chapter 3 Organic molecules: the chemistry of carbon and hydrogen

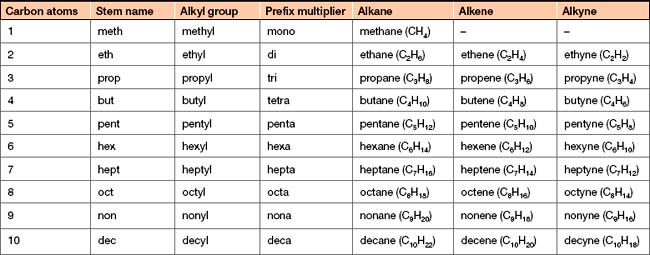

Alkanes are saturated hydrocarbons, alkenes have one or more double bonds and alkynes have one or more triple bonds.

Alkanes are saturated hydrocarbons, alkenes have one or more double bonds and alkynes have one or more triple bonds.In the early 19th century, Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius classified compounds into two categories. Those that were isolated from plants or animals were called organic, while those extracted from ores and minerals were inorganic. Later, in 1828, Friedrich Wöhler used an inorganic molecule (ammonium cyanate, NH4OCN) to synthesise urea (H2NCONH2), an organic molecule. This initiated the synthesis of organic molecules in the laboratory. Of the more than 10 million compounds that have been discovered, at least 90% are molecules that contain carbon. More than 1.5 million new molecules are discovered or synthesised each year and almost all of these are compounds of carbon. Just as there are millions of different types of living organisms on this planet, there are millions of different organic molecules, each with different chemical and physical properties.

Why is carbon such a special element?

Carbon (C) appears in the second row of the periodic table and has four bonding electrons in its valence shell. Similarly to other non-metals, carbon needs eight electrons to satisfy its valence shell. Carbon therefore forms four bonds with other atoms (each bond consisting of one of carbon’s electrons and one of the bonding atom’s electrons). Every valence electron participates in bonding, thus the bonds made by a carbon atom will be distributed evenly over the atom’s surface. These bonds form a tetrahedron as described in Chapter 1.

The chemistry of carbon is dominated by three factors:

Formulas used in organic chemistry

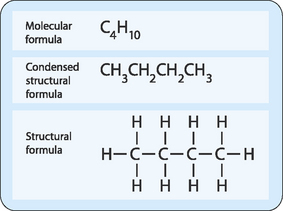

Three different types of formula are used when working with organic molecules (Fig 3-1). The simplest is referred to as the molecular formula and indicates the number of each type of atom in a molecule. However, this does not give any structural information, particularly when a large number of atoms are involved. To deal with this a condensed structural formula can be used which shows the number of hydrogen atoms bonded to each carbon atom in the molecule. The most information is shown using a structural formula which indicates how the hydrogen and carbon atoms are bonded and arranged, and uses dashes for bonds.

Hydrocarbons

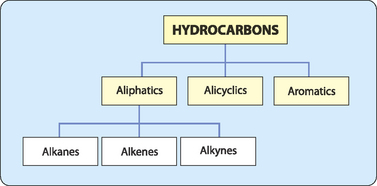

The simplest organic chemicals, called hydrocarbons, contain only carbon and hydrogen atoms (Fig 3-2). The simplest hydrocarbon (methane) contains a single carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms. Aliphatic molecules have carbons linked in an open chain (acyclic) form, one in which the carbons are arranged in a linear manner. Alicyclic molecules have carbons linked in a cyclic structure in which the first and last carbon atoms of a chain are connected to one another. Aromatic molecules contain one or more benzene rings, an extremely stable type of cyclic structure.

Aliphatic compounds

Simple hydrocarbons are non-cyclic molecules that can be classified into three groups depending on the type of carbon–carbon bonds that occur in the molecule (Table 3-1).

Alkanes burn in oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and water vapour. This means that alkanes are flammable, making them good fuels. For example, methane is the major component of natural gas, and butane is used in liquid form in lighters.

Alicyclic compounds

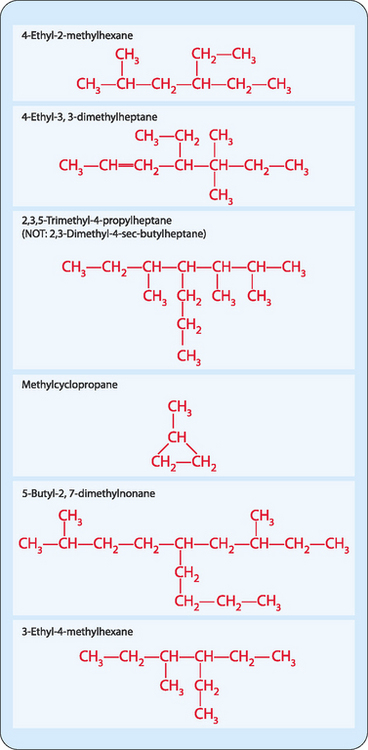

Alicyclic compounds are aliphatic cyclic compounds, with at least some of their carbons arranged in a ring. Some typical alicyclic compounds are shown in Figure 3-4. Generally the smaller rings are less stable than the larger ones. These compounds are named as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree