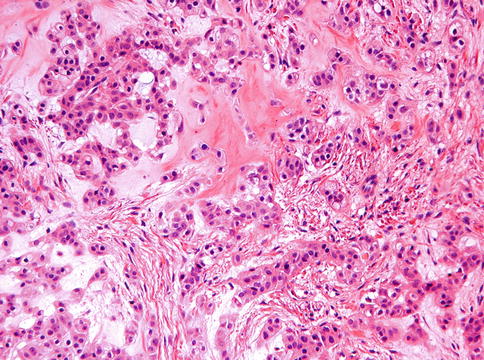

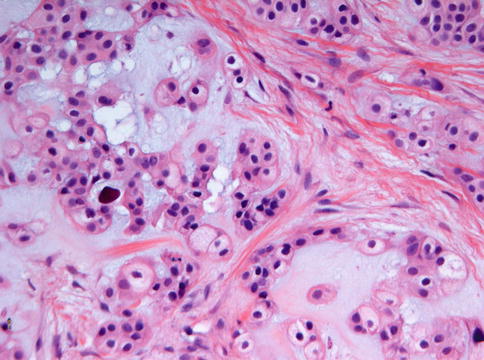

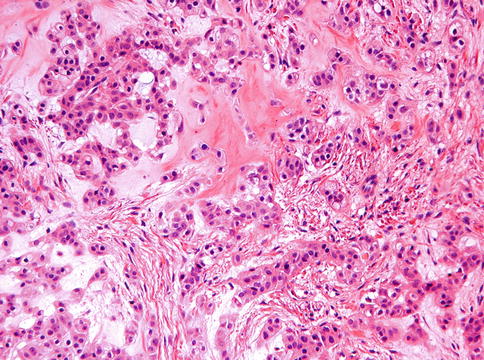

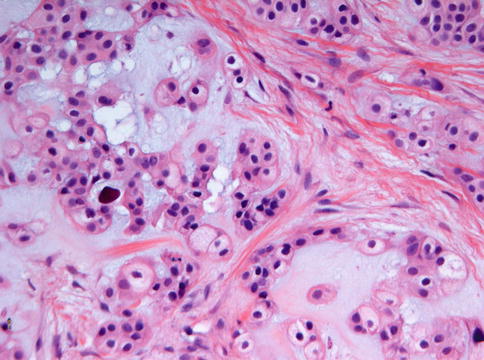

Histology shows a proliferation of uniform spindle cells in a collagenous background with varying degrees of myxoid changes. The cells are arranged in a parallel fashion mixed with whorling bundles (Fig. 11.1). They usually show focal reactivity for smooth muscle actin while being nonreactive for S-100 protein and muscle-specific actin. Nuclear expression of beta-catenin is also occasionally observed (Fig. 11.2) but whether this is due to the same genetic changes as in desmoid type fibromatosis in which this nuclear expression of beta-catenin also is present is controversial [2, 3].

Fig. 11.1

Desmoplastic fibroma is composed of elongated cells with spindle-shaped nuclei lying in a collagenous background that may show some myxoid changes. A few mitotic figures may be encountered

Fig. 11.2

Nuclear expression of beta-catenin may be helpful in distinguishing desmoplastic fibroma from other spindle cell bone lesions

Low-grade fibrosarcoma and odontogenic fibroma are the most important lesions to differentiate from desmoplastic fibroma. In fibrosarcoma, the cells often are arranged in the so called “herring bone” pattern and moreover the nuclei are not as monotonous as in desmoplastic fibroma. In odontogenic fibroma, the cells are not arranged in bundles but more randomly distributed in a background that may vary from densely fibrous to immature myxoid and may contain odontogenic epithelium as well as calcifications (see Chap. 4 for more details on odontogenic fibroma). Moreover, neither fibrosarcoma nor odontogenic fibroma show expression of smooth muscle actin.

Nodular fasciitis also may enter the differential diagnosis if located adjacent to the bone and thereby involving the periosteum, a condition known as cranial fasciitis and in the past reported under the designation periosteal fasciitis for cases involving the mandible [4]. This may lead to remodeling of adjacent cortical bone and development of metaplastic ossification that not only may mimic peripherally located osteosarcoma as already discussed in Chap. 9 but also could be mistaken for intraosseous desmoplastic fibroma breaking through the cortex and involving the adjacent soft tissues (Figs. 11.3, 11.4, 11.5 and 11.6). However, nodular fasciitis lacks nuclear expression of beta-catenin [5] and furthermore, genetic analysis may be helpful in solving this differential diagnostic problem because USP6 rearrangement has been found in all investigated nodular/cranial fasciitis cases, suggesting that USP6–FISH represents a useful diagnostic adjunct in difficult cases [6]. Recognizing nodular fasciitis is important because treatment for this condition can be more limited than for desmoplastic fibroma and, of course, than for osteosarcoma.

