![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Utilize the current osteoporosis clinical guidelines to differentiate normal bone health, osteoporosis, and osteopenia.

2. Evaluate benefits and barriers of available bone densitometry devices and methods.

3. Develop osteoporosis screening services within a community pharmacy practice setting including marketing, primary care provider collaboration, and follow-up.

4. Recommend patient-specific over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription medication treatment regimens and lifestyle modifications.

BACKGROUND

BACKGROUND

Osteoporosis is a silent disease that is characterized by low bone mass, deterioration of bone architecture, and increase risk of fracture. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), osteoporosis is estimated to be a major health threat for Americans with 55% of people 50 years and older at risk.1 Of the 43 million people at risk, 10 million have osteoporosis while the other 33 million suffer from low bone density of the hip, putting them at increased risk of osteoporosis.1

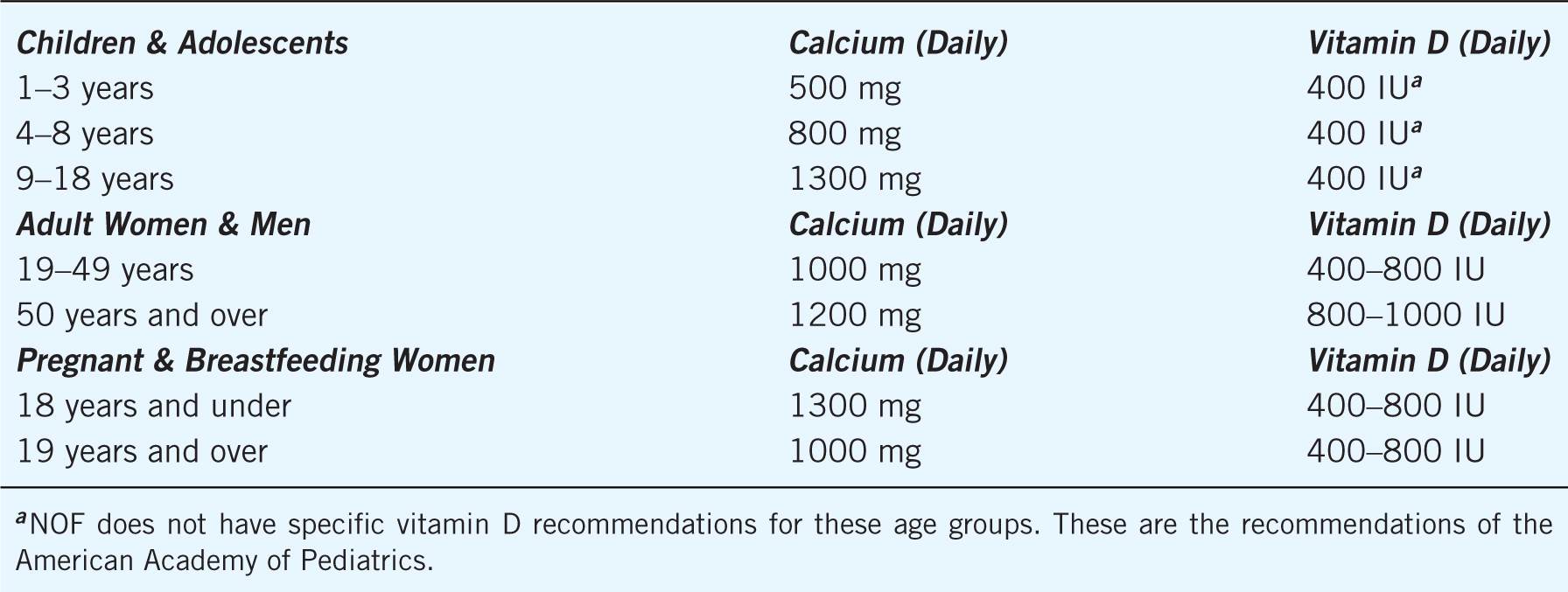

Osteoporosis exerts a large financial burden on the health system. In 2005, it was estimated that osteoporosis-related complications (such as fractures) cost an imposing $17 billion in the United States. With the aging population, this financial burden is expected to double or triple by the year 2040.1 Not only is osteoporosis a costly disease, it is also a debilitating disease. Over 430,000 hospital admissions, 2.5 million physician visits, and 180,000 nursing home admissions each year can be attributed to fractures from osteoporosis.2 Hip fractures are among the most common and debilitating of osteoporosis-related complications.3 It is estimated that 50% of Caucasian women will experience a fracture related to osteoporosis at some point in their lifetime.4 As a result of osteoporosis-related fractures, patients may experience a decreased quality of life because of acute and chronic back pain, disability, limited mobility, and loss of height that can all be deleterious results of a fracture.5 Table 13–1 details nonmodifiable and modifiable risk factors for osteoporosis.

Table 13–1. Risk Factors for Osteoporosis

Currently the NOF, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), and International Society of Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) recommend bone mineral density (BMD) screening for all women aged 65 and greater regardless of risk factors, all postmenopausal women with a fracture, postmenopausal women younger than 65 years with one or more risk factors (other than fracture or low sex hormones), and any women who are considering therapy for osteoporosis.1,6–8 The AACE also recommends testing women with increased risk factors for fractures.6,7 In addition, ISCD recommends testing women with a disease or taking a medication associated with low bone mass or bone loss.8 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends routine screening beginning at age 60 for women at increased risk of fracture, and it makes no recommendations for or against routine osteoporosis screening in post-menopausal women who are younger than 60 years or who are not at increased fracture risk.9

Pharmacists have the opportunity to play an important role in increasing awareness of bone health and performing osteoporosis screenings. In the community setting, pharmacists are accessible to patients, have an established presence in the community, and have a direct relationship with patients and primary care providers, which provide an optimal setting for osteoporosis screenings.2 In addition to patient-specific recommendations on prescription and OTC medications, pharmacists can encourage dietary changes to increase calcium intake and promote adherence to osteoporosis-related medications to improve outcomes.

THERAPEUTIC GUIDELINES

THERAPEUTIC GUIDELINES

Osteoporosis is defined by BMD at the hip or spine that is less than 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the young normal mean reference population (T-score at or below –2.5). Low bone mass or osteopenia is defined as BMD between 1.0 and 2.5 SD below than that of a young normal adult (T-score between –1.0 and –2.5). The World Health Organization has established the following criteria based on BMD measurement at the spine, hip, or forearm by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) devices (Fig. 13–1).

Figure 13–1. Definition Based on BMD Measurement.

• Normal: BMD is within 1 SD of a “young normal” adult (T-score at –1.0 and above).

• Low bone mass (“osteopenia”): BMD is between 1.0 and 2.5 SD below than that of a “young normal” adult (T-score between –1.0 and –2.5).

• Osteoporosis: BMD is 2.5 SD or more below than that of a “young normal” adult (T-score at or below –2.5). Patients in this group who have already experienced one or more fractures are deemed to have severe or “established” osteoporosis.

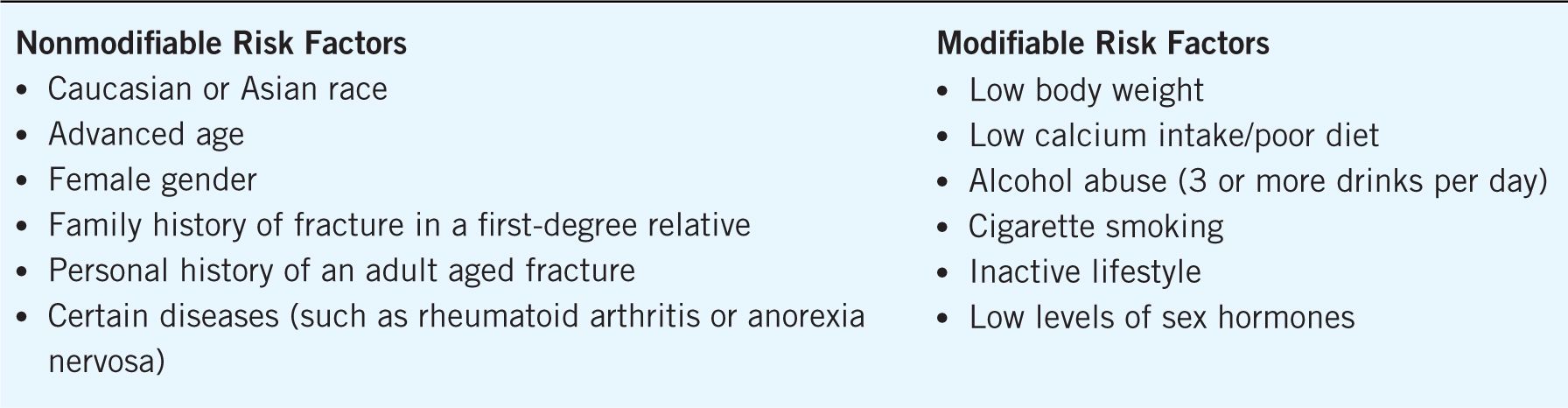

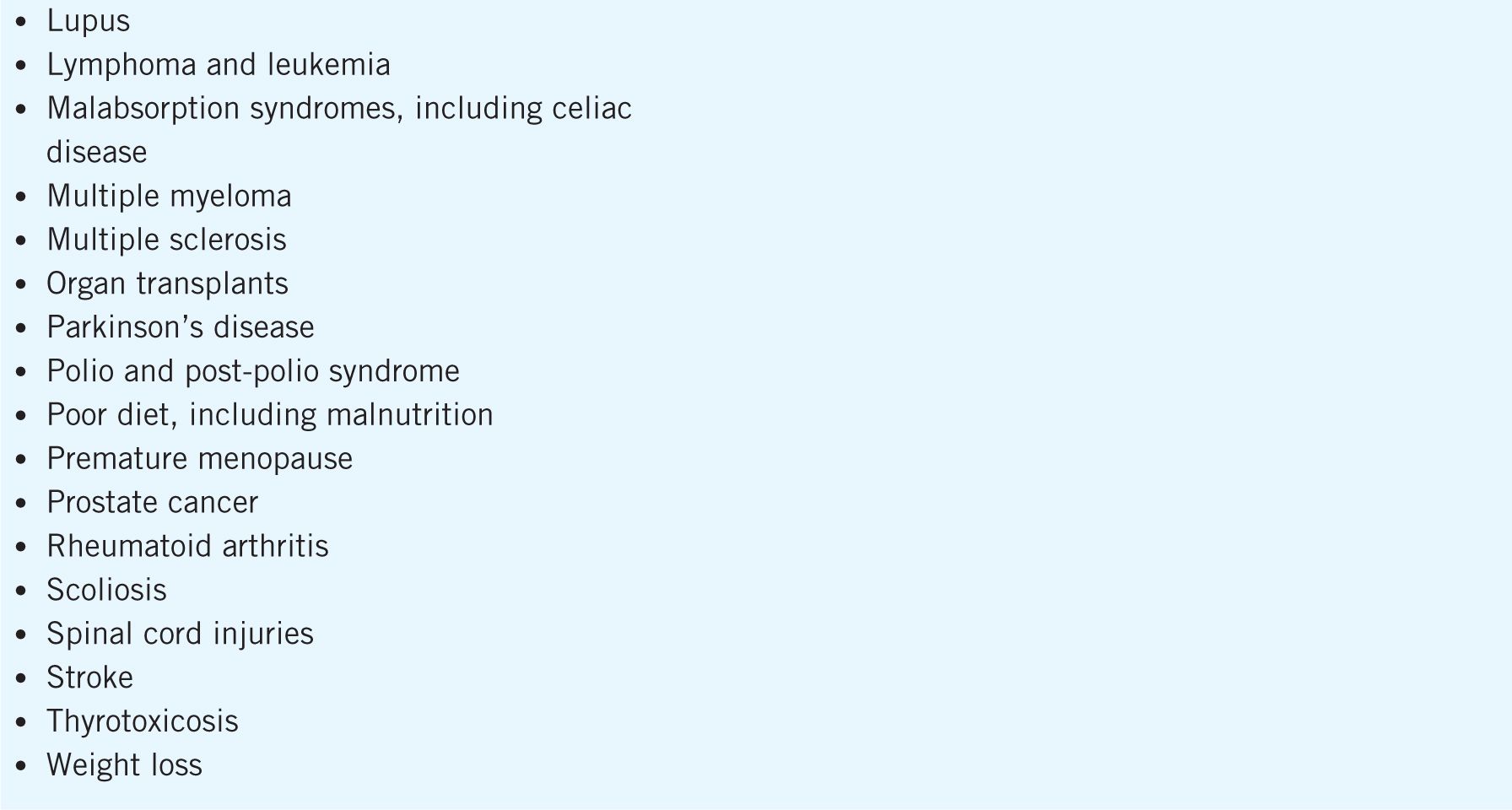

All postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age should be assessed for osteoporosis risk.1 In addition to the modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors, a number of medical conditions, disease states, and medications have been associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis. Some of the conditions and diseases that may cause bone loss and medications that contribute to an increased osteoporosis and fracture risk are detailed in Table 13–2.

Table 13–2. Medical Conditions, Disease States, and Medications Associated with an Increased Risk of Osteoporosis

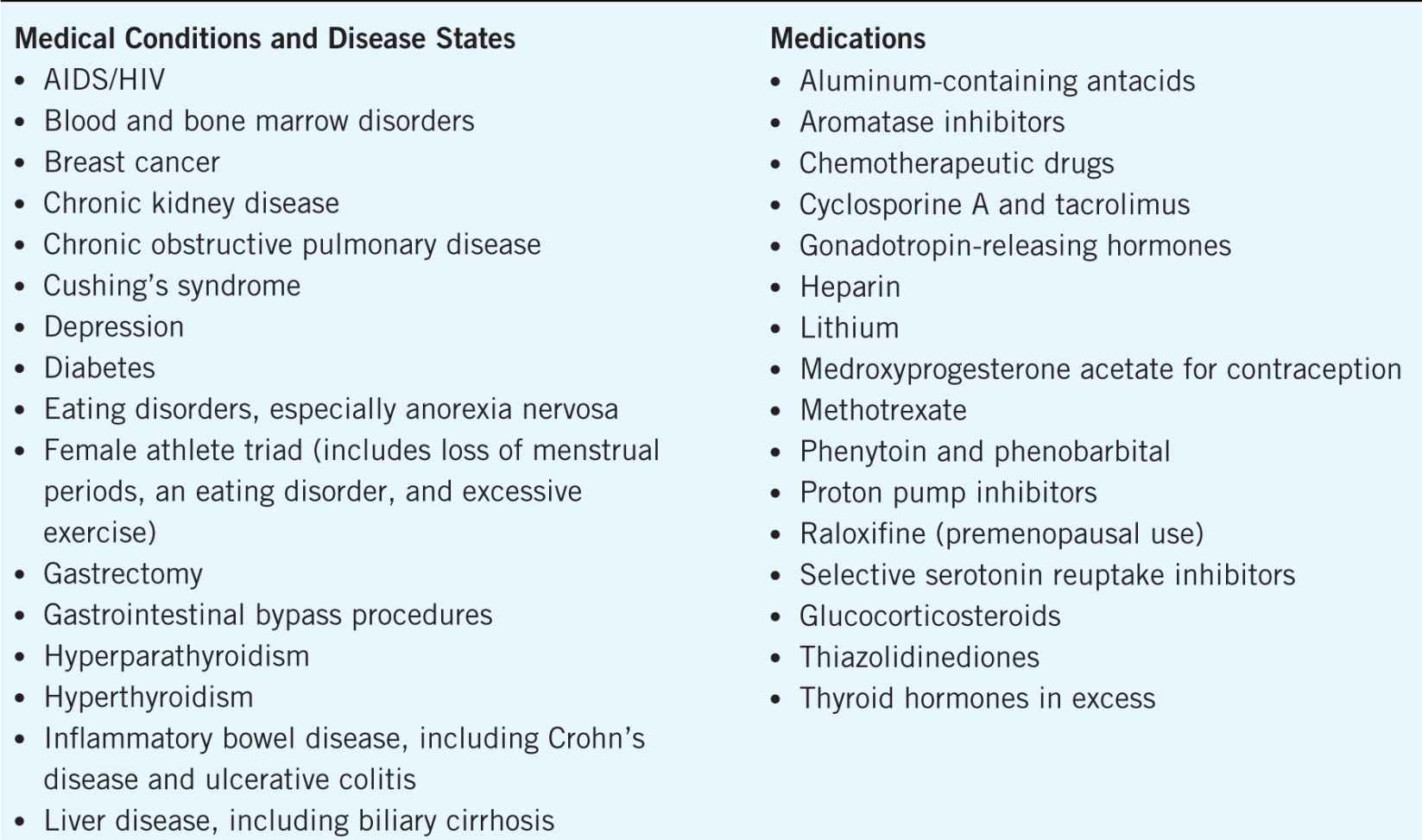

Daily intake of calcium and vitamin D is a safe way to help reduce fracture risk. Adequate calcium intake throughout the lifespan is necessary for achieving sufficient bone mass and maintenance of bone health. Vitamin D plays an integral part in calcium absorption and bone health. The calcium and vitamin D recommendations for all patients defined by the NOF are outlined in Table 13–3.1 Adults aged 50 years and older should have an intake of calcium of 1200 mg and 800–1000 international units of vitamin D every day from all sources, including food and supplements.1 Increasing dietary calcium and vitamin D is the first-line approach; however, supplements should be used when an adequate dietary intake cannot be achieved.

Table 13–3. National Osteoporosis Foundation’s Calcium and Vitamin D Recommendations

There are many calcium-rich foods including milk, yogurt, cheese, broccoli, turnip greens, soy products, tofu, and calcium-fortified foods. Dietary sources of vitamin D include vitamin D-fortified milk and cereal, egg yolks, saltwater fish, and liver. Selected examples of approximate calcium amounts in food sources are:

Dairy foods

Yogurt (1 cup)—350 mg

Milk (1 cup)—300 mg

Cheddar cheese (1 oz.)—200 mg

Part-skim ricotta cheese (¼ cup)—170 mg

Cottage cheese (1 cup)—150 mg

Nondairy foods

Black beans (1 cup)—100 mg

Broccoli (1 cup, cooked)—150 mg

Orange juice, calcium-fortified (6 oz.)—350 mg

Turnip greens, cooked (½ cup)—100 mg

Pink salmon with bones, cooked (3 oz.)—180 mg

Soy products

Soy milk, calcium-enriched (1 cup)—300 mg

Soy yogurt, calcium-enriched (¾ cup)—300 mg

Tofu, firm or extra firm (¼ cup)—250 mg

Calcium is available in several OTC supplement products including calcium carbonate (40% elemental calcium) and calcium citrate (21% elemental calcium). Calcium phosphate, calcium lactate, and calcium gluconate are not recommended for calcium supplementation because they have small amounts of elemental calcium. Calcium carbonate is the least expensive and has more elemental calcium; however, it must be taken with meals and needs an acidic environment for absorption. Calcium citrate is more expensive, but it is more easily absorbed and does not require an acidic environment for absorption. In addition, the frequency of the side effects of gas and constipation is more common with calcium carbonate than with calcium citrate. Patient’s concomitant disease states and medications must be considered when making a calcium recommendation. For example, calcium carbonate products have decreased absorption with concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors; hyperthyroidism is associated with an increased excretion of calcium; fiber laxatives can decrease calcium absorption if given concurrently; alcohol intake can decrease calcium absorption.

Patients should be counseled to spread out the calcium intake from food and supplements throughout the day because no more than 500 mg of calcium can be absorbed at any one time. Since caffeine increases calcium loss in the urine, patients should limit caffeine intake to 1–2 cups of coffee or soda per day. In addition, products labeled “USP Verified” are guaranteed by the United States Pharmacopeia for identity, strength, purity, and quality and should be recommended whenever possible.

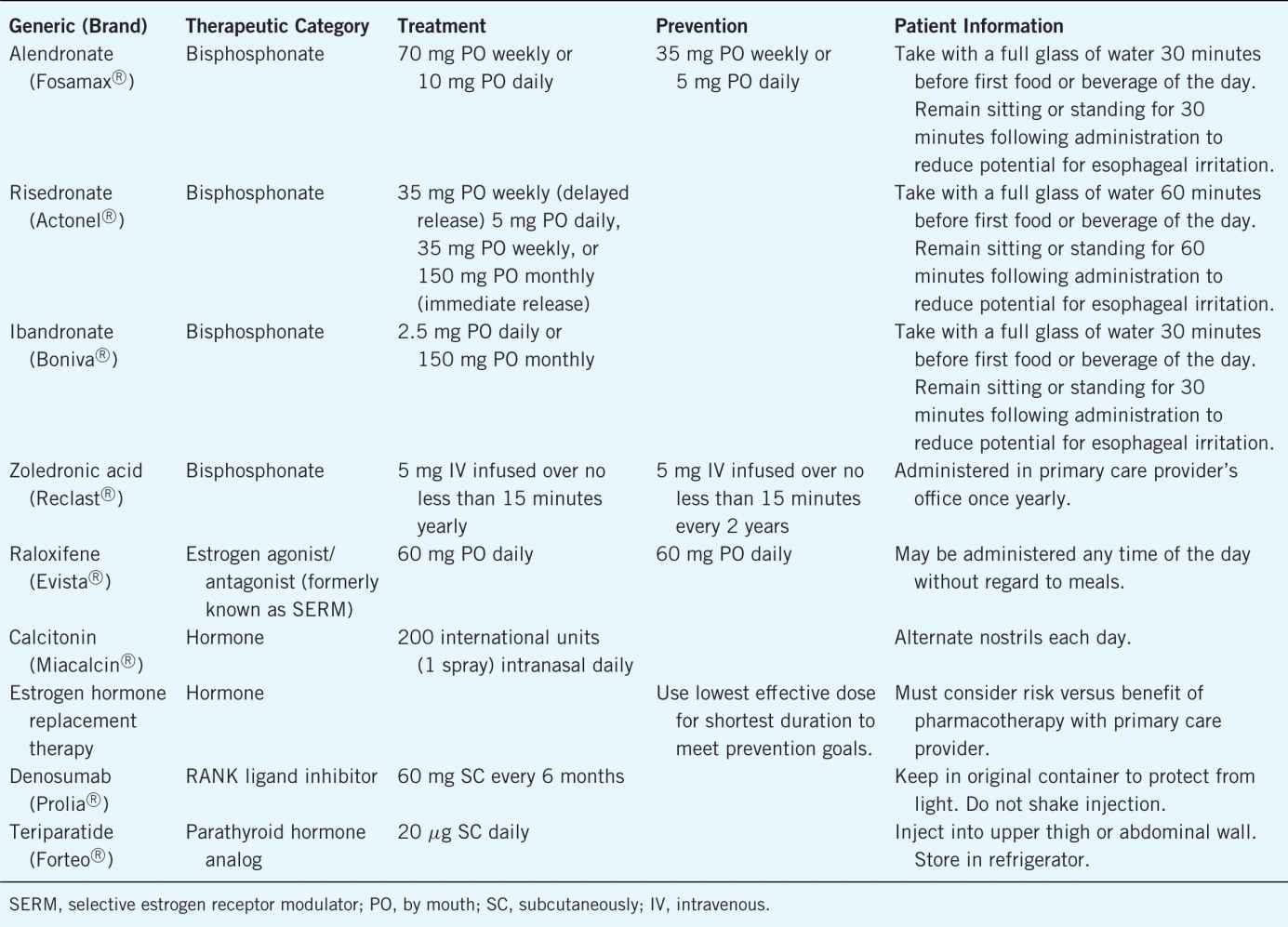

There are many medications that are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Table 13–4 provides details on each. Patient counseling regarding side effects and administration of these medications is very important. It is also essential to inquire about patient’s adherence to the osteoporosis medication to reduce fracture risk.

Table 13–4. Medications Used for Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment

BONE DENSITOMETRY DEVICES

BONE DENSITOMETRY DEVICES

Prior to establishing a community pharmacy-based BMD screening program, bone densitometry devices should be researched and compared on the basis of cost, portability, reliability, and ease of use. Pharmacists and other stakeholders should understand the scope of the selected device in the ability to provide screenings as opposed to diagnosis.1 Screenings identify persons at risk that will require additional follow-up with a primary care provider to determine an assessment of osteopenia or osteoporosis. The following groups are identified as persons of risk to identify for BMD screening/testing:

• All women 65 years of age and older

• Postmenopausal women younger than 65 if they have one or more specific risk factors:

![]() Current cigarette smoking status

Current cigarette smoking status

![]() Personal history of adult facture

Personal history of adult facture

![]() Adult fracture in a first-degree relative

Adult fracture in a first-degree relative

![]() Low body weight (< 127 lb.)

Low body weight (< 127 lb.)

• Postmenopausal women who present with factures

• Women considering therapy for osteoporosis

• Women who have been on hormone replacement therapy for prolonged periods of time

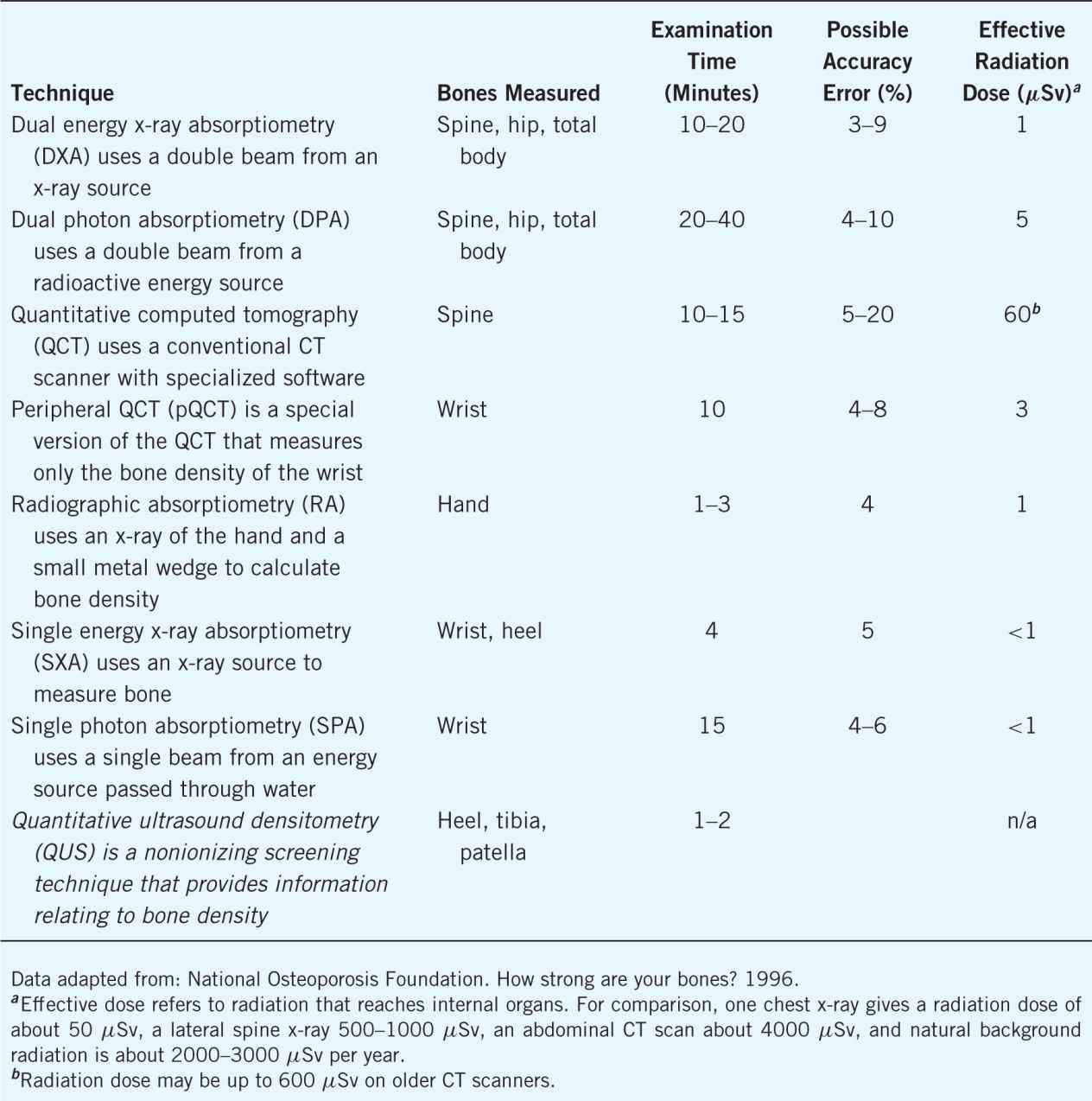

DXA is the gold standard to determine BMD, which can be either central or peripheral. Diagnosis of osteoporosis is only determined by central DXA, and screening may occur via peripheral DXA (pDXA).1 Other means of screening are single-energy x-ray absorptiometry (SXA), radiographic absorptiometry, quantitative computed tomography (QCT), and quantitative ultrasound densitometry (QUS).6 Identifying a screening device, either x-ray or ultrasound, that measures calcaneal bone (heel) will correlate with axial bone sites (hip and spine) and further determine the risk of future fracture.2 Bone density instruments may range in price from $10,000 to $30,000.2 It may not be cost-effective for pharmacies to purchase an expensive piece of equipment. However, operating costs of the screening devices are generally low and require the purchase of ultrasound gel, 70% isopropyl alcohol, and cleaning wipes. Creating a business plan will assist with determining the device necessary for completion of the osteoporosis screening services. Purchasing a device with high incidence of accuracy is necessary. Even though pharmacists are not diagnosing patients with osteoporosis, a reliable tool is needed to produce accurate results for use both by the patient and their primary care providers. Bone densitometry devices are detailed in Table 13–5.

Table 13–5. Characteristics of Techniques for Measuring Bone Density

Portability is an essential characteristic necessary for a BMD screening device. Having a mobile unit will allow pharmacists to transfer the unit from one pharmacy location to the next, conduct on-site screenings for employer groups, and partner with primary care providers in their offices. Having mobile equipment will strengthen the pharmacy and pharmacist’s return on investment of the screening program. Mobility will also assist with marketing of the newly defined BMD services.

DEVELOPING SERVICES

DEVELOPING SERVICES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree