and Alena Skalova2

(1)

Departamento de Ciências Biomédicas e Medicina, Universidade do Algarve, Faro, Portugal

(2)

Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty Charles University, Plzen, Czech Republic

6.2 Oncocytoma

6.5 Lymphadenoma

6.6 Cystadenoma

6.7 Ductal Papilloma

6.8 Sialolipoma

6.9 Keratocystoma

A guide for the incidence and anatomical site of adenomas is outlined in Tables 6.1 and 6.2. These data are collected from only a few large recent series from different parts of the world and show wide variations between them. These studies primarily comprise intraoral tumours, and the compiled data will thus only serve as a rough guideline. For example, approximately 80 % of basal cell adenomas occur in major salivary glands, and in studies comprising only intraoral tumours, the true relative frequency of basal cell adenoma in comparison with other adenomas will not be reflected. However, these studies as well as others clearly indicate that adenomas other than pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin tumour are all rare. In a non-Asian population, canalicular adenoma is the most common adenoma of the nine different types discussed in this chapter and matches approximately the frequency of myoepithelioma (see Chap. 4). The clinical relevance of correct diagnosis of adenomas described here can briefly be outlined as follows:

Table 6.1

1,157 salivary adenomas of intraoral minor salivary glandsa. The figures are given as percentage of benign tumours in each published series

Jones et al. 2007 | Buchner et al. 2007 | Wang et al. 2007 | Yih et al. 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

No. of benign tumours | 481 | 224 | 333 | 119 |

Basal cell adenoma | 7.7 | 2.7 | 1.2 | – |

Oncocytoma | 1.0 | – | – | 0.9 |

Canalicular adenoma | 7.3 | 10.2 | – | 21.0 |

Sebaceous adenoma | 0.2 | – | – | – |

Cystadenoma | 3.1 | 10.7 | 1.8 | – |

Ductal papilloma | 2.2 | 7.5 | 0.6 | – |

Pleomorphic adenoma | 68.5 | 66.7 | 81.7 | 78.1 |

Warthin tumour | 7.1 | – | 0.3 | – |

Myoepithelioma | 2.9 | 2.2 | 14.4 | – |

100 % | 100 % | 100 % | 100 % |

Table 6.2

Location of 675 intraoral salivary adenomas (From Buchner et al., Wang et al.a, Yih et al.)

Type | Palate | Lip | Buccal mucosa | FOM | Retromolar region | Tongue | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Upper | Lower | |||||||

BCA | 3 | 6 | – | 1 | 10 | |||

CA | 7 | 37 | – | 4 | 48 | |||

CYA | 14 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | – | 5 | 30 |

DP | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | – | 1 | 19 |

31 | 46 | 5 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 107 | |

PA | 359 | 78 | 7 | 63 | 1 | 5 | – | 513 |

WT | 1 | 1 | ||||||

MYO | 46 | 2 | – | 4 | 1 | – | 1 | 54 |

1.

In the case of lymphadenoma, sebaceous adenoma, sialolipoma and keratocystoma, too few cases have been reported in the literature so to correctly estimate the risk for recurrence or malignant transformation.

2.

Oncocytoma, cystadenoma, intraductal papilloma and sialadenoma papilliferum are very unlikely to recur.

3.

The membranous type of basal cell adenoma and the inverted papilloma type of the ductal papillomas tend to recur, whilst the other types of basal cell adenoma and canalicular adenoma rarely recur.

4.

Malignancy may on very rare occasions arise in all four subtypes of basal cell adenoma, from oncocytoma and cystadenoma, but very unlikely, or not at all, arise in canalicular adenoma and ductal papillomas.

The histological recognition of salivary adenomas other than pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin tumour, and to a certain extent also myoepithelioma, is notoriously difficult. Over the years, there have also been numerous terms and classification schemes. Particularly the differentiation between benign and malignant intraoral minor salivary tumours can be troublesome, where polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma are the most common malignant counterparts. This fact was recently highlighted by Turk and Wenig, who described various diagnostic pitfalls and also suggested a diagnostic approach and terminology [162]. In general surgical pathology practice, we are inclined to a certain degree to agree with Zarbo and associates in their statement ‘To wit, we believe it does not matter what these tumours are called as long as they are recognized and designated benign and the adequacy of excision is noted’ [177].

6.1 Basal Cell Adenoma

Basal cell adenoma (BCA) consists of basaloid cells arranged in four different cellular growth patterns. There is no myxoid, mucoid or chondroid component as seen in pleomorphic adenoma and occasionally in myoepithelioma. Basal cell adenoma with three basic histological patterns was first described in 1967 by Kleinsasser and Klein who considered the tumours to be ‘monomorphic and isocellular’ [90]. In the first WHO salivary gland tumour classification in 1972, basal cell adenoma was barely recognised but described as one example of monomorphic adenoma, other than Warthin tumour and oncocytoma [159]. In the 2nd WHO classification of 1991, the definition of BCA was refined and clearly laid out. The four patterns of basal cell adenoma were described as solid, trabecular, tubular and membranous. The association with dermal cylindroma (turban tumour), trichoepithelioma or eccrine spiradenoma of the scalp, as well as the occurrence of malignant transformation to basal cell adenocarcinoma, was also mentioned [147]. In the latest WHO classification, the histological criteria for basal cell adenoma remain the same [39]. In 1991, the frequency of basal cell adenoma was estimated to be 1–2 % of all salivary gland tumours and 70 % being located in the parotid gland [147]. Due to the worldwide recognition of the new classification with basal cell adenoma no longer included in a group of monomorphic adenomas but being a separate entity, the comparison of epidemiological data in studies performed before 1991 and afterwards may not correlate well. In the latest WHO classification of 2005, the epidemiological data remain approximately the same with basal cell adenoma accounting for 1.8–5 % of all salivary gland tumours. It is predominantly a tumour of major salivary glands with approximately 75 % of cases found in the parotid glands and 5 % in the submandibular glands. The upper lip is the most common site when it is of minor salivary gland origin. Although three of the six studies from which the data were compiled in the 2005 WHO classification were published well before the second classification in 1991, they originated from centres with leading knowledge and experience of the basal cell adenoma entity to come [39].

Basal cell adenoma is usually a small, usually less than 3 cm, and well-circumscribed nodule having a smooth and sometimes glistening capsule. In this respect, it is clinically very similar to pleomorphic adenoma. It tends to occur in elderly patients with a peak in the seventh decade and with a 2:1 female predilection and hence in a rather older age group than pleomorphic adenoma [146]. The tumour consists of eosinophilic basaloid cells with indistinct cell borders and round to oval nuclei. The basaloid cells in BCA comprise three types of cells: ductal cells (sparse or absent in the solid type of BCA), ductal basal cells and myoepithelial cells. At least four growth patterns are recognised and often combinations thereof may be seen in the same tumour.

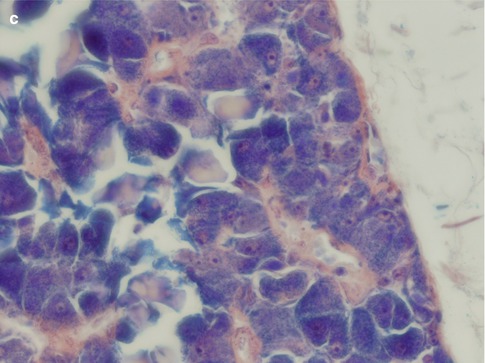

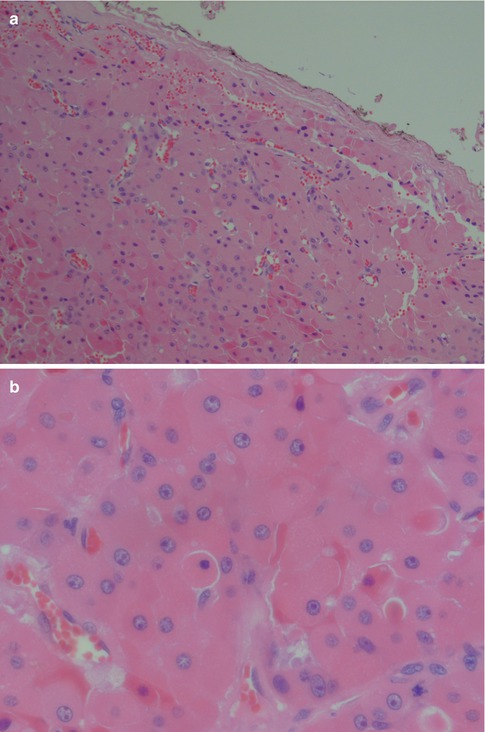

The solid type of basal cell adenoma sometimes resembles a basal cell carcinoma of the skin. There are solid nests of crowded basaloid tumour cells surrounded by a palisading outer layer of columnar or cuboidal cells. Squamous metaplasia can occasionally be seen in basal cell adenoma, hence another feature in common with skin basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 6.1). The trabecular type of BCA has basaloid cells arranged in strands and cords of varying thickness, although often rather thin and narrow. These cords are separated by a fibrous sometimes cellular stroma. Occasionally the stromal cells can be spindle-shaped and myoepithelial in nature [37]. In areas the stroma may be vascular and with thin cords the features may mimic a canalicular adenoma (see below). All basal cell adenomas are well circumscribed or encapsulated (Fig. 6.2).

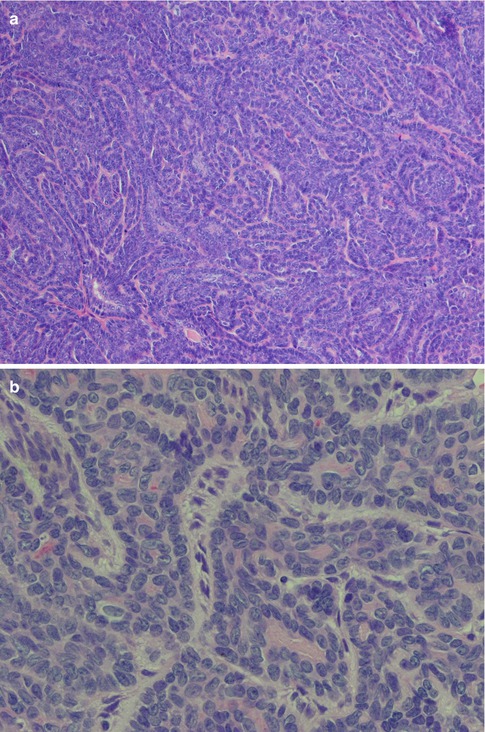

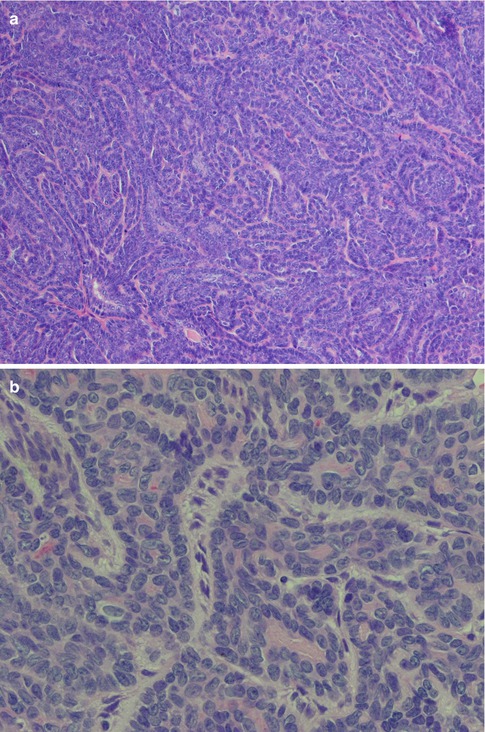

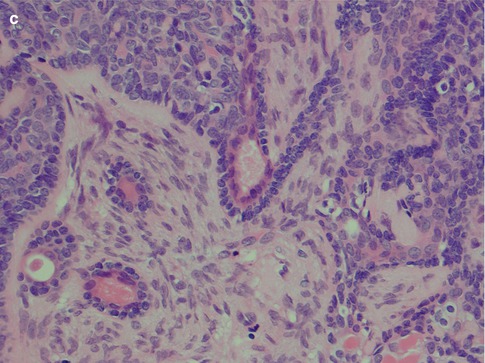

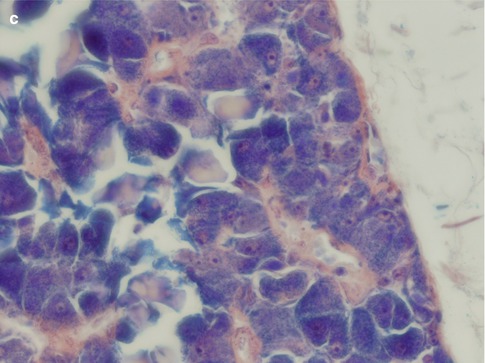

Fig. 6.1

Basal cell adenoma, solid type. (a) Solid nests of cells only separated by thin cords of stroma. (b) Palisading of nuclei in peripheral cells. (c) Squamous metaplasia in solid type BCA

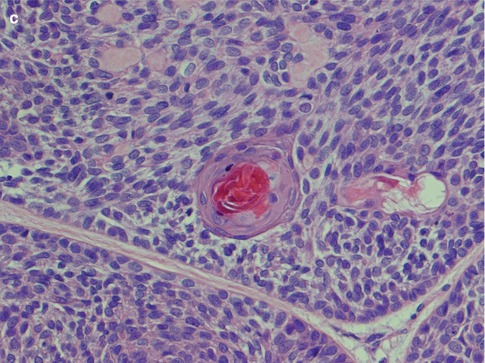

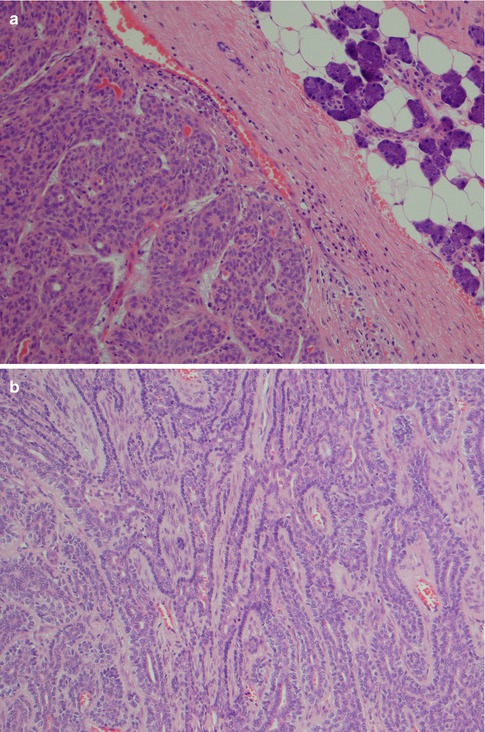

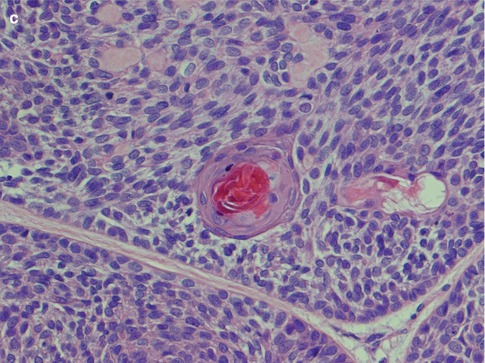

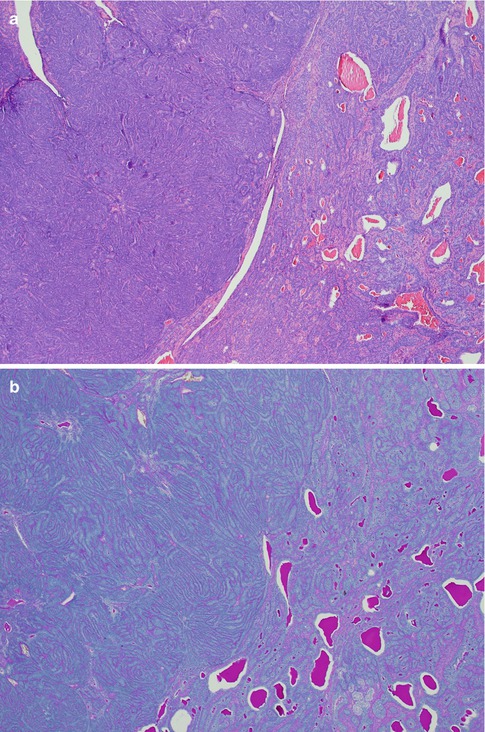

Fig. 6.2

(a) Trabecular BCA with a thick surrounding capsule. (b) Trabecular type BCA with anastomosing strands and cords of basaloid cells. Palisading of nuclei in the outer cells of the cords

The tubular type of BCA has strands of basaloid cells with numerous small duct lumina lined by cuboidal, often eosinophilic cells. The lumina often contain a PAS-positive material. Some tubular BCAs can be oncocytic (Fig. 6.3). A recent study has demonstrated that BCA shares immunophenotypical features with normal intercalated ducts and suggests that some BCAs may arise via intercalated duct lesions [120]. Most often basal cell adenomas are not purely trabecular or tubular but contain variable proportions of both elements and referred to as tubulo-trabecular BCA. The inner ductal cells typically stain for CK7. The outer myoepithelial cells are positive for p63 but rarely for SMA [99]. The stroma can occasionally be very cellular and the cells may appear spindle-shaped (Fig. 6.4). The trabecular and tubular types are more common than the solid and membranous types. Most often the different patterns are intermingled with each other, but they can also be rather sharply delineated from each other. Usually one growth pattern predominates and all four types of BCA can be cystic (Fig. 6.5). Adenoid cystic carcinoma may occasionally constitute a differential diagnosis. The identification of a capsule, no or very little atypia present, and a low proliferation index as measured by Ki-67, will all strongly favour a basal cell adenoma.

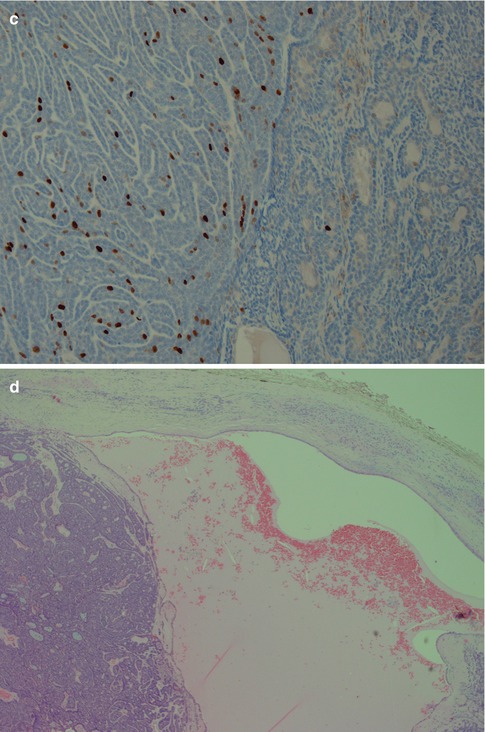

Fig. 6.3

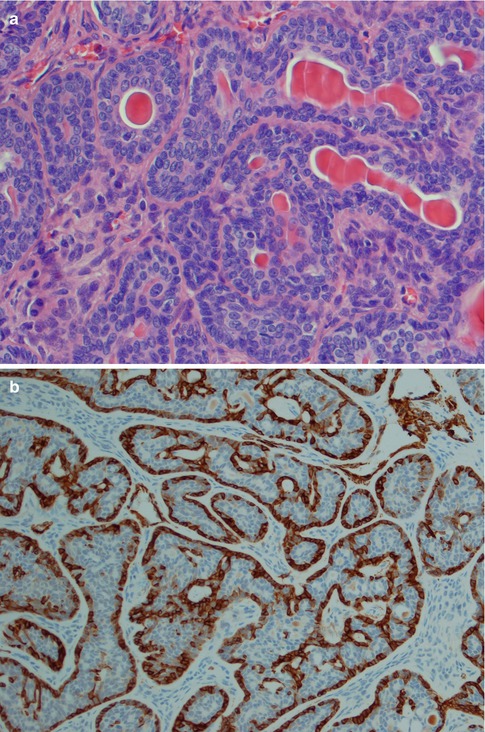

(a) Tubular BCA. (a) Numerous ductal structures surrounded by basaloid cells. (b) CK7 stain highlights the inner ductal cells. (c) Inner eosinophilic ductal cells. Note the cellular stroma partly consisting of spindle-shaped cells

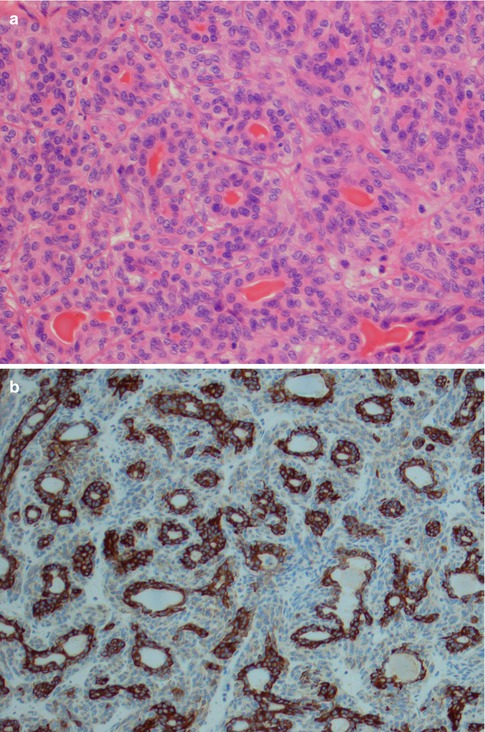

Fig. 6.4

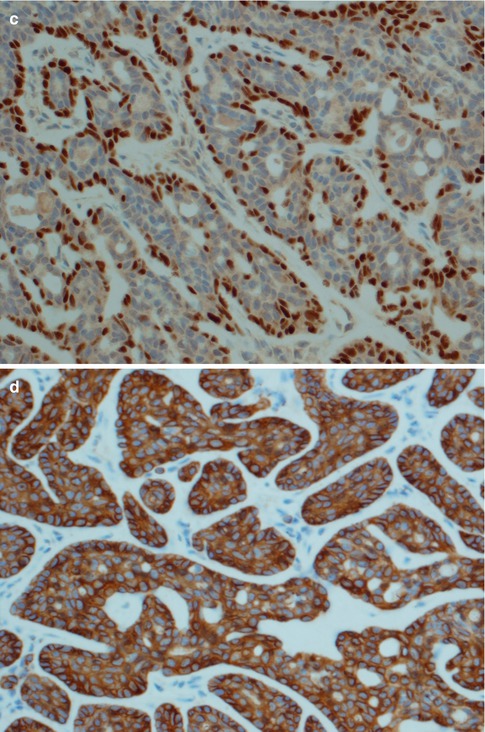

BCA, tubulo-trabecular type. (a) Mixture of tubules and trabeculae. (b) Outer myoepithelial cells positive for SMA. (c) Strong p63 expression in outer basal/myoepithelial cells. (d) CK14, on the contrary, tends to stain both the basaloid and ductal cells, as well as surrounding myoepithelial cells

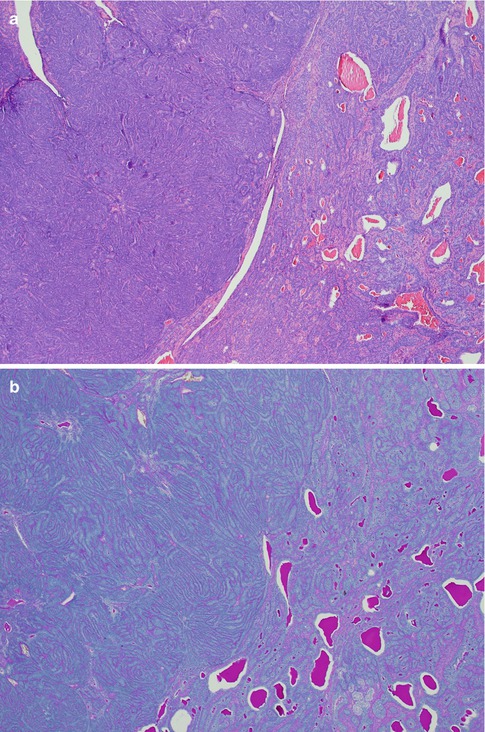

Fig. 6.5

(a) Trabecular/tubular basal cell adenoma containing a well-delineated nodule with solid growth pattern (left). (b) PAS-positive lumina (mucicarmine negative) in trabecular/tubular areas but virtually negative in the solid areas. (c) Considerably higher Ki-67 index in the solid part. (d) Cystic tubulo-trabecular BCA

The membranous type of BCA (dermal anlage type, dermal analogue tumour) was first reported by Drut in 1974 when describing a parotid tumour as a ‘cutaneous type of cylindroma’ and a few years later designated membranous basal cell adenoma by Headington et al. in 1977. It was termed ‘dermal analogue tumour’ by Batsakis and Brannon in 1981 but in the 2nd WHO classification referred to as membranous type basal cell adenoma [12, 42, 70, 147]. Membranous BCA is characterised by multiple nests or islands of basaloid epithelial cells having palisading of peripheral cells and an excessive hyaline basal membrane. There are hence thick bands of hyaline material surrounding the epithelial islands. Both sebaceous and epidermoid differentiation can be seen in the cell islands. Membranous BCAs are multilocular, often multicentric and rarely encapsulated, and therefore an infiltrative growth pattern is imparted to this type of BCA. The membranous BCA resembles the dermal cylindroma and not infrequently coexists with tumours of the skin, e.g. eccrine cylindroma or trichoepithelioma of the scalp (turban tumour) (Fig. 6.6). Immunohistochemically, all basal cell adenomas will exhibit ductal and some degree of myoepithelial differentiation and are positive for keratin markers such as CK7 and others but also, contrary to canalicular adenoma, variable positive for myoepithelial markers (SMA, vimentin, p63, S-100, etc.). It is worth to recall that both ductal basal cells and myoepithelial cells stain positive for p63 [17, 106, 177].

Fig. 6.6

Membranous type of BCA with a thick layer of hyaline material surrounding each lobule of basaloid cells

The histological subclassification into the four types described above has no clinical information or value apart from the case of membranous basal cell adenoma. The membranous type of basal cell adenoma has a recurrence rate of as much as 25 % [102], whilst the other types can be regarded as non-recurrent tumours. On rare occasions, malignancy may develop from a basal cell adenoma (any subtype) and usually as a basal cell adenocarcinoma or adenoid cystic carcinoma (see Chap. 15) but also non-basaloid carcinomas such as salivary duct carcinoma and intracapsular adenocarcinoma NOS and intracapsular myoepithelial carcinoma. In one series, malignant transformation occurred inasmuch as 4.3 % basal cell adenomas [122].

6.2 Oncocytoma

Oncocytomas (oncocytic or oxyphilic adenomas) are rare tumours consisting of oncocytes which are large polyhedral cells with bright eosinophilic cytoplasm. This cell type was first described, evidently independently, by Schaffer and Koschier in 1897. They described this type of cells as being single, in clusters and in papillary cystic formations in the upper aerodigestive tract [92, 143]. In 1927, Zimmermann termed these cells pycnocytes because of the appearance of the nucleus [178]. The nuclei are characteristically small and dark (dark cells) but there are also cells with oval and vesicular nuclei (light cells). The tumour is usually surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule, and the eosinophilic (oncocytic) cells are granular due to a high content of mitochondria. Special stain with phosphotungsten acid-haematoxylin (PTAH) will highlight the granular positivity of mitochondria of the oncocyte. There tend to be some histological differences between minor and major salivary gland oncocytes. Minor salivary oncocytes often have cilia present, and major salivary oncocytes have more perfectly rounded nuclei. The major salivary oncocytes also form cuboidal binucleate cells, long tapered cells and cuboidal ‘pycnocytes’ with condensed nuclei [21]. Oncocytic cells are normally found amongst the salivary ducts and the epithelial acinar cells, likely as a result of a metaplastic process. Oncocytosis may occur in two forms, diffuse oncocytosis and multifocal nodular oncocytic hyperplasia (see Chap. 1). The separation between multifocal nodular oncocytic hyperplasia from multinodular oncocytoma is not always easy and sometimes perhaps not even possible due to that of the two entities may overlap histologically [18, 55, 75, 156]. It is also possible that oncocytoma in some instances may originate from a pre-existing multifocal nodular oncocytic hyperplasia. Furthermore, bilateral parotid oncocytomas are said to occur in 7 % of cases and in one case arising in a background of bilateral oncocytic nodular hyperplasia [75, 76, 157, 164]. Synchronous oncocytoma and Warthin tumour are also known to occur [5].

The first case of a salivary tumour consisting entirely of oncocytes appears to be the case described by McFarland in 1928 [112]. Oncocytic changes and tumours were more widely recognised after Hamperl’s detailed description of the oncocyte in 1931, and the term oncocytoma was coined by Jaffé a year later [65, 81]. In 1962, Hamperl reported the first larger series and review of the literature compiling 47 cases of oncocytoma [67]. Foci with oncocytic change occur more commonly in other salivary gland tumours such as Warthin tumour, pleomorphic adenoma and basal cell adenoma than does oncocytoma itself. The concept of oncocytic and oncocytoid salivary gland tumours was described in detail by Paulino and Huvos in 1999 [133]. Oncocytoma is rare and represents less than 1 % of the salivary gland tumours. Oncocytoma occurs primarily in elderly patients with approximately 85 % in the parotid gland, 10 % in the submandibular gland and 5 % in minor salivary glands [18, 21, 47, 52, 75, 130, 160]. Laryngeal oncocytoma is a misnomer as most cases reported have been oncocytic cystadenoma or cysts with oncocytic metaplasia. In fact, solid laryngeal oncocytic tumours are not known to occur in humans [22, 103].

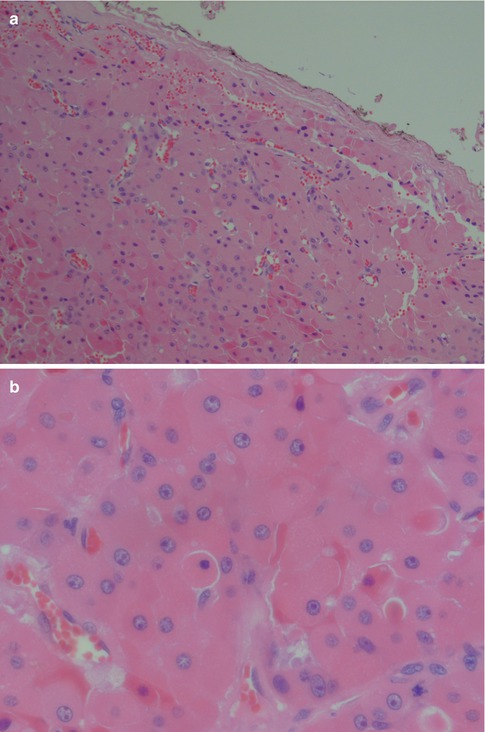

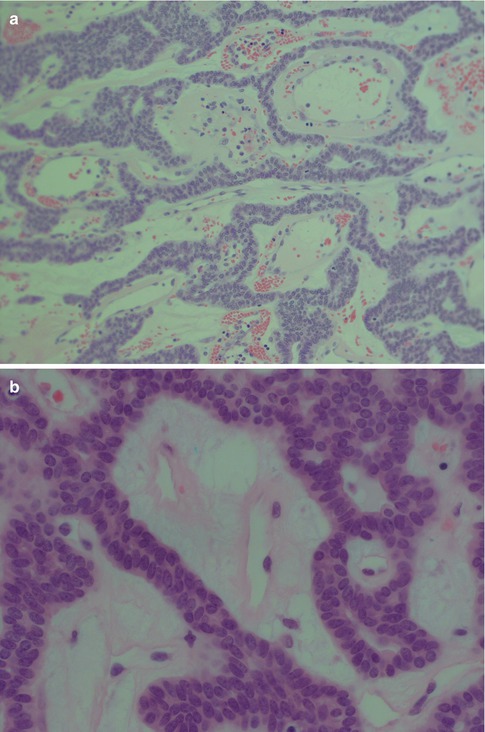

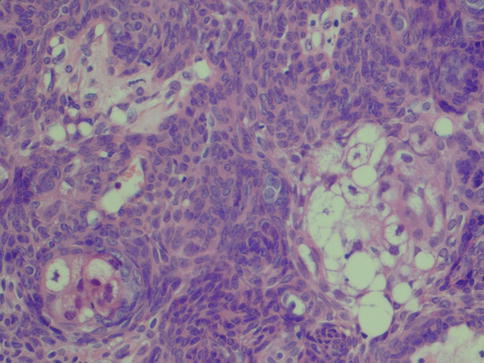

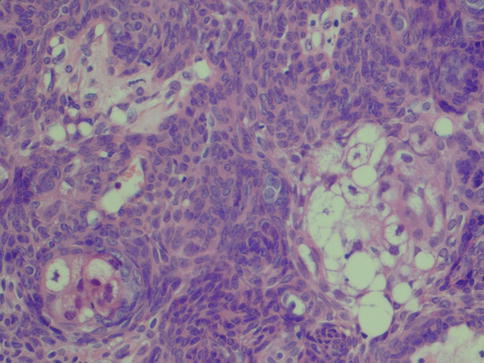

The histology of the oncocytic cell is well known and poses no dilemma when appearing with its normal bright eosinophilic cytoplasm and smallish nucleus. The diagnosis of oncocytoma requires a well–demarcated mass of these cells growing in a solid, trabecular or tubular pattern. Multifocal nodular oncocytic hyperplasia, on the other hand, consists of nonencapsulated nodules of oncocytic cells (see Chap. 1). The light cells with their vesicular nuclei usually predominate in number over the dark cells with their small pycnotic nuclei. There is no atypia. Thin strand of fibrovascular stroma is seen in between and separating the rather the uniform sheets of oncocytic cells (Fig. 6.7). Rather frequently, there is a mixture of typical eosinophilic cells and clear cell oncocytes. The latter appear optically clear due to intracytoplasmic glycogen deposition and/or fixation artefact. Tumours that predominantly or entirely consist of clear oncocytic cells are referred to as clear cell oncocytoma. Clear cell oncocytoma is the only clear cell salivary neoplasm that is benign. Local recurrence of oncocytoma is very rare and so is malignant transformation into oncocytic carcinoma (see Chap. 15).

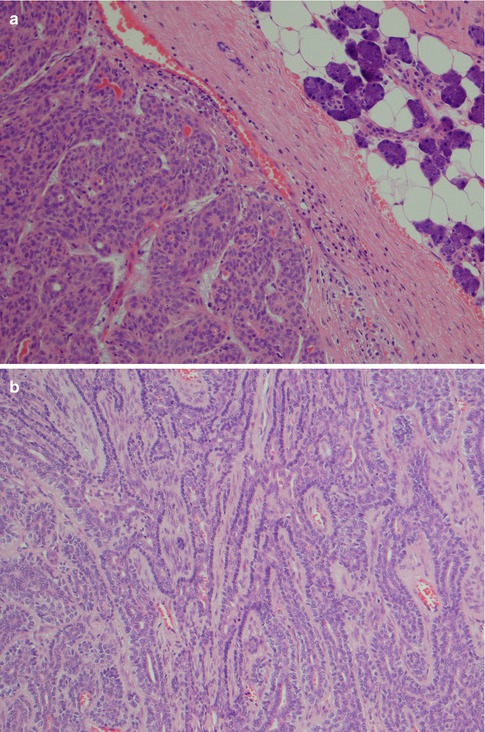

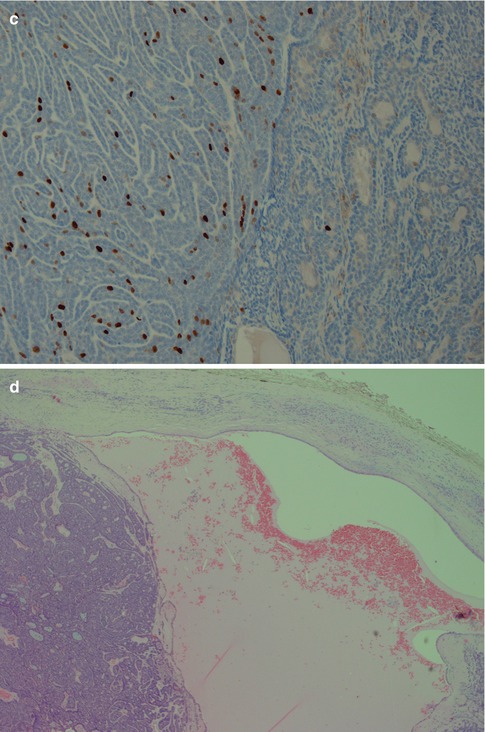

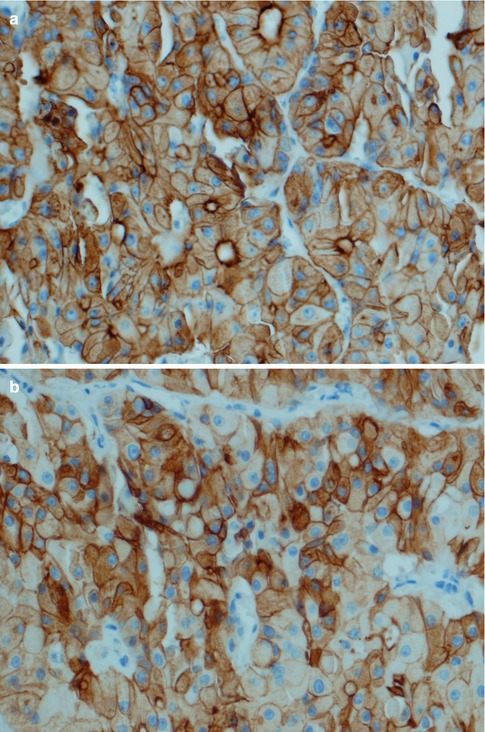

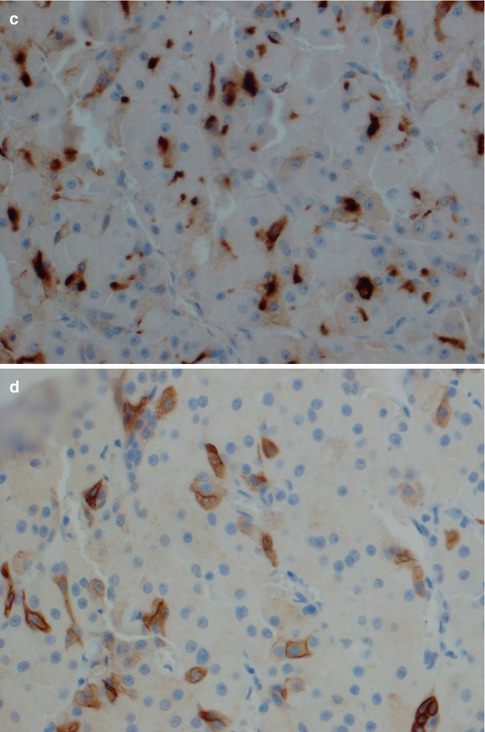

Fig. 6.7

Oncocytoma. (a) Oncocytoma circumscribed by a thin fibrous capsule. (b) Large oncocytes with vesicular nuclei and often prominent nucleoli. Some cells with smaller, almost pycnotic nuclei. (c) Oncocytes with PTAH positive granules

There is however a number of important differential diagnoses particularly with clear cell oncocytoma. The most important ones include metastatic renal carcinoma, oncocytic mucoepidermoid carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma with clear cell changes, acinic cell carcinoma, oncocytic pleomorphic adenoma, salivary clear cell carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma and oncocytic carcinoma. The oncocytic cells of an oncocytoma, the clear cell variant included, usually stain positive for PTAH which is not the case in any of the differentials apart from oncocytic carcinoma. The latter should be readily distinguished due to cytological atypia which is not present in an oncocytoma. Various amounts of glycogen may be detected with periodic acid-Schiff staining in oncocytes, but mucous stains are negative. This is in contrast to, e.g. mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Oncocytomas are strongly immunoreactive for low molecular weight cytokeratins and CK7, and usually a strong but patchy positivity for CK14, high molecular weight cytokeratins and EMA. Oncocytomas are negative for CD10 and RCC (renal cell carcinoma marker). Vimentin is only weakly and variably positive (Fig. 6.8). The vast majority of salivary gland neoplasms are CK20 negative, but in a series of ten oncocytomas, CK20 immunoreactivity was demonstrated in eight cases [128].

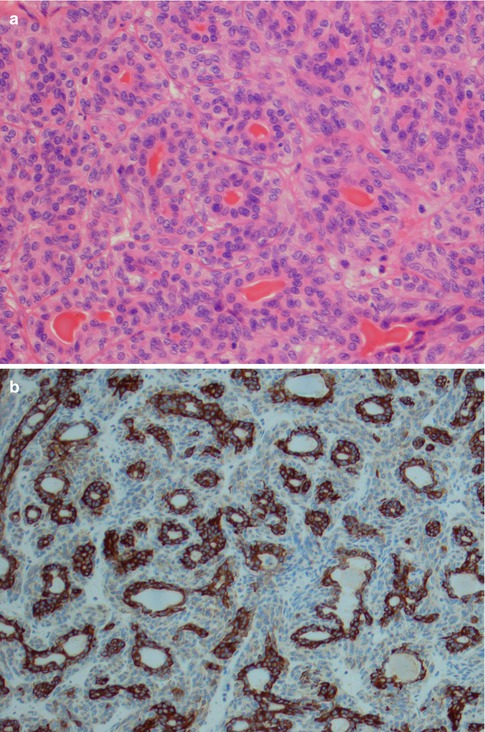

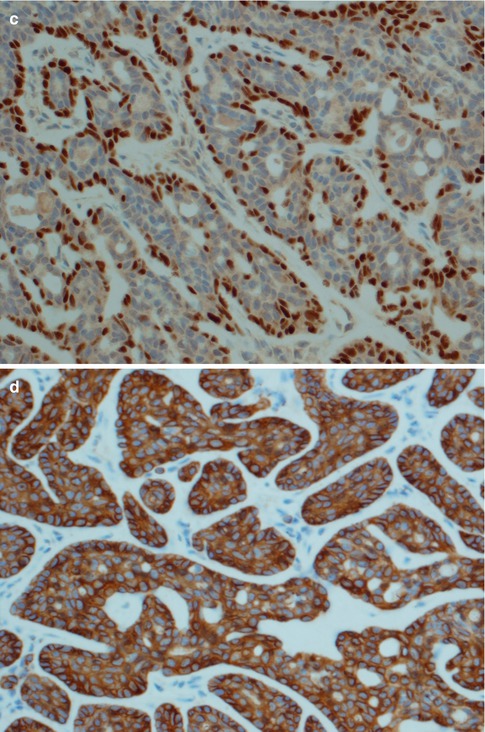

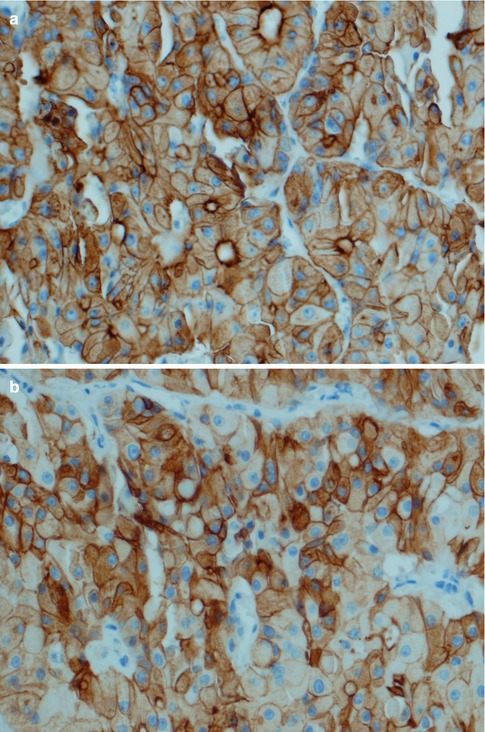

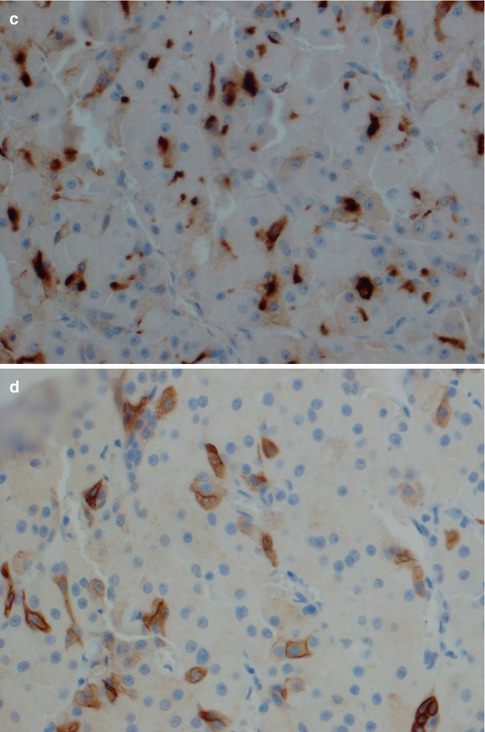

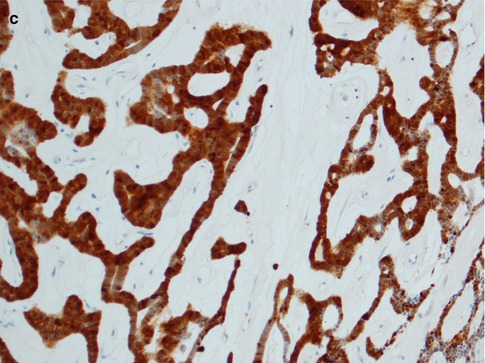

Fig. 6.8

Oncocytoma. (a) Strong cytoplasmic and membranous immunoreactivity for low molecular weight cytokeratin CK8/18. (b) Similar staining pattern with CK7. (c) Strong but patchy positivity for EMA. (d) CK14 shows a similar staining pattern as EMA

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma is typically, but not always, positive for CD10, vimentin and EMA, and variably positive for RCC and CK7. Further, renal cell carcinoma is never positive for p63 [114]. Hence in cases where the tumour cells are positive for CK7 and possibly for CK20 but negative for CD10 and RCC, and only weakly positive or negative for vimentin, the immunoprofile would strongly favour oncocytoma instead of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. The usefulness of mitochondrion-specific antibodies in distinguishing oncocytoma from metastatic renal cell carcinoma has been questioned as renal cell carcinoma can be mitochondria rich [161]. In fact, positive staining with CK14 appears to be rather reliable and perhaps the most useful antibody. In a study of 30 cases of oncocytoma and 33 cases of renal cell carcinoma, all 30 oncocytomas were strongly positive for CK14 positivity, whereas only four renal cell carcinomas showed light and sporadic CK14 immunoreactivity [33]. The study of Jain and associates showed the novel marker AMY1A (amylase α-1A gene) can be of great diagnostic help in the differential diagnosis between oncocytoma and renal cell carcinoma. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (classic and eosinophilic variant) have deletions in the 1p21.1 region that are not present in oncocytomas. Oncocytomas have other deletions on chromosome 1: 1p31.3, 1q25.2 and 1q44. In their study of 75 oncocytomas and 54 renal cell carcinomas, all oncocytomas expressed AMY1A whilst 87 % of renal cell carcinomas were negative [82].

If present, a conventional positive PTAH stain will of course support oncocytoma. In cases of acinic cell carcinoma, the EMA staining tends to be variable from patchy to strong in some cases. Unfortunately acinic cell carcinoma does not have any unique immunoprofile (see Chap. 9) but tend to be positive for some mucins, such as MUC3. Membranous staining for CK18 and positivity for IgA, and to a certain degree PASD positivity, would favour the diagnosis of acinic cell carcinoma instead of oncocytoma. PASD positivity is however also found to a variable extent in oncocytomas. Oncocytomas do not express thyroglobulin or TTF-1 as many metastatic thyroid carcinomas do. Care also has to be taken not to misdiagnose an oncocytic satellite focus in the vicinity of an oncocytoma as a sign of invasion. If an oncocytic neoplasm shows features of chondroid or myxoid metaplasia, spindle or plasmacytoid myoepithelial cell differentiation, or keratin formation, the tumour is best classified as an oncocytic pleomorphic adenoma. Salivary clear cell ‘oncocytic’ carcinomas display cytological atypia that is not present in oncocytomas (see Chap. 15). Oncocytic mucoepidermoid carcinoma only rarely constitutes a differential diagnosis as mucoepidermoid carcinoma frequently is a translocation-associated neoplasm, known to harbour translocations and fusion oncogenes (see Chaps. 7 and 16).

6.3 Canalicular Adenoma

Canalicular adenoma was recognised as a separate entity from other adenomas first in the second WHO classification in 1991. It was defined as ‘a tumour of columnar epithelial cells which are arranged in anastomosing bilayered strands that form a beading pattern. The stroma is loose, highly vascular and not fibrous’ [147]. Although there was not a worldwide recognition in the form of the WHO acceptance before 1991, the canalicular type of adenoma had been widely described for decades before and also its peculiar predilection for the upper lip had been noticed. Canalicular adenoma was described as early as 1928 by Eggers [44] and in several reports in the 1950s [15, 16]. Canalicular adenoma was not included as a separate entity in the first WHO classification in 1972 [159] but was during the 1970s recognised by many authors as a separate entity [29, 125, 171]. In the early 1980s, Gardner and Daley clearly voiced the opinion that canalicular adenoma is not a basal cell adenoma but a separate entity and a wider acceptance was eventually obtained leading to the inclusion in the second WHO classification in 1991 [34, 54, 165].

Canalicular adenoma is one of the more common adenomas, but as with all salivary gland tumours, there is a wide variation from institute to institute, from country to country, etc. Large recent studies from three different countries (the UK, the USA and China) reported a wide range and canalicular adenoma represented 0–12 % of all benign tumours. The UK study by Jones et al. comprised 741 benign and malignant salivary gland tumours and canalicular adenoma constituted 7.3 % of all benign tumours (4.7 % of all tumours, benign and malignant). Only pleomorphic adenoma (68.4 % of all benign tumours) and basal cell adenoma (7.7 %) were more common. The rather low incidence of Warthin tumour in their study (7.1 %) is likely explained by that for a substantial part of the study the material derived from a practice with predominantly minor salivary gland in origin [83]. The study from Northern California reported by Buchner et al. comprised 380 salivary gland tumours from one institute, and of the 224 benign tumours, canalicular adenoma (10 %) was the third most common benign tumour after pleomorphic adenoma (67 %) and cystadenoma (11 %). Also this material primarily derived from an oral and maxillofacial pathology laboratory and hence there was a low number of major salivary gland Warthin tumours [25]. Similarly, Yih and associates in Portland, USA, reviewed 213 intraoral minor salivary gland tumours, and canalicular adenoma was the second most common benign tumour (after PA) representing 25 of 119 benign tumours [175]. In contrast, in the study of 737 intraoral minor salivary gland tumours by Wang and associates, there was not a single case of canalicular adenoma. They also referred to several other Chinese studies, all of which had not revealed any canalicular adenoma [167]. This apparent geographical and/or racial difference was also supported by the AFIP study by Auclair et al. where no canalicular adenoma at all appeared in their Asian population [8]. In a non-Asian population, it thus appears that canalicular adenoma is the second most common benign minor salivary gland tumour after pleomorphic adenoma representing between 6.9 and 21 % of the benign tumours (Table 6.2).

Canalicular adenomas occur almost exclusively in patients over 50 years of age and are localised to the upper lip in approximately 90 % of cases. The vast majority of the remaining 10 % of cases are located in the buccal mucosa [25, 83, 147, 167]. They may be found in the oropharynx and even in the oesophagus [61], and a few cases of intra-mandibular canalicular adenoma have been reported [38]. They present as a slowly growing painless nodule and hence usually in the upper lip. As they may fluctuate in size, they are sometimes mistaken clinically for a mucocele. Unlike membranous basal cell adenoma, there is no known association with dermal cylindroma. Canalicular adenoma is not uncommonly multifocal in the upper lip, and also cases of multiple canalicular adenomas involving the upper lip and the buccal mucosa have been reported [105, 125, 126, 140, 153, 176]. Canalicular adenoma has a low tendency to recur but may recur sometimes after months and then with multiple recurrences, and sometimes first after many years [68, 88]. Some of the recurrences may indeed have been manifestation of its well-known multicentric growth pattern. Malignancy is not known to develop.

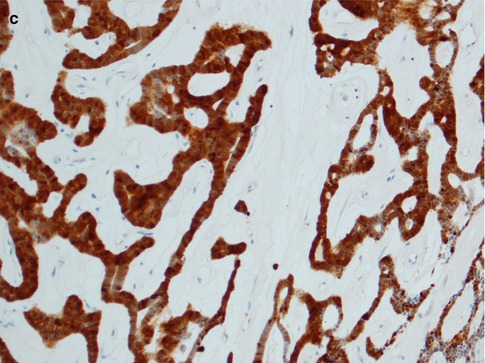

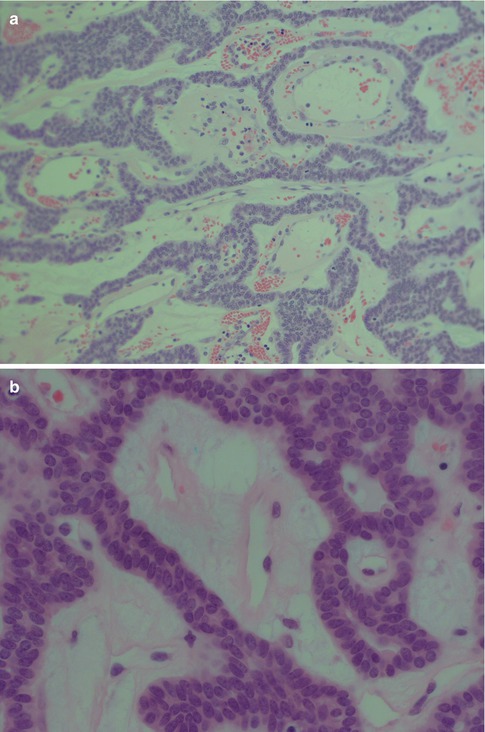

The histology is characteristic, and canalicular adenoma is readily diagnosed in the majority of cases and will only rarely be confused with a basal cell adenoma, or possibly with adenoid cystic carcinoma. Canalicular adenomas are relatively small, rarely larger than 2 cm, and are grossly well circumscribed. Microscopically they are seen to be circumscribed, but some of the larger may be encapsulated. The most distinguishing microscopic feature is likely the very paucicellular stroma that is not fibrous but characteristically very highly vascularised. The epithelial cells are primarily columnar, but some are cuboidal containing a weak eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei are regular and round or oval and rarely show vesicles. The cells are typically arranged in beaded anastomosing, often bilayered strands and cords. These strands of columnar cells are situated opposite to each other and alternatively widely separated. This arrangement leads to the appearance of narrow channels, i.e. canaliculi (Fig. 6.9). Canalicular adenoma consists of only one columnar ductal cell type contrary to all basal cell adenoma variants that exhibit some degree of myoepithelial cell participation in addition to ductal cells [177]. A recent study suggests the cell of origin to have features of both the intercalated duct cells and the striated duct luminal epithelial cells [74]. The immunoprofile indicates an excretory duct origin with cells positive for AE1/AE3, several cytokeratins and S-100. The tumour cells are negative for CEA and only infrequently positive for EMA, and negative for p63 and calponin [43, 49, 134]. The lack of SMA and p63 positive cells surrounding ductal cells hence differentiate canalicular adenoma from a basal cell adenoma of trabecular type, as does the strong and frequent staining for S-100 protein represents an enigmatic characteristic of canalicular adenoma.

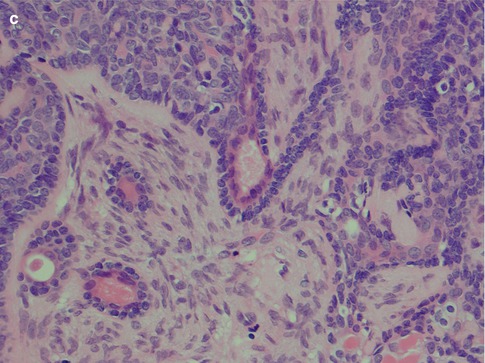

Fig. 6.9

(a) Canalicular adenoma with anastomosing strands of epithelial cells in a loose, highly vascular stroma. (b) Columnar regular cells forming bilayered strands. (c) Uniform positivity for S-100

6.4 Sebaceous Adenoma

Since the report by Hamperl in 1931, it has become well recognised that sebaceous glands and sebaceous metaplasia are frequent findings in salivary glands [66]. Sebaceous adenoma, on the other hand, is a very rare tumour with probably less than 30 cases reported in the English literature thus comprising well less than 0.5 % of the salivary adenomas. It is a well-circumscribed or encapsulated tumour with half of the reported cases arising in the parotid gland. With decreasing frequency sebaceous adenoma is also found in the buccal mucosa, retromolar region and the submandibular glands [56, 57, 59]. Although salivary sebaceous adenoma was recognised already in the 1960s [4, 35], there are very few series published apart from the studies by Gnepp in the 1980s, and most publications have been case reports [13, 40, 80, 149].

The interested reader is warmly recommended to take part of Gnepp’s journey into the world of sebaceous salivary neoplasms, published in 2012. He described five types of salivary gland sebaceous tumours: sebaceous adenoma, sebaceous lymphadenoma, sebaceous carcinoma, sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma and sebaceous differentiation in other types of salivary gland lesions [58]. Sebaceous adenoma is usually a well-circumscribed, often encapsulated lesion. The adenoma consists of irregular nests of sebaceous cells without cellular atypia. These nests vary in size and shape and may be embedded in a fibrous stroma (Fig. 6.10). There are areas with squamous differentiation and the tumours are often cystic. The epidermoid cells have no or minimal atypia [57, 147].

Fig. 6.10

Parotid sebaceous adenoma with solid nests of sebaceous tumour cells

Sebaceous lymphadenoma is a distinct variant of sebaceous adenoma ‘with groups of well differentiated sebaceous cells arranged in a glandular configuration with associated ducts of variable size, lying in a stroma of lymphocytes, with or without follicles’ [147]. Although sebaceous lymphadenoma is more common than lymphadenoma, it is still a rare condition. The name sebaceous lymphadenoma was first used in 1960 when McGavran and associates described two parotid cases [113]. Since then only approximately 60 cases have been reported in the literature, 22 of which in the series reported by Seethala and associates in 2012 [50, 59, 69, 107, 110, 144, 145, 169]. The sebaceous lymphadenoma described by Fleming and Morrice was apparently in a lymph node described with capsule and sinuses [51]. The vast majority of cases have been parotid lesions, but at least five occasions the tumour has been extraparotid [95, 111, 132, 145]. Three of the reported cases of sebaceous lymphadenoma have been unilocular and cystic [27, 115, 129]. One may argue that a unilocular cystic sebaceous lymphadenoma perhaps merely represents a lymphoepithelial cyst with sebaceous differentiation.

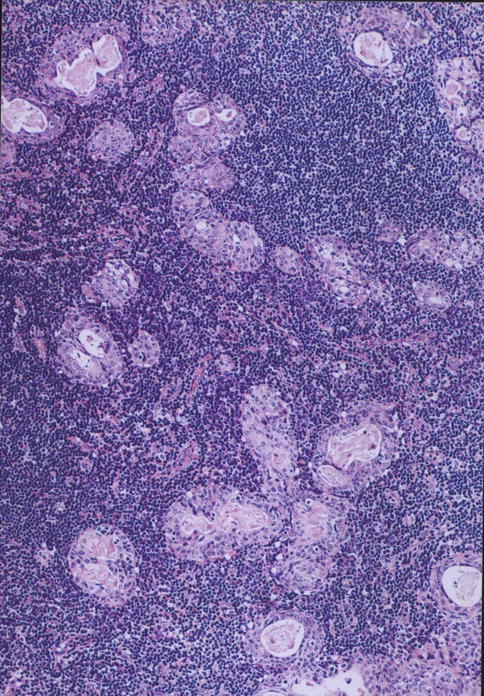

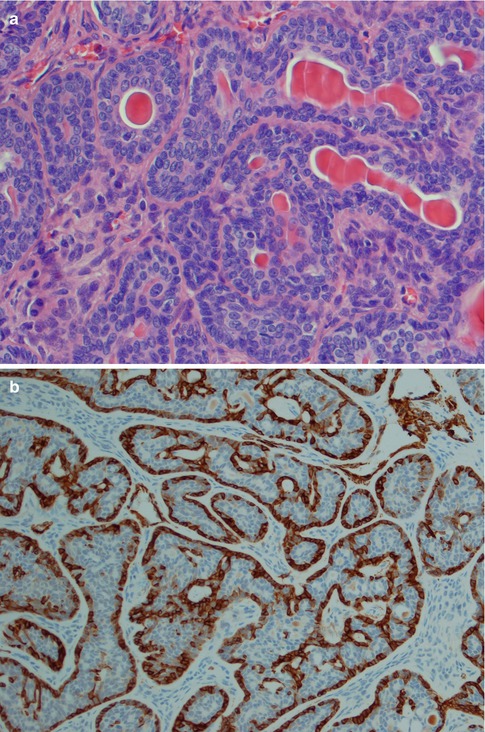

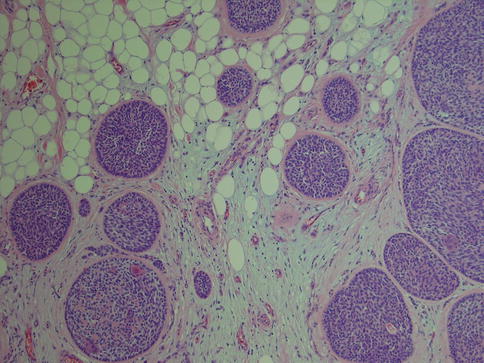

6.5 Lymphadenoma

Lymphadenoma (non-sebaceous lymphadenoma, lymphadenoma without sebaceous differentiation) is an adenoma accompanied by a dense lymphoid infiltrate. This is a recently recognised salivary gland adenoma that probably is not a distinctive tumour entity but representing an adenoma (basal cell adenoma or cystadenoma) accompanied by a heavy (reactive?) lymphoid infiltrate. The importance of its recognition lies in that it can be misdiagnosed as lymphoepithelial carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma in a lymph node or lymphoepithelial sialadenitis.

Some cases of cystic adenoma with prominent lymphoid component were first described by Auclair et al. in 1991 and named cystic lymphadenoma [8]. In a review paper a couple of years later, Auclair introduced the term lymphadenoma [7]. Until recently, very few cases (10–15) had been described and most as case reports [20, 28, 36, 97, 104, 121, 173]. All those reported cases of lymphadenoma have been parotid lesions. During the last 2 years two larger studies have been performed, together identifying another 20 cases of lymphadenoma, all but four were parotid lesions [145, 168]. One atypical case of parotid lymphadenoma with serous acinic cell differentiation has recently been described [79].

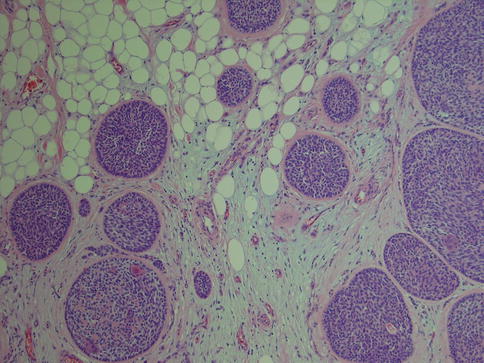

Lymphadenoma comprises intimately admixed adenomatous and lymphoid components in variable proportions. Lymphadenoma is generally well circumscribed, a feature that distinguishes it from lymphoepithelial sialadenitis. The epithelial proliferation is also more pronounced than that seen in lymphoepithelial sialadenitis (see Chap. 2). The epithelial component varies from anastomosing trabeculae, islands and tubules to cystically dilated glands filled with proteinaceous materials. The lymphoid component can be with or without lymphoid follicles and consists of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The solid epithelial island and trabeculae are composed of basaloid cells, whilst the cyst or gland-lining cells are ductal (Fig. 6.11) [31]. Although one immunohistochemical study did not confirm the presence of myoepithelial cells [173], another recent study demonstrated the presence of both luminal and myoepithelial cells [36]. Some may have argued that lymphadenoma may represent an adenoma arising from heterotopic salivary tissue in an intra- or periparotid lymph nodes. Hilus structure with salivary inclusions or D2-40 (podoplanin)-positive marginal sinus was identified in four and nine of their nine cases, respectively [168]. On the other hand, others have not demonstrated recognisable lymph node structures with sinuses, and furthermore, the lymphoid component is by many considered to represent tumour-associated lymphoid proliferation [7, 41].