Fig. 11.3

Radiograph showing cranial fasciitis close to the lower border of the mandible resulting in bone erosion. For this condition, the designation periosteal fasciitis is also employed. Bone erosion should not be mistaken for real invasion leading to an erroneous diagnosis of malignancy

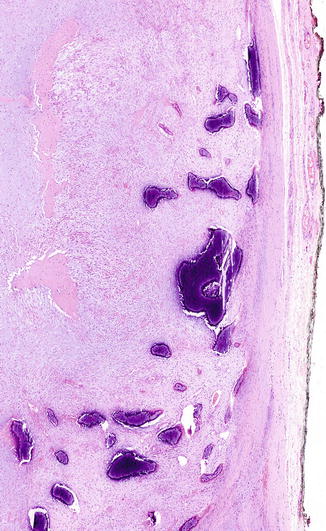

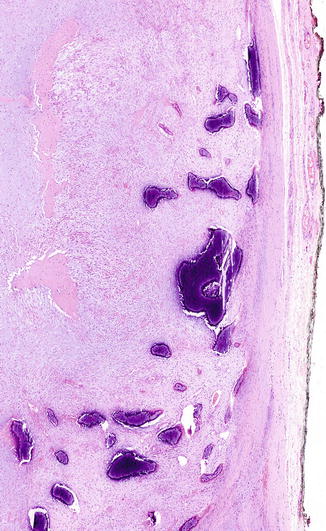

Fig. 11.4

Low power view of cranial fasciitis with metaplastic ossification, both within the lesion as well as peripherally located

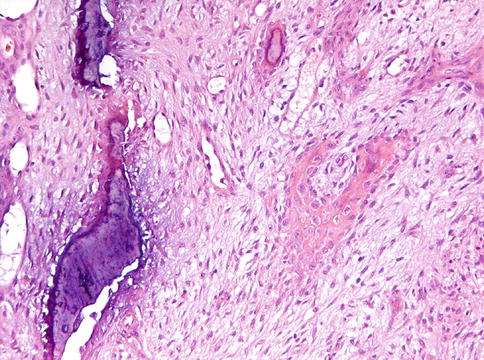

Fig. 11.5

Detail from Fig. 11.4. At intermediate magnification, the difference between the compact cortical bone (left side) and the lesional metaplastic bone (right side) is clearly visible

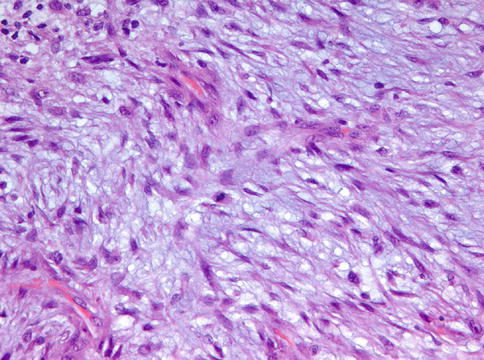

Fig. 11.6

High power detail from Fig. 11.4 to show the cytonuclear details of cranial fasciitis. Some mitotic activity can be present

Finally, it has to be emphasized that desmoplastic fibroma arising within bone cannot always be separated reliably from a desmoid type fibromatosis that secondarily involves bone. In these cases, clinical and radiographic features are critical for an appropriate categorization.

Treatment planning should acknowledge the lesion’s lack of encapsulation. Patients treated by curettage showed more often postsurgical recurrence than those treated with either resection or excision [7].

11.3 Non-ossifying Fibroma

Non-ossifying fibroma is a benign lesion most commonly seen in the metaphyses long bones in children. In the head and neck region, the lesion is rare with only a low number of cases reported until now; all of them occurring in the mandible, both in ascending ramus as well as body. Other terms in use for this lesion are histiocytic fibrous defect, metaphyseal fibrous defect, fibrous cortical defect, fibrous xanthoma and histiocytic xanthogranuloma [8].

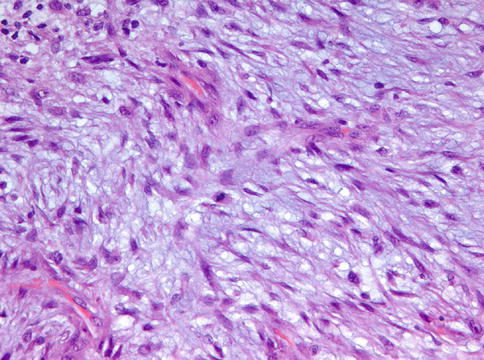

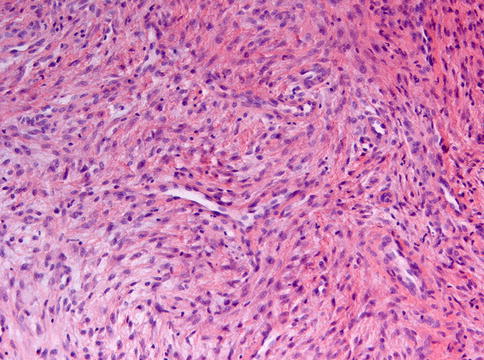

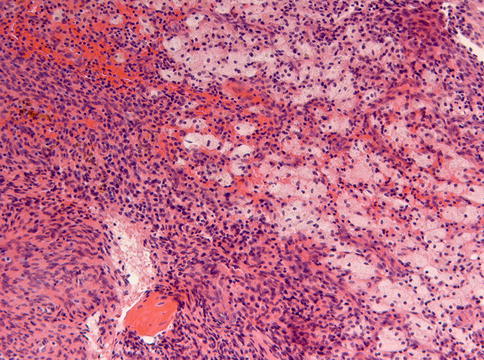

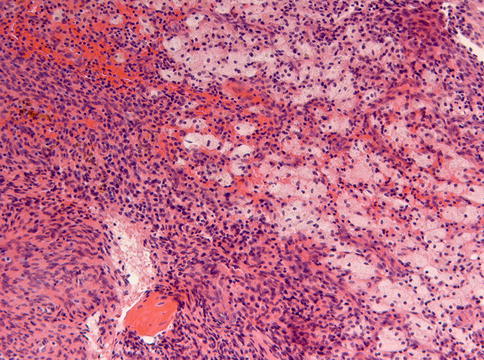

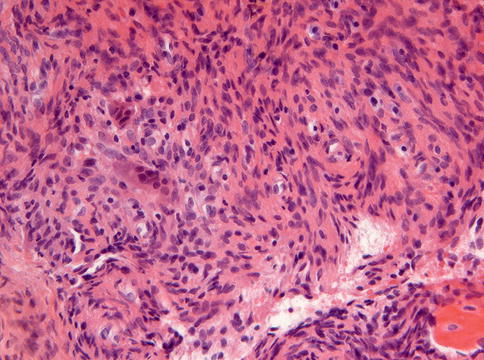

Histologically, non-ossifying fibroma consists of spindle-shaped fibroblasts lying in a storiform pattern and admixed with variable numbers of multinucleated giant cells and foam cells and depositions of hemosiderin pigment (Figs. 11.7, 11.8 and 11.9). Occasionally, foci of osseous metaplasia can be seen.

Fig. 11.7

Non-ossifying fibroma showing spindle cells lying in bundles

Fig. 11.8

Focally in non-ossifying fibroma, an admixture of spindle cells and foam cells is shown. Also some depositions of hemosiderin pigment form part of the picture

Fig. 11.9

Small multinucleated giant cells also form part of the histomorphology of non-ossifying fibroma

The main differential diagnoses is central giant cell granuloma but this lesion shows much higher numbers of osteoclastic giant cells than are usually observed in non-ossifying fibroma [9].

The prognosis of non-ossifying fibroma is excellent, lesions responding favorably to curettage and sometimes even showing spontaneous resolution [8].

11.4 Melanotic Neuroectodermal Tumor of Infancy

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy in the past also was known as retinal anlage tumor or melanotic progonoma due to a presumed derivation from cells destined to form the retina. Currently, the idea is that this tumor originates from the cells that migrate from the cranial neural crest and that play a major role in the development of jaws and teeth [10, 11]. Most of them occur before the age of 1 year. The anterior maxilla is the privileged site but other sites in the head and neck area also may be involved [12–14] and the clinical appearance may be alarming as the lesion may manifests itself as a rapidly growing blue tissue mass (Figs. 11.10 and 11.11).

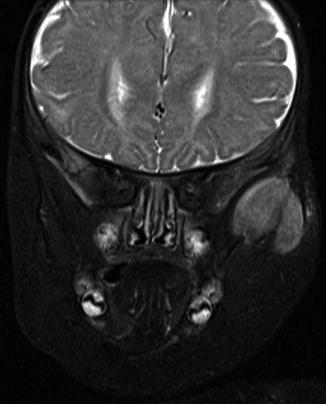

Fig. 11.10

MRI of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy at the anterior maxilla which is the most typical location for this tumor

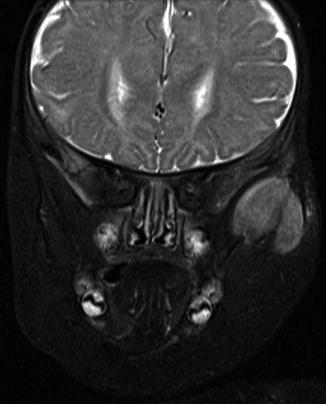

Fig. 11.11

MRI of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor at a less classical site, the zygomatic arch

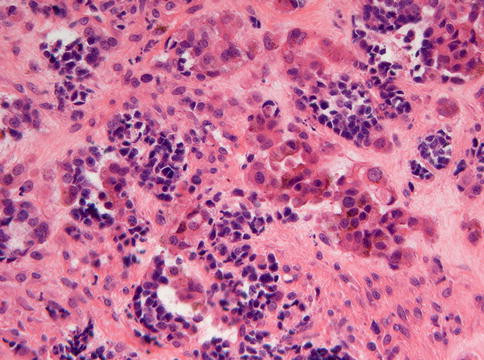

Histologically, the tumor shows dense fibrous stroma with nests composed of two different cell types: centrally placed small dark cells without any discernable cytoplasm and peripherally located larger cells with vesicular nuclei and ample cytoplasm with melanin pigment (Figs. 11.12 and 11.13) [13, 15, 16]. Maturation of the small cells to ganglion cells has been reported [17]. Although the cells may be atypical, mitotic figures are rare [15]. Sometimes, a transition of the large cells to osteoblasts forming tiny bony trabeculae can be observed [18]. The lesion is not encapsulated.

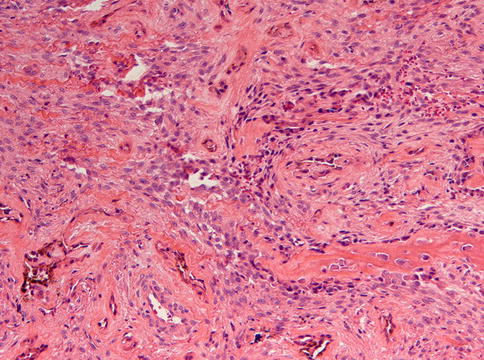

Fig. 11.12

Low power view of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy to illustrate the distribution of the epithelial nests in a stromal background that varies in cellularity and in which bone formation may occur

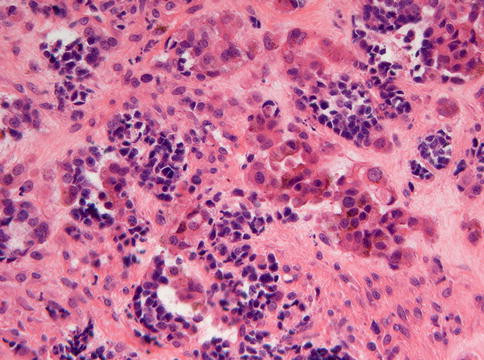

Fig. 11.13

Higher magnification of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor to show both the large cells containing granular melanin pigment as well as the smaller cells similar to neuroblasts

The neuroectodermal nature of the cells is reflected in their immunoprofile. The large cells are positive for a wide variety of cytokeratins, neuron specific enolase, S100, HMB45, and chromogranin. The small cells showed positivity for CD56, neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, and chromogranin [15]. This pattern can be summarized as evidence for neural, melanocytic, and epithelial differentiation. In addition, the large cells have been shown to be positive for vimentin [18].

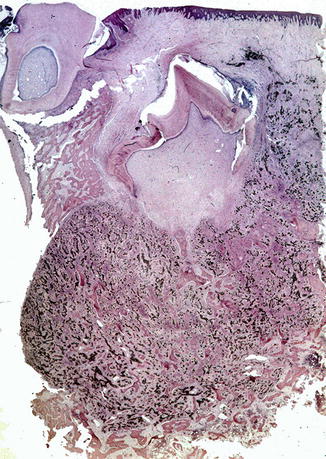

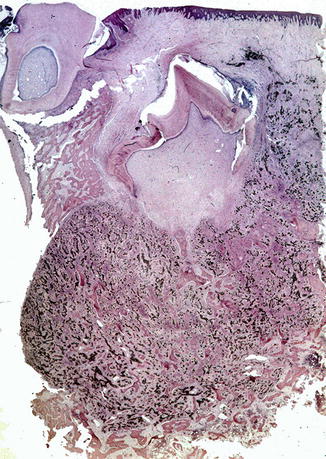

The highly specific age distribution and histomorphology leave no room for differential diagnostic considerations. However, quite often, immature odontogenic tissues form part of the material excised or biopsied, due to the early age of occurrence and the close association of the tumor with tooth germs (Fig. 11.14). This should not be mistaken as evidence for some type of odontogenic tumor.

Fig. 11.14

Low power view to show the intimate association of melanotic neuroectodermal tumor with the teeth

11.5 Myoepithelial Tumors

Myoepithelial tumors of bone are lesions being morphologically and immunophenotypically similar to their counterparts in salivary glands and soft tissue [19, 20]. Although very rare are they nevertheless included in this text because the differential diagnostic problems they cause when occurring within the jaws (Fig. 11.15).

Fig. 11.15

Panoramic radiograph of a mandibular myoepithelioma which initially on basis of this picture was considered to be an odontogenic tumor or cyst. The lesion recurred 4 years after conservative removal

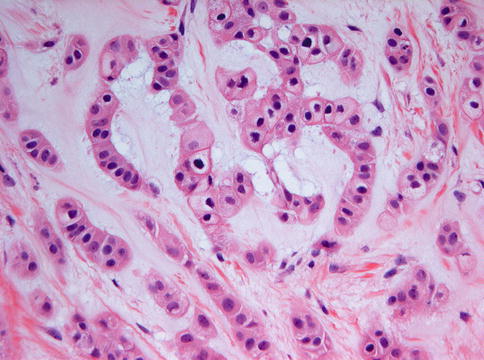

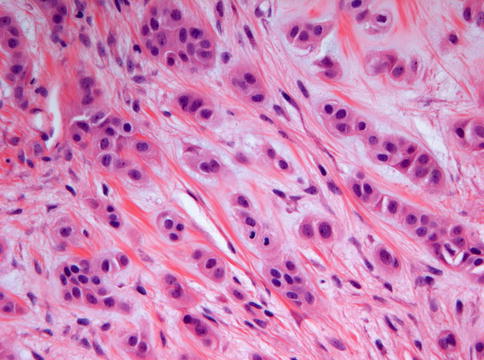

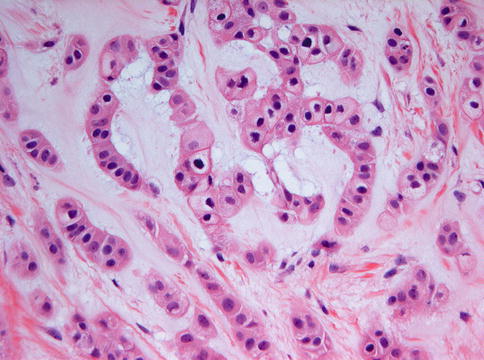

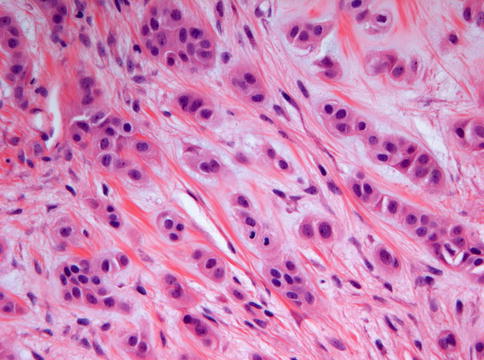

Histologically, these tumors show strands of epithelial cells with a cytoplasm that varies from eosinophilic to clear that lie in a mucoid background; occasionally some chondroid differentiation may dominate the picture (Figs. 11.16, 11.17, 11.18 and 11.19). When there is no nuclear atypia, tumors are best classified as benign; in case of moderate to severe nuclear atypia with vesicular or coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli, cases may behave in a malignant fashion [21, 22].

Fig. 11.16

Photomicrograph of myoepithelioma showing epithelial nests and strands in a mucoid background. Cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm and may show some vacuolization

Fig. 11.17

Detail from myoepithelioma to illustrate the cytoplasmic vacuolization causing some resemblance to chordoma. Epithelial nests are surrounded by a mucoid matrix

Fig. 11.18

Detail from myoepithelioma to illustrate the resemblance of the eosinophilic cells to calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor which also may show strands of eosinophilic cells with an epithelial phenotype

Fig. 11.19

High power view of myoepithelioma to show the presence of an occasional mitotic figure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree