Chart summarizing OPTN algorithm for allocation of adult donor hearts

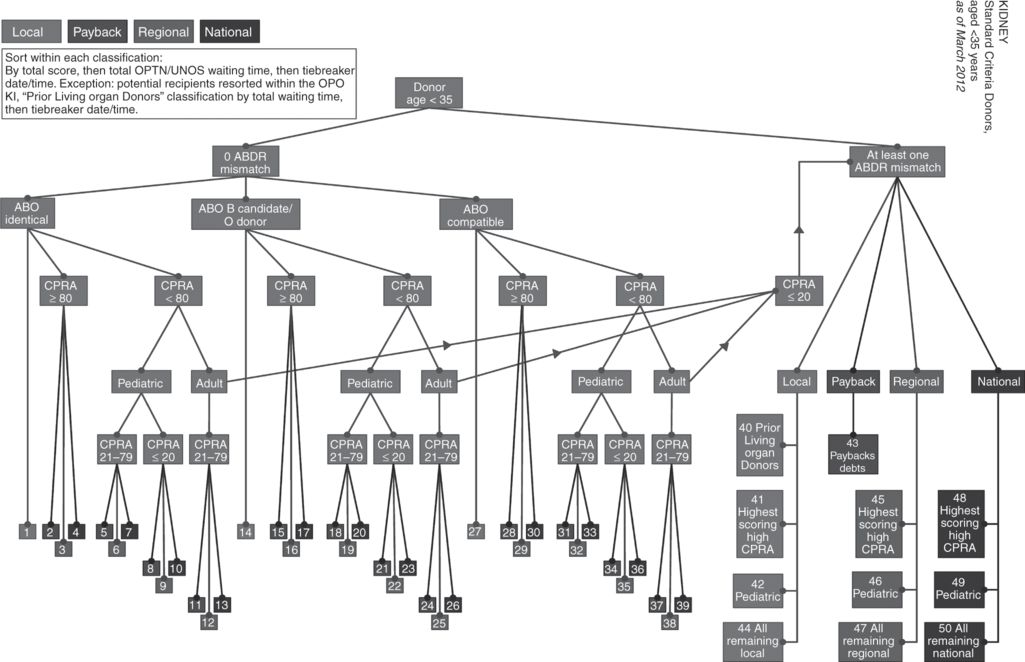

Chart summarizing OPTN algorithm for allocation of kidneys from standard criteria donors aged younger than 35 years

What moral considerations are these algorithms designed to address? According to one recent review, “the goal of deceased donor organ allocation policy in the US has been to balance utility and equity in the distribution of deceased donor organs. The policy has changed incrementally over time in efforts to optimize allocation to meet these often competing goals.”34 Because organs are scarce, and because the goals of utility and equity are “often competing,” allocation systems must “balance” these general goals, by assigning relative priorities or weights to different factors in order to arrive at a discrete ranking for each candidate for each specific organ. What exactly is meant by these general goals of utility and equity? How do specific allocation criteria serve each goal? Let’s consider each of these goals and their corresponding criteria.

Utility and its criteria. Generally speaking, utility refers to assessment of the consequences of an action. In this context, we promote utility by selecting patients for transplantation who are most likely to benefit, and least likely to be harmed, by this procedure. Notice that one can assess the utility of transplantation for an individual patient, and also for a group of patients, as, for example, the local or national waiting list for a particular organ. Transplantation may promise significant benefit for a particular patient, such as an extension of life and significant improvement in the quality of life, but even greater benefit for another patient, because the latter patient may live longer and have even more improvement in his or her quality of life. In this case, if all other factors are equal, the overall utility for a group that includes both patients is increased by allocating the organ to the latter patient. Utility-based criteria in allocation algorithms include the following:

1 blood type compatibility (because organs of an incompatible blood type are rejected)

2 negative cross-match testing (performed in kidney transplantation to determine that the potential recipient does not have pre-formed antibodies that will reject the organ)

3 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching (used in kidney and pancreas transplantation to reduce the likelihood of organ rejection when these antigens do not match)

Each of these criteria is used to rule out candidates who are unlikely to benefit and likely to be harmed by transplantation with a particular donor organ.

Equity and its criteria. Generally speaking, equity refers to the concern to provide fair access to a valued good or service. In this context, we promote equity by giving all those who need and can benefit from transplantation a fair opportunity to receive it. Unlike utility, equity is not primarily concerned with producing good individual or overall consequences of the practice of transplantation, but rather with giving patients access to transplantation based on their need, desert, or some other morally significant consideration. Equity-based criteria in organ allocation systems include the following:

1 urgency (heart, liver, and lung allocation algorithms give priority to the sickest patients, those most likely to die in the near future without a transplant)

2 waiting time (because patients waiting longer for an organ have a stronger claim than those waiting a shorter time)

3 prior living donors (because those who have given an organ to another should have priority if they later suffer organ failure, in part because of their donation)

4 degree of immune system pre-sensitization (to give certain kidney transplant candidates an increased chance for transplantation)35

Incorporating these criteria into allocation algorithms gives some patients access to transplantation despite the fact that another waiting patient is likely to benefit more from receiving that organ.

Mixed criteria. Additional organ allocation criteria can be defended using both utility and equity arguments. These “mixed” criteria include the following:

1 geographic proximity. Allocation criteria give priority to waiting patients who are closer to where the deceased donor organ was recovered. In the early days of transplantation, there was a strong utility argument for this criterion, since organs needed to be transplanted as soon as possible after their recovery in order to function properly. Better organ preservation and transportation systems now allow organs to remain viable longer, and so this utility argument is less persuasive. An equity argument can also be made for geographic proximity, namely, local community and organizational efforts to donate and recover organs should be rewarded by enabling patients in the same community or region to receive those organs.

2 age. Allocation algorithms commonly give priority to pediatric over adult patients. This priority can be defended on utility grounds, since end-stage organ failure in children can stunt growth and have other severe quality of life consequences, and children are likely to live longer than elderly organ recipients. It may also be defended on equity grounds, appealing to an argument that children deserve priority because they have not yet had the opportunities and experiences that we should strive to provide to all people as parts of a full life.

As these different criteria suggest, we recognize the moral significance of both utility and equity considerations in allocating organs, and so are unwilling to give one of these goals absolute priority over the other. We are faced, therefore, with the difficult question of how to strike an appropriate balance between these general goals, and among multiple specific allocation criteria. Which criteria should be weighted more heavily, and which less? These issues provoke ongoing debate and frequent revision of UNOS allocation algorithms. Consider, for example, the following two representative questions:

1 Should the kidney allocation system permit large differences in access to transplantation for patients of different races?36 The initial UNOS kidney allocation system put great weight on HLA antigen matching between the donor and recipient. Because most kidney donors are white, and antigens are more often shared within than across racial groupings, white patients were more likely to be ranked ahead of minority patients, and minority patients had much longer waiting times. The system was revised to de-emphasize antigen matching, giving minority patients a better chance to receive a kidney, but more antigen mismatches between donor and recipient can result in earlier rejection of the organ, reducing its overall benefit. This risk of rejection may be offset, however, by improved post-transplant immunosuppressive therapies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree