Chapter 30 Osteoporosis

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common skeletal condition that results in significant morbidity and mortality for men and women, with ever increasing health care costs.1 Osteoporosis afflicts 75 million people in the US, Europe and Japan and results in more than 1.3 million fractures annually in the US alone.1

In Australia, 1 in 2 women and 1 in 3 men over the age of 60 develop this disease. It is estimated that approximately 2 million Australians have osteoporosis, and this figure is expected to rise to 3 million by 2021.1 It is predicted that by 2021, 1 in 3 hospital beds in Australia will be occupied by a woman with an osteoporotic fracture. Hip fracture is a serious consequence of osteoporosis.

Risk factors

There are numerous risk factors for osteoporosis, but only those related to lifestyle behavioural factors will be discussed.2 The most important risk factors are:

Genetics

Although genes play a part in determining the risk of osteoporosis, the genetic contribution is not well understood. Two recent studies have reported gene variants associated with osteoporosis.3,4 It is estimated that genes account for 25–45% of variation in a 5-year change in bone mineral density (BMD) in women and men.5

However, prospective 25-year follow up of a nationwide cohort of elderly Finnish twins has concluded that susceptibility to osteoporotic fractures in elderly Finns is not strongly influenced by genetic factors, especially in elderly women.6

Gender/hormones/ageing

It is estimated that 30% of 50-year-old women already have osteoporosis.7 At age 65 years, 50% of women and 20% of men already have osteoporosis, and by age 75 years, 70% of men and women will have osteoporosis.7 Women are reported to usually lose approximately 1–2% of cortical bone per year after the age of 40–50 years. Moreover, 3–7 times more bone is lost in the first 7–10 years after becoming menopausal.8

In men, osteoporosis begins 5–10 years later than in women.9 Approximately 25% of men older than age 60 years will have an osteoporotic hip fracture. Mortality from fracture is higher in men.9

Using fracture as the benchmark for the risk of osteoporosis, risk for men in their lifetime is 13–25%, as compared to 50% in women.10 Bone loss is increased by oestrogen or testosterone deficiency from any cause at any time.11, 12

Moreover, a recent literature review shows that the most successful and essential strategy for improving BMD in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is to increase caloric intake such that body mass is increased and there is a resumption of menses.13 However, the study also pointed out that further long-term studies to determine the persistence of this effect and to determine the size of this effect and other strategies on fracture risk are indeed warranted.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle risk factors for osteoporosis can impact growing bones in-utero resulting from maternal lifestyle and in early childhood. Epidemiological studies suggest there is a relationship of osteoporosis with birth weight, weight in infancy, hereditary, gender, diet, physical activity, sun exposure, endocrine status and smoking. Infants born to mothers who are vitamin D deficient are at risk of abnormal bone formation.14

The Mediterranean Osteoporosis Study has concluded that in both men and women lifestyle is important for bone health, and that there are a number of identifiable factors that can reverse the risk for osteoporosis.15,16

In men, the potentially reversible risk factors included low Body Mass Index (BMI), reduced physical activity, low exposure to sunlight, and low consumption of tea and alcohol and increased use of tobacco remained independent risk factors for 54% of hip fractures.15

In women, significant risk factors identified included low BMI, short fertile period, low physical activity, lack of sunlight exposure, low milk consumption, no consumption of tea, and a poor mental score.14 No significant adverse effects for coffee or smoking were reported. Moderate consumption of spirits was a protective factor in young adulthood, with no other risk effects observed for overall alcohol consumption. A low BMI and milk consumption were significant risks only in the lowest 50% and 10% of the population, respectively. A late menarche, poor mental score, low BMI and physical activity, low exposure to sunlight, and a low consumption of calcium and tea remained independent risk factors, accounting for 70% of hip fractures.14 Hence, approximately 50% of the hip fractures could be explained on the basis of potentially reversible risk factors. However, it should be noted that the use of risk factors to predict the occurrence of hip fractures had only a moderate sensitivity and specificity.

Recently, a study reported the 5-year risk of fracture among post-menopausal women of various ethnic backgrounds. The algorithm of 11 clinical factors included age, health status, weight, height, race/ethnicity, self-reported physical activity, history of fracture after age 54 years, parental hip fracture, current smoking, current corticosteroid use, and treated diabetes.17

Mind–body medicine

Stress and/or depression

There have been numerous reports that have investigated the association between depression and BMD. An early study has reported that women with depression have much lower BMD, and higher cortisol levels than controls.18 A recent review has concluded, however, that while most studies support the data that depression is associated with an increased risk for both low BMD and fractures, variations in study design, sample compositions, and exposure measurements have made the causative role played by depression in osteoporosis difficult to conclude.19

Sunlight

Sunshine is the main source of vitamin D produced by the body in response to direct skin exposure to UVB. This means that no or minimal exposure to sun can contribute to vitamin D deficiency, with risk factors including: dress codes (e.g. wearing veils, migrants, infants of migrant families); dark skin colour; living in geographically prone areas, especially over winter (southern or northern latitude); institutionalisation; elderly; being bed-bound; intellectual disability; prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding; restricted sun exposure, and certain medical conditions.20, 21 A study of 250 institutionalised patients following stroke demonstrated that regular sun exposure over 1 year increased vitamin D levels fourfold accompanied with a 3% increase in BMD, compared with the control group involving standard hospital care.22

Other than osteoporosis, osteomalacia and rickets, lack of sun exposure and vitamin D deficiency have been linked to many serious chronic diseases, including autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, multiple sclerosis, depression, risk of infections, skin diseases, numerous cancers and diabetes.23–47

A recent review has proposed that sensible sun exposure can raise blood levels of 25(OH)D >30 ng/ml.48 Vitamin D deficiency is the most significant contributor to osteoporosis, fractures and falls and is a major public health issue in some parts of the world. Supplementation of Vitamin D in the form of cholecalciferol is necessary to establish normal blood levels.49

Environment

Smoking

Smoking is a risk factor for osteoporosis. A meta-analysis of the literature demonstrates an association of BMD and increased lifetime risk of vertebral fractures by 13% in women and by 32% in men, and hip fracture 31% in women and 40% in men.50 The effects were greatest in men and in the elderly, and were dose-dependent. BMD continued to significantly reduce over the time of continued smoking. Moreover, in an antioxidant vitamin supplement study it was reported that smoking had adverse effects on the skeleton.51

Physical activity/exercise

A Cochrane review has found that exercise is beneficial in the treatment of osteoporosis.51 This benefit is demonstrated in all age groups, including post-menopausal women.52, 53, 54 BMD can be improved by walking, weight-bearing and resistance exercises.17, 55 It has also been reported that resistance and weight-bearing exercises can also improve muscle strength which can help reduce falls and osteoporotic fractures.56, 57

High intensity training

A recent review has reported that several studies with post-menopausal women demonstrate modest increases in bone mineral toward the normal that are observed in a healthy population in response to high-intensity training.58 Physical activity continues to stimulate bone diameter increases throughout the lifespan. Therefore, these exercise-stimulated increases in bone diameter significantly decrease the risk of fractures by mechanically counteracting the thinning of bones and the increasing bone porosity and fragility.17

Vigorous walking

A recent study that investigated walking intensity in post-menopausal women demonstrated that exercise intensities about 115% of ventilator threshold or 74% of VO2 max, or at walking speeds greater than 6.14 km/hr mechanical loading of 1.22 times their body weight was sufficient for increases in leg muscle mass and preservation of BMD in these post-menopausal women.59 The study demonstrates vigorous speedy walking, not gentle amble walking, as helping to maintain BMD.

Athletic training

Moreover, young women who exercise athletically have higher bone mass than their sedentary counterparts, and this difference may be sustained in adulthood.60 Hence, moderate physical activity during the years of peak bone acquisition may have lasting benefits for lumbar spine and proximal femoral BMD in post-menopausal women.17

Nutritional influences

Diets

The metabolism associated with bone and muscle strength, and in particular for bone formation, requires calcium and phosphorus plus vitamins D, C, B and K, as well as the minerals boron, zinc, iron, fluoride, copper, magnesium, manganese, selenium, iodine, silicon and chromium.62, 63

Any disease that causes malabsorption of any of these nutrients can impact on BMD. For instance, a study of young children with coeliac disease, demonstrated improved BMD after 4 years on a strict gluten-free diet.64

Dairy intake

Of interest, a meta-analysis of 47 studies found little relationship between dietary calcium intake in childhood and bone health.65 The review examined 37 studies that found no relationship between dairy or dietary calcium intake and measures of bone health. Only 9 studies demonstrated small positive effects on bone health from dairy foods, although 3 were confounded with milk-fortified vitamin D. These studies suggest vitamin D from safe sunshine exposure or supplementation may be the more significant source than dietary dairy intake alone. Also the study implies that once minimum calcium needs are met, extra calcium from dairy source is not required.

Caloric restriction and weight loss diets

Caloric restriction and weight loss diets may actually significantly reduce BMD according to a weight loss study of 50–60 year-old adults (BMI 23.5–29.9) which also demonstrated that the exercise group had no loss of BMD compared with control group.66

Western diets high in animal protein

An early study has reported that Western diets that consist of high levels of animal protein are acidic in character, and can lead to an acidic diet which then is believed to release alkaline salts of calcium from bone.67

A reduction in animal protein consumption has been proposed to decrease bone resorption and affect calcium balance in a favourable way. A high vegetable to animal ratio, with high dietary calcium intake, appears to protect against osteoporosis.68

Many factors are known to influence bone health. Protein can be both detrimental and beneficial to bone health and this depends on a variety of factors that include the amount of protein consumed in the diet, protein source, calcium intake, weight loss, and the acid/base balance of the overall diet.69

Alkaline diets

The notion that diets rich in vegetables, fruits and whole grains are more alkaline, and hence provide protection for bone health has not been supported by a recent randomised control trial (RCT).70 The RCT of menopausal women has demonstrated that supplementation with a potassium citrate supplement over 2 years did not reduce bone turnover or increase BMD in healthy post-menopausal women. The results suggest that alkali provision does not explain any long-term benefit of fruit and vegetable intake on bone health.

Raw food vegetarian diet

A further study with participants consuming a long-term raw food vegetarian diet has concluded that this diet was associated with low bone mass at clinically important skeletal regions and was without evidence of increased bone turnover or impaired vitamin D status.71

Mediterranean diet

In Europe, there is a noticeable difference in the severity of osteoporosis, the lowest incidence being reported in the Mediterranean area.72 The beneficial effect has been attributed mainly to a specific eating pattern. The Mediterranean diet has numerous food items that contain a complex array of naturally occurring bioactive molecules with anti-inflammatory and alkalinising properties that together may contribute to the bone-sparing effect that has been documented.70

DASH diet

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), which is a diet rich in fruit and vegetables, has also been reported to reduce bone loss.73 Moreover, the DASH diet has been demonstrated to reduce hypertension and has subsequently been shown to reduce coronary artery disease and stroke risk.

Tea

Older women who drink tea have a reported higher BMD than those who do not drink tea.74 A Taiwanese study of 1037 people aged 30 years or more, found that those who drink green, black or oolong tea regularly over a decade have a higher BMD than those who drank tea occasionally.75 A recent epidemiological study from the Middle East reported that habitual tea drinking did not impact on bone health, rather that multi-factorial factors (high education levels, being overweight, and being treated for HT) had positive effects on BMD in this population.76

However, a study that assessed risk factors for osteoporosis in Iranian women compared with Indian women has concluded that high habitual tea consumption (4–7 cups per day) was protective in both of these populations.77

A study of impaired hip structure, assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry areal BMD, which is an independent predictor for osteoporotic hip fracture, concluded that tea drinking was associated with preservation of hip structure in elderly women.78 This study provides further evidence for the beneficial effects of daily tea consumption on the skeleton. Flavonoids in tea are thought to be responsible for their protective effects against the development of osteoporosis.79

Soft drinks

Five to 6 servings per week of soft drinks, particularly cola, are recognised as a risk factor and linked to low BMD according to a population study of over 2500 adults.80

Soy and soy isoflavones

A number of observational studies have suggested that populations with a high dietary soy intake have a lower incidence of osteoporosis and related fractures when compared to Western populations.81

Soy contains protein and also isoflavones (phytoestrogens), and has been reported to increase BMD.82 The phytoestrogens have an affinity for oestrogen receptors and can behave similar to endogenous oestrogens. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials has shown that soy isoflavone intake inhibits bone resorption and can stimulate bone formation in menopausal women.83 However, a recent RCT has reported that in apparently healthy early post-menopausal white European women the daily consumption of foods containing 110mg of soy isoflavone aglycone equivalents for 1 year did not prevent post-menopausal bone loss and did not affect bone turnover.84

Phytoestrogens act on both osteoblasts and osteoclasts through genomic and non-genomic pathways as evidenced through in vitro and in vivo studies.85 Given that epidemiological studies and clinical trials suggest that soy isoflavones have beneficial effects on bone mineral density, bone turnover markers, and bone mechanical strength in post-menopausal women, the conflicting results make conclusions difficult to gauge. Differences in study design, oestrogen status of the body, metabolism of isoflavones among individuals in different population groups, and other dietary factors advocate that long-term safety and efficacy of soy isoflavone supplements in the prevention of osteoporosis remains to be demonstrated.

Dietary and supplemental omega-3 fatty acids (FAs)

An imbalance of omega-3 to omega-6 FAs is associated with lower BMD at the hip in both men and women.86 Also an early study has reported that dietary omega-3 FAs can suppress production of osteoclast-activation.87

A small placebo-controlled trial using a combination of evening primrose oil and fish oil supplementation over a 3-year period increased spinal BMD.88

Reviews report that the available evidence demonstrates that increased daily intake of dietary n-3 FAs decreases the severity of autoimmune disorders, lessens the chance of developing cardiovascular disease, and protects against bone loss during post-menopause.89

A recent systematic review concludes that even though studies support the beneficial effects of n-3 FAs on bone health and osteoporosis, the dissimilar lipid metabolism in humans and animals, the various study designs, and controversies over the human clinical study outcomes make definite conclusions as to the efficacy of n-3 FAs in preventing osteoporosis difficult to interpret.90

Nutritional supplements

Vitamins

Vitamin D

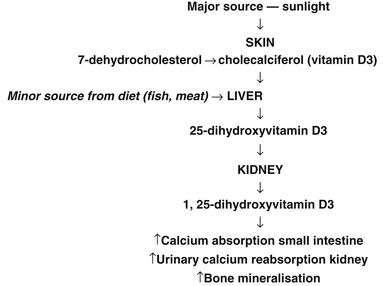

Vitamin D has a pivotal role in bone metabolism, it controls intestinal calcium absorption plus its deposition into bone.91 The main source of vitamin D is sunlight exposure (see Figure 30.1).92 Ninety percent of vitamin D is produced in the skin from sunshine exposure (UVB) with only 10% from dietary sources. Dietary sources include fatty fish (e.g. mackerel), cod-liver oil, sun-exposed mushrooms and liver. The majority of women with osteoporosis have vitamin D deficiency and resulting bone loss.93 The Geelong vitamin D study on post-menopausal women found that the majority of the participants were vitamin D deficient during winter.94

Figure 30.1 Major sources of sunlight

(Source: adapted from Nowson CA, Diamond TH, Psco JA, et al. Australian Family Physician. 2004;33(3):133–8)

Vitamin D deficiency is likely to be the commonest nutritional deficiency in Australia and many other countries, and may well be the most important one.95–100 As mentioned previously, risk factors for vitamin D deficiency include dark skin colour, dress codes (e.g. wearing veils, migrants, infants of migrant families), living in geographically prone areas especially over winter (southern or northern latitude), institutionalisation, being bed-bound, intellectual disability, elderly, prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding, restricted sun exposure, and certain medical conditions. Vitamin D deficiency has re-emerged as a major public health issue affecting at-risk groups such as the elderly, but also infants and young children potentially causing hypocalcemia, seizures, rickets, limb pain, tooth loss and poor dentition and risk of fracture.101–107 Breastfed infants of mothers who were vitamin D deficient during pregnancy were at high risk of vitamin D deficiency.108

Vitamin D has a multiplicity of roles involving virtually every body system.

Improved Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

A large RCT of elderly people over a 5-year period demonstrated vitamin D combined with calcium supplementation has long-term benefit on BMD compared with calcium alone or control group, particularly in subjects with sub-optimal vitamin D levels.109 Moreover, it is well documented that throughout the lifecycle the skeleton requires optimum development and maintenance of its integrity to prevent fracture. The data is promising for the use of combined calcium with vitamin D and the use of vitamin K.110

Reduction of fractures

A meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies found that vitamin D supplementation prevented hip and non-vertebral fractures in the elderly.111 Of interest, in a study of osteoporotic women over 65 years of age with a history of previous hip fractures, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, up to 1 year, increased BMD, corrected secondary hyperparathyroidism, increased urinary excretion but did not reduce the risk of further fractures.112

Muscle strength and prevention of falls

Vitamin D3 supplementation can improve muscular strength and balance, which can help prevent falls and consequently fractures.113,114 An Australian study that assessed the role of vitamin D on muscle strength in patients with previous fractures reported that muscle strength was most strongly associated with serum 25 hydroxy-vitamin D levels of >50 nmol/L.115 The study concluded that there was a significant association between serum 25 hydroxy-vitamin D levels and left leg muscle strength. This association may also have benefits for BMD.

Reduction of pain

In a recent UK study that investigated the use of vitamin D and chronic widespread pain in a white middle-aged British population, it was reported that the current vitamin D status of the study population was associated with chronic widespread pain in women but not in men.116 Follow-up studies were cited as needed to evaluate whether higher vitamin D intake could abrogate chronic widespread pain.

Traditionally, vitamin D3 is preferred over vitamin D2 which has a much shorter half-life than D3, and is also about one-third as potent. However, more recent research suggests that vitamin D2 is equally effective to vitamin D3 according to a double-blind randomised study of 68 healthy adults.117 The subjects received either vitamin D2 (1000IU), vitamin D3 (1000IU), a combination of D2 plus D3 (500IU) or placebo over an 11-week period, in winter, which demonstrated mean blood levels significantly increased from baseline by 9ng/ml without any differences between groups and with no change in placebo. These findings suggest vitamin D2 and D3 supplements are equally effective in raising serum levels. Similarly a 6-week study of young children with hypovitaminosis D demonstrated equivalent outcomes in improved serum 25(OH)D3 concentration levels from supplementation with elemental calcium (50mg/kg/day) combined with either vitamin D2 (2000IU) daily, vitamin D2 (50 000IU) weekly, or vitamin D3 (2000IU) daily.118

Researchers found that a single high dose of vitamin D3 (100,000IU) every 3 months can also achieve normal serum levels in vitamin D deficient aged care residents without risks of side-effects.119

However, a recent study in JAMA shows a yearly oral dose of 500 000IU of cholecalciferol (alone) in elderly increased the risk of falls and fractures.120

If it is possible to increase sunlight exposure, then the dosage of oral vitamin D can be reduced. It is better to have the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the upper half of the usual range because of the vital importance of this nutrient.

Vitamin K

Vitamin K is essential for the activation of osteocalcin which is synthesised by osteoblasts, and it is important in reducing fracture risks and maintaining bone mineral density. Patients with osteopenia and fracture have significantly decreased levels of vitamin K. This fat-soluble vitamin comes in 2 forms, vitamin K1 and K2. Vitamin K1 is found in green leafy vegetables, whereas vitamin K2 is found in meat and fermented products such as natto (fermented soybeans) and cheese.122, 123

In a systematic and meta-analysis of RCTs investigating the efficacy of vitamin K in the prevention of fractures it was suggested that supplementation with vitamin K phytonadione (vitamin K1) and menaquinone-4 (vitamin K2) reduced bone loss and fracture incidence (up to 80% reduction in hip fractures).124 In the case of menaquinone-4, there was a strong effect on incident fractures among Japanese patients.

A prospective randomised clinical study in osteoporotic patients using vitamin K2 found that it could maintain lumbar bone mineral density.125 When given together with vitamin D3 it has an additive effect in reducing post-menopausal bone loss.126 Another study over a 2-year period also demonstrated a synergistic effect of vitamin D3, calcium with vitamin K1 on BMD in 60-year-old healthy non-osteoporotic women.127 Moreover, it has been recently proposed that there is an important role for vitamin K2 when used in combination with bisphosphonates or raloxifene in the prevention of fractures in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis with vitamin K deficiency.128

A recent RCT that employed a daily dose of 5mg of vitamin K1 supplementation for 2 to 4 years did not protect against age-related decline in BMD.129 However, it was also documented that it may protect against fractures and cancers in post-menopausal women with osteopenia.

Vitamin C

A prospective study in a group of smokers with insufficient intake of vitamins C and E increased the risk of hip fracture, whereas a more adequate intake was protective.51

A recent study with high dose vitamin C has reported that it was associated with a better BMD and a lower 4-year bone loss in elderly men.130 The total amount of vitamin C ingested (dietary + supplemental) was approximately 223mg/day.

Suggested dosages: 500–1000mcg calcium ascorbate, twice daily.

Folate and B group vitamins

Elevated homocysteine levels have been linked to osteoporosis.131,132 Folic acid, vitamin B6 and B12 can reduce homocysteine levels, and hence may have a role to play in maintaining bone health.133,134 A Japanese study of 628 stroke patients (>65 years of age) with high baseline levels of homocysteine and lower levels of serum vitamin B12 compared with a healthy reference range were supplemented with folate (5mg/day) plus mecobalamin (vitamin B12 1500mg/day) or placebo.135 After 2 years, the placebo group had significantly more hip fractures than the vitamin treatment group, BMD had not changed in both groups but, as expected, was significantly lower in the hemiplegic side for both groups. More studies are required.

Vitamin A

According to the Rancho Bernardo Study, Vitamin A above the recommended daily intake (2000–2800IU/day) is a significant risk factor for reducing bone mass in the elderly, who are at greater risk of vitamin A toxicity.136 The BMD further reduced as the intake of vitamin A increased beyond this level. The authors recommended avoiding vitamin A above recommended daily intake levels in the elderly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree