and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

15.6 Sialoblastoma

15.8 Oncocytic Carcinoma

15.10 Lymphoepithelial Carcinoma, Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Small Cell Carcinoma, and Large Cell Carcinoma

15.12 Hybrid Tumour

All neoplasms described in this chapter are rare, some exceedingly rare. Sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma is the most uncommon of all, and to date, only seven cases have been reported in the literature. Therefore, most general pathologists will very rarely, and, in many cases, will never, encounter some of these carcinomas in the routine work. Many may, possibly correctly so, regard this subclassification as hair splitting. Nevertheless, their existence as recognised distinct entities and thereby constituting possible differential diagnosis merits a rather detailed description. Further, being recognised as separate entities will also greatly facilitate to increase further clinicopathological and genetic knowledge about these tumours.

15.1 Cribriform Adenocarcinoma of the Tongue and Minor Salivary Glands

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue and minor salivary glands was originally described in 1999 by Michal and associates, and the name ‘cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue (CAT)’ was coined [5]. In the original series, all the tumours were located in the mucosa of the tongue. After the original publication, more cases of this distinctive, hitherto poorly recognised low-grade adenocarcinoma were collected and published [8]. This new series included several cases of identical tumour located outside the tongue, including the soft palate, retromolar buccal mucosa and palate, and hence the tumour was renamed as ‘cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue and other minor salivary glands (CATS)’. According to the current issue of the WHO Classification of Tumours of Head and Neck, CATS is a provisional entity without a clear statement as to whether it represents a genuine separate entity or is merely a variant of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) [4].

The original series published in 1999 by Michal and associates reported a distinctive type of adenocarcinoma occurring in the tongue characterised by synchronous metastases in lateral neck lymph nodes, but no distant spread [5]. Of the so far 31 published cases in the literature, 21 tumours were located in the tongue (usually the base), 3 in the soft palate, 2 in the retromolar buccal mucosa, 3 in the lingual tonsils, 1 in the upper lip and 1 in the floor of the mouth. One tumour located in the tongue was described to have a pedunculated configuration [7]. The sex was known in 27 patients: the tumours occurred in 15 women and 12 men. The age of the patients ranged from 21 to 85 (mean 56.8 years) [1–3, 5, 7, 8]. Most patients (19 of 31) presented with metastases in the cervical lymph nodes, mostly at approximately the same time as the diagnosis of the primary (bilateral in three cases) and one after an interval of 8 years. The primary sites in the lymph node positive cases were in most cases the posterior tongue and retromolar mucosa. However, cervical lymph node metastasis appeared also in extralingual cases including primary of tonsils (two cases) and the palate (one case) [6]. The tumour size ranged from 3 to 8 cm in greatest dimensions. Grossly, all the tumours were covered by intact mucosa devoid of ulcerations; they were unencapsulated, white-tan to grey in colour and hard in consistency with no areas of haemorrhage or necrosis.

15.1.1 Histopathology

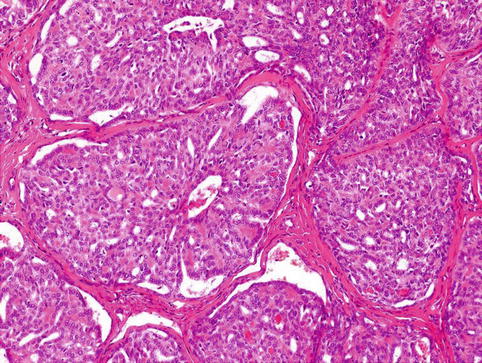

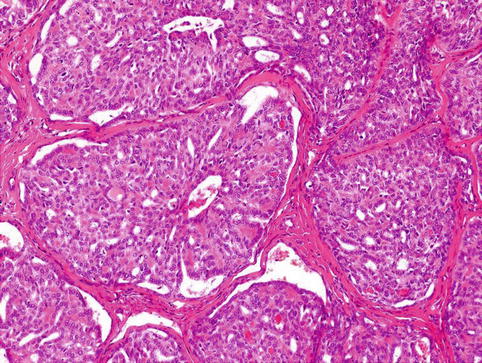

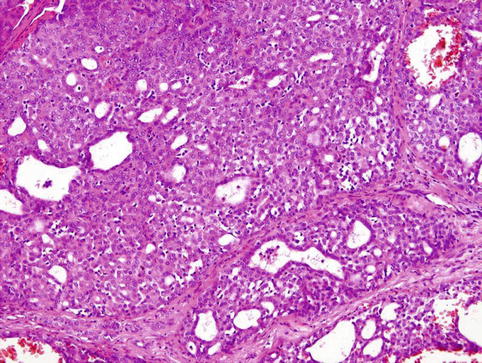

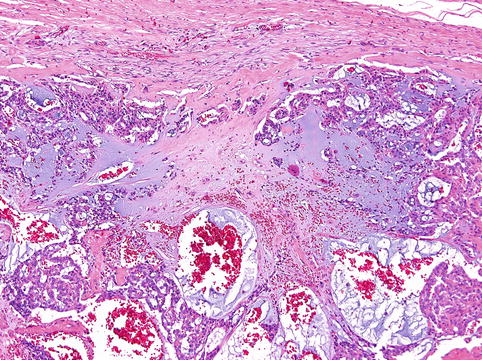

Histologically, the tumours have invasive margins, in most cases with infiltration of the muscular layer of the tongue and/or adjacent tissues. Lymphovascular invasion is observed in about half of cases. There are often deposits of hemosiderin in focally hyalinised interstitial stroma close to the invasive border of the lesions. The tumours are composed predominantly of cribriform and solid structures in variable proportions. In most instances the tumour architecture consists mainly of a solid mass, often divided by fibrous septa into irregularly shaped and sized nodules composed of solid, cribriform and microcystic structures (Fig. 15.1). In the solid areas, the tumour nests are detached from the surrounding fibrous stroma by (presumably artefactual) clefts, giving a glomeruloid appearance. The peripheral layer of such solid tumour nests often displays hyperchromatic nuclei in a palisaded pattern (Fig. 15.2). Typically, the tumours also include intermingled tubular, solid and cribriform growth patterns (Fig. 15.3). The tubules are approximately all of the same size and they consist of one cell layer [6]. A characteristic feature, not described in the original series [5], is a presence of myxoid mucin-rich stromal septa with rare spindle-shaped myofibroblastic cells (Fig. 15.4) [6].

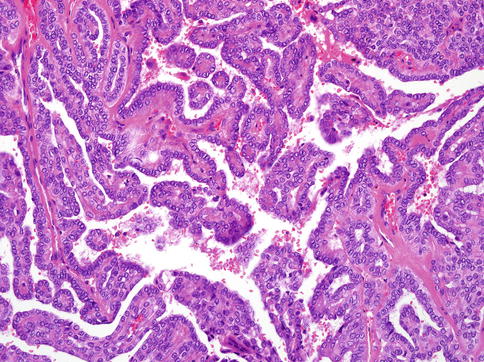

Fig. 15.1

Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue (CATS) is an infiltrating tumour composed of solid and microcystic structures covered by intact mucosa

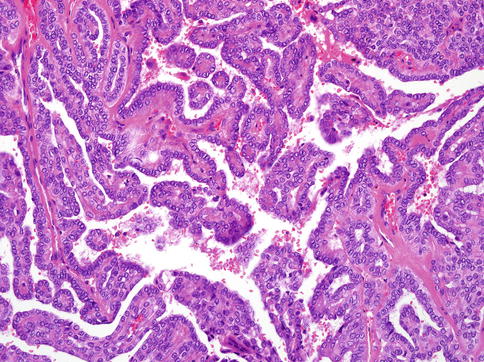

Fig. 15.2

Tumour nests are detached from the surrounding fibrous stroma by artificial clefts. The peripheral layer of such solid tumour nests often displays hyperchromatic nuclei in palisaded pattern

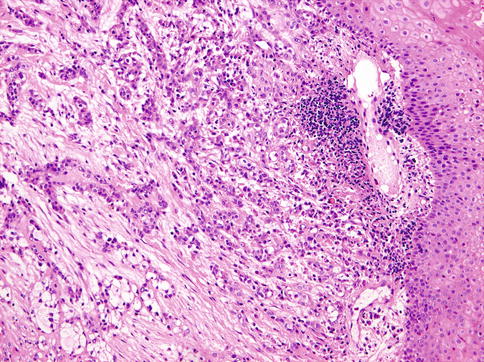

Fig. 15.3

The other parts of CATS are composed of intermingled tubular, solid and cribriform growth patterns

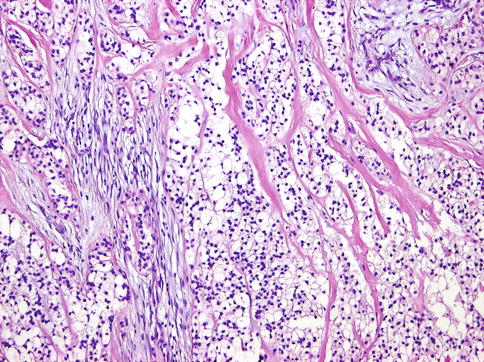

Fig. 15.4

Presence of myxoid mucin-rich stromal septa with rare spindle-shaped myofibroblastic cells

The most prominent feature of the tumours, however, is the appearance of the nuclei. These overlap one another and are pale, optically clear and vesicular with a ground glass appearance, so that the tumours cytologically strongly resemble papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland (Fig. 15.5). Cellular atypia is mild, and mitotic figures are in most cases rare. The cytoplasm is clear to eosinophilic and often abundant. Cytologically, all the tumours are composed of one cell type. The overall morphology of the tumour, particularly with focal papillary growth and with overlapping clear ‘Orphan Annie eyelike nuclei’, is remarkably similar to primary or metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma. The cervical lymph node metastases have identical appearance to the primary tumours.

Fig. 15.5

The nuclei of CATS often overlapped one another. They are pale, optically clear and vesicular with a ground glass appearance, so that the tumours cytologically strongly resemble papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland

15.1.2 Immunohistochemistry and Genetics

CATS is characterised by co-expression of cytokeratins (AE1-3, CAM5.2, CK7, CK8, CK18), S-100 protein and vimentin. Basal and myoepithelial cell markers, such as p63, calponin, CK14, smooth muscle actin and CK5/6, are positive in all tumours with variable proportions up to 60 %. Often the palisaded cells surrounding the glomeruloid structures are positive for these markers. Proliferative activity is usually low. EMA, EGFR and HER2/neu are negative in all cases. More importantly all the tumours are completely devoid of any staining for TTF1 and thyroglobulin, though variable expression of galectin-3, CK19 and HME-1 can be detected in some cases [3].

No somatic mutations of BRAF, K-RAS, H-RAS, N-RAS, C-kit and PDGFRa genes were found in any of the analysable cases in two papers [3, 8]. However, in RET proto-oncogene, heterozygous polymorphism Gly691Ser in exon 11 (one case), heterozygous polymorphism p.Leu769Leu in exon 13 (one case), heterozygous polymorphism Ser904Ser in exon 15 (one case) and intronic variant p.IVS14-24G/A of exon 14 (two cases) were found in one study [3].

15.1.3 Differential Diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis of CATS is PLGA. This neoplasm typically has a wide range of architectural appearances, including tubule and fascicle formation, as well as solid, cribriform and sometimes small papillary structures. A particularly characteristic feature of PLGA is the occurrence of streaming columns of single file or narrow trabeculae of cells forming concentric whorls, thereby creating a target-like appearance [4]; perineural invasion is often seen, but does not indicate more aggressive behaviour. At the cellular level, PLGA quite often contains clear cells and less frequently mucous cells. Perhaps most importantly, the most striking feature of CATS is the great nuclear similarity to papillary carcinoma of the thyroid, and this is not seen to any great extent in PLGA. The most significant differential diagnosis of CATS is from metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid, particularly if nodal disease is the first presentation. CATS is always thyroglobulin and TTF1 negative and devoid of colloid. However, one must be alert to the fact that both CATS and papillary thyroid carcinoma may show variable expression of galectin-3, CK19 and HBME-1 [3]. In contrast to thyroid cancer, all cases of CATS stain strongly for S-100 protein, and focal myoepithelial differentiation with calponin and actin positivity is common.

15.1.4 Treatment and Prognosis

The tumours were treated by surgical excision often accompanied by neck lymph node dissection. Of the 31 patients, 14 individuals additionally received radiotherapy and 1 adjuvant chemotherapy. All patients with available follow-up (range 2 months to 13 years; mean 4.3 years) were alive and without signs of metastases.

15.2 Hyalinising Clear Cell Carcinoma

Hyalinising clear cell carcinoma (HCCC) is believed to be first described by Milchgrub and associates in 1994 as a distinctive low-grade carcinoma of minor salivary glands composed of clear cell cords and nests divided by hyalinised stromal septa [23]. However, two cases of identical carcinoma of the minor salivary glands were presented 4 years earlier by Simspon and associates and considered as a distinct tumour of low malignant potential [26]. HCCC is currently classified as ‘clear cell adenocarcinoma’ in the AFIP fascicle [18] and as ‘clear cell carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS)’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) [17]. Antonescu and associates have recently identified a consistent EWSR1-ATF1 fusion in HCCC, which is not present in other salivary gland tumour containing clear cells [10]. Similar EWSR1 and ATF1 rearrangements have been also identified in clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC) providing molecular evidence of link between HCCC and CCOC [14].

15.2.1 Epidemiology and Clinical Features

The majority of HCCCs presumably originate from minor salivary glands in the oral cavity [23, 29]. The most common sites of origin are the palate and tongue base, followed by mobile tongue and other minor salivary locations. These include the lip, retromolar trigone, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth and gingiva. A minority can present as major salivary gland, nasopharyngeal or laryngeal tumours. A single lacrimal/orbital case has also been reported [10, 15, 23]. Primary nasal cavity and paranasal sinus locations have not been described so far. HCCC usually arises in patients in their 60s or older; however a broad age range is noted [10, 17, 18]. It is quoted as having equal sex distribution, although a slight female predominance was seen in one series [10].

The majority of HCCCs present as a mass inside the oral cavity. The tumours are generally submucosal, typically present as a swelling and may occasionally ulcerate [18]. Although some tumours may grow for many years, the majority of cases have a short history before a patient seeks medical attention. These lesions are often found at routine dental appointments, and so many are biopsied and examined first by oral surgeons or oral pathologists [29]. HCCC arising in the buccal mucosa, floor of mouth and gingiva may sometimes invade the bone, and the distinction between a mucosal and primary bone tumour may be difficult, especially since ‘central’ examples of HCCC have been described [12].

15.2.2 Histopathology

The tumour size ranges between 1.0 and 4.5 cm (mean 2.0–3.0 cm). Grossly, it has a white-tan cut surface. HCCCs may appear relatively circumscribed but lack encapsulation, and they have a tendency to have infiltration of the surrounding tissues despite this grossly circumscribed appearance.

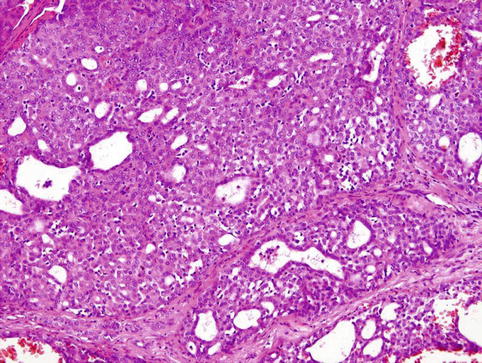

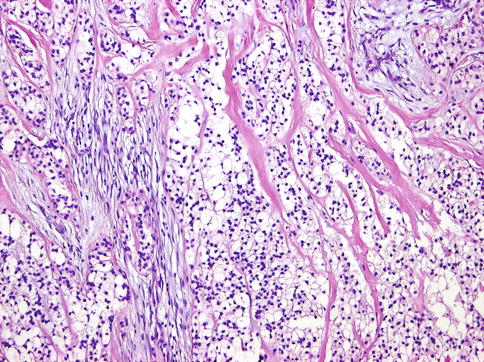

Histologically, the cells of HCCC are arranged in small nests, short and long cords, interconnecting thin trabecular structures and single cells. The neoplastic nests and lobules are surrounded by or admixed with a hyalinised basement membrane-like material (Fig. 15.6). The margins are infiltrative (Fig. 15.7). There is a wide range of appearance of HCCC tumour cells. The predominance of clear cells is seen in a minority of cases and the tumour cells in most cases have pale eosinophilic cytoplasm rather than clear cytoplasm, or they may have a mixture of both (Fig. 15.8). The presence of the hyalinised stroma in a cribriform arrangement may also mimic other more common salivary gland tumours, particularly in cases that are clear cell poor (Fig. 15.9). Tumour cells at the periphery of the mass have a greater tendency for nest formation and for wide infiltration without the stromal deposition or desmoplastic response. HCCC often connects to the surface mucosal epithelium either abruptly or as a pagetoid-like growth of single cells. It may be accompanied by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium (Fig. 15.10). This is seen in majority of oral cavity examples. Focal squamous differentiation of tumour nests can also be seen [29]. Perineural (PNI) and intraneural invasion are typical and occur in almost half of all cases [10]. The individual tumour cells are small and bland with minimal atypia (Fig. 15.11). Mitotic figures are rare and number <1 per 10 HPFs with only occasional cases showing up to 5 MFs per 10 HPFs. The nucleoli are small or inconspicuous. Necrosis is generally absent. Mucinous cells are sometimes readily apparent [10]. The clear cells show granular PAS positivity and diastase sensitivity, indicative of glycogen in the cytoplasm. These stains also highlight the hyalinised stroma. A Congo red is negative in all cases, despite the stroma appearing similar to amyloid [23]. HCCCs lack papillary growth, chondroid stroma or goblet cell-lined cystic spaces.

Fig. 15.6

The neoplastic nests and lobules are surrounded by or admixed with a hyalinised basement membrane-like material

Fig. 15.7

The margins of hyalinising clear cell carcinoma are often infiltrative

Fig. 15.8

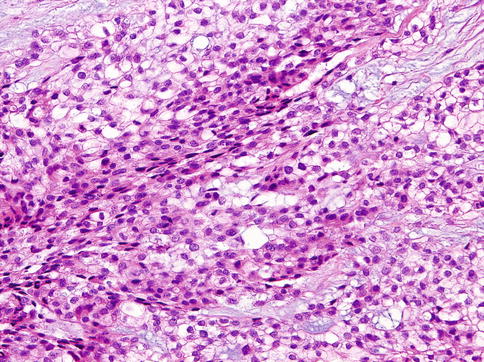

The tumour cells in most cases of HCCC have pale eosinophilic cytoplasm rather than clear cytoplasm, or they may have a mixture of both

Fig. 15.9

Presence of stroma in a cribriform arrangement of HCCC may mimic adenoid cystic carcinoma

Fig. 15.10

The infiltrative margins of the tumour may be accompanied by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium

Fig. 15.11

The individual tumour cells are small and bland with minimal atypia

15.2.3 Immunohistochemistry and Ultrastructural Findings

The vast majority of tumours are diffusely positive for pancytokeratin. Almost all cases are positive for 34βE12 and p63, suggestive of squamous differentiation (Fig. 15.12). Positivity for CK14 is also common. Many cases are focally or diffusely positive for EMA, CK7, CK19 and CAM5.2 as well. They are almost invariably negative for S-100, SMA, MSA, calponin and GFAP, ruling out myoepithelial differentiation. The hyalinised stroma is positive for collagen I and fibronectin but negative for collagen IV and laminin, arguing against this hyalinised stroma being basement membrane material. Collagen IV and laminin are only positive in a thin layer around tumour nests [19]. Ultrastructurally, the tumours have been shown to have tonofilaments, desmosomes and glycogen [17, 23]. These features are also suggestive of squamous differentiation in this tumour entity [16]. Additional findings on electron microscopy include some basal lamina reduplication [19].

Fig. 15.12

Almost all tumours cells are positive for p63 protein, suggestive of squamous differentiation

15.2.4 Genetics

Antonescu and associates have recently identified a consistent EWSR1-ATF1 fusion in HCCC, which is not present in other salivary gland tumour containing clear cells [10]. Similar EWSR1 and ATF1 rearrangements have been also identified in clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC) providing molecular evidence of link between HCCC and CCOC [14]. There are a distinct similarity between HCCC clear cell nests and stromal hyalinisation and similar features in some cases of soft tissue myoepithelial tumour (SMET), particularly those with a EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion transcript [9]. No rearrangement of PBX1, ZNF444 or POU5F1 was found however, suggesting that HCCC is not a salivary equivalent of SMET [10, 29].

No abnormalities in MAML2 gene in HCCC that carry a EWSR1 rearrangement by FISH were identified, which helps to distinguish HCCC with mucinous differentiation from mucoepidermoid carcinoma [10].

15.2.5 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes a number of neoplasms with clear cell change. Morphological and immunohistochemical overlap between entities makes differential diagnosis of clear cell tumours of the salivary glands confusing [28].

The tumours considered in the differential diagnosis of HCCC include clear cell variants of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), myoepithelial carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma, clear cell odontogenic carcinoma, clear cell calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, oncocytoma, myoepithelioma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Some of the above are both rare and lack cords and/or small nests of tumour cells (oncocytoma, acinic cell carcinoma, myoepithelioma) and so are not really a diagnostic dilemma. Since HCCC shows squamous features by immunohistochemistry, the most likely differential diagnosis will be with SCC and ‘mucin-depleted’ mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC). Contrary to the previous reports [23], the presence of mucin-containing cells on H&E or by mucicarmine, irrespective of numbers, does not exclude HCCC [10]. MEC is distinguished rather by a greater tendency for cyst formation lined by goblet-type mucinous cells, by solid growth of squamoid and intermediate cells and by a general lack of sclerosis/hyalinisation or small nests and thin cords of tumour. The latter feature is particularly unusual in MEC whilst mucin-lined cysts do not occur in HCCC. In difficult cases or small biopsies, fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) for MAML2 and/or EWSR1 can be used to resolve this dilemma [10]. SCC on the other hand can have sclerosis and thin cords of tumour cells. The principal difference with SCC is with the invariable atypia and mitotic activity that is lacking in HCCC. Even in the most ‘well-differentiated’ SCCs, there are always nuclear enlargement and usually ample mitotic figures. The presence of overlying mucosal dysplasia should also be a red flag against HCCC and in favour of SCC. Although HCCC does not have myoepithelial differentiation when stained with actins and calponin, myoepithelial tumours do enter the differential diagnosis. Firstly, they share basal/squamous immunohistochemical positivity for p63 and high molecular weight cytokeratins (HWMK). Secondly, the presence of myoepithelial marker positivity can be patchy or variable from case to case of true myoepithelial tumours. Finally, clear cell change is common in myoepithelial cells. Clear cell myoepithelial carcinoma is very rare with only few case reports and small series. Previous reports by Michal et al. showed strong expression with S-100 and actin in these tumours [22], which are lacking in HCCC [23]. In limited cases, there is also a lack of small thin cords in these tumours. The more common myoepithelial tumour that enters the differential diagnosis is epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (EMC), particularly when containing duct-poor myoepithelial overgrowth or conversely when an HCCC contains entrapped ducts. The latter occurs mostly in parotid HCCCs. In addition to lacking S-100, actin and calponin staining, which are usually present in EMC, HCCC does not form papillary structures, is more common in the oral cavity in contrast to EMC and generally shows smaller nuclei than EMC. HCCC also does not show spindling or oncocytic change which are often seen in EMC.

Tumours of odontogenic origin that can show clear cell change are many, and two in particular that overlap with HCCC are ‘clear cell odontogenic carcinoma’ (CCOC) and ‘clear cell calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumour’ (CEOT), also known as ‘Pindborg tumour’ [17]. These odontogenic neoplasms may be confused with either mucosal HCCC showing bone invasion, which is present in about 17 % of cases [10], or with primary ‘central’ HCCC [12]. Recently, Bilodeau et al. demonstrated EWSR1-ATF1 fusion in both clear cell odontogenic carcinoma (CCOC) and HCCC [14], having already previously concluded that there is morphological and immunohistochemical overlap [13], thus providing evidence that both tumour entities are identical and different from CEOT.

CEOT usually shows a squamoid eosinophilic neoplasm with intercellular bridges, calcification and a hyalinised background containing amyloid with some tumour cells containing amyloid as well [17]. Most tumours have solid areas, but areas with only small nests of tumour within a mostly amyloid-containing stroma may be seen. Occasional cases of CEOT show prominent clear cell change. Recently, Bilodeau et al. showed two cases of CEOT, initially called CCOC, which were very hypocellular and stromal predominant. Both of these tumours contained amyloid, as shown by Congo red, and lacked EWSR1 rearrangement [14], clearly separating it from HCCC. Clues to the diagnosis of CEOT over central HCCC are that they show greater nuclear irregularities and nuclear enlargement in a portion of the tumour cells, as opposed to the bland uniform nuclei of HCCC. In addition, the amyloid shows a more granular quality with the typical ‘cracking’ artefact that is lacking in the more sclerotic collagenous stroma that defines the hyalinisation of HCCC.

Finally, metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is always included on the differential diagnosis in every publication broaching the clear cell salivary differential diagnosis [11, 23]. However, renal cell carcinoma is more vascular and is generally either solid in growth or has a ‘crowded nested pattern’. The nuclei are larger and more atypical than seen in HCCC, and there is never squamous differentiation, and the dual stroma of HCCC is lacking. In addition, RCC never expresses p63 [21], which is almost always expressed in HCCC.

15.2.6 Treatment and Prognosis

The overall outcome is excellent. HCCC is a low-grade tumour with a propensity for locoregional recurrence [20, 28], and occasional lymph node [23] or distant metastases [28] have been noted. Only one documented mortality due to disease has been described [24], although an additional ‘palliative’ case has been reported [25]. Solar and associates reported a 25 % lymph node positivity rate in a review of reported cases [27]; however this is in sharp contrast to one large series which found no lymph node or distant metastases with reasonable follow-up (mean 48 months) [10]. In any event, the overall prognosis is still excellent in these latter cases. Treatment usually involves primary resection if the tumour arises in an amenable location. Tongue base tumours may have primary radiation due to morbidity of resection. Many cases have postoperative radiotherapy; however there is no standard of care for these tumours as they are rare and respond well in most instances irrespective of treatment.

15.3 Cystadenocarcinoma NOS

Cystadenocarcinoma is a rare malignant tumour of the salivary glands histologically characterised by invasive growth and multiple cystic structures lined by epithelium, frequently arranged in a papillary growth pattern. Cystadenocarcinoma represents malignant counterpart of cystadenoma [30].

15.3.1 Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Cystadenocarcinomas are rare neoplasms accounting for 0.5–2.0 % of malignant salivary gland tumours. Although the age range is broad (5–87 years), more than 70 % of patients are over 50 years of age. There is no sex predilection. Men and women are affected equally [32]. In the AFIP series about 60 % occur in major salivary glands; most of these were located in the parotid gland. Minor glands are affected in descending order in frequency in the palate, buccal mucosa, lips, floor of mouth and tongue [32].

The tumour presents as slowly growing asymptomatic mass, sometimes with mucosal ulceration.

15.3.2 Histopathology

Grossly, the tumours are cystic or multicystic, well-circumscribed unencapsulated lesions that usually range in size from 0.4 to 10 cm in greatest dimension with an average size of 2.4 and 2.2 cm in the major and minor salivary glands, respectively.

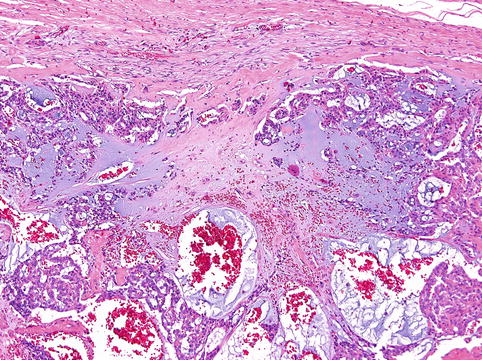

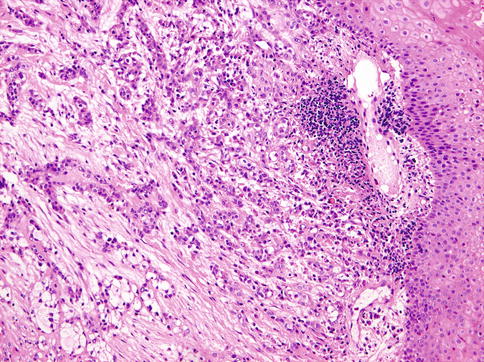

Histologically, the tumours are composed of predominant cystic spaces separated by connective tissue or closely related one to another with variable amount of intervening stroma (Fig. 15.13). The cysts vary in size and shape considerably; in some tumours the cystic spaces may be regularly arranged (Fig. 15.14). The lumens are mostly filled with homogenous, granular or bubbly secretions. The prominent papillary intracystic projections are often seen (Fig. 15.15). Focally, small nests of tumour cells invade the adjacent stroma (Fig. 15.16). The tumours are cytologically diverse. The cells lining the cystic spaces are most frequently simple cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells similar to intercalated duct epithelium (Fig. 15.17). In addition, there are areas containing cells with clear, mucus-producing, oncocytic or apocrine features (Fig. 15.18). Nuclear polymorphism and atypia are usually mild to moderate. Areas with solid growth pattern can be seen, and rare cases demonstrated comedo-like necrosis. Perineural invasion and psammoma bodies are occasionally noted [32]. Unusual case of micropapillary cystadenocarcinoma arising in mucinous cystadenoma of the parotid gland has been described (Fig. 15.19) [33].

Fig. 15.13

Cystadenocarcinoma is composed of predominant cystic spaces separated by connective tissue or closely related one to another with variable amount of intervening stroma

Fig. 15.14

The cysts vary in size and shape considerably; in some tumours the cystic spaces may be regularly arranged

Fig. 15.15

Prominent papillary intracystic projections are seen

Fig. 15.16

Small nests of tumour cells invade the adjacent stroma

Fig. 15.17

The cells lining the cystic spaces are most frequently simple cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells similar to intercalated duct epithelium

Fig. 15.18

Areas containing cells with clear, mucus-producing, oncocytic or apocrine features

Fig. 15.19

Micropapillary cystadenocarcinoma arising in mucinous cystadenoma of the parotid gland

Immunohistochemistry is rarely of any value in making diagnosis. The cells of cystadenocarcinoma co-express cytokeratins AE1-AE3, CK7, CK14 and p63 protein.

15.3.3 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis consists of cystadenoma; low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC); papillary-cystic variant of acinic cell carcinoma; polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA); low-grade variant of salivary duct carcinoma (SDC), called low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma in WHO 2005; and mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) [31, 34]. Cystadenomas can be separated from cystadenocarcinomas by their lack of stromal invasion and cellular atypias. Low-grade MEC may have cystopapillary structures but can be differentiated from cystadenocarcinomas by presence of mucus-producing cells intermingled with epidermoid cells lining the cysts and by presence of intermediate cells arranged in solid structures. The papillary-cystic variant of acinic cell carcinoma can cause considerable differential diagnostic confusion. Diagnosis of acinic cell carcinoma should be, however, based on the presence of microcystic and follicular growth patterns and serous acinar cells with PAS-positive zymogen granules in the cytoplasm. PLGA has variable architectural arrangement composed of uniform cells in nests, cords, ducts and cribriform patterns in addition to minor areas with papillary-cystic growth. Low-grade SDC is now considered a variant of cystadenocarcinoma displaying prominent cribriform structures, and therefore it is according to latest WHO called low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma (LGCC) [31]. LGCC is a rare, cystic proliferative carcinoma that resembles the spectrum of breast lesions from atypical ductal hyperplasia to low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ. Histologically, in contrast to conventional cystadenocarcinoma, LGCC is composed of solid, cribriform and anastomosing micropapillary intracystic structures. The cells of LGCC express cytokeratins CK7, CK8, CK18 and CK19 and S-100 protein. Cystadenocarcinomas tend to be invasive, whilst LGCC is usually surrounded by intact myoepithelial layer. There is, however, considerable overlap between LGCC and low-grade intraductal carcinoma described recently [35]. The concept of intraductal carcinoma has not gained a wide acceptance so far, and it is not included in the 2005 WHO classification. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a recently described new distinctive salivary gland tumour entity characterised by histomorphological and immunohistochemical resemblance to secretory carcinoma of the breast [34]. Microscopic features of MASC closely mimic intercalated duct cell predominant acinic cell carcinoma and low-grade cystadenocarcinoma. Histologically, MASC shows a lobulated growth pattern and is composed of microcystic, tubular and solid structures with abundant eosinophilic homogeneous or bubbly secretory material. The secretory material stains positive for periodic acid-Schiff with and without diastase and for alcian blue. However, in contrast to acinic cell carcinoma, the cells of MASC are devoid of PAS-positive secretory zymogen granules. MASC of the salivary glands, similarly as secretory carcinoma of the breast, harbours a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25) which leads to a fusion gene between the ETV6 gene on chromosome 12 and the NTRK3 gene on chromosome 15.

15.3.4 Treatment and Prognosis

The prognosis of cystadenocarcinomas varies depending on the grade and stage of the tumour. The majority of cystadenocarcinomas are low-grade or intermediate-grade neoplasms. Treatment should be relevant to the grade and stage of the tumour. Wide surgical excision with safe margins is an appropriate treatment for low- to intermediate-grade tumours, together with neck dissection if lymph nodes are involved. Because cystadenocarcinomas are rare, very limited follow-up data are available. Most reports, however, support the opinion that majority are low-grade malignancies with excellent prognosis after appropriate surgical treatment: superficial parotidectomy, glandectomy and wide excision for tumours of the parotid, submandibular and minor glands, respectively. Occasional high-grade cystadenocarcinomas require adjuvant radiation therapy.

15.4 Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

The WHO defines mucinous adenocarcinoma as ‘a malignant epithelial tumour composed of epithelial clusters within large pools of extracellular mucin. The mucin component occupies the majority of the tumour’ [63]. Others prefer to use the term ‘colloid carcinoma’ for the same entity [47]. By definition, mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma should have more than 50 % of a typical colloid component with large amount of abundant extracellular mucin. The malignant epithelial salivary tumours with less than 50 % of cystic mucinous component are better classified as mucinous cystadenocarcinomas [47]. Primary minor salivary gland adenocarcinoma with prominent signet ring cells and mucus production and with microcystic and papillary growth pattern with prominent intracytoplasmic lumina was first described by de Araujo and associates [42]. Later, signet ring cell carcinoma, characterised by the presence of isolated tumour cells with intracytoplasmic mucus vacuoles, was described in the minor salivary glands of seven patients [46]. Signet ring cell differentiation may occasionally be found in mucinous (colloid) carcinoma of the salivary glands [45].

15.4.1 Epidemiology and Clinical Features

Neoplasms with prominent mucin production and signet ring cell component in the head and neck area are extremely rare, and generally metastatic carcinoma from distant sites, such as the breast, colorectal region and lung, must be considered. Primary mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma of the major and minor salivary glands is a rare neoplasm with only about 20 cases reported in the literature so far [38, 39, 43, 46, 49, 50, 54]. Most tumours arise in the minor salivary glands, namely, in the glands of the palate, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth and base of the tongue. Only few cases have been described in the parotid gland [62]. The most common presenting feature is a slowly growing painless swelling of variable duration from several months up to 11 years. The intraoral tumours may be ulcerated. Tumours range in size from 0.5 to 7.6 cm in diameter with most cases being between 2 and 4 cm.

15.4.2 Histopathology

The tumour is often nodular and ill defined. The cut surface is whitish grey with multiple cystic spaces containing gelatinous secretory material. Mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands is histologically identical with breast and colorectal analogues. The tumour is composed of round- or irregular-shaped neoplastic cell nests, clusters and islands floating in mucus-filled cystic cavities with abundant extracellular mucin in direct contact with stroma (Fig. 15.20). The mucin lakes contain malignant epithelium arranged in small nests, glands or single tumour cells. The tumour cells are cuboidal, columnar or irregular in shape, usually with clear cytoplasm and dark-stained centrally located nuclei. Mitotic figures are rare. Both intracytoplasmic and extracellular mucin show positive staining for periodic acid-Schiff, alcian blue and mucicarmine. Signet ring cell carcinoma is composed of neoplastic cells with large intracytoplasmic vacuole that compresses the nucleus into the form of crescent. Unusual case of micropapillary cystadenocarcinoma arising in mucinous cystadenoma of the parotid gland has been described [56].

Fig. 15.20

The mucin lakes contain malignant epithelium arranged in small nests, glands or single tumour cells

15.4.3 Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes mucinous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), mucin-rich salivary duct carcinoma, metastatic mucin-producing carcinomas and mucin extravasation phenomenon. Cystadenoma can be separated from mucinous adenocarcinoma by its lack of stroma invasion and cellular atypia [41].

Cystadenocarcinomas of the salivary glands are a rare low-grade neoplasms characterised by prominent cystic appearance. They often have complex papillary architecture with infiltrative growth and absence of myoepithelial cells [36, 44, 51, 53, 59] and may have mucinous differentiation [52, 58, 64]; however, the presence of mucus-filled lakes of extracellular secretory material is not the feature. In contrast, mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma reveals a prominent presence of tumour cell clusters floating in mucus-filled cystic cavities separated by fibrous connective tissue septa. Low-grade MEC may have cystopapillary structures and can also show extravasated mucin but can be differentiated from cystadenocarcinomas and mucinous carcinoma, respectively, by presence of mucus-producing cells intermingled with epidermoid cells lining the cysts and by presence of intermediate cells arranged in solid structures. Moreover, in a significant number of cases, mucoepidermoid carcinoma harbours a recurring t(11;19)(q21;p13) CRTC1-MAML2 (known also as MECT1-MAML2) translocation [60]. Mucin-rich salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) will always have areas with histological appearance typical of SDC [61]. Subsequent to the description of signet ring cell (mucin producing) adenocarcinoma [46], other primary salivary gland tumour types, such as salivary duct carcinoma [55], mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma [37], have been described to contain signet ring cell component. Metastatic tumours can be separated by clinical history and evaluation. Whilst clinical history is useful, metastatic mucin-rich carcinomas may be differentiated from primary salivary by immunohistochemical findings; in particular CK20, CDX-2, ER, PR and TTF1 are not expressed in primary salivary colloid and mucinous adenocarcinoma. Mucin extravasation phenomenon contains pools of interstitial mucin, often with inflammatory infiltrate and fibrosis. In contrast to mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, the epithelium is bland and not found within the mucin pools [57, 65]. In addition, recently a small series of myoepithelial tumours both benign and malignant containing intracellular mucin were recognised [40, 48].

15.4.4 Treatment and Prognosis

Mucinous adenocarcinoma has a propensity for local recurrence and significant risk of lymph node metastases; therefore the tumour should be considered as a high-grade malignancy. Wide surgical resection with free margins and cervical lymph node dissection seems to be the best therapy. Adjuvant radiotherapy depending on tumour stage should be also considered [47, 63].

15.5 Low-Grade Salivary Duct Carcinoma (Low-Grade Cribriform Cystadenocarcinoma)

Low-grade salivary duct carcinoma (LG-SDC) is a rare neoplasm characterised by a predominant intracystic and intraductal growth, luminal ductal phenotype and bland microscopic features. This tumour entity was first recognised by Delgado and associates as a low-grade indolent carcinoma of the salivary glands that resembles the spectrum of breast lesions from atypical ductal hyperplasia to micropapillary and cribriform low-grade breast carcinoma in situ [78]. Although Delgado and associates have documented the prevailing intraductal growth pattern, the 2005 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors adopted the name ‘low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma’ and regarded it as a variant of cystadenocarcinoma. The relationship between low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma and salivary duct carcinoma remains unclear, and controversy in terminology has yet to be resolved [69].

15.5.1 Epidemiology and Clinical Features

LG-SDC is an exceedingly rare neoplasm with approximately 39 cases published in the English literature since 1996 [68, 70, 72, 78, 88, 89, 93]. LG-SDC affects adults with a wide age spectrum (range 27–93, mean 61.4, median 62.5 years, respectively). Most LG-SDCs affect the parotid gland (84.6 %) with only a few arising in the intraparotid lymph nodes [103], accessory parotid gland [92], submandibular gland (2.6 %) and minor salivary glands [83, 102]. The average age of patients is 64 years (range 32–93). LG-SDC shows slight female predominance 1.5:1. Patients usually present with an asymptomatic and slow-growing mass. No facial nerve paralysis has been recorded in any patient although one patient complained of paraesthesia along the upper neck and ear [104].

15.5.2 Histopathology

Grossly, LG-SDCs are well circumscribed, nonencapsulated and lobulated with cystic spaces of varying size, containing serous to haemorrhagic fluid, some of which are completely or partly filled with neoplastic tissue. Tumour size ranges up to 4 cm.

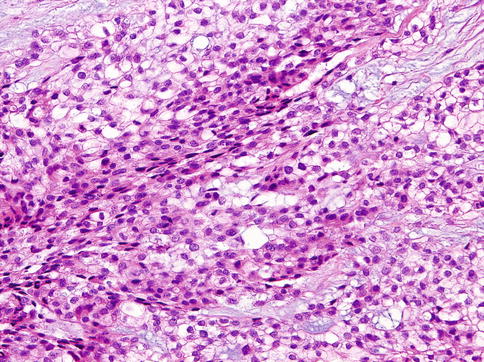

Microscopically, LG-SDC is a well-circumscribed mass that generally displaces rather than truly invades salivary gland tissue. It is composed of solid, cribriform and cystic islands of cells with anastomosing intracystic micropapillary structures arranged in so-called Roman bridges (Fig. 15.21). At low-power magnification, LG-SDC exhibits multiple cysts of variable size and smaller ducts (Fig. 15.22). The cysts and ducts display a diverse architecture with multiple patterns and a heterogeneous luminal epithelial proliferation showing a ductal phenotype, ‘pseudocribriform’ proliferations with irregular slits (Fig. 15.23), micropapillae with anastomosing epithelial tufts (Fig. 15.24), fibrovascular cores and solid areas. Mucinous secretion may be seen in the glandular lumens.

Fig. 15.21

LG-SDC is composed of solid, cribriform and cystic islands of cells with anastomosing intracystic micropapillary structures arranged in so-called Roman bridges

Fig. 15.22

At low-power magnification, LG-SDC exhibits multiple cysts of variable size and smaller ducts

Fig. 15.23

The cysts and ducts display a diverse architecture with multiple patterns and a heterogeneous luminal epithelial proliferation showing a ductal phenotype with ‘pseudocribriform’ proliferations

Fig. 15.24

Micropapillae with anastomosing epithelial tufts are seen

At high-power magnification, LG-SDCs show bland but heterogeneous cytological features. The cells have low-grade round to oval nuclei which may contain finely dispersed or dark condensed chromatin and clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 15.25). Elongated ‘streaming’ cells are also seen. Prominent nucleoli are absent in the majority of the cells, but small eosinophilic nucleoli can be seen. Mitotic rate is low. Most neoplastic islands are surrounded by intact rim of flattened myoepithelial cells. Perineural and angiolymphatic invasion are absent.

Fig. 15.25

At high-power magnification, LG-SDC shows bland but heterogeneous cytological features. The cells have low-grade round to oval nuclei and clear to eosinophilic granular cytoplasm

Apocrine differentiation with apical snouts and cytoplasmic microvacuoles is occasionally present [78, 104]. Some tumours contain fine lipofuscin-like, yellow to brown pigment within the intracytoplasmic vacuoles [70, 78]. Psammoma bodies and microcalcifications have been described in several cases [70, 104]. Secondary changes, such as haemorrhage, cholesterol clefts and dystrophic calcification, are relatively common.

LG-SDC generally lacks cellular or nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, significant mitotic activity and necrosis. However, transition to limited areas of high-grade cytological atypia, including necrosis, has been illustrated [70, 78, 102, 104]. Focal invasive carcinoma or microinvasion has been reported in nine cases of LG-SDC [70, 72, 78, 88, 92, 104], although the presence of invasion does not seem to adversely affect the patients’ outcome. In six of these nine cases, the invasion was described as limited or focal; in two cases, the invasive component was called ‘adenocarcinoma NOS’ [83, 92] and in one case was an adenosquamous carcinoma [104]. The latter case had metastatic adenosquamous carcinoma in multiple periparotid and cervical lymph nodes.

15.5.2.1 Immunohistochemistry and Ultrastructural Findings

The predominant cells in LG-SDC have a distinctive ductal phenotype and express broad spectrum cytokeratins (AE1-AE3); cytokeratins CK7, CK8, CK18 and CK19; and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). The ductal cells of LG-SDC also show diffuse and strong nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity with S-100 protein. In only three cases has S-100 protein been reported as negative [68, 104]. Smooth muscle actin (SMA), calponin, p63 and cytokeratin 14 (CK14) clearly demonstrate a continuous layer of myoepithelial cells rimming the ducts and cyst spaces (Fig. 15.26). High molecular keratin (HMWK, CK34bE12) is positive in both ductal and non-neoplastic myoepithelial neoplastic cells. In tumours with areas of invasion, this myoepithelial layer appeared discontinuous [70]. MIB1 proliferation index is less than 1 %. Oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), androgen receptors (AR) and HER2/neu are absent [70, 89].

Fig. 15.26

Most neoplastic islands are surrounded by intact rim of flattened myoepithelial cells clearly demonstrated by cytokeratin 14 immunoexpression

15.5.3 Differential Diagnosis

The predominant multicystic architecture of LG-SDC and bland morphology raise a wide differential diagnosis, which includes cystadenoma, sclerosing polycystic adenosis, recently described benign lesions, ductal adenoma with striated duct differentiation [106] and intercalated duct hyperplasia/adenoma [105].

Low-grade malignant tumours considered in differential diagnosis include cystadenocarcinoma, salivary duct carcinoma in situ/high-grade intraductal carcinoma, conventional salivary duct carcinoma, papillary-cystic variant of acinic cell carcinoma and mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) of the salivary glands.

15.5.3.1 Cystadenoma

Cystadenomas are uncommon neoplasms of the salivary glands. They are well-circumscribed and composed of variable-sized cystic spaces. The lining epithelium also has a variable appearance, which can be flat, cuboidal or columnar, and can have oncocytic, mucinous, epidermoid and apocrine changes. There is no cellular atypia, solid growth, necrosis or mitoses. In a rare case, intraductal or intracystic epithelial proliferation with architecture resembling breast atypical ductal hyperplasia was described [79], but unlike LG-SDC, this case was reported to be negative for S-100 protein and GCDFP-15 and showed only focal positivity for CK19 and HMWK.

15.5.3.2 Sclerosing Polycystic Adenosis

Sclerosing polycystic adenosis (SPA) is a mass lesion of the salivary gland resembling breast fibrocystic disease or sclerosing adenosis. Initially regarded as a reactive or inflammatory process, the demonstration of clonality by human androgen receptor (HUMARA) gene testing suggests that SPA represents a neoplastic lesion [98]. SPA is well circumscribed and unencapsulated and is composed of a ductal and acinic proliferation in a hypocellular sclerotic background forming sclerotic nodules [101] which is not seen in LG-SDC. The ducts of SPA frequently show cystic changes and may have apocrine, mucinous, vacuolated and foamy appearance. Epithelial hyperplasia, dysplasia or even carcinoma in situ of the ductal epithelium has been reported [97]. The lobules in SPA maintain a layer of myoepithelial cells demonstrated by SMA, calponin and S-100 protein [97, 98]. SPA develops local recurrence in around one-third of cases [81, 82], but no metastasis or mortality has been reported.

15.5.3.3 Ductal Adenoma with Striated Duct Differentiation (DAS)

Ductal adenoma with striated duct differentiation is an extremely rare lesion characterised by a pure ductal component with striated duct differentiation lacking a continuous layer of myoepithelial cells [106]. Unlike LG-SDC, DASs are grossly solid and encapsulated. Microscopically, DASs are comprised of closely arranged ducts separated by a delicate intervening vasculature. Although cystic ducts are seen in DAS, these lesions lack the cribriform, pseudocribriform or micropapillary architecture of LG-SDC; moreover they do not have a continuous myoepithelial layer when stained with SMA, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC) and calponin [106].

15.5.3.4 Intercalated Duct Lesions (IDLs)

Intercalated duct lesions are an uncommon group of small lesions displaying intercalated duct phenotype ranging from hyperplasia to adenoma [105]. Although some of the IDLs may form detectable masses, most often they are found in association with other salivary gland tumours, such as basal cell adenoma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma and basal cell adenocarcinoma. IDLs can be unifocal, multifocal or diffuse and nonencapsulated or encapsulated. In contrast to the multicystic appearance of LG-SDC, IDLs are composed of small ducts with a mixture of bland ductal, acinic and mucus cells surrounded by a continuous layer of myoepithelial cells [105].

15.5.3.5 Cystadenocarcinoma

Cystadenocarcinomas of the salivary glands are a rare and morphological heterogeneous group of neoplasms characterised by prominent cystic appearance. They often have complex papillary architecture with infiltrative growth and absence of myoepithelial cells [66, 80, 84, 87, 95]. Although most cystadenocarcinomas are low-grade malignancies [66, 80, 84], others exhibit large cuboidal or columnar cells with moderate to high nuclear atypia, prominent nucleoli and frequent mitoses [80, 86, 95], and lastly, some are best classified as mucinous cystadenocarcinoma [86, 94, 107].

15.5.3.6 Salivary Duct Carcinoma In Situ/High-Grade Intraductal Carcinoma (HG-IDC)

Although not formally recognised in the 2005 edition of the WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors, there are rare but well-documented cases of ‘high-grade intraductal’ carcinomas of the salivary glands [67, 71, 73], or ‘salivary duct carcinoma in situ’ [96]. High-grade intraductal carcinoma and salivary duct carcinoma in situ (HG-IDC) share with LG-SDC many features including partly cystic appearance; cribriform, solid and micropapillary patterns; and neoplastic cells with ductal phenotype surrounded by a layer of myoepithelial cells. The differences between LG-SDC and HG-IDC are nuclear grade and the presence of necrosis [73]. Although the numbers of published cases of HG-IDC is quite small, the expression of S-100 protein may help to separate these two lesions since HG-IDCs have been either negative or only partially positive for S-100 protein [73, 96].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree